The story of the orphan boy who asks for more is so well known that, even if you haven’t read Oliver Twist or seen the musical or its movie adaptation, you have at least some sense of the story. For that reason, this review will contain a few spoilers.

Oliver Twist was so popular in Dickens’s day that stage adaptations were appearing before the book had finished its serialisation, a bit like Game of Thrones ending on television before the novels are complete. A little context is of interest. Oliver Twist is considered to be Dickens’s first planned novel, although it was also originally published as a serial and aspects of the plot feel improvised. Its serialisation began February 1837 while The Pickwick Papers was still being published in monthly instalments. To understand the prolific nature of Dickens’s talent, it helps to know that about halfway through Oliver Twist’s serialisation, after The Pickwick Papers was finished, Dickens started issuing Nicholas Nickleby, which meant that for the duration of writing Oliver Twist he worked also on two other novels, besides. Added to this, his Sketches by Boz, a collection of short stories and descriptions of London life collated from pieces he had already published in newspapers and magazines since 1833, was published concurrently with Oliver Twist for much of its run. It is little wonder that Dickens so quickly made his mark on the London literary world.

Given this timeline, it is not surprising that aspects of Dickens’s earlier Sketches by Boz are apparent in Oliver Twist, both in its subject matter and themes. Dickens was only a young man, about 24 years old, as he began to publish Oliver Twist, so it is easy to imagine him drawing upon his shorter works and cobbling his plot together. The fact is, Dickens had not yet fully matured as a writer, and his skills at plotting were still developing. As a result, the blending of plot elements in Oliver Twist is not as successful as some might imagine. There are three broad aspects of the plot.

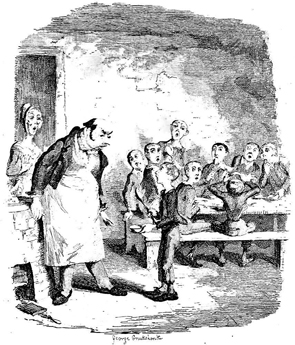

First, there is the focus on the plight of the working poor, in particular, orphans, whose future almost assuredly lay in workhouses and in poverty. Dickens was lucky not to suffer such a fate, himself, as he experienced the misery of poverty when his father was sent to Marshalsea debtors’ prison in Southwark in 1824. He was only 12 years old at the time, and worked in Warren’s Blacking Warehouse, pasting labels onto bottles for ten hours a day, only twelve years prior to his writing Oliver Twist.

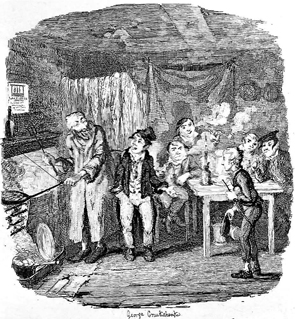

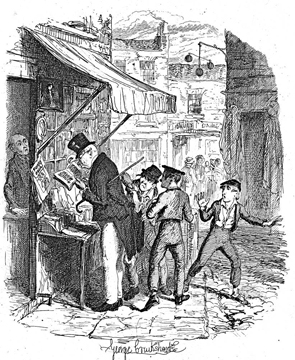

Second, is the plot involving Fagin, the Jew, Bill Sikes and Nancy, and their child minions, characterised by Jack Dawkins, otherwise known as the Artful Dodger, and Charley Bates. Fagin trains orphan children to pick pockets and the violent Sikes is at the head of the organisation.

Finally, there is the Cinderella aspect to Oliver Twist, which would seem to undermine the harsh realism of the other aspects of the plot. While Oliver is a poor orphan, an unlikely chain of events, which the narrative suggests is some kind of Providence, reunites Oliver with his rightful destiny and lifts him from his terrible circumstances.

