The Old Curiosity Shop was Dickens’s fourth novel. Like Oliver Twist, key aspects of the plot are so well known that I will assume they are at least familiar to readers, and I will discuss them in this review. So, now is the time to stop reading if you are not familiar with the book but are interested in reading it without major spoilers.

The Old Curiosity Shop is a curious novel in itself. Unlike modern novels, which are usually published complete, The Old Curiosity Shop was published as a periodical like other Dickens novels. But there was a difference. The novel emerged as a kind of experiment. Dickens had started his own periodical, Master Humphrey's Clock, which was intended to be published weekly. Dickens’s previous novels had been published in monthly instalments. But Dickens’s idea was that his new magazine would incorporate contributions from other writers, as well as himself, and would employ several illustrators to cope with the demands of a weekly periodical. As a result, The Old Curiosity Shop has two major illustrators, George Cattermole and Hablot K. Browne (known as ‘Phiz’, his key illustrator since The Pickwick Papers), as well as two drawings from two other illustrators, Samuel Williams and Daniel Maclise. And instead of subjecting himself to the pressure of producing 32 pages a month, as he had done in the past, Dickens intended that his contributions to Master Humprhrey's Clock could be more sporadic. Unfortunately, as a publication trading on Dickens’s fame, it did not do as well as hoped when this became apparent to the public, so when the story of little Nell became immensely popular – he only intended to produce chapters for it at irregular intervals – he was again forced into the position of producing regular copy. Except now, Dickens had to deliver copy weekly, not monthly. But it worked. Master Humphrey's Clock sold well, as high as a hundred thousand copies a week.

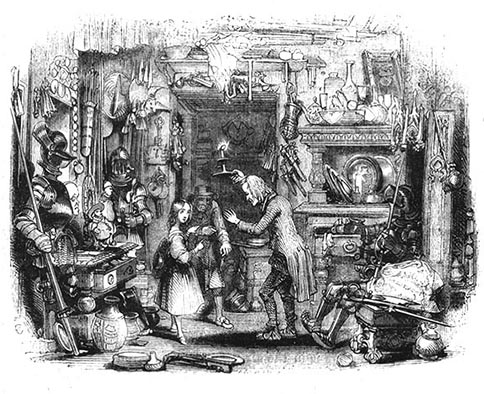

It is this strange genesis which results in one of the peculiarities of the novel: it begins as a first-person narrative, which may have been jarring for readers of Dickens’s contemporary audience. As a satirical writer with an interest in serious social issues of his time, Dickens’s usual third-person narrative is a more flexible tool to broadly paint the world of his characters and provide the narrative distance needed for his comedy, notwithstanding two of his most famous novels, David Copperfield and Great Expectations, both written in first person. But these were yet to come. The conceit of Master Humphrey's Clock, that the tales appearing in it are taken from manuscripts stored in the clock by Mr Humphries’s fireplace and are randomly selected by him for his readers, shapes the opening chapters of the novel. Mr Humphries is supposed to be the first-person narrator of The Old Curiosity Shop, although he is never named in the novel as it now appears. His role is to introduce us to Nell and her grandfather. On one of his late-night walks through London he bumps into Nell, who has become lost in the dark, and he helps direct her back home. We have a sense that all is not well in Nell’s home life. She lodges with her grandfather in an old shop of curiosities. The atmosphere of the place is morose and barren, certainly not a good environment for a young girl. Our narrator is further concerned by Nell’s grandfather leaving her at home at that late hour in his care, a stranger. It is through our narrator that Dickens imparts key aspects of Nell’s character and the story. “So very young, so spiritual, so slight and fairy-like a creature passing the long dull nights in such an uncongenial place…” he observes, telling us all the most essential aspects of Nell’s character in a single sentence. In a further comment, almost metatextual, he states “she seemed to exist in a kind of allegory.”

