The first three chapters of Martin Chuzzlewit were published in the December of 1842, and the book was serialised in monthly instalments by Chapman and Hall until its conclusion in July 1844. Martin Chuzzlewit failed to achieve the success enjoyed by previous novels like The Old Curiosity Shop or The Pickwick Papers. In fact, it only managed to garner about a third of the sales of Dickens’s previous books, and his publishers forced him to pay back money he had been advanced as a result. Compare this to a A Christmas Carol which was published a week before Christmas in 1843, right in the middle of the serialisation of Martin Chuzzlewit. The first edition was a run of 6000 copies and they sold out before Christmas of that year. Within the next year, thirteen new editions were released. A Christmas Carol appealed to Victorian sensibilities and a renewed interest in the holiday of Christmas. Dickens, it shows, had not flagged as an author. Martin Chuzzlewit simply wasn’t as popular. It didn’t have the emotional appeal of The Old Curiosity Shop and its young protagonist didn’t have the innocent appeal of an Oliver or Barnaby Rudge, or the righteous rage of Nicholas Nickleby. Added to this was the criticisms the book received for Dickens’s narrow portrayal of America and its people.

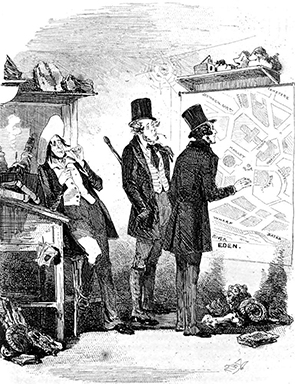

Martin Chuzzlewit is now inevitably associated with America. Dickens sends his eponymous protagonist there with his friend, Mark Tapley, to seek their fortunes in the growing towns of America’s frontier. Martin intends to make his mark as an architect by designing buildings for new settlements. Little does he know that at the very fringes of American civilisation, buildings are thrown together, valued for their practical rather than their aesthetic qualities. The promise of America is alluring and the people of America speak about themselves and their country in grandiose terms. But the reality of Eden, a fledgling town where Martin is tricked into buying land from plans, sight unseen, is that of a of a wasteland and swamp with few buildings, with inhabitants who are dying by the dozens. Martin and Mark, themselves, barely escape death from malaria in Eden, while all the children of a woman who took passage in the ship from England with Martin and Mark, die. Somewhat selfish and self-absorbed before he leaves England, Martin’s sickness and Mark’s caring for him inspire Martin to be a less selfish person, worthy of his selfless companion. Like Martin’s sudden decision to travel to America, Martin’s epiphany is barely developed in the narrative, but it does mark a turning point. Everything in Martin’s life has led him to this point. From this point on, Martin’s trajectory is on a course back to England where he hopes his sweetheart, Mary Graham, still awaits.

Dickens drew inspiration for this American interlude from his own six month journey through America, conducted between January and June of 1842. Eden, itself, was closely modelled on Cairo, a town Dickens observed as he travelled by steamboat, at the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers:

At the junction of the two rivers, on ground so flat and low and marshy, that at certain seasons of the year it is inundated to the house-tops, lies a breeding-place of fever, ague, and death; vaunted in England as a mine of Golden Hope, and speculated in, on the faith of monstrous representations, to many people’s ruin. A dismal swamp, on which the half-built houses rot away: cleared here and there for the space of a few yards; and teeming, then, with rank unwholesome vegetation, in whose baleful shade the wretched wanderers who are tempted hither, droop, and die, and lay their bones . . .

