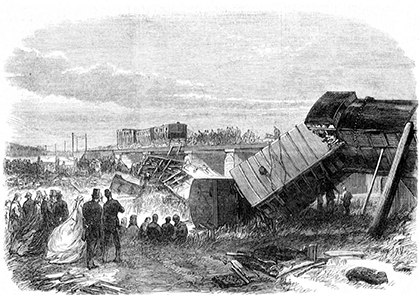

Charles Dickens was involved in a rail accident at Staplehurst on 9 June 1865. The train derailed while crossing a viaduct and ten people were killed and over forty injured. Dickens, while not physically injured, died five years later, to the very day. His son attributed his decline to the after-effects of the rail accident. Dickens recorded his experience of the accident and its effect on him in a letter to his close friend, Thomas Mitton. After the accident Dickens wrote the short story, The Signalman, and collaborated on a collection of short stories, Mugby Junction, which may have been inspired by another rail disaster, also. However, the accident at Staplehurst had no bearing on the writing of Dombey and Son, even though railways are important to the story. The book began its publication almost twenty years prior to the accident, serialised by Bradbury and Evans between October 1846 and April 1848 in twenty monthly instalments (the last two being a double publication). The book was published as a single volume in 1848.

When reading Dickens its always tempting to wonder how much of his own life informed his fiction. His childhood poverty is the subject of a lot of discussion relating to themes in his fiction: about the treatment of the poor, of children, of institutions and an economy that dehumanised them.

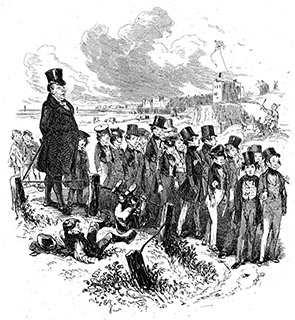

But in the case of Dombey and Son, specifically, it’s just as tantalising to wonder about contemporary issues, as well as how Dickens’s personal experiences while writing the novel may have shaped it. The growth of the railways is one aspect of this. During the 1840s a great deal of the London railway infrastructure was being built. Trains represented not only a new form of travel, but the continuing emergence of a new industrial society that was supplanting traditional social structures and attitudes to wealth and power. In chapter 6 of Dombey and Son Dickens’s narrator describes the destruction caused by the building of the railway lines. He describes it as an earthquake that has:

. . . rent the whole neighbourhood to its centre. Traces of its course were visible on every side. Houses were knocked down; streets broken through and stopped; deep pits and trenches dug in the ground; enormous heaps of earth and clay thrown up; buildings that were undermined and shaking, propped by great beams of wood.

The modern world is ripping through and supplanting the old. For many in Dickens’s contemporary audience this sense of destruction must have been palpable. The new world and old were shunted against each other, where,

There were frowzy fields, and cowhouses, and dunghills, and dustheaps, and ditches, and gardens, and summer-houses, and carpet-beating grounds, at the very door of the Railway . . . Nothing was the better for it, or thought of being so. If the miserable waste ground lying near it could have laughed, it would have laughed to scorn, like many of the miserable neighbours.

That’s a contemporary issue. There is also the tantalising detail of how Dickens began writing the novel. In his preface to the 1858 Cheap Edition, Dickens states, “I began this book by the lake of Geneva, and went on with it for some months in France.” Given this, it’s hard not to speculate about the locations Dickens chose for the climactic scenes of the story. James Carker hides out in the town of Dijon in France, almost halfway between Geneva and Paris, where Dickens spent a great deal of time. He first flees northward towards Paris and then back into England on his epic journey, ending up at a small town on a railway junction, possibly Paddock Wood in Kent, where a branch line was opened in 1844.

However, for a book of almost a thousand pages, railways, specifically, in fact, have very little space devoted to them. Mr Toodle, whose wife Polly is employed by Dombey as his son’s wet nurse, is an engine driver, and Toodle feels positive about the railway since it employs him. It is not surprising that the nickname of Toodle’s oldest son, Rob, is merely a contraction of ‘boiler’ (Biler). And it’s hard not to wonder at Dickens’s naming of Mr Toots, a former school friend of young Paul Dombey who becomes a part of the family’s life. Although Toots has nothing to do with railways. He’s a simple but obliging fellow, and somewhat charming in his good nature.

