By the time Dickens’s earliest work was printed as a single volume in 1839, Sketches by Boz had already enjoyed several publications in various forms. The book is not a single story. Rather, it is a collection of scenes from London life, descriptions of character types and anecdotes about London lives, as well as a series of short stories that form almost half the volume. It represents the beginning of Dickens’s writing career, compiled from works published in newspapers and periodicals. It’s a good place to start reading Dickens if you’re interested, for instance, in tracing his development as a writer. The Sketches were originally published anonymously. In fact, Dickens wasn’t even paid for his earliest work and his name wasn’t associated with the Sketches until he gained notoriety from The Pickwick Papers . The name ‘Boz’ derived from a nickname for a brother. As I read the Sketches I sometimes sensed that this anonymity was an advantage to Dickens. It allowed him to attain a level of credibility in his early writing that would have been difficult to achieve for a young man. He was only 21 when he published his first story, and by the age of 24 he had written most of the pieces for this volume. It is not surprising, then, that he sometimes assumes a much older persona: “In our earlier days,” he writes as he introduces his subject in ‘Greenwich Fair’, and he later states, “We have grown older since then, and quiet, and steady.” It’s a conceit subtly introduced into ‘The Last Cab-driver, and the First Omnibus Cad’, with its sense of nostalgia and loss, and its implicit experience of London from the perspective of an older man: “there is one who made an impression on our mind which can never be effaced”; “The last time we saw our friend”; “the appearance of the first omnibus”; “the class of men to which they belonged are fast disappearing.” Dickens is not just writing about London: he is establishing a persona – Boz – who is not a twenty-something newcomer, but an older, more mature man; a purveyor of opinions; a man wise and experienced enough to rail against politicians and expose human foibles.

Publication of Dickens’s first book didn’t happen as aspiring young writers might now expect. He wrote for magazines and newspapers that were hungry for copy. As a result, his pieces were published singly, to begin with. The Sketches, themselves, as they eventually came to be arranged, suggest, somewhat misleadingly, a progression, divided as they are into four sections that begin with mostly descriptive works, which evolve into more fictive works, and later, short stories. The first section, Seven Sketches from Our Parish describes London life in the 1830s, beginning with functionaries like the beadle and clergyman. Even here, though, Dickens draws from life, with some of his types actually based upon real people from his local parish. This is the unifying theme of the first section of the book: the parish and its people. As twenty-first century readers, we glimpse a world that often seems quaint, mannered and stylised, but through Dickens’s pen, is painted as realistically as our own, both in its absurdity and pretence, in its drama and tragedy.

The second section, entitled Scenes, focuses on various places and institutions in London. Beginning with scenes of London in the morning and London at night, Dickens moves on to discuss subjects as varied as the London courts, Hackney Coaches, a local circus, private theatres, London gardens, gin shops and charity dinners.

The third section of the book, entitled Characters, demonstrates a broader fictionalising of Dickens’s observations and his ability to satirise his subjects. There is the lamentable John Dounce, who throws away his freedom by marrying his cook after long years of bachelorhood. In the hilarious ‘Making a Night of It’, Dickens describes what is ostensibly a 1830s pub crawl that ends in drunkenness and debauchery. And there are more serious pieces, too, like Dickens’s critique of poor manners and aggression in ‘The Parlour Orator’, or the tragic ‘The Hospital Patient’, dealing with the issue of domestic violence, which seems just as relevant now as it must have been for Dickens’s audience.

Finally, the fourth section, entitled Tales, suggests Dickens’s progress towards his career as a writer of fiction. However, as much as we might wish to see the order of the Sketches as a record of Dickens’s development as a writer, the original order for publication of these disparate works was entirely different to their final arrangement as Sketches by Boz. Some of the stories in this later section were actually published quite early. For instance, Dickens’s first ever published work was in December 1833. It was ‘A Dinner at Poplar Walk’, which was renamed ‘Mr Minns and His Cousin’ when it was included in this section of the Sketches, as they finally came to be arranged. Nevertheless, it is in this section that we experience Dickens as we are most familiar: as a great fictional writer, capturing the absurdities and tragedies of life, and telling entertaining stories about Londoners.

There is a broad overview of the entire Sketches after this review. It gives a sense of the subject of each piece, but usually leaves out enough detail for the reader to make their own discoveries. Nevertheless, if you’re genuinely interested in reading Sketches by Boz, you may wish to avoid the overview and use it as an easy reference after you have finished reading.