The fact that Dickens dismisses his narrator from the narrative by the end of the third chapter suggests the difficulties inherent in producing fiction on the fly. The narrator had suited Dickens’s initial intentions for Master Humphrey's Clock, but Nell’s character and the mystery of her grandfather were the obvious focus of the story and a first person narrator had little to do but observe, and possibly complicate things with questions about his own involvement, not to mention the more limited perspective of the first person narrator. So, Dickens unceremoniously retires his narrator – “And now that I have carried this history so far in my own character and introduced these personages to the reader, I shall for the convenience of the narrative detach myself from its further course…” It’s clumsy, but to have continued would have made the narrative increasingly clumsier.

The Old Curiosity Shop has similarities in plot to Dickens’s previous novels, and further develops some of their themes. Nell, like Oliver and Smike (from Nicholas Nickleby) before her, is an orphan. And like them, she flees from a threatening situation and is pursued by a villain. Oliver was pursued by Bill Sikes and Fagin. Smike was pursued by Wackford Squeers and Ralph Nickleby. Nell is sought by Dickens’s grotesque Daniel Quilp, a misshapen dwarf, evidently characterised to exploit Victorian prejudices, and as well by the single gentleman (unnamed) for more benevolent purposes. Like Dickens’s previous villains, Ralph Nickleby and Bill Sikes (as well as Fagin, whose fate is far happier in Carol Reed’s 1968 film adaptation of the musical than in Dickens’s novel), Quilp also comes to a nasty end, suggesting a rebalancing of life’s moral ledger. Dickens’s villains die violently, with no chance of reflection or redemption, while the death of characters who have suffered at their hands, is akin to a peaceful slumber, preceded by a long acceptance and an assured path to heaven. Nell’s death is often criticised as overly sentimental. Oscar Wilde famously said “one must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without dissolving into tears . . . of laughter”. But her death was highly moving for Dickens’s Victorian audience, and merely extended the sentimental, even hagiographic treatment, of earlier characters. The dreaded anticipation of her death was palpable for Dickens’s audience. The story of crowds gathering at the harbour in New York, calling for news of the next instalment of the story, asking those aboard whether Nell was dead, is testament to the power of Dickens’s appeal in 1841. Dickens, himself, was said to have broken into tears at having killed her, although it seems apparent that Nell’s death was inextricably linked to the death of his sister-in-law, Mary Hogarth, in 1837; a death which likely found its fullest expression in this third book featuring orphan children.

The Old Curiosity Shop is not a sentimental break from the social realism of Dickens’s previous two novels, but a fuller realisation of sentimental elements already introduced in those fictions. While Nicholas Nickleby and Oliver Twist represented a harsh reality for the poor of Dickens’s time, they also seek to tug at the heartstrings of Dickens’s readers. Similarly, The Old Curiosity Shop is a peculiar blend of social realism and religious allegory. While Oliver was to enjoy a happy, fairy tale conclusion, Dick, another workhouse boy from the same novel, long anticipates his own death and contemplates heaven: “I know the doctor must be right, Oliver; because I dream so much of heaven, and angels, and kind faces that I never see when I’m awake.” Smike also anticipates his own death, which is tinged with religious sentimentality. Smike cannot bear to say goodbye to Kate, whom he secretly loves, fearing it will be forever. When Nicholas assures him he will meet Kate again, Smike replies, “In heaven – I humbly pray to God – in heaven.” And his death scene offers a vision of that heaven. We are told that:

He fell into a slight slumber, and waking, smiled as before; then spoke of beauteous gardens, which he said stretched out before him, and were filled with figures of men, women, and many children, all with light upon their faces; then whispered that it was Eden – and so died.

