Nickolas Nickleby was Dickens’s third novel, and his first featuring a young man as the eponymous protagonist. Mr Pickwick of The Pickwick Papers (hereafter Pickwick) had been a portly middle-aged gentleman thrust into a picaresque adventure, perhaps against his better judgment. Oliver Twist was a young orphan boy who, thanks to the benevolence of Mr Brownlow and those in his sphere, was reinstated with a family and a modest fortune, like a fairy tale come true. Nicholas Nickleby, on the other hand, is nineteen years old, and is forced to consider his family’s future when his father, Godfrey, a poor business man, dies, leaving the family in financially straitened circumstances. Nicholas’s uncle, Ralph, is a successful businessman, but he has little interest in anything beyond finance, is contemptuous of his brother’s business failings and lacks empathy for his brother’s family. When he is approached for help, he suggests Nicholas apply for a low-paying job as a teacher in Dotheboys School, where orphans and unfortunate children of second marriages tend to end up at an alarming rate, and that Kate, Nicholas’s sister, should take on seamstress work. For a family of the social status of the Nicklebys, this is a terrible come-down. Nevertheless, both Nicholas and Kate accept the positions their uncle helps them acquire.

Nicholas Nickleby was published between March 1838 to September 1939 in serial form by Chapman and Hall. Its publication schedule is revealing of Dickens’s early career as a novelist. Most of the monthly issues were published in tandem with the republication of Dickens’s earlier works, now anthologised in serial form as Sketches by Boz. In addition to that, the first half of Nicholas Nickleby was published concurrently with Oliver Twist (hereafter Oliver), meaning that the first half of Nicholas Nickleby was being written as the second half of Oliver was also being produced. As a reader interested in tracing the development of Dickens as a writer, this is too tantalising to ignore. Oliver Twist had been a shorter work than Pickwick, and lacked its exuberance and humour. In fact, some of the detail of the orphanage, of the conditions of the poor in London, along with the violent ending of the novel were decidedly grim. When Dickens signed an agreement with Chapman and Hall to write Nicholas Nickleby, he agreed to produce a book “of a similar character and of the same extent and contents in point of quality” as Pickwick. In short, they wanted a commercial product that could be exploited to the same extent as Pickwick – its length – while also reviving the stylistic and comic aspects of that book. Yet that is not what Dickens did, at least according to my reading. Early in Nicholas Nickleby Dickens introduces narrative elements that are characteristic of Pickwick. For instance, during the journey back to Yorkshire where Nicholas will take up his post in Wakeford Squeers’s school, there is a coach accident, and while they await a replacement coach, a grey-haired gentleman tells the story of five maidenly sisters. The digression is a familiar element of Pickwick, and readers of Dickens’s time would have recognised the device as a familiar adaptation from his earlier work. But the device is not repeated. There is also a picaresque quality to Nicholas Nickleby that derives from Pickwick. Nicholas slips from one situation to another without any preordained plan. His only imperative is that he make money to support his family. As such, he works in various positions – as a teacher, a secretary, even as a playwright and actor – before settling into his position with the philanthropic Cheeryble brothers, Charles and Ned, and their long-faithful clerk, Tim Linkinwater.

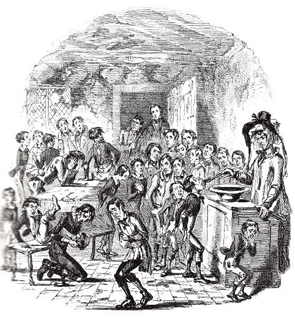

But cutting across the episodic picaresque elements is a story arc that has more in common with Oliver Twist. If Oliver is a minor character in his own story (beyond the first third of the book), in Nicholas Nickleby it is a minor character, Smikes, whose story and fate are central to much of what happens in the overarching plot. There are some broad plot outlines that seem remarkably similar to Oliver but might be overlooked when considering the minutiae of Dickens’s extraordinarily detailed fictional voice. Smikes is an orphan, like Oliver. He attends the Dotheboys School where he has been abandoned to the cruel exploitation of Wackford Squeers, the school’s proprietor, who practically starves the boys in his care, just as the boys in Oliver’s orphanage were always left hungry. Smikes, like Oliver, flees the school after an iconic scene: Oliver asks for more, while Smikes flees, following Nicholas, after Nicholas has beaten Squeers over his treatment of the boys. Like Oliver, Nicholas and Smike have a long trip by foot back to London. Here, the story seems to diverge from its predecessor. Smike’s remains in the care of the Nickleby family, but he is never a major character. At one point, he is captured by Squeers who intends to take him back to the school, much as Oliver is sought by Fagin and Bill Sikes. As an older boy with no relations (it seems) or money, Smike is a cheap source of labour for the drudge work in the school. But the bulk of the plot concerns the unfolding fortunes of Nicholas and Kate. Kate is employed by the seamstress, Mrs Mantolini, whose financial straits, caused by her husband’s gambling and prolificacy, which make Kate vulnerable to Mrs Knag, Mrs Mantolini’s former forewoman, who dislikes Kate and takes control of the business. And Nicholas, of course, finds himself in a series of different jobs, all of which he excels at. But as in Oliver Twist, lurking in the background of this plot, is the mystery as to the real identity of Smike and his relevance to the main plot. At the heart of Nicholas Nickleby is the issue of identity, once again, and of legitimacy.

