The Pickwick Papers was published as a serial by Chapman and Hall, between March 1836 and October 1837 for one shilling per instalment. Many books of that time were serialised rather than published complete to begin with. This left authors constantly writing ahead of the next publication date. Stephen King did this with his The Green Mile, and aspects of The Dark Tower series are evidently written in this make-it-up-as-you-go-along manner, too. Ali Smith kind of did it for her Spring Quartet, writing each of the four novels contemporaneously as events unfolded in England and the impact of Brexit was felt. But it is not common, now. The very manner of this writing and the publication cycle affects the structure of a work and leaves certain elements of the eventually-finished piece unknown even to the author as they write.

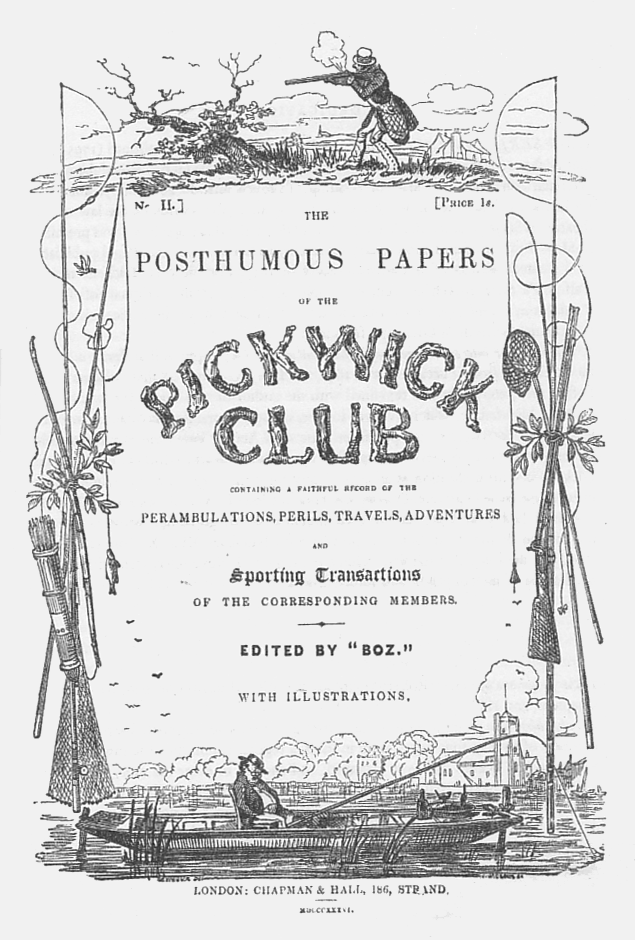

The original intention was that The Pickwick Papers would be published in twenty instalments. There were eventually nineteen publication dates, with instalments nineteen and twenty published together. The Pickwick Papers was to become Dickens’ first novel. The publishers took a risk with him, largely because of the popularity of his ‘sketches’ published under the name of ‘Boz’. Sketches by Boz was a collection of short observations of London life and stories based around English characters published in the years prior to Dickens beginning work on The Pickwick Papers. Dickens’ intention, as he began The Pickwick Papers, was to draw from this miscellaneous work to produce an entertainment in the guise of ‘found’ documents. As a result, Dickens’ name is not featured on the original title of the work. In 1847, he wrote an introduction for his amended ‘Cheap’ version of the novel, in which he explained that Boz was a contraction of ‘Boses’ (itself a mispronunciation of ‘Moses’, a nickname given to a brother). Dickens writes as Boz for his original 1836 advertisement for the work, in which he explains the ‘found’ conceit:

The Pickwick Travels, the Pickwick Diary, the Pickwick Correspondence — in short, the whole of the Pickwick Papers, were carefully preserved, and duly registered by the secretary, from time to time, in the voluminous Transactions of the Pickwick Club. These transactions have been purchased from the patriotic secretary, at an immense expense, and placed in the hands of ‘Boz’, the author of ‘Sketches Illustrative of Everyday Life, and Every Day People’ — a gentleman whom the publishers consider highly qualified for the task of arranging these important documents, and placing them before the public in an attractive form.

