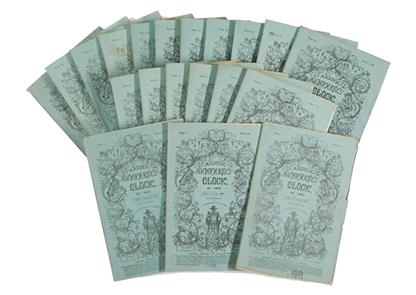

Many who profess a love of Dickens’s most popular novels may not have heard of Master Humphrey’s Clock. It’s now a literary curiosity from the nineteenth century you will probably have to track down online if you’re interested, because it’s unlikely you will stumble across it serendipitously in a bookstore. You can download a copy of Master Humphrey’s Clock for free from Project Gutenberg. In its modern form – I read the Dover Thrift Edition shown on the left – Master Humphrey’s Clock is just over a hundred pages. By ‘modern form’ I mean two things. First, that it is now published as a single volume when it was originally published as a weekly periodical. Second, the bulk of the original periodical publication has now been excised in modern versions because Dickens published two novels, The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge, as part of the magazine, and they are now published as separate novels.

Master Humphrey’s Clock is not a novel. Excluding the two novels that were originally published in it, it provided a meta-textual story that introduced the articles and stories Dickens hoped would comprise the contents of the periodical. Like his other works it was eventually published as a book in 1840, or three volumes, which included the two novels that appeared in the periodical along with short stories and other miscellanea in the order they originally appeared in the periodical. Initially, the periodical had been intended as a vehicle to publish the work of other writers, with Dickens contributing to it occasionally. Dickens was to receive £50 for each issue plus a share of half the profits, potentially netting him £5000 a year, since the distribution of the periodical was to include Europe and America, making the magazine’s success of importance to him. However, no other writers contributed to the periodical and Dickens was forced to contribute all the material, leaving him with a tight weekly deadline that was worse than the monthly deadlines he faced for his previous novels.

After initial sales dropped, Dickens’s novel, The Old Curiosity Shop helped to make the magazine successful. It is commonly believed that Dickens developed The Old Curiosity Shop from a short story in order to save Master Humphrey’s Clock. The novel was a great success, even if it is less well-regarded now. But readers did not like the second novel, Barnaby Rudge, and Dickens decided to end the run of his magazine in December 1841, about twenty months after it began in the April of the previous year, once Barnaby Rudge was complete.

So, in its ‘modern form’, Master Humphrey’s Clock is what is left from Dickens’s periodical after the two novels that were published as part of it are removed.

This is not to say that what is left is a heterogeneous jumble of leftovers. In fact, I would argue, that what Dickens produced as a meta-narrative, is worthy of being read on its own; that it is even a rewarding read. A caveat to be placed on that judgment lies, of course, with the tastes of the reader and any potential interest one might have for the subject matter. Master Humphrey’s Clock, as it now appears to us, is an uneven work. It comprises several short stories, some letters, as well as an on-going narrative about the literary club that Master Humphrey has inaugurated. The premise is that Master Humphrey is visited by a small group of friends and they take turns reading their manuscripts to each other: “One night in every week, as the clock strikes ten, we meet. At the second stroke of two, I am alone.” Master Humphrey is joined by an unnamed deaf man, by Jack Redburn who has performed a wide range of jobs for him for the past eight years, and Owen Miles, a former merchant. Master Humphrey keeps manuscripts in the clock-case by the chimney corner – “piles of dusty papers constantly placed there by our hands” – which are imbued with anticipatory enthusiasm by the random nature that stories may be drawn out, and the simple rituals of the club. Of course, what is read out by members at the gatherings are the short stories throughout the work, along with the two novels which are now removed from it.