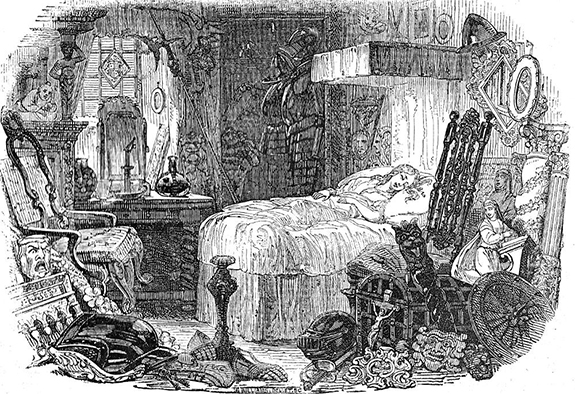

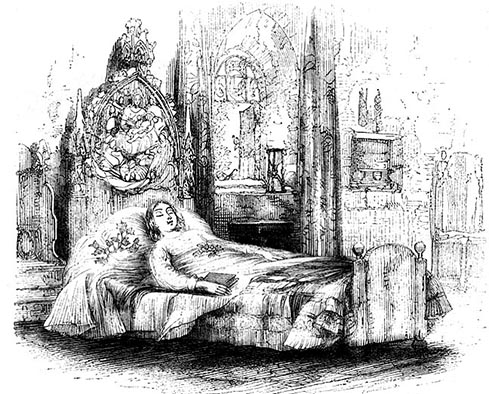

Nell, on the other hand, dies off stage. The pathos of her death seems to lie, first, in our having missed it; having travelled in the coach with the single gentleman, Mr Garland and Nell’s childhood friend, Kit, their primary fear being they might miss her if she once again moves away and leaves no knowledge of where she has gone, we instead find that she has died.

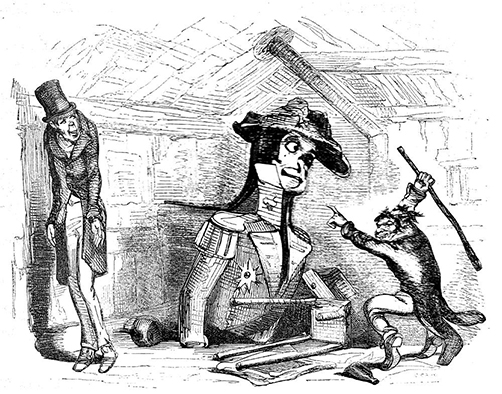

So, Nell’s death, while too sentimental for some modern readers, is nevertheless in keeping with the death of characters in Dickens’s previous two novels. While there are many internal clues that Nell’s fate will be death – she is described as angelic, is constantly referred to as a child but never a woman, she identifies with other dead children, hangs around grave yards and has a lingering illness that progresses throughout the story – the trajectory of Dickens’s writing career should also have been something of a hint to his contemporary audience. In Oliver Twist, Oliver’s angelic innocence mirrored in Dick: like a pure part of Oliver, his death is cathartic, releasing us from our fears for Oliver, and thereby licencing Oliver’s miraculous ending. In Nicholas Nickleby, Smike appears as a more innocent and simple counterpart of Nicholas, himself, again allowing Dickens to separate the worldly and spiritual in his characters. But Nell embodies both aspects of these characters. She lives in poverty but her concern in fleeing London is for her grandfather: his failing state of mind, his penury and spiritual health. They flee to the countryside when it becomes clear that Daniel Quilp, who is owed a substantial amount of money by Nell’s grandfather on account of his gambling – her grandfather has foolishly attempted to win money to leave an inheritance for Nell – will take their house and shop. Travelling from place to place, they fall in with various people: Mrs Jarley owner of Mrs Jarley’s waxworks, with Jerry and his dancing dogs, and even the purveyor of a Punch and Judy Show, Mr Harris. To a degree, Nell’s adventure into the wider world is similar to Nicholas Nickleby’s who finds himself employed as writer and actor in a theatre. Similarly, Nell’s beauty and innocence is exploited by Mrs Jarley to draw crowds to her waxworks.