So, what became known as Sketches by Boz began as individual publications, starting with ‘A Dinner at Poplar Walk’ in 1833. Eventually, they were compiled into two volumes in 1836 under the current title. It wasn’t until 1839 that the Sketches were published as a single volume, arranged as they now are for the first time. But before that, between 1836 and 1839, the Sketches were republished in monthly parts to cash in on the popularity of Dickens’s first novel, The Pickwick Papers, itself being published concurrently in monthly parts. Dickens would revise the Sketches for later editions, making small edits, mostly to avoid the potential for offence, for instance, against religious sensibilities. In his preface to the 1850 edition, he described the work as his “first attempts at authorship” which he described as “crude and ill-considered, and bearing obvious marks of haste and inexperience”. It is certainly true that the Sketches aren’t as well developed as most of his work, but the talent is obvious in the writing and Dickens adopts his short prose style effectively for his audience. But by 1850, Dickens had established himself as a major writer and he could afford to disparage his earlier work. Despite this, the situations, character types and stories from this book inform a reading of his later writings. Dickensian themes like poverty and debt, marriage and lawyers, are already present. There are also early intimations of later characters from his novels, like Bill Sikes in Oliver Twist (evident in the partner who beats his wife in ‘The Hospital Patient’), or even Mr Bumble from that same novel. Misanthropic men like Mr Dumps seem to anticipate Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, even if Dumps isn’t railing against Christmas. The issue of imprisonment for debt is also already present in a number of the sketches, just as it was to appear in The Pickwick Papers and other novels in Dickens’s career. In short, reading the Sketches isn’t only an opportunity to see the development of a great writer, but it’s a great insight into the world of 19th Century London, the setting of many of Dickens’s novels.

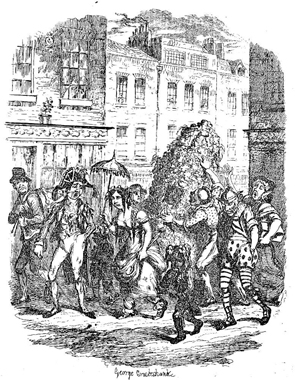

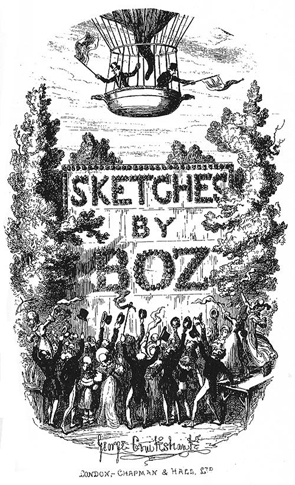

So I prefer Dickens’s earlier expression of hope for his work, rather than the older dismissive Dickens of 1850. In his preface to the first edition of the Sketches in 1836, he compares his work to a “pilot balloon, trusting it might catch a favourable current, and devoutly and earnestly hoping it may go off well.” He adds more emphatically, “it is very possible for a man to embark, not only himself, but all his hopes of future fame, and all his chances of future success.” It is a sentiment nicely captured by George Cruickshank’s George Cruickshank’s illustration for the front piece of the work, with two men waving flags from the basket of a hot air balloon (I like to presume one of them is Dickens, even though the scene is described in ‘Vauxhall-Gardens by Day’), as a crowd of well-wishers waves them off from below. As it turned out, Dickens’s hopes for his work were not unfounded. The Sketches helped Dickens secure the job of writing accompanying pieces for Robert Seymour’s series of illustrations around gentleman’s clubs and sporting endeavours, which evolved into Dickens’ first – and highly successful – novel, The Pickwick Papers (Dickens’s collaboration with Robert Seymour is discussed in my review for The Pickwick Papers).

These days Sketches by Boz is not as well-known as Dickens’s later writings. In fact, the edition I own was the first edition published by Penguin, as late as 1995. And given their interest in London life of the 1830s – the way they reflect concerns from that period – the Sketches may not be as appealing to some people, especially given that they are a collection of Dickens’s shorter writings, and somewhat underdeveloped compared to his novels. Dickens is content to establish a scene or situation and then just as quickly abandon it. “Years have elapsed since the occurrence of this dreadful morning” the narrator interjects at the climactic moment of ‘Horatio Sparkins’. “In short, the whole affair was, as Mrs Joseph Porter triumphantly told every body, ‘a complete failure’”, we are told at the end of ‘Mrs Joseph Porter’. In the longer pieces – typically the short stories in the last section, ‘Tales’ – Dickens is able to draw his reader into his narrative with all the skill typical of his later work. But his purpose is usually singular – to satirise institutional behaviour or social habits, or introduce us to a scene or a type – and once he has given us this quick sketch, a thumbnail of life, he as quickly abandons it before a reader can tire of the story.