American Notes London, Penguin Books, 2004, page 190

Martin Chuzzlewit was the first novel Dickens published after his return from America, and those experiences seem to intrude upon the story with the suddenness of Martin’s decision to go. Part of this has to do with the publication history of the novel, which puts into question Dickens’s claim that this novel achieved a new cohesiveness his former novels lacked. Despite the criticisms and the book’s lacklustre sales, Dickens maintained that he thought Martin Chuzzlewit was one of the best books he wrote. He stated in his preface that, “I have endeavoured in the progress of this Tale, to resist the temptation of the current Monthly Number, and to keep a steadier eye upon the general purpose and design.” Dickens was consciously trying to deliver a more cohesive story. His earliest novel, The Pickwick Papers, had been an untidy, sprawling picaresque yarn, with various digressions; stories told by characters to other characters, that interrupted the flow of the main narrative. In writing The Pickwick Papers Dickens had been writing a serialised novel, published monthly, and had taken advantage of the medium to spin his yarn out. However, with Martin Chuzzlewit, Dickens, according to the preface of the 1850 Cheap Edition, had chosen a theme which he intended to explore: “how Selfishness propagates itself”. The means by which he chose to do this lay with the avaricious plans of members of the Chuzzlewit family to lay their hands on the Chuzzlewit fortune once old Martin, Martin’s grandfather, died. Martin’s story was to follow the course of his fall from grace – his disinheritance by his overly-suspicious grandfather – and his eventual reinstatement and triumph as his grandfather’s worthy successor.

Yet despite Dickens’s preface to Martin Chuzzlewit, it is generally thought that Dickens introduced Martin’s departure for America as a response to the novel’s poor sales, a decision which would be more in keeping with the habits of writing for a monthly audience rather than adhering to a more general overarching purpose as he claimed. There is little in the story that foreshadows Martin’s departure. John Westlock, a former student of Pecksniff’s, has just completed his five years of tuition. Mr Pecksniff maintains a reputation as a moral man, and runs a school for architecture and land surveying. But Westlock reveals that Pecksniff financially exploits his students who board in his house, and claims credit for their work when their plans are turned into commissions. Westlock says to Martin in chapter 12 (the last chapter in fifth monthly instalment of the novel) that “I feel sorry that I didn’t yield to an impulse I often had, as a boy, of running away from him [Pecksniff] and going abroad.” Martin tells Westlock, while conceding Pecksniff’s character, that he is not inclined to go abroad to seek his fortune. Instead, he naively believes he has become indispensable to Pecksniff: “I believe he looks to me to supply his defects, and couldn’t afford to lose me”. It is only when a few pages later as the chapter draws to a close, that Pecksniff (at the behest of Martin’s grandfather) impugns Martin’s character and ends his tuition, that Martin decides within a sentence, that he will go to America. It feels like a course correction in the narrative.

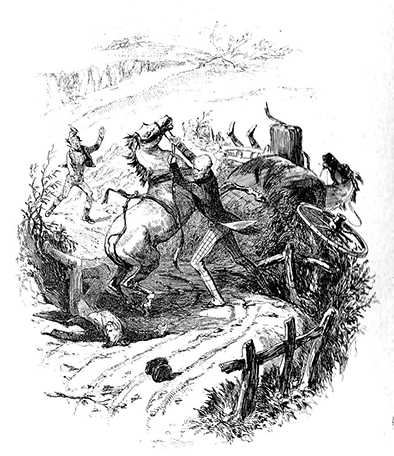

Up to this point, Martin Chuzzlewit has elements that Dickens’s contemporary audience would have found familiar. The early chapters up to the point of Martin’s expulsion recall aspects of Nicholas Nickleby, for instance. Prior to Martin’s sudden decision to emigrate, his situation is similar to Nicholas’s. Like Nicholas, Martin comes from a respectable family, but circumstances see him forced to plan a new future. For Nicholas, his father has died and lost the family money, while Martin has been disinherited by his grandfather who is suspicious of his family and their likely claims upon his wealth. Like Nicholas, Martin ends up in a school of sorts. Like Nicholas, he also leaves the school at a point of conflict. Nicholas beats Wackford Steers for his cruel treatment and exploitation of his students. Martin doesn’t beat Pecksniff before he leaves, but Dickens allows Pecksniff to fall down abjectly before Martin’s anger. He delays Pecksniff’s physical beating for later in the novel, to act as a resolution rather than as a catalyst in the plot, at the hands of the elder Martin Chuzzlewit, Martin’s grandfather.