Reading Oliver Twist after reading Sketches by Boz is like watching a writer emerge from his early germination as a court and newspaper reporter. To begin with, the story draws from descriptions of parish functionaries like the beadle in Sketches by Boz. In that work Dickens reduces the dignity of beadles with his description of candidates’ manipulative use of their families to procure votes for the position. In Oliver Twist, Mr Bumble receives Dickens’s typical treatment given to petty authoritarians. His mocking of Mr Bumble’s self-regard is worthy of Henry Fielding, and no doubt inspired by him. On the subject of Mrs Corney’s attractions, the narrator states that for Mr Bumble to succumb to her would be, “beneath the dignity of judges of the land, members of parliament, ministers of state, lord-mayors, and other great public functionaries, but more particularly beneath the stateliness and gravity of a beadle, who (as is well known) should be the sternest and most inflexible among them.” Later, Dickens will write “it would be by no means seemly in a humble author to keep so mighty a personage as a beadle waiting…” Bumble, the beadle in charge of the orphanage, is worthy of our opprobrium, and not only for his poor treatment of the children. Dickens invites his contemporary audience’s scorn when he is beaten by his wife whom he has married for questionable riches, and is finally cast into the workhouse which he formerly ran with Mrs Bumble, due to their corruption.

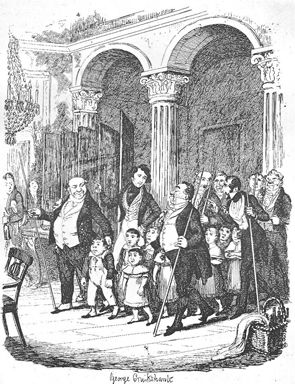

But it is Oliver’s story that has the strongest connection with the Sketches. Orphans who had no other family were the responsibility of the state and rich patrons enhanced their reputations by contributing financially to the institutions that raised them. There is a brief scene in the Sketches – ‘Public Dinners’ – in which orphans are paraded in front of rich patrons during their dinner in order to persuade the money from their wallets. There is even an illustration by Cruickshank featuring Dickens, himself, walking with the children into the event.

Another link to the Sketches is the fairy-tale element of Oliver Twist. Like Cinderella, Oliver is raised from obscurity, from poverty and despair, to a life of moderate riches, comfort and love. In the movie, Oliver!, he is apprenticed to Mr Sowerberry, the undertaker, as he is in the book, but Mr Gamfield’s attempt to acquire him as a chimney sweep, before that, is understandably omitted from the film as it is extraneous to the main flow of the narrative. But I thought that that brief episode was interesting because it provides another connection to the Sketches. I imagine that readers of Boz (Dickens began publication of Oliver Twist under his pseudonym, so readers would easily have made the connection) would have remembered the stories Dickens relates about chimney sweeps in ‘The First of May’:

A mystery hung over the sweeps in those days. Legends were in existence of wealthy gentlemen who had lost children, and who, after many years of sorrow and suffering, had found them in the character of sweeps. Stories were related of a young boy who, having been stolen from his parents in his infancy, and devoted to the occupation of chimney-sweeping, was sent, in the course of his professional career, to sweep the chimney of his mother’s bedroom; and how, being hot and tired when he came out of the chimney, he got into the bed he had so often slept in as an infant, and was discovered and recognised therein by his mother . . .

Dickens acknowledges that chimney sweeps were romanticised, even long after the realities of their situations were known to the general public. Dickens makes some recompense in Oliver Twist for this, since Oliver only escapes his apprentice because the magistrate who must ratify his indenture refuses to do so when he senses that coercion is being practised on Oliver (“the affair, in short, was becoming one of mere legal contract” Dickens observes in Sketches concerning the reality of sweeps’ indenture). Nevertheless, Oliver’s story seems inspired by that romantic tradition Dickens had already acknowledged as a fiction. And there is a sense that even Dickens understood the insubstantial fiction upon which his narrative was based. For a start, there are too many convenient coincidences that drive the plot. When Oliver is first sent out as an apprentice pickpocket with the Dodger and Charley Bates, Dodger’s plan goes wrong but it is Oliver, wholly innocent of theft, who is caught and brought before a magistrate. It would seem to strain credulity that the very man Bates and Dodger attempt to rob, Mr Brownlow, is a benevolent gentleman who takes pity on Oliver and decides to help him. Moreover, Mr Brownlow has a portrait in his house of a woman so remarkably like Oliver in looks that he begins to suspect Oliver might be the child of that woman, lost when she died in birth. Even more miraculous, is that the house Oliver is forced by Bill Sikes to enter – where he is shot as a thief and then nursed back to health – should be occupied by a young woman, Rose, who turns out in the course of the narrative to be his aunt, the sister of his own dead mother.