I found the range of subjects and tone made reading the Sketches a pleasure. There are moments of high farce, such as the story of ‘The Great Winglebury Duel’, in which Mr Trott finds himself married to a woman whom he has never before met, after being challenged to a duel by a man he doesn’t know and incarcerated in a mental asylum on a pretence he has misunderstood. Somehow it all makes sense in the story and there is a great deal of pleasure in Dickens’s skilled manipulation of the plot. Even when his topic is specific to his time, like his discussion of Vauxhall Gardens, which had only just been made available to the public during the day, he manages to speak to truths that underlie our own experiences of life: the sense that the gardens are a disappointment during the day speaks to experiences of returning to a place in one’s past, or meeting someone again under different circumstances, which causes a re-evaluation, possibly disappointment. Yet, at other times, the scene is tragic: the death of an alcoholic and the impact of his addiction upon his whole family; or the domestic abuse of a woman, beaten so badly she dies, yet refuses to implicate her partner before she does. Dickens was incredibly popular from the very start of his career, and I attribute this largely to his ability to hold a mirror to the realities of peoples’ lives. Looking past the absurd names he often gave his characters, Dickens’s writing speaks to the realities of nineteenth century living. When he describes a prison, we know he has walked through its gates, and we know he understands the anguish of debt and the debtors’ prison, because his father was incarcerated for debt when he was young. When he speaks of the discomforts of travel, or the indignities of sexual competition for marriage, or the implacable and unsympathetic legal system, or the living conditions of the poor, we know he is giving us an insight into nineteenth century society and its concerns that would have been recognisable to his audience.

To that end, the Sketches are worth reading if you are interested in nineteenth century living conditions, or nineteenth century London society. They are also a good starting point if you are interested in reading nineteenth century fiction, particularly Dickens, for their broad perspective of that time and their anticipation of Dickens’s later work. But apart from that, I also found them fascinating because Dickens reveals a shared humanity with us. And it is not just because issues like domestic violence remain a concern, but because Dickens gives us the whole gamut of human experience. Just as it did in Dickens’s day, the pressures of family and marriage still affect us: we experience the sad longing of nostalgia and the feelings of threat inherent in change, as apparent in Dickens’s writing about disappearing traditions and characters within the city. And when Dickens describes the horrors of early morning travel, the loss of luggage or the disapproving stares of other passengers whose established seating arrangements are about to be disturbed by a newcomer, we sense our shared experience with people of the 1830s. When we read about the election for a new beadle, we recognise the political tricks and ploys described by Dickens because we are so used to them in our own lives. And anyone who loves Shakespeare is bound to have endured at least one terrible production. So the awful production of Othello, as described in ‘Mrs Joseph Porter’, is bound to make us smile. In short, when reading Sketches by Boz, there is a sense that while the conditions of people’s lives have improved and the kind of jobs they do have changed, human nature is pretty much as it was back in the 1830s. Which makes sense, otherwise novels from that time couldn’t speak to us the way they do.

So, I found the experience of reading Sketches by Boz enjoyable. Some people might choose to skip over the earlier sketches which are more descriptive and head straight to pieces which are more fictional. That will depend on what you’re hoping to get from them. What is beyond doubt is that there was a market for this writing in the 1830s, and it is clear that much of it would no longer be easily obtainable for the general reader, except that in this case the work is from a major writer. So Sketches by Boz offers that, too: an opportunity to read a genre of writing from this period now not easily obtained by modern readers.

An Overview of Sketches by Boz

(This overview is best viewed on a computer monitor)

SEVEN SKETCHES FROM OUR PARISH

The Beadle – The Parish Engine – The Schoolmaster

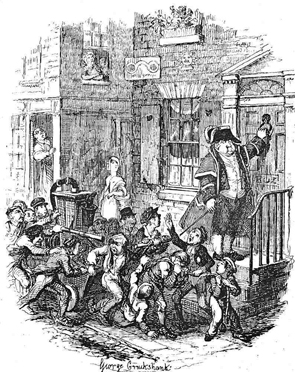

A descriptive piece about the roles of the three functionaries named in the title. The description of the Beadle and George Cruickshank's illustration (see the illustration to the right) are of particular interest, as they are good insights for those unfamiliar with this parish position, and they provide a good introduction to Mr Bumble from Oliver Twist.

