Jeremy Tambling, who wrote the introduction for my Penguin Classics edition of David Copperfield, describes the novel as “a book for children almost”. At nearly 900 pages, this would seem a stretch, but I did struggle through it when I was about eleven or twelve. That was a long time ago, yet I still had vivid memories of the first half of the novel as I began to reread it all these years later, many accurate, some not. The second part of the novel was probably less appealing to my younger self. I knew as I reread David Copperfield that David would marry Agnes and that everything would work out well for the Micawbers, but when I read it as a child, I did not experience the same connection with the second half of the book as I did to the first part of the story when David is young, poor and powerless. I’m defining first and second halves fairly arbitrarily in my head. Let’s say that the second half begins at chapter 32, halfway through the chapter count and just after Emily has been discovered to have run away with Steerforth, although in my mind the first half of the novel is primarily defined by David’s childhood.

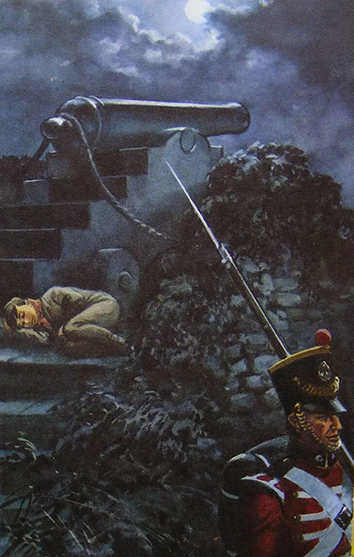

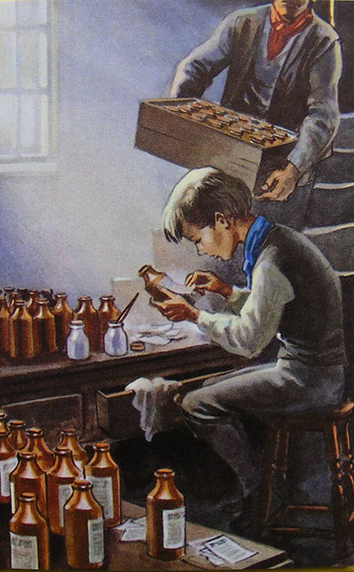

So at least parts of David Copperfield’s story have the potential to appeal to children. In fact, I think reading extracts from the book with a child would be a good way to introduce them to new, more sophisticated reading experiences. As a child I was originally drawn to the novel by a Ladybird book about Dickens I received. The first page of the book makes reference to David’s long walk to Dover to escape his life of servitude under Murdstone and Grinby, a company run by his stepfather, Edward Murdstone, and describes how he sleeps beneath a cannon during his journey. On the second page, the book tells the story of Dickens’ work in the Warren Blacking Factory when he was twelve. These details and their accompanying illustrations sparked my imagination. All these years later, the plight of David’s life under the Murdstones and the kindnesses shown to him by the Peggotty family, the Micawbers and his aunt, speak deeply to me of human nature.

My own feelings about the novel are tied to this long association and the impact it had upon me when young. Even now, I love the novel, regardless of any observations I make throughout this review. Because the novel is so expansive and there has been so much written about David Copperfield since its publication, I have decided to make the focus of this review narrow, pertaining to my personal thoughts while rereading it. For anyone familiar with the novel who feels I have neglected some of its best parts or have been too selective, I apologise in advance. David Copperfield is a great novel, but this review is written as a response to a question that occurred to me as I read and could not shake from my mind.

David’s Early Life

Even for Dickens, David Copperfield was his most beloved novel of those he wrote. In his preface for the 1867 reprint of David Copperfield, Charles Dickens ended with the following remark:

Of all my books, I like this the best. It will be easily believed that I am a fond parent to every child of my fancy, and that no one can ever love that family as dearly as I love them. But, like many fond parents, I have in my heart of hearts a favourite child. And his name is DAVID COPPERFIELD.