But the issue of what the railways represent about 19th century society and its attitudes: those values of progress, industrialisation, and the transformation of trade and wealth, with the attendant shift towards mercantile influence in a society predicated on traditional class structures. Mr Dombey is wealthy but he is not a gentleman. He is a part of that newer breed of men who possess mercantile wealth and wish to make their own mark in the world. Dombey has status, wealth and power, with all the trappings that signify this. What he has been lacking, however, is a son to fill an absence in the firm’s traditional title, Dombey and Son. A son will confer a sense of continuity and legacy. So when Paul Dombey is born in the first chapter, his birth is reason for some joy, except that it marred by the death of his mother, Fanny.

Fanny’s death is the catalyst for much of the rest of the story. Dombey hires Polly Toodle as Paul’s wet nurse. The stringent conditions of her employment imposed by Dombey – his insistence there be no emotional connection between his son and Polly, and his insistence on calling Polly ‘Mrs Richards’, thereby denying her an identity in the household – speaks to Dombey’s character: Dombey is proud, determined and emotionally distant. His personal qualities represent a class of men: impersonal and demanding. He is not so much upset at the death of his wife, as the potential danger the death poses to his newborn son: “That the life and progress on which he built such hopes, should be endangered in the outset by so mean a want; that Dombey and Son should be tottering for a nurse, was a sore humiliation.” Women, it seems, are the mechanism by which the domestic machinery of life operate, through which a business dynasty may be founded, and as such have little emotional weight in the life of a man like Dombey. Women merely supply the needs of the masculine world of economy and trade. Susan Nipper, Florence’s young maid, tells Polly, “girls are thrown away in this household”. And it is Polly who gives comfort to Florence after the death of her mother, telling her, “she went to GOD!” For his part, Dombey finds it difficult to connect with his daughter. His memory of his dying wife – his sense that he stood apart from her death and merely observed his daughter’s comforting of her mother – speaks to a degree of emotional detachment that threatens to metastasise into estrangement from Florence; even a feeling that, “he might come to hate her.” Later Dombey will be embittered by his son’s death and his daughter’s survival; that she has won his son’s affections and his new wife’s heart while she remains aloof from him: “. . . he had often glanced uneasily in her motherless infancy, with a kind of dread, lest he might come to hate her, and of whom his foreboding was fulfilled, for he DID hate her in his heart.” When Dombey first speaks directly to Florence in the novel, he asks, “Do you know who I am?”

Given the importance of trade to Dombey and his desire to create a family name that will survive him, the title of this novel is worth considering for a moment. It is something of a misnomer. The full title (Dealings with the Firm of Dombey and Son, Wholsesale, Retail and for Exploration) suggests a story concerned with Dombey’s masculine world of trade and deal making. Young Paul, we might expect, will grow to assume the place of his father in the business: that he will be the hero of this story, perhaps humanising his father while at the same time helping to consolidate the place of their business in the world. But this is not Dickens’s story at all. By chapter 16 young Paul has died. Dombey and Son is not a triumphal tale; rather, it is a story of grief, conflict and dysfunction which more broadly reflects the opposing tenants of this masculine world and an emergent female identity, if I may somewhat simplify a complex and sprawling narrative.

It’s worth noting here that in his later career Dickens often did public readings from his novels, lasting up to an hour and a half. He even had a small table designed for the stage as a prop for his readings. In the case of Dombey and Son, Dickens extracted the story of Paul Dombey from the novel, distilling it into the key events of Paul’s life – his birth, his youth, his time as a student in Doctor Blimber’s school, and his demise and death – to create The Story of Little Dombey. You can watch a video about Dickens’s prompt book of The Story of Little Dombey that he used on stage, as well as download the complete story (which can be read within an hour), by clicking here. Dickens was an amateur actor and while reading the story he would affect the voices of his characters, dramatizing scenes which he knew mostly by heart. He would even cry on stage for his audience at the death of Little Dombey. Readings of The Story of Little Dombey became a favourite for Victorian audiences. Extracted from the larger story in this way, The Story of Little Dombey recalls to mind the story of Little Nell in The Old Curiosity shop, or Smike from Nicholas Nickleby: young people who die in angelic innocence. The Story of Little Dombey, as well as its source material, is full of the imagery of rivers and waves (the whole novel is full of nautical imagery and rivers and waves are associated with death: the chapter in which Mrs Skewton dies is called ‘New Voices on the Waves’). Young Paul has a vision that he is being carried out to sea with a distant shore approaching and someone – his mother? – awaiting on a farther bank. It’s the kind of sentimentality that made The Old Curiosity Shop so popular with Victorian audiences, but which often jars with modern sensibilities. Instead of becoming the next instrument of trade and industry, Paul is appropriated into a new role by the narrative, as an “old-fashioned” boy. The term is applied to him repeatedly as it becomes clear that he will not survive:

The golden ripple on the wall came back again, and nothing else stirred in the room. The old, old, fashion! The fashion that came in with our first garments, and will last unchanged until our race has run its course, and the wide firmament is rolled up like a scroll.