The Curate – The Old Lady – The Half-pay Captain

Dickens personalises these sketches of parish functionaries more than the first sketch, adding some elements observed from life. The curate is a young clergyman who attracts the attention of the ladies. The old naval officer, unnamed in this piece, but later identified as Captain Purday in ‘The Election for Beadle’, is the old lady’s neighbour and does unexpected handy work, much of it poor. He also tends to stir trouble by challenging convention and putting himself forward.

The Four Sisters

The four sisters are the Miss Willises, near neighbours in Dickens’s portrait of a local parish, as are most in this section. All four Miss Willises seem doomed to remain spinsters, until Mr Robinson takes an interest in one of them. But which one? No one can work it out, not even on the wedding day!

The Election for Beadle

A hilarious account of an election for beadle after the old beadle dies. Each candidate seems to claim they are most eligible for the roll based on the number of children they have, resulting in a ridiculous escalation in the campaign, each candidate possessing more dependants than the last. That is until Mr Purday, the retired naval officer, upsets everything by backing Mr Bung, who only has ‘Five small children’. Mr Purday is first seen, unnamed, as the naval officer of the second sketch. He proves to be a greater strategist for Mr Bung than his opponents.

The Broker’s Man

Mr Bung, the recently elected beadle, tells of his earlier experience working for a Broker. Brokers took control of assets when people could no longer pay their debts. Mr Bung speaks about the wide range of experience, from the comical to the tragic, when he was required to live with the unfortunate debtors, sometimes for days, to prevent items of value being taken out of the house, before the debtors were evicted.

The Ladies’ Society

A funny story about various ladies’ societies, particularly the Prayer Book Distribution Society and the Children’s Examination Society, each becoming rivals for the hearts and minds of their charges.

Our Next-door Neighbour

What begins as a light essay about how door knockers reveal personality, ends with a family tragedy.

SCENES

The Streets – Morning

A description of London streets that come to life in the early morning, including a reference to spontaneous combustion, which was to later famously feature in Bleak House.

The Streets – Night

A description of London streets at night, including an account of a poor woman who tries to earn money by singing with her weak voice

Shops and Their Tenants

This sketch provides an account of the various failed businesses that have existed in one shop location; a look at the changing character of London.

Scotland-yard

An account of a small piece of waste land – not the modern police force – that is developed over time. Another look at the changing face of London

Seven Dials

The title refers to a poor part of London where seven streets meet at one central point. Here the people are so poor that several families will live in one house, each occupying a room.

Meditations in Monmouth-street

In Dickens’s day, Monmouth Street was an emporium for second-hand clothing stores. This is a description of the street and further speculations about what clothes can reveal about people.

Hackney-coach Stands

The London Hackney Carriage Act of 1831 fixed fares for London Hackney Coaches. Like the pressures on modern cab drivers with innovations like Uber and Lift, Dickens discusses the impact on the Hackney Coaches with the introduction of cabs and omnibuses into the city.

Doctors’ Commons

The ‘doctors’ of the title refers to Doctors of Law. This piece establishes Dickens’s attitudes towards the legal profession with a satirical jab at its customs and practices.

London Recreations

This piece considers the importance of private and public gardens for recreation, and the differences in class as related to the enjoyment of gardens.

The River

This piece anticipates a longer story in ‘Tales’, The Steam Excursion. Recreational boating is portrayed as miserable and embarrassing, while travelling by boat is fraught with troubles, in particular, losing one’s luggage.

Astley’s

Astley’s is a circus in London during Dickens’s period, and he describes the various acts, as well as a family who goes to see the show.

Greenwich Fair

Dickens describes the fair at Greenwich held during Easter; the stalls, fair games, fortune tellers, drama played so badly it is funny, and the freak show.

Private Theatres

Private Theatres were typically run with amateur actors who paid for the right to perform. Some did so for fun, others in the hope of being discovered. For this latter group, unscrupulous theatre managers would pretend there were talent scouts in the audience.

Vauxhall-gardens by Day

Vauxhill Gardens had long been a site for nocturnal fun, but were prohibited to the public during the day. When this rule is overturned, Dickens notes the magic of the night-time scene is diminished when it becomes apparent how poor and tawdry some of the sets and exhibits are by day.