A difficulty some readers might face with this text may lie with the relationship Dickens attempts to establish through Master Humphrey with his readers. Early in the piece we are told that while the meetings of Master Humphrey’s group only need four chairs, “there are six old chairs, and we have decided that the two empty seats shall always be placed at our table when we meet, to remind us that we may yet increase our number, if we should find two men to our mind.” I don’t think it is too much a stretch to imagine that Dickens intended his readers would gain a vicarious pleasure from the idea of these seats: that they had entered upon the company of Humphrey and his friends and through the text they were imaginatively placed within the meetings. This is to say that Dickens’s periodical was intended to engage readers with the notion of Humphrey’s club and his life, which he tells us a great deal about. Modern readers may find the idea of the club quaint and the ambitions of its members, particularly Master Humphrey, himself, somewhat exaggerated. Humphrey records that he has written into his will, “that when we are all dead the house shall be shut up, and the vacant chairs still left in their accustomed places.” It is as though Master Humphrey anticipates the legacy of these modest meetings; that his house may become a kind of shrine to their memory.

Dickens, himself, may have initially misjudged the appeal of his project. In his preface to the first volume he states (speaking in third person) that his intention had been to awaken “some of his own emotion in the bosom of his readers.” It is reasonable, then, to suppose that part of the success of the project lay with the extent to which Dickens emotionally engaged with his audience. Dickens’s characterisation of Master Humphrey is relevant here. Master Humphrey relates the abuse he suffered from suspicious and somewhat paranoid neighbours when he first moved into his house: “Various rumours were circulated to my prejudice. I was a spy, an infidel, a conjurer, a kidnapper of children, a refugee, a priest, a monster.” The epithets cover the whole gamut of parochial prejudice at the time. Over time, however, the abusers at least acknowledge his identity by using his name (“Ugly Humphrey”), until he is eventually addressed with respect (“Mr. Humphrey”), then respect becomes affection (“Old Mr. Humphrey”) and then finally, “I settled down into plain Master Humphrey”. That peculiar declension is obviously at odds with Humphrey’s advancing age; the title ‘Master’ is normally reserved for boys. And the fact is that while Master Humphrey may describe himself as “a misshapen, deformed old man”, we understand that his social isolation has been shaped by the early death of his mother and the deformity of his leg which has left him with a limited society from an early age. In short, Master Humphrey may be an old man, but his title and the impact of his early life has rendered him a somewhat childlike and naïve figure, much like other protagonists in his previous novels: Nell and Barnaby from the two novels published in this periodical, as well as earlier characters like Oliver Twist, and Smike from Nicholas Nickleby, all of whom are vulnerable innocents. What is even more peculiar is Master Humphrey’s relationship with the clock itself. He tells us that “I have all my life been attached to the inanimate objects that people my chamber”. Master Humphrey’s clock is a link to his childhood: “It is associated with my earliest recollections. It stood upon the staircase at home […] nigh sixty years ago.” For Master Humphrey, the clock is not just an object, but an emotional link to his childhood: “I incline to it as if it were alive, and could understand and give back the love I bear it.” And it seems to stand in place of his long-missing mother: “the old clock was still a faithful watcher at my chamber door.”

All this seems to go beyond the needs of a simple meta-narrative. After all, all Dickens needed to do was print the stories he had, but his strategy seems to have been both to tie his audience emotionally to his periodical, as well as to articulate an understanding of the function of his fiction. Just as the clock acts both as an emotional link to Master Humphrey’s childhood and a kind of magical conduit from which the stories emerge, the small group that gathers once a week in his chamber is also a variation of the small group of friends Master Humphrey’s mother helped him cultivate as a child. By extension, Master Humphrey’s group is a retreat from the world and its cares. Humphrey expresses a desire to “ramble through the world in a pleasant dream, rather than ever waken again to its harsh realities.” And in what reads like a manifesto, he also expresses a desire to return to the haven of childhood and its imaginative possibilities:

We are alchemists who would extract the essence of perpetual youth from dust and ashes, tempt coy Truth in many light and airy forms from the bottom of her well, and discover one crumb of comfort or one grain of good in the commonest and least-regarded matter that passes through our crucible. Spirits of past times, creatures of imagination, and people of to-day are alike the objects of our seeking, and, unlike the objects of search with most philosophers, we can insure their coming at our command.