Apart from the coincidences upon which the novel’s narrative turns, I felt there was a degree of improvisation which is not entirely convincing, either. A large part of the problem is that Oliver’s story does not naturally have scope for the drama Dickens wishes to write. Oliver’s mother dies; he is sent to an orphanage; he is indentured to an undertaker; he escapes and walks to London; he is apprenticed as a pickpocket to Fagin; he is caught and is miraculously set on a path back to his old life. That’s nice. After that, little of dramatic interest happens to Oliver for a good portion of the second part of the book. In fact, Oliver becomes a marginal figure in the narrative for most of the rest of the book. He accompanies Rose and the Maylies to their country house for the summer, where he lives an idyllic life. Rose’s illness seems to presage another tragedy for Oliver, but it comes to nothing and it could have been cut from the story altogether.

There is a sense that Dickens is treading water in the middle of the story. Mr Bumble’s marriage to Mrs Corney is comical, as is her beating of him when he tries to assert his male ‘prerogative’. But upon reflection, the humour of it forms an uneasy adjunct to Nancy’s relationship with Sikes and her eventual fate, and it’s one of a piece with other plot developments in this section which serve to overcome the real problem in the story: that Oliver’s escape from Fagin does not justify Sikes’s and Fagin’s efforts to find him and get him back. Fagin has plenty of boys working for him and he will no doubt find others. What is so important about just one boy?

Mr Bumble’s new wife provides some much-needed exposition to alleviate this problem. And Dickens introduces further complications into the plot which strain our already encumbered sense of credulity. In the fourth chapter of the second part, alone, we are introduced to Monks, a character who is a plot device if ever there was one, whose presence suggests Fagin and Sikes’ have motive for pursuing Oliver. He also introduces mysteries surrounding Oliver that will establish some needed narrative tension for the second half of the novel: why is Oliver worth money to Fagin and Sikes?; why does Monks see Oliver as a threat?; why was Monks looking for Oliver?; why do they eventually want Oliver out of England? The answer to these questions comes in the unfolding of the plot, but it is difficult not to think that the questions are raised merely to form a strained narrative yoke between Oliver’s initial story and the latter half of the book, in which the narrative interest resides with the criminal underclass of London.

In short, having landed Oliver in his orphanage, it would not be enough to allow him to remain there, despite the reality Dickens claims for the novel in his 1841 and 1850 prefaces to the novel: the kind of reality that requires Dick, Oliver’s orphan friend, to die there with the stroke of a four-word sentence near the end of the novel. Dick is a minor figure, but a reminder that Oliver’s opportunities would, in reality, be few. But it is imperative that Fagin and Sikes’s interest in Oliver had sense made of it, and the means by which Dickens achieves this, is through the romance of fairy stories of the poor and encumbering the plot with a backstory that requires some laborious exposition late in the novel.