Early Coaches

Dickens, a frequenter of long coach rides, describes the tortures of these journeys: booking the tickets, the early morning starts, their delays and discomforts.

Omnibuses

Omnibuses, used for short journeys in London, do not have the same disadvantages as long coach rides, but suffer from overcrowding and unscrupulous ride operators.

The Last Cab-driver, and the First Omnibus Cad

Tells the story of the changing character of London through the two characters of the story. The Last Cab driver, representing the old order, is put in prison after an altercation over a fair with a rude young man. The Omnibus Cad, William Barker, is the new breed, ripping customers off, and conducting his business disreputably.

A Parliamentary Sketch

Anecdotes about parliament, including the story of Nicholas, the butler.

Public Dinners

A description of public dinners in which the rich can gain notoriety by donating to the poor and to orphans.

The First of May

A description of the May Day parade, originally associated with the celebration of spring, in which chimney sweeps featured prominently. Dickens relates interesting myths about chimney sweeps, and laments the changing nature of the parades which seldom feature the boys, anymore.

Brokers’ and Marine-store Shops

A description of Brokers Shops, much like modern pawn shows, and the varying degrees of quality of their merchandise, depending upon the socio-economic group associated with them.

Gin-shops

Dickens describes the gentrification of gin shops, while at the same time the poor who frequent them are increasingly destitute and corrupted. Dickens refuses to blame the poor for their condition. Rather, he suggests a level of exploitation and immorality on the part of the gin shops.

The Pawnbroker’s Shop

Describes the goods available at pawn shops and the stigma attached to patronising them. Some pawn shops have secret entrances for this reason. Pawn shop owners are portrayed as exploitative and even violent.

Criminal Courts

Describes the terror of local prison, as well as the lack of compassion and sympathy from the law as it is conducted in the courts.

A Visit to Newgate

Dickens was given a tour of Newgate Gaol, and he describes the experience of walking through the various sections, all secured with bolted doors. He describes the boys’ school for young prisoners, the exercise yard, and the hopelessness of the condemned cells, where men await their executions.

CHARACTERS

Thoughts about People

Dickens reflects upon the lonely people of London, often seen in parks, as well as rich misanthropes who criticise other people and their lives.

A Christmas Dinner

Dickens reveals his hope for Christmas in this early piece; a time for reconciliation and family.

The New Year

Dickens describes the merriment of New Year through the character of Mr Tupple, as he drinks and toasts the old year out. Nevertheless, New Year is also a reminder of our approaching death; another milestone passed.

Miss Evans and the Eagle

This is a story of Samuel Wilkins who goes on a date with Jemima Evans to the Eagle, a popular tavern, where he almost gets into a fight when other men flirt with Jemima.

The Parlour Orator

A story about Mr Rogers who is verbally aggressive and believes he can destroy any argument by endlessly asking for more proof. Dickens sees him as a type who is contemptible because the extremes of his manner are not justified by his cause.

The Hospital Patient

A man is arrested for beating his wife so badly she has been taken to hospital. But when the magistrates take him to the hospital to be identified by his wife, she refuses to implicate him. She dies saying it was her fault: that she had had an accident.

Misplaced Attachment of Mr John Dounce

John Dounce is an old boy who is content with bachelorhood until he falls for a young girl working in an oyster shop. Dickens satirises Dounce’s vanity, and introduces a theme common to his work: the perils of marriage.

The Mistaken Milliner (A Tale of Ambition)

This story seems to expand on the story of the woman with a weak voice in ‘The Streets - Night’. Miss Amelia Martin sings at a party and is encouraged to take up singing professionally. But in the days before electronic microphones, her voice is not strong enough to project, and she abandons her ambitions.

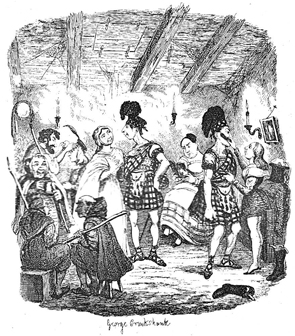

The Dancing Academy

This is the story of Augustus Copper who decides to break the monotony of his life by taking dancing lessons. Unfortunately, as he becomes more involved in dancing, Miss Billsmethi, one of the family of dance teachers, becomes more attached to him. When he denies having made promises of marriage, he is sued for breach of promise, much like Mr Pickwick in The Pickwick Papers.