This is one of the best-known things about David Copperfield: that Dickens claimed the novel as a favourite child, partly because it spoke so strongly of his own experiences. His statement means any interest in the novel’s autobiographical elements is usually focussed on the early part of David’s story. As in Dickens’ own childhood, young David Copperfield suffers poverty and setbacks, but through his talent he is eventually able to overcome adversity. There are other obvious allusions to be made about Dickens’ adult life, like David learning stenography and reporting parliamentary speeches before undertaking a successful writing career. But it is the details of poverty that draw most attention. Young David recalls to our mind little Oliver from Oliver Twist, and Dickens’ later character, Pip from Great Expectations, another orphan, all of whom are vulnerable and tug our heartstrings. Children in Dickens’ novels are at the mercy of overbearing parental figures, suffer the cruelties of the English school system or the vagaries of workhouses and orphanages. This is how Dickens’ work is characterised in popular culture. It is little wonder, when we think of David Copperfield, that we think of him in his workhouse pasting labels or the humiliation of wearing the placard, “He bites”, rather than his later, successful career.

And it is easier to discuss these elements because this is what Dickens was most moved to speak about with his friend and biographer, John Forster. David’s mother, Clara, has remarried early in the story to Mr Murdstone. Murdstone, whose name Dickens intentionally hoped would evoke ‘murder’ in the reader’s mind, has taken control of his mother’s life with the help of his sister, Jane. When Clara dies, Mr Murdstone has little interest in David and does not wish to support him financially. He sets him to work at Murdstone and Grinby, his own business, which, among other things, supplies wine and spirits to packet ships. David describes how he cleans bottles, pastes labels to them, and when they are full, packs them for shipping. It is no accident that David’s menial occupation should so resemble Dicken’s own job at Warren’s Blacking Factory in London when he was a boy. Dickens’ family was under financial stress and his father was arrested and put in Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison when Dickens was twelve. Dickens’ mother and his youngest siblings joined him in prison. Dickens was forced upon his own resources, taking work at the Factory to pay for his own food and needs each week. He visited his family in prison during weekends. This was in 1824. Dickens was so pained by the experience that he never revealed the details to anyone until 1847 when John Forster asked about an acquaintance who remembered him. This conversation occurred before Dickens had the idea for David Copperfield. The book’s serialisation began in 1848 and finished in 1850, when it was then published as a single volume.

Unlike Dickens’ father, David’s has already died by the time his story begins. But the demoralising situation at Murdstone and Grinby’s is clearly a representation of Dickens’ own. The truth of this can be seen in an autobiography Dickens had been writing, which he soon abandoned in favour of his novel. Forster quotes from it in his biography to demonstrate the sense of despair young Dickens felt for his own prospects:

It is wonderful to me how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age. It is wonderful to me, that, even after my descent into the poor little drudge I had been since we came to London, no one had compassion enough on me – a child of singular abilities, quick, eager, delicate, and soon hurt, bodily or mentally – to suggest that something might have been spared, as certainly it might have been, to place me at any common school.

John Forster, The Life of Charles Dickens Vol.1 1812-1842, Chapter 2. (The biography can be read on Gutenberg by

clicking here).

Dickens’ choice of ‘wonderful’ is not sarcastic, but used to suggest bewilderment. Mindful of his own talents, even as a young boy, Dickens despaired at the prospect of ever receiving an education again. He later expressed his sense of isolation to Forster – how he missed the friendship of boys his own age – and he was made painfully aware of his own lost opportunities, highlighted by the success of his sister, Fanny, at the Royal Academy of Music. When Dickens brings David to the point that he must work at Murdstone’s warehouse, he has David express similarly gloomy thoughts:

The deep remembrance of the sense I had, of being utterly without hope now; of the shame I felt in my position; of the misery it was to my young heart to believe that day by day what I had learned, and thought, and delighted in, and raised my fancy and my emulation up by, would pass away from me, little by little, never to be brought back anymore, cannot be written.