Advertisement from The Athenaeum, 26 March 1836

It is important to have some understanding of the publishing background of the work to appreciate why The Pickwick Papers is as it is. Because this book might seem to be something of a mess to modern readers as they embark upon the first few chapters. The opening chapter introduces us to the key characters – Samuel Pickwick (a pompous philanthropist and scientist); Tracey Tupman (middle-aged and corpulent, but always considering himself a chance with young ladies); Augustus Snodgrass (a talentless poet); and Nathaniel Winkle (an incompetent hunter) – and a chaotic meeting of the Pickwick Club, written in part as the recorded minutes for the meeting, which degenerates into a shouting match between its members. All we are left to understand, according to our narrator, is that Mr Pickwick is an estimable man (having established his reputation with a scientific tract on an obscure pond creature, the ‘Tittlebats’) and that his eponymous society will devote itself to travel, sport and adventure.

And that’s largely how The Pickwick Papers begins. In the second chapter the Pickwickians embark upon a journey which soon highlights their stated character traits and establishes the chaotic tone of the work. Pickwick quickly becomes embroiled in an argument with a cabman, suspicious of Pickwick for taking notes during their conversation. The cabman fights everyone at once after the argument escalates. It is only when a stranger (later identified as Alfred Jingle) intervenes, that the matter is resolved. Later, Tupman hears of a ball which he is eager to attend. But his friends get drunk and fall asleep. So he calls upon Jingle to accompany him. Tupman lends Jingle Winkle’s coat to that end. At the ball, Jingle insults Doctor Slammer when he cuts in on the doctor during a dance. But it is Winkle, the next morning, in a case of mistaken identity over his coat, who is challenged through a second to a duel with Slammer. Winkle’s failed attempts to maintain his dignity by hinting to Snodgrass that he should talk him out of the duel, a matter of honour, are naturally hilarious, as is much of the story at this point. And that’s just chapter two.

The story is episodic for a while, which owes much to the manner of its publication, wandering from one misadventure to the next without much consequence, interspersed with side stories which fade from the novel as Dickens eventually establishes his plot. But the fact is, this sort of farce has a short potential; without it meandering into irrelevance. It is hard to maintain without the strain of it showing in the writing. By chapter five, however, there is a sense that Dickens is beginning to move toward a purpose, when the Pickwickians, along with their as-yet-unnamed companion, Jingle, are invited to Mr Wardle’s Dingle Dell farm, where the possibilities of sexual misadventure begin to be explored in the narrative. Nevertheless, the interspersed stories and digressions continue, humorously it must be said, for some time.

I think there are other factors that affect the style of the book in its opening, apart from its mode of publication. First, Dickens was largely unknown author. Apart from his publications under the name of Boz, he had largely written for newspapers as a court reporter. As a result, his opportunity to write the book came indirectly, as an assignment working with the famous illustrator Robert Seymour. The original intention had been that Seymour would produce a series of satirical illustrations for his publishers on the subject of middle-aged sportsmen: “the members of which were to go out shooting, fishing, and so forth, and getting themselves into difficulties through their want of dexterity, would be the best means of introducing these” [Preface to the 1847 edition].