There are equivalences in characters, too, between the two novels. While there is a little bit of Oliver in Nicholas and Smike, and Smike’s fate is similar to another minor character in Oliver, there are other broad comparisons to be made. Squeers exploits the boys in his care for money, much like Fagin exploits his gang of pickpockets. The Cheeryble brothers are benevolent business men whose function in the story is similar to Mr Brownlow’s in Oliver. They provide opportunity to the hero, as well as a moral counterbalance to the evil in the story, as well as the deus ex machina of the denouement. Interestingly, Bill Sikes from Oliver finds an equivalent in Nicholas’s uncle, Ralph Nickleby. Unlike Sikes, Ralph does not use physical force. Rather, his wealth and personal influence are a threat. He introduces Kate to his own society – to men like Sir Mulberry Hawk – who see Kate as a prize or toy, while Ralph sees his niece as little more than an asset who can be sold or desired. He also develops a malignant hatred for Nicholas as he becomes aware that Nicholas’s interests are working against his own: that Nicholas may have an interest in a young lady whom Ralph hopes to defraud through the suppression of a will. If Sikes is physically threatening – his beating of Nancy is horrific – Ralph is Machiavellian, even Faustian: “Is there no way to rob them of further triumph, and spurn their mercy and compassion? Is there no devil to help me?” he thinks. “Oh! If men by selling their own souls could ride rampant for a term, for how short a term would I barter mine tonight.” Dickens’s audience loved a villain, and Ralph is the main villain of this piece. Dickens’s audience, much like today, also liked to see their villain’s comeuppance, and Ralph assuredly gets his, though it falls short of the intense drama of Sikes’s end in Oliver.

Dickens was careful, for legal reasons, to avoid the suggestion of his characters’ association with real people. In the case of the Cheeryble brothers, this wasn’t a problem, since his portrayal of them was so positive. He readily states in his 1839 preface “the BROTHERS CHEERYBLE live”. He based his characters on the Manchester merchants, Daniel and William Grant, known for their charitable activities. But in the matter of Wackford Squeers, the schoolteacher who seems to be remembered disproportionately to his presence in the story, Dickens stated, “Mr Squeers is a representative of a class, and not an individual.” Be that as it may, William Shaw, a schoolmaster of the Bowes Academy in Yorkshire, seems to have been Dickens’s model for Squeers. Dickens visited his school with his illustrator Hablot Browne (known as Phiz) shortly before starting the novel. Shaw had faced legal proceedings over his neglect of the boys in his care – several of them went blind – and like Dickens’s character, Squeers, Shaw had only one eye. But I think that Dickens’s assertion that Squeers is “of a class” can be accepted. In his 1848 preface for the first cheap edition of the novel, Dickens expanded on his discussion of the Yorkshire schools, as they were known, run by poorly qualified and morally questionable men who contributed little to the education of their students. When Mr Snawley, another minor character with an important part in the plot, brings his step-son to enrol in Squeers’s school, it becomes clear that the boy is there to be gotten rid of, as he is an impediment to Snawley’s new marriage. Squeers, himself, reveals that many of the boys in the school are “natural children”: that is, born out of wedlock and dumped in the school as a means to avoid family embarrassment. In this way, Nicholas Nickleby is more of a piece with Oliver than Pickwick, because it is in these two novels that Dickens’s social voice is developing. In Oliver we witness the slow degradation of Mr Bumble from the mock-heroic heights Dickens assigns him early in the piece, to become the resident of a workhouse, himself. In Nicholas Nickleby we anticipate the same kind of fall from grace for Mr Squeers and his horrible family.