This may have served Dickens’s own needs specifically, rather than the desires of his audience in general. There is evidence that Dickens understood this incongruence from his 1840 preface to the work:

Imagining Master Humphrey in his chimney corner, resuming night after night the narrative […] and how all these gentle spirits would trace some faint reflexion in their past lives in the varying currents of the tale – he [Dickens] has insensibly fallen into the belief that they are present to his readers as they are to him, and has forgotten that, like one whose vision is disordered, he may be conjuring up bright figures when there is nothing but empty space.

It is a sentiment expressed by Master Humphrey himself as he introduces the clock to his reader:

Lest, however, I should grow prolix in the outset by lingering too long upon our little association, confounding the enthusiasm with which I regard this chief happiness of my life with that minor degree of interest which those to whom I address myself may be supposed to feel for it, I have deemed it expedient to break off as they have seen.

Each of the stories in Master Humphrey’s Clock are introduced either by Master Humphrey or another of his group as manuscripts from which they read. The stories are then presented as separate, titled works. The first story, ‘The Giant Chronicles’, is from the pen of the deaf man and features a supernatural occurrence popular with Dickens audience: two statues come to life. Like Master Humphrey’s group, they also have an agreement to entertain each other with stories, and Magog tells Mog the story of a jealous young man driven to murder over the love of a woman. The second story, ‘A Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second’ tells the story of a jealous brother who is given custody of his brother’s son when his brother dies. He then plots to murder the child. It’s this storytelling aspect of Master Humphrey’s Clock that explains the first person narrative of the ‘single gentleman’ in The Old Curiosity Shop, a pretence which is abandoned at the end of chapter three: “I shall for the convenience of the narrative detach myself from its further course, and leave those who have prominent and necessary parts in it to speak for themselves.” After the novel is complete, Master Humphrey reveals to his companions that the ‘single gentleman’ in the story was, in fact, himself.

These layered narratives and meta-textual frames were clearly meant to be engaging for Dickens’s audience, by exploiting the relationships between the different elements of the periodical and associations with Dickens’s other works. This is most evident with Dickens’s introduction of Mr Pickwick and his servant, Sam Weller, along with Sam’s father Tony, from The Pickwick Papers, about halfway through the modern version of the work. Naturally, the intrusion of Pickwick and his companions into Master Humphrey’s metanarrative was meant to be an exciting surprise for Dickens’s readers. The Pickwick Papers had been an enormous success and established Dickens’s literary career. We first sense the anticipation of Mr Pickwick’s entry into the narrative when Master Humphrey’ sees his barber at the end of the walk with a “hasty step that betokened something remarkable”. This is followed by the initial disappointment that it is only a gentleman visitor who wishes to speak to Master Humphrey. But then we see Pickwick approach, or bits of him at least – “his hat in his hand, the sun shining on his bald head, his bland face, his bright spectacles, his fawn-coloured tights, and his black gaiters”, until it is finally revealed that this momentous visitation is made by none other than Mr Pickwick. “You knew me directly!” Pickwick is pleased to observe, taking pleasure in his own notoriety, and rounding Master Humphrey’s (and presumably the reader’s) expectations with “Now what do you think I have come for?” Of course, Pickwick has come to join Master Humphrey’s literary group, thereby gracing it with the presence of a superstar. Yet the introduction of Pickwick into the story is somewhat awkward, especially for modern audiences used to the sad recycling of fading stars through second-rate commercial vehicles. Pickwick’s appearance is followed by a no-less-awkward role reversal, as he examines and fawns over Master Humphrey’s clock, as though it was an inanimate celebrity that will never mind the intrusion into its working parts: “he set himself to consider it in every possible direction, now mounting a chair to look at the top, now going down upon his knees to examine the bottom, now surveying the sides with his spectacles almost touching the case, and now trying to peep between it and the wall to get a slight view of the back.” Pickwick’s veneration is somewhat stilted in the telling of it – somewhat hard to credit – that his introduction feels manipulative of the reader rather than generating the excitement it is meant to. It is a relief to enter Pickwick’s story, then, which begins with a tale about witches during the reign of James I and ends with an unusual burial for a convicted felon.