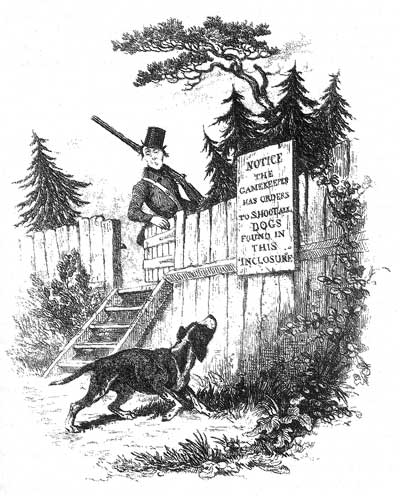

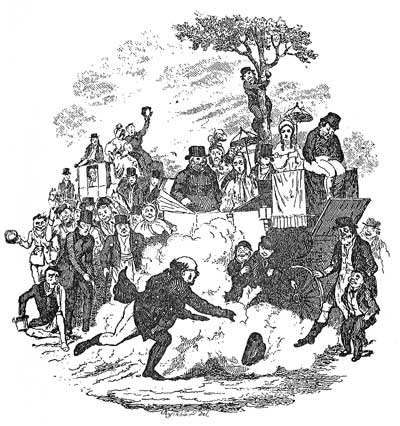

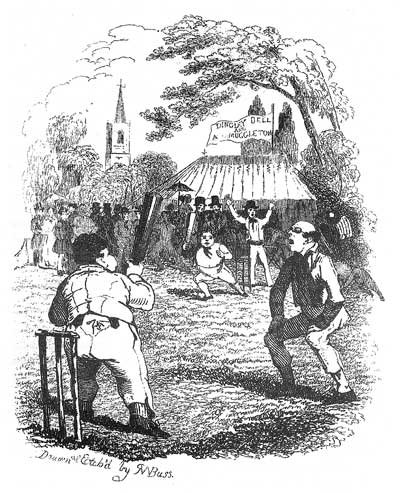

The original title page suggests the primacy of these themes. Dickens’ role was to provide humorous copy to accompany the illustrations. Dickens admitted that he had little experience of these matters and suggested, instead, “that it would be infinitely better for the plates to arise naturally from the text.” In other words, Dickens was reversing the primacy of the illustrations over text. It is easy to cite examples that conform to the original intentions of the work – of masculine pursuits – from the book’s early chapters: having been invited to watch a mock battle in the countryside, for instance, Pickwick inadvertently comes between the two ‘armies’ when he chases his hat, blown from his head, onto the field; Winkle proves himself to be an inept horseman; the Dingley Dell cricket team is soundly trounced by the All-Muggleton cricket team; Pickwick gets drunk while hunting, is found asleep and is placed in a pound by the angry landowner, and pelted with vegetables by a crowd; and the Pickwickians’ efforts to rescue Rachel Wardle, Mr Wardle’s spinster sister, from the unscrupulous intention of Jingle to elope with her, meets only with disaster. But the fact remains, that Dickens’ writing project had consumed the original creative intention of the work, that Seymour’s illustrations were the centre piece. Seymour blew his brains out two days after first meeting Dickens, when Dickens’ complained about the quality of one of Seymour’s illustrations. In his 1867 preface, Dickens defended himself against claims by Seymour’s widow that her husband had been a creative force behind the book, itself. Dickens asserted, “That, MR SEYMOUR never originated or suggested an incident, a phrase, or a word, to be found in this book”, and it would seem in character for a man later known for his portrayal of lawyer, that he offered the witness of two people to his meeting with Seymour and other written testimony as to his own authorship. R. W Buss was commissioned to continue Seymour’s work, although his contribution was temporary, only contributing two illustrations for chapter three before he was replaced by Hablot K. Browne, who called himself Phiz, and who subsequently worked with Dickens on many of his books. That interim chapter 3, between Seymour’s death and Phiz beginning work (a chapter itself split into two sections in the original version), and Dickens’ comment in his preface that by the time of Seymour’s death “only twenty-four pages of this book were published, and when assuredly not forty eight were written”, suggests that it is not until chapter 4 that Dickens is writing again after the tragedy of Seymour’s death. And it’s an interesting opening to that chapter which touches upon the subject of authorship:

Many authors entertain, not only a foolish, but a really dishonest objection, to acknowledge the sources from whence they derive much valuable information. We have no such feeling. We are merely endeavouring to discharge in an upright manner, the responsible duties of our editorial functions; and whatever ambition me might have felt under other circumstances, to lay claim to the authorship of these adventures, a regard for truth forbids us to do more, than claim the merit of their judicious arrangement, and impartial narration.

The Pickwick Papers, Chapter 4, page 58

So, at this stage, Dickens still handily maintains the fiction of his original advertisement, that this is a ‘found’ account from Pickwick’s own papers. Nevertheless, perhaps having been freed from a commitment with Seymour – I can only speculate – but certainly understanding the original limitations of the work, as amusing as they may be, for a projected twenty instalment, Dickens began to grow his story into something somewhat more cohesive.