Mr Micawber doesn’t enter the story until David is working for Murderstone and Grinby because Mr Quinion, who manages Murdstone’s business, lodges David with the Micawbers. It is here that Dickens reconciles the circumstances of the plot even more closely with his own life. Immediately, we are aware that the Micawbers are in financial difficulties. “The only visitors I ever saw or heard of, were creditors”, David tells us. Creditors pound aggressively upon Micawber’s door. David writes, “At these times, Mr Micawber would be transported with grief and mortification.” He would also contemplate suicide. But Micawber is capable of polarised emotions which might contribute to his financial stresses. Having only just threatened to kill himself, he might then be seen leaving the house a short time later, “humming a tune with a greater air of gentility than ever”. David describes these wildly varying emotions as “elastic”. What is clear is that Mr Micawber is a representation of Dickens’ own father. Micawber asks David to help him sell household items to cover his debts, but when things reach a critical point Micawber is arrested for debt and taken to King’s Bench Prison where David visits him.

Given the strong associations with events in Dickens’ life, it is not surprising that David Copperfield was the first novel Dickens wrote entirely from a first-person perspective. He’d experimented with first person narration at the beginning of The Old Curiosity Shop, one of two novels he serialised in his magazine, Master Humphrey’s Clock. Master Humphrey, himself, narrates the first three chapters of that novel, thereby forming a narrative bridge between the fictional premise of the magazine and the story, itself.

Marriage

David Copperfield is the life story of David, written from his perspective many years later when he is happily married with children and he has become a successful novelist. If the first part of the book is about David growing up and working his way out of poverty, the second half is largely about marriages, and their import upon social status and moral reputation. David marries the angelic Agnes in a fairytale denouement. But David’s path to Agnes may just as easily reflect upon Dickens’ own struggles with his marriage, I realised, as I reread the novel. I found that to be a tantalising thought. The degree to which a connection between writers and their work can be made is always questionable, but Dickens’ close association with the novel and its eponymous protagonist has always drawn this kind of analysis.

Dickens conceived of his novels as his children, although he also had ten children with Catherine Hogarth during their 22-year-long marriage, and as I thought about David’s story I was also thinking about Dickens’ own unhappy marriage. One of their children, Dora, was born three months before David Copperfield’s serialisation ended, and died only seven months old in April 1851. Dicken’s couldn’t know this would happen when he wrote the death scene for Dora’s namesake in David Copperfield, David’s first wife whom he pursues with a passion. But as he faces the realities of marriage with Dora, David comes to feel that “the happiness I had vaguely anticipated, once, was not the happiness I enjoyed, and there was always something wanting.” By the time Dora is dying David continues to harbour his secret feeling that his affection for Dora is waning. As he carries her upstairs to their bedroom he acknowledges,

A dead blank feeling came upon me, as if I were approaching to some frozen region yet unseen, that numbed my life. I avoided the recognition of this feeling by any name, or by any communing with myself; until one night, when it was very strong upon me, and my aunt had left her with a parting cry of ‘Good night, Little Blossom’, I sat down at my desk alone, and cried to think, O what a fatal name it was, and how the blossom withered in its bloom upon the tree!

It’s a satisfyingly ambiguous statement, since the dying bloom is both Dora’s withering physical health as well David’s diminishing feelings for her. Dickens often conflates death with a higher spiritual meaning, or allows a death to take on a symbolic import. Dora’s death scene occurs offstage, so to speak. She dies upstairs with Agnes in attendance while David sits downstairs with his wife’s dog, Jip. Jip has been full of life from the moment we first meet him, but he physically declines because of his age, in tandem with Dora’s declining health. When Dora dies upstairs with Agnes in attendance, David is downstairs with Jip, who dies in front of him at the same moment. It is the kind of contrived sentimentality that modern audiences may find less appealing in Dickens, like the death scene of Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop. But in this case, through the sentimentality and the symbolism of the dog’s death, we sense that David’s separation from Dora at this moment is more than physical. The heightened emotion of the scene is moderated by the reality of the feelings with which David struggles:

I sit by the fire, thinking with a blind remorse of all those secret feelings I have nourished since my marriage. I think of every little trifle between me and Dora, and feel the truth, that trifles make the sum of life.