The novel has a picaresque element with this wandering around the countryside, although the effect is less Fielding or Smollett, and more Bunyan, for Nell’s journey is spiritual. In an industrial town, Nell and her grandfather are exposed to the harsh realities of industrialisation, where “the water had become thicker and dirtier” and “tall chimneys vomit[ed] forth a black vapour, which hung in a dense ill-favoured cloud above the housetops and filled the air with gloom…” The people of the town are either prosperous or poor: “some wore the cunning look of bargaining and plotting, some were anxious and eager, some slow and dull: in some countenances were written gain; in others loss.” This is the social realism that Dickens is known for. In the industrial town people’s lives are miserable and their spirits cheapened. Yet, at the same time, Dickens is also writing an allegory. Nell’s journey through the countryside echoes that of Christian’s journey in The Pilgrim’s Progress, with several references to that work. It is interesting that Dickens, known for his sometimes bizarre character names, chooses to leave several characters unnamed in the novel, or mostly referred to their social positions, like characters in an allegory: the small servant; the single gentleman; the schoolmaster (otherwise Mr Marton); and the furnace man. Facing the prospect of sleeping on the streets of the industrial town, Nell and her grandfather are offered a warm place to sleep by the furnace man. So, they rest that night in the warmth of a fiery hell that is never extinguished. This contrasts to the pastoral scenes in which Nell and her grandfather escape into pre-industrial England, representing a kind of prelapsarian wholesomeness:

‘…Oh! If we live to reach the country once again, if we get clear of these dreadful places though it is only to lie down and die, with what a grateful heart I shall thank God for so much mercy’

With thoughts like this, and with some vague design of travelling to a great distance among streams and mountains, where only very poor and simple people lived, and where they might maintain themselves by very humble helping work in farm, free from such terrors as that from which they fled…

Nell’s suffering, like the countryside of England, is transcendent. As Nell further succumbs to her illness, the sense of her moral purity is heightened:

With failing strength and heightened resolution, there had sprung up a purified and altered mind; there had grown in her bosom blessed thoughts and hopes, which are the portion of the few but weak and drooping.

Nell also unconsciously associates herself with the death of the little scholar, the best student of the country schoolmaster:

Again too, dreams of the little scholar; of the roof opening, and a column of bright faces, rising far away into the sky, as she had seen in some old scriptural picture once, and looking down on her, asleep. It was a sweet and happy dream. The quiet spot, outside, seemed to remain the same, save that there was music in the air, and a sound of angels’ wings.

The “column of bright faces” recalls the “light upon their faces” witnessed by Smike before his Edenic rapture. Dickens’s portrayal of Nell accords with Christian hagiographic traditions: that martyrdom and suffering have associations with purity and spirituality; that the physical body must be eschewed for that of the soul and a oneness with God. It would seem appropriate, then, and a logical extension of the visions of heaven and angels throughout the novel, that George Cattermole’s final illustration for the book should be of Nell ascending to heaven in the arms of angels.

But the problem the novel faces – and I think this is the same of Richardson’s Pamela, a novel I think Fielding justifiably lampooned – is that Nell’s goodness has little dramatic potential, except to inspire pathos. Perfection such as Nell’s need not change, and so true narrative interest lies outside the scope of her character. What we expect of Nell – and what we get – is goodness moving towards perfection. Beyond that, Nell never really develops as a character. Her grandfather is more interesting to us as a flawed human being. His addiction to gambling, which he tries to justify as a means to serve Nell’s future interests, culminates in a gripping scene in which he steals the only money they have from her. But there are real villains in the story too, and they tend to offer its most entertaining aspects. Sampson Brass and his sister, Sally, make excellent henchmen for the notorious Quilp. As lawyers (Sally, as a woman cannot officially be a lawyer, but she knows as much, if not more, than her brother) they find themselves embroiled in the machinations of Quilp, in his desire to do harm, even if somewhat pointlessly. Their framing of Kit, Nell’s childhood friend, for the theft of £5, recalls Mr Pickwick’s incarceration for the false accusation brought against him by Mrs Bardell. But it is Quilp who truly represents the moral polar opposite of Nell. He is a depraved man whose lubricious remarks about Nell, if nothing else, should alert us to his character: “She’s so … so small, so compact, so beautifully modelled, so fair, with such blue veins and such transparent skin, and such little feet…” he tells Nell’s grandfather. His emphasis on Nell’s size seems creepier when we remember his own stature as a dwarf: the implicit suggestion that Nell, a girl not yet fourteen, might be right for him; “Such a fresh, blooming, modest little bud … such a chubby, rosy, cosy, little Nell!” There is also a wonderful scene in which Quilp makes his tired wife stay up all night with him, forcing her to light each cigar, one after another, until the morning; or the scene in which he returns home to take delight in shattering her hopeful emotions, when she has come to believe he has drowned. But Quilp’s evil extends far beyond that, and those are details best left to a first reading.