The ‘old-fashion’ describes that state of the soul in unison with God, unsullied by the baser concerns of the world; imbued, instead, with Christian spirituality.

It’s interesting what Dickens has done here. The title of the novel sets up expectations which Dickens has no intentions of meeting. Its hero, if we wish to call Dombey senior that, is unsympathetic and cold. We only understand that he is a hero because we see that he is on a journey. But that journey is long and his awakening is late. Yet we know he is not the villain because Dickens provides us with a deliciously awful villain in the person of Mr Carker, Dombey’s own manager at Dombey and Son (the closest comparison is possibly Ralph Nickleby, from the first of Dickens’s social novels with a more sophisticated villain), and his all-too-white, all-too-perfect teeth, which take on a threatening aspect of their own. Our best other choice if we need a hero, Walter Gay, has been sent off to Barbados and has presumably died in a disaster at sea. The novel is sombre. The life of Dombey and his daughter is fraught with emotional withholding, grief and despair. Dombey’s world resides in his business, and his personal life is stymied by the masculine tenets upon which his business world has previously flourished. Dombey represents the worst of masculine values unmitigated by love or family. His redemptive path is towards an understanding that only his daughter can provide.

So, the novel establishes several dichotomies of value and character. Against the rush of progress and business lies the old-fashioned virtues of God and home. Against the cold, proud intransigence of Dombey’s masculine demand for obedience lies the restorative potential of feminine love.

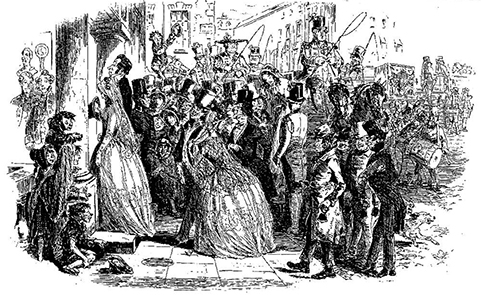

This is not to say that all women in Dombey and Son are exemplars of nurturance and domesticity. Mrs Pipchin who runs a boarding house at Brighton where Paul is sent to recuperate is cold and unlikable. She wears mourning clothes some 40 years after her husband’s death and is described in the text as an “ogress and child-queller”. Mrs MacStinger, landlady to Captain Cuttle, a friend to Walter’s uncle Sol, is a shrewish woman determined to control all aspects of the Captain’s life. And Mrs Skewton, mother of Edith Granger, whom Dombey will marry, is a scheming woman who places ambition above maternal affection. “What childhood did you ever leave to me?” Edith asks of her mother, “I was a woman – artful, designing, mercenary, laying snares for men – before I knew myself, or you, or even understood the base and wretched aim of every new display I learnt.”

“. . . not an orphan in the wide world can be so deserted as the child who is an outcast from a living parent's love.”

Dombey and Son, Chapter XXIV, page 381

Even Edith, who becomes Florence’s step-mother – and who shows a great deal of love and understanding to Florence – presents as cold, controlled and proud. Edith’s character is another point at which we may wonder about the zeitgeist as Dicken’s was writing this novel. One is tempted to call Edith a proto-feminist, but reading her now, she feels entirely modern. Edith rails against her situation as a woman and her mother’s machinations. Her mother has raised her with all the ‘accomplishments’ of a young lady, that she might be more marketable for marriage. It’s a word that reminds us of Austen’s women almost forty years before, and young Mary Bennett, who imposes those ‘accomplishments’ on all unfortunate enough to be within her orbit, without her seeming to understand their purpose. For her part, Edith understands that her accomplishments and beauty make her little more than chattel, a point of view she frequently articulates:

He [Dombey] has considered his bargain; he has shown it to his friend; he is even rather proud of it; he thinks that it will suit him, and may be had sufficiently cheap; and he will buy tomorrow.