David’s feelings for Dora, as all-encompassing as they had been when he courted her, have been withered by her want of intellectual and practical qualities as a wife. Dora can neither handle the servants, nor can she run the household effectively. David has attempted to engage with Dora in his work, but the best he has achieved is to have her hold his pens and to do some copying. David’s aunt Betsey wisely rejects his suggestion that she might offer Dora advice. David, less sagacious, enters upon a short-lived project, “to form Dora’s mind”. He speaks with her about intellectual subjects that are of interest to him and reads her Shakespeare. David wants Dora to mature into a woman while Dora asks him to call her “child-wife”, in deference to the happier times of their youth. Long before David admits his feelings to us, Dora feels insecure about Agnes, David’s friend since childhood, not as a sexual rival but for the light she shines upon Dora’s deficiencies. Dora understands the intellectual attraction Agnes offers: “If I had had her for a friend a long time ago … I might have been more clever perhaps?” she says to David. For his part, David is somewhat circumspect about his feelings for Agnes with the reader. He admits long after Dora has died, “I have desired to keep the most secret current of my mind apart” and claims he cannot detail at what point his affections for Agnes changed from brotherly love to something deeper. We understand his feelings for Dora change before her death, but he can’t – or won’t – recall when his feelings for Agnes changed.

Dickens’ Marriage Crisis

What Forster could not have contemplated when he spoke to Dickens about the Blacking Factory – what Dickens would never have revealed – is the state of his feelings for his own wife, Catherine, during the period preceding the writing of the novel. What the actual state of the marriage was in 1850 when Dickens was concluding his serialisation of David Copperfield, we can only speculate. But speculation and later events do allow for a fairly convincing argument that Dickens was already unhappy. At this time Dickens’ marriage to Catherine Hogarth was in its fifteenth year. He would annul the marriage in 1858, claiming that his wife was mentally unstable and unsuitable. He claimed she was depressed, that she was a poor housekeeper and she made it difficult for him to work. Some of the accusations he made publicly against Catherine find similar expression in the haunted secret of David’s waning affections for Dora.

In a letter Dickens sent to his agent, Arthur Smith, (now known as ‘The Violated Letter’), Dickens was eager to portray Catherine as the instigator of the separation: “For some past years Mrs Dickens has been in the habit of representing to me that it would be better for her to go away and live apart.” For Dickens’ part, he claimed, “I have uniformly replied that we must bear our misfortune, and fight the fight out to the end; that the children were the first consideration, and that I feared they must bind us together ‘in appearance’.” Furthermore, Dickens took pains to relieve his sister-in-law, Georgina, who lived with Dickens and his wife, of any blame. He stated that Georgina had not only devoted her youth to their children – a swipe at Catherine as a mother, perhaps – but had “suffered and toiled, again and again to prevent a separation between Mrs Dickens and me.” Dickens told Smith in a note accompanying his letter, “You have not only my full permission to show this, but I beg you to show, to any one who wishes to do me right, or to any one who may have been misled into doing me wrong.” Dickens knew the power of his words, and his letter to Smith was intended to represent him publicly and inoculate his reputation. The letter soon went public, although Dickens’ reputation suffered from public scrutiny: the story became an international sensation.

But the facts of the matter were somewhat different than Dickens represented them. Later correspondence reveals Dickens to have been cruel to his wife. He even tried to have her committed to a mental asylum. And he is somewhat circumspect about the reasons for the separation. He claims that despite his commitment to the marriage, it was John Forster who recommended the separation for the sake of the children. But Dickens also mentions “a young lady” towards the end of the letter: “I will not repeat her name – I honor it too much.” The young lady in question was Ellen Ternan, an 18-year-old actress with whom Dickens most likely had an affair. Naturally, Dickens denied this in public. That year he published an article in his magazine, Household Words, in which he denied rumours about the affair, calling them “abominably false”.

Nevertheless, just to set the record straight, Catherine Hogarth was not insane. She was intelligent and published a book of her own. She was a talented actress. In 2014 a University of York professor, John Bowen, found a collection of 98 previously unseen letters written by Edward Cook, a friend of Dickens’ family, to a fellow journalist, who, in one letter wrote:

He [Charles] discovered at last that she had outgrown his liking. She had borne 10 children and had lost many of her good looks, was growing old, in fact. He even tried to shut her up in a lunatic asylum, poor thing! But bad as the law is in regard to proof of insanity he could not quite wrest it to his purpose.