Yet there are also characters on the side of good who are capable of piquing our interest. Dick Swiveller, like Sam Weller from The Pickwick Papers before him, is a down-to-earth fellow and we tend to like him. Initially intended to be the dupe of a plot between Quilp and Nell’s older brother, Fred, Dick changes throughout the course of the novel. Part of this may be attributable to the serialising of the story, which meant Dickens sometimes changed his intentions as he wrote. But Dick’s relationship with the unnamed small servant whom he call the ‘Marchioness’, is warm, funny and a good foil for the darker elements of the plot. And Kit’s unintended ensnarement in Quilp’s plans provides a surrogate for Nell who is absent. But he exists convincingly as a character in his own right, as well. His concern for his family or the pride he takes in being able to control Mr Garland’s pony, Whisker, when no one else can, makes him likeable. Mr Garland, however, is of that uncomplicatedly good ilk, much like Mr Brownlow in Oliver Twist.

Nevertheless, I think there are elements of the Nell story that may still appeal to modern readers unwilling to accept her otherwise unmitigated goodness and the pathos she is meant to inspire in her reader. The premise of Nell’s story is that the world, to a degree, is corrupt, and that true perfection cannot easily exist in such a world. This represents a separation between the concept of self and the physical body, since this essential self must separate from its physical container in order to achieve its final form. There are scenes, however, in which I think Dickens brings a reader closer to a modern conception of death and self. When Nell finally settles in a small village where she is given a paying position in the church, she meets the sexton who is digging a hole for a woman whom he believes to have been younger than himself: sixty-four years old, he guesses. But as he discusses the matter with his companion, David, they decide that she must have been older – certainly older than them – so they suppose she must have been eighty-nine, then unsatisfied with that, as old as a hundred. Nell, who considers the sexton old, wonders why he will want a new shovel next year. The sexton, on the other hand, can only convince himself he has many more years left of life by extending the age of the dead woman well beyond his own. His self-deception is very human and relatable. Later, the sexton takes Nell to an old well inside the church, which was once a monastery. The well is little more than a hole in the floor with a windlass and bucket. Like a life running out, the old well has dried over time, but its dark nothingness remains to be looked into, “like a grave itself”, the old sexton tells Nell. There is an existential horror of contemplating a darkness like this; a place that might swallow you up with one false step.

Overall, The Old Curiosity Shop is an uneven read for modern audiences, particularly those of a secular mind. But that is not to say that the book is such a stark departure from what Dickens had already written. There is something of Nell in Oliver, for instance. Oliver is pure and uncomplicated, but Dickens was following a different playbook when he wrote Oliver Twist. Oliver represents the miraculous fairy tale that Dickens anticipates when he writes about chimney sweeps who come from noble families in Sketches by Boz, and will one day be restored. Nell, on the other hand, is the product of a Christian tradition. Like Bunyan’s Christian, she is on an allegorical journey. Like the martyrs of the church and its saints, her concerns are increasingly removed from the physical privations that beset her and her grandfather. Modern readers may scoff at Nell’s death, but journeys of redemption and enlightenment still appeal to the modern mind. The musical Les Miserables, for instance, is nothing if not a religious journey of redemption. While Nell’s death may or may not strike the same chord it did for Dickens’s audience, alongside that are elements that are still loved by modern readers: Dickens’s wit, his representation of Victorian England, his villains, and a good dose of social justice.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!