But there are broader comparisons to be made around characterisation, too. Dickens’s most engaging characters, to modern sensibilities, tend to be his villains: Bill Sikes, Ralph Nickleby and Daniel Quilp all die grisly deaths that would have thrilled Victorians interested in the macabre, while Dickens’s innocents – Oliver Twist, Smike and little Nell – are angelic forms whose goodness is so unquestionable and their vulnerability so dire that Victorian readers were engrossed in their fates. Modern readers sometimes recoil at what feels like the author’s sentimental representations. While Dickens’s villains die horrible deaths, the deaths of Smike and little Nell are saintly and pure. In Martin Chuzzlewit, Dickens continues these sharp character delineations. There are the ‘good’ characters, Tom Pinch, Mark Tapley and Mary Graham. Tom Pinch is a former student of Pecksniff whose talents are limited, yet he is retained by Pecksniff as an assistant, and because he naively promotes Pecksniff’s school. Tom plays the organ at church for free and will hear nothing bad about his employer. Likewise, Mark Tapley who travels to America with Martin, maintains a Panglossian optimism about life. His only concern is that his life might be too easy and happy for him to be worthy of the moral credit he seeks in the eyes of others. And Mary Graham is devoted to serving old Martin Chuzzlewit, despite his curmudgeon nature and his terms, that he will pay her a wage but she will get nothing upon his death. It is the only way he will trust her intentions.

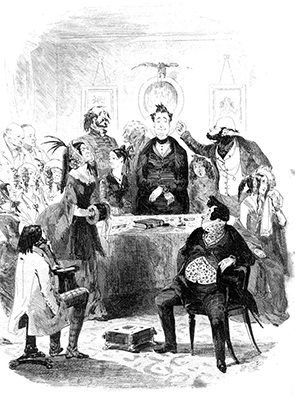

In contrast to this group is a host of other characters who represent selfishness. The representation is most graphically made by the extended Chuzzlewit family itself, who descend on the Blue Dragon, an inn run by Mrs Lupin, for the purposes of pursuing old Martin’s fortune. Old Martin has taken to travelling about to avoid his relatives, but having found him at the Blue Dragon, the family gathers for a meeting, led by the colourfully named Chevy Slyme, a nephew of old Martin, and Tigg Montague, a villain who hopes to get at the Chuzzlewit fortune by manipulating Slyme. Pecksniff is also in attendance at the meeting, since he is a cousin of old Martin. Other minor members related to old Chuzzlewit include Mr and Mrs Spottletoe and George Chuzzlewit, a bachelor cousin to old Martin. Most notable, however, is Anthony Chuzzlewit, old Martin’s brother, and his villainous son, Jonas Chuzzlewit. Tigg’s characterisation of the intentions of this grasping band is made through the metaphor of a cricket match:

The time has come when individual jealousies and interests must be forgotten for a time, sir, and union must be made against the common enemy. When the common enemy is routed, you will all set up for yourselves again; every lady and gentleman who has a part in the game, will go in on their own account and bowl away, to the best of their ability, at the testator’s wicket; and nobody will be in a worse position than before.

The ‘common enemy’ according to Tigg, is Mary, who looks after Martin. Suggestions for ‘routing’ the common enemy include poison, imprisonment, transportation and flogging. Clearly, the family is a host of villains of one shade or another. Pecksniff’s later plan to ingratiate himself with old Martin is less extreme but seems no less effective.

If Dickens’s characters can be broadly separated into two camps, Martin’s decision to immigrate to America suggests a further dichotomy in the book between England and the former colony at the expense of the Americans in the novel. However, this is not to suggest broad moral equivalences between the countries and the representations of the characters. This is not a case of England good, America bad. Dickens was certainly critical of many aspects of America in American Notes, from minor issues like his dislike of spitting, to the overfamiliarity of Americans, to more serious considerations like slavery. Dickens’s satirical treatment of America drew a lot of criticism for that. But in his 1850 preface to Martin Chuzzlewit he wrote, “I have never, in writing fiction, had any disposition to soften what is ridiculous or wrong at home, I hope (and believe) that the good-humoured people of the United States are not generally disposed to quarrel with me for carrying the same usage abroad.” The idea that Martin Chuzzlewit is Dickens’s book about America, or that America, alone, is targeted by Dickens’s satire is, as he suggests, not accurate. As a broad plan, I think the American digression helps to further Dickens’s satirical purpose. There is the personal greed and selfishness of the Chuzzlewit family which provides an entertaining story. But the American journey provides its own examples of humanity’s foibles, which, by juxtaposing the cultures of England and America, help to highlight was is “ridiculous or wrong at home.”