I found the second half of the work, after Pickwick’s appearance, to be less engaging than the first, despite what clearly must have been Dickens’s intention in introducing his popular characters. Much of the appeal of the second half will depend upon a reader’s engagement with Dickens’s characters from The Pickwick Papers. Old Tony Weller has nothing new to say. He still rails against widows as though every widow or unmarried woman might entrap him in marriage. Sam is more interesting. He begins his own literary group, Mr Weller’s Watch, with his father, with Mr Slithers, the barber and Miss Benton, the housekeeper. Their stories are in the oral tradition rather than read from manuscripts, and are more fully integrated within the narrative, as a result. Sam’s funny story of a lawyer who is given a haircut without realising as he draws up a will, or the story of a hairdresser whose shop dummies become the exemplars of romantic longings, or Tony Weller’s cautionary story he once told Sam about a boy whose character was, in reality, a distillation of Sam’s worst inclinations, reflect the working status of the group. Master Humphrey’s group meet in his chamber upstairs, while Mr Weller’s group remain in the kitchen for the duration, reflecting the social distinctions in English society. The social differences between the groups Mr Weller’s Watch and Master Humphrey’s Clock remain distinct, but Mr Weller’s group are allowed into Master Humphrey’s chamber to hear the beginning of Barnaby Rudge.

Despite some weaknesses, Master Humphrey’s Clock is also a testament to Dickens’s skill as a writer. It may be difficult for modern audiences to care about Master Humphrey’s pretensions to establish a literary society, or the celebrity aspects that Dickens introduced into the narrative with Mr Pickwick and the Wellers, yet Master Humphrey is nevertheless an affecting character. He is a vulnerable human being whose frailty is recognisable and his need for company and esteem understandable. Dickens’s desire to “awaken some of his own emotion in the bosom of his readers” reminds us that Dickens consciously pulled at the heart strings of his audience, but I didn’t feel that manipulation overtly with Master Humphrey’s death in the way that it can be felt with the death of Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop. The language Dickens uses for Nell’s death is highly emotive and steeped in Christian language and sentiments, which was appealing for Dickens’s audience, but may not be as relatable to modern readers. Little Nell’s death, as Dickens wrote it, made her an exemplar of Christian principles, of purity and innocence; an inspiration and example to inspire good deeds from others into the future. Master Humphrey’s death is more relatable. We understand the limitations of his life and his last thoughts are not religious, but of his imaginative world that has made his life bearable. Despite some flaws in Master Humphrey’s Clock, Dickens’s vision of the imaginary world of the mind and its power to give comfort and purpose at the point of Master Humphrey’s death is one of the most powerful aspects of the work. For me, it saved the second half of the work from the overpowering intrusion of his other literary characters.

So, while Master Humphrey’s Clock is not the best that you can read from Dickens, it is worth reading for a few reasons if you are of the mind to enjoy it. It provides a curious adjunct to two of his early novels, it features some of his short fiction which is worth reading, it gives us an insight into Dickens’s attitude to fiction, and it provides us with a skilful characterisation of his titular character. Others may also enjoy the appearance of Mr Pickwick and his companions. It is certainly interesting to see what Dickens did with his old characters, even if their appearance is somewhat jarring in his established narrative. But you need not read The Pickwick Papers or even The Old Curiosity Shop or Barnaby Rudge to enjoy something from this small book. It is enough when starting just knowing they exist. And given the book’s brevity, it may even be a good place to start before moving on to Dickens’s much longer novels.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!