That Edith despises her position is evident. And her refusal to bend and her pride in her independence puts her on a level equal to Dombey, for she is just as intransigent as he. Of Dombey we are told, “His pride was set upon maintaining his magnificent supremacy, and forcing recognition of it from [Edith]”, and that, “He had resolved to conquer her”. Edith, on the other hand, has already spent what capital a woman has in a first marriage – both her first husband and son have died – and while she remains beautiful, “she seemed with her own pride to defy her very self.” Edith refuses to use the wiles her mother taught her, to lure Dombey to her, and his acceptance of her despite this cold display undermines his power over her:

‘Did I ever tempt you to seek my hand? Did I ever use any art to win you? Was I ever more conciliating to you when you pursued me, than I have been since our marriage? Was I ever other to you, than I am?’

Dombey may insist, “I will have submission”, but his ultimatums are met with Edith’s equally strong determination, “I will do nothing that you ask.”

Dombey’s campaign to receive traditional female subservience from Edith, and her refusal to acquiesce, not only to Dombey but to the very tenets of the institution of marriage that socially moulds women, makes her feel vibrant and modern to us. In her clash with Dombey we see the most explicit representation of the tensions within the novel. These may not strictly be dichotomous, since Edith’s stand is against the traditions of Christian patriarchy, too, but she more explicitly stands in opposition to the tenets of the emerging power of capital to shape the world to its own whims.

“I will hold no place in your house to-morrow, or on any recurrence of to-morrow. I will be exhibited to no one, as the refractory slave you purchased, such a time. If I kept my marriage-day, I would keep it as a day of shame. Self-respect! appearances before the world! what are these to me? You have done all you can to make them nothing to me, and they

are nothing.”

Dombey and Son, Chapter XLVII, page 712

That we understand this more completely, we can turn to the minor character, ‘Good’ Mrs Brown and her daughter, Alice. When Harriet Carker, sister to our villain, James Carker, chances upon Mrs Brown and her daughter on the road at night, she gives them alms. When it becomes apparent that Harriet is related to Carker, the two women, poor but proud, walk to Harriet’s house to return the money. Carker, whom we might read as Dombey’s more evil and less redeemable self, has taken sexual advantage of Alice. Like Edith, Alice refuses to be bought by wealth: to trade herself as chattel for security or acceptance. Dickens establishes the theme across a social spectrum rather than making it specific to Edith.

For Dombey, redemption lies not in wealth or success. Dombey’s road to redemption lies through his daughter, not through business acumen. When his son Paul dies, Mrs Tox, a friend to Dombey’s sister, remarks “To think . . . that Dombey and Son should be a daughter after all!” This would seem to be the simple solution, that Dombey and Son should resolve itself with an approximation to a kind of modern feminist credo, ‘Girls can do anything’, and as modern readers, we may take interest in this emergent feminist discourse and be satisfied. And I think Dickens is interested in this aspect of his story and is aware of this kind of thinking, too. After all, Mr Toots alludes to “the Rights of Women” which will be attended to through the powerful intellect of his own new bride. Here we have reference to Mary Wollstonecraft’s seminal feminist work, signalling that Dickens is thinking seriously about not only the changing economic but also changing social structures of society.

Yet we should also understand that Dickens is still of his time. Jack Bunsby is comically forced into marriage by Mrs MacStinger, and Captain Cuttle fears he may be the next to be caught if Mrs Bokum has her way. The predatory female is a stock character we can trace back as early as The Pickwick Papers, wherein the unscrupulous Mrs Bardell tries to sue Pickwick into marrying her.

So, Dombey and Son still has flashes of Dickens’s humour, even if this is a more sombre and serious novel. But on the whole, Dombey and Son tells a moral story about the emerging modern world of the 19th century, and it dramatizes the tenets of feminism in a way that are still relatable. Up to this point in Dickens’s career, Dombey and Son feels like the most accomplished of his novels. While Dickens would continue to publish his novels in serial form until his death, the influence of that publishing regimen is not as evident in this story as in his previous books. It is obvious that Dickens has planned his narrative carefully and he has abandoned the picaresque tradition evident in previous books. If I had to draw a line somewhere in Dickens’s career to say that this was the point where Dickens really began to understand and execute his craft more maturely, I would pick Dombey and Son to mark that moment.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!