The opening chapter of Martin Chuzzlewit provides us with some clues as to how we might read the American section of the novel. Dickens begins with a history of the Chuzzlewit family which is really a satirical comment upon British ancestry and history. The ancestry of the Chuzzlewit family is long indeed, “descended in a direct line from Adam and Eve.” The logic of the Old Testament demands this is true, anyway. But this seemingly grandiose claim should give us pause, if we recall the story of Cain and Abel when we discover the patricide of Jonas Chuzzlewit, or if we think of Original Sin and Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the garden. Ironically, Martin returns to Eden in his American sojourn, but it is a blighted, corrupted hell. But in England, we learn, the proud lineage of history has created more comfort but is no less corruption: “the more extended the ancestry, the greater the amount of violence and vagabondism”, Dickens’s narrator explains, which was, “the healthful recreation of the Quality of this land.” The ‘Quality’, which includes the Chuzzlewit family, “were actively connected with divers slaughterous conspiracies and bloody frays.” An ancestor is said to have been involved in the Gunpowder Plot. And like many noble families, there are members who have fallen on hard times, like Diggory Chuzzlewit who is said to be “in the habit of perpetually dining with Duke Humphrey”, a euphemism meaning that he is having to miss meals. In England we find slow moral decay baked into its long history, abetted by a system of old wealth whose future recipients are at the mercy of a capricious older generation, like Martin’s grandfather, old Martin.

America is too young a country to have developed a culture of old money and an entrenched class system. The ‘Quality’ is not created from ancestry but from personal action. The first person Martin meets in America is Colonel Diver, editor of the New York Rowdy Journal. Diver tells Martin, “the organ of our aristocracy is in this city”, but it is not an aristocracy as Martin understands it. Instead, Diver explains, this ‘aristocracy’ is composed of, “intelligence and virtue. And of their necessary consequence . . . dollars.” The paper Divers runs is a rag that deals in what would today be called ‘fake news’, but Divers insists, “we got it all from the old country.”

Almost everything about America, like the settlement of Eden, itself, appears to be an illusory. Self-promotion is rife. Reputations have to be made quickly, since there is no ancestry to achieve elevation, except by the accumulation of wealth. Everyone, it seems, is “the most remarkable man in the country” for one thing or another. At dinner, the sole topic of conversation is money. And the principles upon which the country is founded sometimes seem a sham. The country is for free speech but free speech is abused by its press. The country advocates equality but keeps slaves. There is a hilarious satirical scene when Martin agrees to attend the meeting of the Watertoast Sympathisers. They have written a letter to Daniel O’Connell, who is leading resistance against the British in Ireland, to offer their support for freedom and equality. But immediately upon the mail arriving and their reading news that O’Connell is, “the advocate – consistent in it always too – of Nigger emancipation!” the letter is torn up and the funds that were to be sent to Ireland are now to be diverted to commemorate public figures who have supported the suppression, even the killing of Negroes, on the principle that “free and equal laws” must be upheld that, “render it incalculably more criminal and dangerous to teach a negro to read and write, than to roast him alive in a public city.”