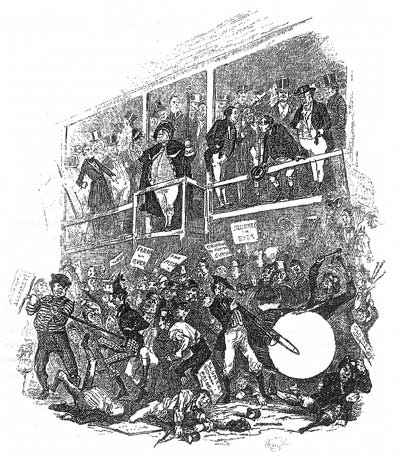

Dickens not only understood the limitations of the original concept of The Pickwick Papers; he also understood the literary antecedents upon which it rested. Dickens is clearly indebted to writers like Laurence Sterne and Henry Fielding for the satirical nature of the work, as well as Cervantes for providing the picaresque template which drives the narrative: Pickwick’s young side-kick, Sam Weller, is overtly associated with Sancho Panza, while Pickwick is Don Quixote, both travelling the countryside and falling into adventures. The story may have begun with the satirical nod at middle-aged sportsmen – the intention of Seymour’s original project – but Dickens is able to broaden his satire through his picaresque adventure. The ‘Nimrod Clubs’ that Dickens alludes to, also encompasses the gentleman’s clubs devoted to scientific advancement (as suggested by Pickwick’s reputation based on his study of Tittlebats, but also on his mistaken interpretation of an inscribed stone which the Pickwick club lauds him for, nevertheless) is one aspect of the satire. Yet, for a time, his satirical eye wanders, looking for a subject. The chapter about the Eatanswill local election is a great example of Dickens’ ability for social satire. The name, alone – Eatanswill – is enough to suggest Dickens’ feelings about politics. Added to that is the rival newspapers, the Eatanswill Gazette, supporting the Blue principles (whatever they are) and the Eatanswill Independent, supporting Buff Principals, which speaks to the generic colouring and pretence Dickens saw in any political posturing. There’s even a wonderful moment when Samuel Slumkey, the Blue candidate, goes all out to win votes by kissing babies. Some things never change!

There is also the matter of the various stories interpolated into the first half of the narrative. Of particular interest is the story of the ‘Goblin who stole a Sexton’, told to the party by Mr Wardle. The Sexton in question, Gabriel Grub, is a grouchy misanthrope who is pulled into the underworld while digging a grave on Christmas Eve by the Goblin. He is shown three visions: a scene showing the death of a child, another showing the death of the child’s parents, and a third showing a possible idyllic future. It is not a stretch to see that this is an early version of A Christmas Carol, and that that Dickens’ tendency to criticise the ill-treatment of the poor is already evident. Further to this theme, and of more consequence to The Pickwick Paper’s overall evolution, is the story told by an old man to Pickwick, of a young family caught in debt. The husband, sent to a debtor’s prison, dies, as does the young boy after him. The story is particularly poignant since Dickens’ own father spent three months in a debtors’ prison when he was a boy, and you can sense the pain of that in his description of the family’s pain, which can be read by clicking here.

As Dickens’ narrative progresses there is a sense that he is shifting focus more and more away from the sporting theme which was the project’s original focus, to themes more aligned with his own experience and concerns. His experiences as a child when his father was sent to prison, along with his background as a court reporter, become telling in the narrative, along with the misadventures of the Pickwickians, shifting from the masculine world of fighting, duelling, hunting and sport, to a more feminine world in which they are often truly out of their depth. Increasingly, the narrative focuses upon Sam’s interest in Mary, a house maid; in Tupman’s vain attempts to attract a woman; in Winkle’s troublesome pursuit of Arabella Allen, of her disapproving brother, Ben, and Winkle’s love rival, Bob Sawyer; or Snodgrass’ understated story romance of Emily Wardle. At times, The Pickwick Papers reads like an old Carry On movie, with wonderfully ridiculous set pieces in which Pickwick finds himself on the wrong side of decorum, despite his vain attempts to keep others in line. Of most interest is the story of Pickwick and Mrs Bardell, which eventually forms the backbone of the narrative. Dickens took inspiration for this part of the story from a real court case he had reported on, Norton v. Melbourne, in which the husband of Caroline Norton, sued the sitting Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, for adultery. Dickens doesn’t use details from the case. Rather, it is his experience as a court reporter that informs this aspect of the story. In it, Dickens ingeniously combines tragic and comic elements, as well as highlighting his contempt for the legal profession. Having thrown herself at Mr Pickwick and somehow interpreted his rebuffs as a promise to marry, Mrs Bardell sues Pickwick for breach of promise and wins, with the help of lawyers Dodson and Fogg. Pickwick, a man of principle, refuses to pay her her awarded damages, and instead chooses debtors’ prison. As much as Dickens has shown himself to be an adept comic writer, his portrayal of the misery of the prison system is realistic, already anticipated by the story told by the old man. And Pickwick’s experience serves to highlight another theme of the novel that widows are not to be trusted, as Sam Weller’s father, Tony, often states.