While the rumours of Dickens’ infidelities rose to a head in 1858, they long predate his separation with his wife. Georgina, his sister-in-law, who had lived with Dickens and Catherine since 1842, is believed to have had a relationship with Dickens, too. His fervent desire to protect her reputation in his letter to Smith only adds to that suspicion in my mind. In 1846 Dickens published The Battle of Life, the fourth of his five Christmas books, which told the story of his protagonist’s love for his wife, Marion, and her sister, Grace. It is only suggestive but it is of interest. And Dickens is said to have been infatuated with Mary Hogarth, his wife’s other sister, who also lived with them until her death in 1837. She died in Dickens’ arms. She has been idealised in some of Dickens’ characters, like Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop and even Agnes in David Copperfield. The fact is, if Dickens’ commitment to his marriage was already wavering prior to 1850, he would not have told Forster, as his efforts to spin the problem in 1858 show.

When the scandal broke in 1858 public focus turned to Dickens’ earlier novel Dombey and Son (1848) which dramatizes an emotionally abusive marriage. Newspapers ran stories about the separation with pointed references to Dickens’ earlier novel, suggesting that it was apropos, or that it anticipated the failure of Dickens’ marriage. The details of this can be read in an essay published on The Victorian Web website.

Dombey and Son was published two years before David Copperfield and ten years before the failure of Dickens’ own marriage with Catherine Hogarth. Yet the connection was already being made by the press and in academic circles of the time. It is interesting to speculate about Dickens’ much more mellow, more sentimentally received “child”, David Copperfield, as an expression of the same inner turmoil that must surely have already visited Dickens’ thoughts by this stage.

In 1858 Dickens didn’t get a divorce – his public profile made this difficult and inadvisable – but he separated from Catherine through a legal deed. After their estrangement became public knowledge Dickens wrote in another letter to Angela Burdett-Coutts, a long-time friend and confidante (to whom he dedicated Martin Chuzzlewit):

I believe my marriage has been for years and years as miserable a one as ever was made ... I believe that no two people were ever created with such an impossibility of interest, sympathy, confidence, sentiment, tender union of any kind between them as there is between my wife and me ...

The ‘Hero’ of David’s Story

It's a long digression to make on this subject when the separation happened eight years after David Copperfield was published, but it is tantalising to speculate about the state of the marriage prior to Dickens beginning to write his novel. The opening lines of the novel famously read: “Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.” There is a strange ambivalence in this opening. Already, it seems, David is uncertain of the judgment that will be made of him. That a sense of uncertainty should be more a part of David’s life as a child than his life as a successful writer, seems evident. Written from the perspective of an older, successful David, the uncertainty becomes interesting, as though he is unsure of the judgment of his reader.

But who else is to be the hero of David’s story, if not David? Is it aunt Betsey, who takes David in to protect him from the cruelty of Edward Murdstone and his sister; who gives him an education and a professional start in life? Is it the hapless Wilkins Micawber, who is constantly in debt but is kind to David and ultimately saves Agnes and her father from the machinations of Uriah Heep? Is it Ham, who stoically continues to work after he loses Emily to Steerforth, and later loses his life trying to save Steerforth and others from a sinking ship? Or is Mr Peggotty, an honest fisherman who takes David into his blended family, a hero for his unwavering commitment to bring Emily home and to love her regardless of what rumours stir after her elopement with Steerforth? Equally, are we to admire Tom Traddles, David’s friend from school, who becomes a lawyer and marries Sophy, for his unselfish devotion to Sophy’s sisters and his personal sacrifice to help raise them because their mother is incapacitated? Does this make him a hero?

The fact of it is there are several selfless characters who contribute to the wellbeing of others in this novel. But if this is the measure of heroism in this story, it is hard to apply the appellation to David. David often lacks insight. He does not see into Steerforth’s true character, as Agnes does, and he fails to see beyond the superficial attractions of Dora. Added to that, while David may be treated awfully as a child, and we rightly desire to see him succeed, David’s internal energies are directed unwaveringly to his own rising in the world. In chapter 42 he lists the personal qualities which he attributes to his success:

I never could have done, without the habits of punctuality, order, and diligence, without the determination to concentrate myself on one object at a time, no matter how quickly its successor should come upon its heels, which I then formed.