But the deceptions evident in America are not unique to it. Martin is almost ruined by the deception of Zephaniah Scadder of the Eden Land Corporation who sells him wasteland in Eden. Except for the mercy of Mr Bevan, the American character who tips into the ‘good’ side of Dickens’s scale, Martin and Mark may have been stranded in America. But Dickens balances this in his English story with the deception played upon Jonas Chuzzlewit by Tigg Montague, who lures Jonas into his upstart Anglo-Bengalee Disinterested Loan and Life Assurance Company. Like the Eden Land Corporation and its map that falsely represents a burgeoning Utopian settlement, Tigg’s Assurance company lures gulls with the impressive trappings of his business premises. In reality, Tigg is only managing to pay any claims against policies with money from new policies. His business model is a sham and soon it will collapse.

What isn’t evident, so far, is that Dickens’s ‘bad’ characters really drive this plot. While Martin may be the hook that the plot hangs upon, his story is not the most compelling in the novel and he recedes into the background for a good deal of it. ‘Good’ characters and characters like Martin who strive to be better enforce the moral conclusion of the story. But characters like Tigg Montague and Jonas Chuzzlewit, especially, demand our attention. More than any other character, Jonas embodies the principles of the opening of the novel; of the potential violence of the privileged class in the protection of its interests. Like Bill Sikes and Ralph Nickleby before him, Jonas is a murderer, and the insight into the fixedness of his mind, the slow resolution to his purpose and the execution of his plan is a thrilling read. Pecksniff, in contrast, wheedles his way into old Martin’s confidence. He is reprehensible, but his grift and imposture are more akin to the deceptions found in America.

Yet Jonas’s murderous plan, and Dickens’s execution of it, narratively speaking, owe something, also, to Dickens’s contact with America. Dickens’s own writing, particularly The Pickwick Papers and Barnaby Rudge, had influenced the writing of Edgar Allen Poe (Poe’s poem, ‘The Raven’, was inspired by the raven in Barnaby Rudge). Dickens tried to get Poe’s stories published in England after he met with Poe in the March of 1842 in Philadelphia. Poe’s short story, ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ was published January 1843, the second month of the serialisation of Martin Chuzzlewit, and this time it is evident that Poe is influencing Dickens. In a climactic scene in which Jonas is haunted by the import of the murder he has committed, Dickens closely imitates the beating heart from under the floor boards in Poe’s story:

. . . lying down and burying himself once more beneath the blankets, heard his own heart beating Murder, Murder, Murder, in the bed . . . His last glance at the glass had seen a tell-tale face . . .

It is Jonas’s story that drives the interest in Martin Chuzzlewit. The beating that Pecksniff receives for his own deceptions seems like a repetition of the scene in Nicholas Nickleby and feels anticlimactic after the thrilling set piece that is Jonas’s story and comeuppance. It’s easy to feel that Jonas’s story should have been the centrepiece all along: that the digression to America was a nice piece of satire, but it doesn’t serve Dickens’s moral intention half so well as Jonas’s villainy. Dickens’s allusion to Poe’s story, as well as the tone he achieves throughout this section of the novel, somewhat in imitation of Poe’s gothic dread, shows Dickens capable of using whatever comes to hand to fashion his narrative. As a result, despite Dickens’s intention to provide a more coherent narrative, there are elements that still feel unwieldy. Mrs Gamp, for instance, an alcoholic nurse who acts as midwife and sits with the sick, proves to be as false and deceptive as Pecksniff. She is a minor character, but she was very popular with Dickens’s audience, and she remains brilliantly rendered with her own peculiar argot. Scenes like her falling out with her professional partner, Betsy Prig, are hilarious, and we should be grateful that Dickens wrote her. Yet sometimes she feels extraneous to the action.

Nevertheless, the American digression in Martin Chuzzlewit still works for me. It parallels the English story and offers a satirical viewpoint that highlights the foibles of the old country as well, rather than merely criticising America alone. Dickens believed this was one of his best novels, but I don’t think so. It still feels structurally clunky, even though Dickens balances his American and English scenes well: even though, thematically, they each complement the other. But it is still a good story that achieves a moral ending that Victorian audiences would have expected, where villainy was also involved. But it has some brilliant set pieces, particularly the murder and everything leading up to that and following it, which are both melodramatic but also gripping. Martin Chuzzlewit isn’t a perfect book, but many of its parts nearly are.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!