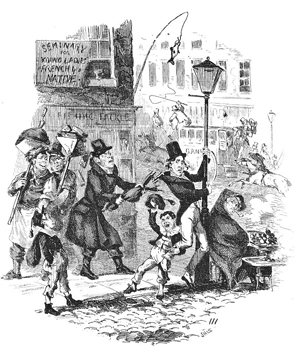

Nevertheless, the story has many more comic episodes than Oliver that alleviate the darker aspects of the story. Some are more endearing to the modern reader than others. Mrs Nickleby’s verbal peregrinations, for instance, read like a stream of consciousness, and are funny because she so often misunderstands the point, or has forgotten her own. When a mad neighbour begins to throw cucumbers over her fence (a phallic offering to be sure) she does not miss the sexual innuendo. But when the neighbour is found stuck in the chimney, singing the praises of another woman, Mrs Nickleby simply cannot get her head around the fact that she has misunderstood the target of his intentions. And Dickens is happy to take a poke at others who exploit his work, too. Apart from advertisements he released prior to the novel’s publication, warning pirates that he would “hang them on gibbets”, Nicholas’ digression into the world of theatre seems aimed at this very issue. Productions of Oliver and Nicholas Nickleby were underway before either book had completed its serialisation. Dickens takes a swipe at this practice in Nicholas Nickleby. Nicholas, himself, becomes complicit to a degree. He is employed by Mr Crummles to produce a play by the following Monday. He is given a French play and told, “There, just turn that into English, and put your name on the title-page.” Mr Curdles, who considers himself an authority on Shakespeare, believes any one of Shakespeare’s plays could be changed in their meaning simply by changing the punctuation. But I felt that this narrative digression was somewhat self-indulgent. Dickens had had aspirations for a career on the stage, and it is in this section that Nicholas seems most like the young Dickens. Oliver is the Dickens of the workhouse, pasting labels onto bottles for ten hours a day while his father languished in debtors’ prison. Nicholas is Dickens, the young man, full of energy and ambition, able to stand up for himself and right wrongs on his own behalf.

Nicholas Nickleby integrates the various elements of its plot more successfully that Oliver. The second part of Oliver has little happening, and this seems to put the book into a holding pattern before the climactic drama that centres around the question of Oliver’s identity (where the action has little to do with him) in the third part of the book. The book’s digressive love story has little weight in the plot, and Oliver’s new life detracts in the middle section from the overall dramatic impact. Nicholas Nickleby also has lulls, although the digressions are more engaging. Nicholas’ time in the theatre could be cut from the story, but the story remains interesting, all the same. The infant phenomenon – Ninetta Crummles, the 10 year old daughter of Vincent Crummles – is a wonderful invention, along with her father’s blindness to the fact that she is just not that good. There’s also a great scene in which a London manager comes to see their performance, and the actors are so distracted that they all stare at him throughout, even the corpse, played by Mr Crummles, who glances at the manager while he is being carried off-stage, to make sure he has been seen.

The love stories in Nicholas Nickleby are more successfully woven into the plot, too. Kate is made the victim of Ralph’s conniving, to impose Sir Mulberry upon her, and this helps establish Ralph’s growing antipathy towards Nicholas. Nicholas’s relationship with Madeline Bray is threatened by his own loyal promises to the Cheerybles, and further, by his uncle’s scheme to disinherit her.

Beyond the overtures of love, there is Newman Noggs, a former gentleman now fallen on hard times, whose service to Ralph and his loyalty to the rest of the family not only ties elements of the plot together, but serves as a subplot to the main story of the Nickleby family’s falling on hard times and their long road back to their former social status.

Nevertheless, I don’t think Nicholas Nickleby is as accomplished as some of Dickens’s later work. Nicholas is a fairly simple character. He is loyal, acts morally, but is prone to youthful – even violent – outbursts, like his beating of Squeers or his threatening challenge to Sir Mulberry. And Ralph is a villain, but he is not as compelling as Bill Sikes. Sikes has a visceral appeal which is lost in Ralph’s Machiavellian plotting. Sikes is driven by desire, emotion and poverty, whereas Ralph’s motivations lie in greed and contempt. Ralph strikes in slow degrees while Sikes bursts like thunder. Nicholas Nickleby isn’t as consistently good as some of Dickens’s later works, but its parts are consistently good. In Nicholas, you get a sense that this is Dickens’s first eponymous character capable of taking up the fight against injustice on his own behalf. Rather than looking back to Pickwick, Nicholas Nickleby anticipates the social novels that would define Dickens’s career.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!