The fact that Oliver’s story, alone, was not enough for a novel is only one half of the issue, I think. Dickens reveals in his 1841 preface that he considered his story founded upon ‘TRUTH’, suggesting he wished to avoid the accusation of writing a ‘Newgate Novel’. Newgate novels were sensationalised fictional accounts of crime, named after the Newgate prison in London. They were considered a close cousin of what we would now call True Crime. But Dickens, to his credit, hoped to produce something more complex, at least in his characterisations, than novels like Jack Sheppard by William Ainsworth. To this end Dickens’s sub-title – ‘The Parish Boy’s Progress’ – is interesting, echoing Paul Bunyan’s title for his religious allegory, The Pilgrim’s Progress, and a hint to some of his purpose. In his 1846 preface Dickens states “It was my attempt, in my humble and far-distant sphere, to dim the false glitter surrounding something which really did exist, by showing it in its unattractive and repulsive truth”. In short, Dickens is claiming the mantle of a moralist in writing Oliver Twist. In this light, the coincidences upon which the plot turns are seen anew. Brownlow tells Monks that is was ‘a stronger hand than chance’ that set Oliver in his way. In Brownlow's mind, Oliver's fate is guided by the Providence of God. So Oliver’s tale is one of redemption, though his soul remains unblemished. Throughout, we are reminded of Oliver’s looks, which are analogous to his angelic nature. His looks make him ideal for Mr Sowerberry who wants Oliver to lead funeral processions for children. Toby Crackit recognises Oliver’s value for a life of crime, since he will be trusted by old ladies in church. And Mr Brownlow is struck by the familiarity of Oliver, and is first persuaded towards Oliver’s innocence by his looks alone.

But Oliver is an uncomplicated character who changes little, except in circumstance, throughout the novel. Which reminds me of an observation often made of Paradise Lost, that it is Milton’s Satan who his most compelling creation, rather than God, or Adam and Eve. I think that is ultimately the fate in Oliver Twist, as well: that eventually, Oliver is not as compelling to us as is Fagin, Nancy, and Bill Sikes. And while Fagin, the Jewish charlatan, replete with all manner of Jewish stereotypes (Jews have a long history of being blamed for stolen children in European tradition) it is Sikes who compels our attention and who saves this novel. By the time Oliver is reinstated to his social position at the end, I had little interest in him. It had been so long coming, and by the formula of the fairy tale, it was inevitable. But Sikes is a brutal man, and I agree with Dickens’s own assessment of Nancy’s character – she knows Sikes is violent and might kill her – that “IT IS TRUE”. Nancy and Bill Sikes represent “the best and worst shades of our common nature”, and if Nancy’s decision to help Sikes, but also help Oliver – to be afraid of Sikes but also to remain with him – seems difficult to understand, then it is also “a contradiction, an anomaly, an apparent impossibility, but it is the Truth”. Nancy’s situation is reminiscent of the wife in ‘The Hospital Patient’ from Sketches by Boz who exonerates the husband who has beaten her. Nancy’s fate is a tragedy of her good nature and the poverty that has closed opportunities to her mind.

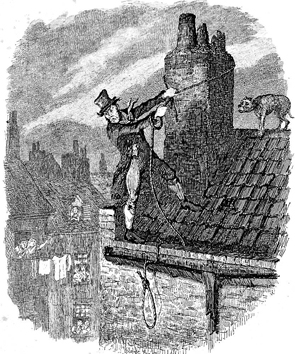

But even Sikes – especially Sikes – despicable and violent as he is, is curiously compelling. I won’t say that his wandering on the outskirts of London, haunted by Nancy’s death, and his efforts to help quell a fire, show something of his better humanity, but he is haunted, nevertheless, by his own nature and what he has done. These scenes alleviate the caricature of a monster and create a more satisfying character than is allowed Fagin, thereby bestowing on Sikes a level of complexity that makes him interesting to us. The climactic scene of Sikes on the roof, alone, is worth reading the entire book for. It is one of the tensest scenes I have read and is a great example of Dickens’s power as a writer. Sikes is not just a prisoner attempting to escape: like his dog, he is trapped on the roof, and he is equally a trapped animal, dehumanised by poverty.

Despite its flaws, this is what makes Oliver Twist a novel worthy of our attention. Notwithstanding criticisms from contemporaries like Thackeray, Dickens creates a level of sympathy for his degraded criminals that is surprising. Unlike Oliver, who is eventually given a way out of his poverty, it is characters like Nancy or little Dick who have none, or can see no way out, that concern us. I think Dickens’s second novel strains to hold its narrative elements together and to justify its plot, but individual elements in the plot – its humour, and its tragedy – are so well executed, that the book is still a compelling read.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!