Despite this seeming slide towards the quotidian, Dickens understands that a basis of his fiction lies in exaggeration. His outrageously comical names, the farcical extremes to which he takes his narrative, anticipating much situational comedy, and the elevation of the quotidian to a heroic level, achieve this. Despite his being bald, corpulent and middle-aged, Pickwick is written as a valiant figure, praised beyond his desert by his author, which serves to make his shortcomings so much more humorous. In the same manner, the wicked Jingle is likeable and his manner of scatter-brained speech is endearing and picturesque. Sam’s loyalty, like his predecessor, Sancho, is sometimes inexplicable, but he is a worthy adversary for Pickwick’s enemies and gets things done. It is this elevation of the ordinary – of the mock-heroic pretensions of its protagonists – that I think underlies whatever else is happening at any time in the story. Dickens was clearly aware of this, and there are explicit allusions of the style, mastered before Dickens by writers like Fielding and Pope. Dickens alludes to this in his original advertisement for the project:

Seymour has devoted himself, heart and graver, to the task of illustrating the beauties of Pickwick. It was reserved to Gibbon to paint, in colours that will never fade, the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire – to Hume to chronicle the strife and turmoil of the two proud houses that divided England against herself – to Napier to pen, in burning words, the History of the War in the Peninsula — the deeds and actions of the gifted Pickwick yet remain for ‘Boz’ and Seymour to hand down to posterity.

It’s there in the early sections of the book which, Dickens’ early advertisement aside, signal the farcical nature of Dickens’ undertaking with mock-heroic tones. When Pickwick first meets Jingle and tells him that Snodgrass is a poet, Jingle claims also to write poetry:

‘Epic poem, — ten thousand lines — revolution of July — composed it on the spot — Mars by day, Apollo by night, — bang the field piece, twang the lyre.’

‘You were present at that glorious scene, Sir?’ Said Mr Snodgrass.

‘Present! Think I was; fired a musket, — fired with an idea, — rushed into wine shop — wrote it down — back again — whiz, bang — another idea — wine shop again — pen and ink — back again — cut and slash — noble time, Sir…’

The Pickwick Papers, Chapter 2, page 26

Putting aside the obvious anachronism – the July Revolution that deposed the Bourbon dynasty wasn’t to happen for another three years after 1827, the year this narrative is set – Jingle’s claim is both wonderfully ridiculous (that he wrote an epic poem while also fighting) and indicative of the exaggerated tone of the story. I think this is why the story is still somewhat cohesive, despite its strange beginnings. On the opening page we are told that Pickwick’s travels will result in “benefits which must inevitably result from carrying the speculations of that learned man into a wider field, from extending his travels, and consequently enlarging his sphere of observations; to the advancement of knowledge, and the diffusion of learning.” The fact that Pickwick’s perambulations never achieve such lauded results (apart from his erroneous interpretation of the “inscription of unquestionable antiquity” from which he derives even more undeserved commendation) is surely part of the point. Pickwick is at his best as a human being when events in the novel conspire to separate him from his pompous persona, and force him to make choices for the real betterment of others. That seems to be a fitting outcome for a character who was to launch Dickens’ career.

The Pickwick Papers is a great comic read. Dickens was a master at capturing the foibles of individuals and the ridiculous realities of life within deftly executed scenes. I think you need to approach this story on its own terms, one scene at a time, without fretting about a larger story arc to begin with. One – in fact several – arcs eventually emerge, along with likeable and grotesque characters, alike. I think the reason to read a book like this is because it is the sort of thing that is unlikely to be written now, and it’s a different kind of entertainment than we expect from modern writers. When you read The Pickwick Papers you get a sense of the debt other comic writers from England owe Dickens. His influence is evident in Pratchett’s Discworld Novels – Ankh-Morpork is nothing if not Dickensian – as well as the high farces of writers like Tom Sharpe and Wodehouse. Reading something like The Pickwick Papers is not only entertaining, but it gives a wider appreciation of those other works and helps set them within a cultural context.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!