Shabby-genteel People

Dickens writes about ‘shabby-genteel’ people: those who are down on their luck but strive to keep up appearances.

Making a Night of It

Mr Potter and Mr Roberts plan to ‘make a night of it’ – essentially what we would now call a pub crawl. They get drunk and then attend a theatre, where they disturb the audience and get thrown out. They next attend a wine vault where they carouse with others and get drunker. They awake the next day in a police cell, along with others from the wine vault, with most of their clothes missing.

The Prisoners’ Van

A short tale of two sisters being transported to prison. There is no longer much hope for the older sister, too hardened by her experiences. Sadly, while there is yet hope for the younger sister, she will almost inevitably follow the path of her sibling in a few years’ time.

TALES

The Boarding-house

Mrs Tibbs intends to establish a respectable boarding house, but how can she do this if her boarders all marry one another, or her husband has an affair with a servant, or she is falsely accused of romantic trysts herself?

Mr Minns and His Cousin

Mr and Mrs Budden invite their cousin, Mr Augustus Minns, to dinner in the hope that he might make Alexander, their son, his heir. But Mr Minns is a typical Dickensian misanthrope, and their efforts to please him are just as likely to have the opposite effect they desire. This story was originally published in December 1833 as was ‘A Dinner at Poplar Walk’, and was Dickens’s first ever published work.

Sentiment

Cornelius Dingwall, M.P., sends his daughter, Lavinia, to Miss Crumpton’s finishing school for girls, in order that she might be gotten away from a young man deemed socially unfit. Dingwall encourages Miss Crumpton to allow more suitable attachments to grow with other more suitable men while Lavinia is in her care, and the finishing school's ball might seem to be a good place for this to happen. But Lavinia is determined not to involve herself in the ball, until she meets Mr Neville Walter, the very young man she has been sent there to be gotten away from, who has assumed a false identiy.

The Tuggs’s at Ramsgate

The Tuggs family are green grocers who inherit money and decide to improve their social position with a move to the seaside at Ramsgate. But despite their pretensions, they are little more than innocents abroad, and they are prime targets to be ripped off.

Horatio Sparkins

Mr Malderton is nouveau riche and likes to adopt the airs of his social betters. His daughter, Teresa, is single, and so something must be done for her. The family invite Horatio Sparkins, a young man assumed to be in law, to dinner, in the hope of doing well by their daughter. But Malderton’s plans for Teresa are upset when it is discovered that Horatio Sparkins is not all he seems.

The Black Veil

A young woman arrives at a doctor’s house and asks that he attend someone who will be dead by morning. The doctor offers to attend the patient that night in the hope of saving him, but the woman refuses and says he can only attend the patient once he is dead. The doctor is horrified the next morning to discover he has been called in the hope of reviving the woman’s son, now dead from hanging.

The Steam Excursion

This story recalls Dickens’s shorter scene, The River. Percy Noakes proposes a party on a boat. Dickens satirises committees with the comical makeup of the committee to organise this outing, and adds further weight to his assertion that boat trips are torturous, when a storm hits the vessel and everyone is seasick.

The Great Winglebury Duel

This hilarious story recounts how Alexander Trott, in a case of mistaken identity and crossed purposes, is challenged to a duel, is incarcerated in an asylum, and yet manages to marry a young lady he has never before met without ever intending to.

Mrs Joseph Porter

This is another hilarious story about an amateur production of Othello in the house of Mr Gattleton, where everything that can go wrong does, yet everyone leaves in the early hours of the morning having been well entertained.

Passage in the Life of Mr Watkin’s Tottle

Watkins Tottle is a bachelor who decides he would like to marry. To this end, his friend, Gabriel Parsons, invites him to his house for dinner and to meet a morally strict spinster, Miss Lillerton. But the best part of the story is Gabriel Parson’s recount of his own wedding night, when he was trapped in a chimney as he hid from his new father-in-law.

The Bloomsbury Christening

Mr Nichodemus Dumps is a curmudgeon and misanthrope who dislikes children. But he is asked by his nephew, Charles Kitterbell, to be the godfather to his new son. Dumps actually goes to the effort of buying a christening mug for the child. But it is stolen from him before he arrives at the christening. After the service, Dumps takes great pleasure in meditating on the possible death of the child during his speech, much to the dismay of Mr and Mrs Kitterbell.

The Drunkard’s Death

A sad tale about the effects of alcohol, not just upon the individual, but the whole family, including their future prospects for prosperity and happiness.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!