David is focussed upon success and his star rises from one job to another: from trainee proctor, to stenographer and court reporter, and finally as a successful novelist. Much of his success is driven by his desire to win Dora for himself. Through the course of the novel his affections are attached to a series of girls and women: his early love of Emily for whom he makes no serious advance; his infatuation with Miss Shepherd for whom he takes too long to make his move; his overpowering desire for Dora; and his final, more refined desire for Agnes.

On the question of David’s status within the story – a question raised by his own opening line – we might in turn ask: how would our assessment of David’s character be different if Dora had not died?

This is the question that niggled at me as I reread the novel.

Dora’s decline and death are portrayed as a physical manifestation of David’s own declining and dying love; as purely a convenient narrative device, one might argue. As the narrator, David’s portrayal of this key event speaks to a level of solipsism that is difficult to reconcile with his journey as the hero on his journey to the final apotheosis of love: Agnes.

Could David have remained married to Dora had she lived? Her surviving would have changed everything about the story and the characters. David would be faced with the prospect of living an unhappy lie, or instead playing out the drama that engulfed Dickens’ own life only eight years after the novel was published: a separation. In that scenario he would be more like Steerforth than Traddles. And how would such a separation have changed our perception of Agnes? In chapter 60 David tells Agnes that she was “ever leading me to something better; ever directing me to higher things!” Agnes, he says, is “a star above me, was brighter and higher” and he pictures her as saintlike, “Ever pointing upward”. Would the angelic Agnes have accepted David after his marriage failed, especially as she might be implicated in its failure? It seems unlikely, or she is not the woman David imagines.

It never occurred to me when I first read David Copperfield how many marriages there are in the story and how status and character are so often conferred by marriage. There is no shortage of bad marriages for a start, or relationships that fail to even make it to the altar. David’s aunt Betsey has had an unhappy marriage before David comes to live with her. Her husband had been younger than her, ill-tempered and violent. We are told in chapter 1, “These evidences of an incompatibility of temper induced Miss Betsey to pay him off, and effect a separation by mutual consent.” Now, living single, aunt Betsey encourages her maidservants to renounce men, though not to great success.

These so-called ‘bad’ marriages are often associated with considerations of class and wealth. The Peggotty family, living in their adapted boat on the shores of Yarmouth, are a blended family whose relationships have coalesced through a series of tragedies, mostly drownings since they are a fishing family. But they lead happy and respectable lives. They are a working-class family who seem untainted in their working-class simplicity. But Emily, who is the daughter of Mr Peggotty’s drowned brother-in-law, feels the limitations of her class, and desires to be a lady. Ill-natured stories circulate about her because of this aspiration, and it is evident that she is repelled by the thought of marrying the good-natured, honest Ham, whose prospects will always be tied to fishing. Emily’s ambitions make her prey to the charms of Steerforth, David’s old protector from school, whose class and personal charms make him an attractive prospect for her. But Emily’s story is the story of many working-class girls of the time who possess physical charms. Later, after her reputation is ruined by her elopement with Steerforth, Mr Littimer, Steerforth’s servant, reveals that Steerforth is repelled by Emily’s social class: “that she had told the children she was a boatman’s daughter, and that in her own country, long ago, she had roamed the beach, like them.” Steerforth’s mother makes the matter plain to Mr Peggotty. There will be no marriage to fix what has been done: “You cannot fail to know that she is far below him,” she says. “She is uneducated and ignorant.” Likewise, the unhappy Miss Dartle, who remains Mrs Steerforth’s unpaid companion, wastes her youth hoping that Steerforth will choose her. All she has received is a scar on her lip through his careless use of her, and she seems just as ruined as Emily, though she clings vainly to a sense of her own superiority.

The desire for wealth and status warps marriages in this novel. The oleaginous Uriah Heep is driven by a deep-seated class resentment that has twisted his personality into a false and fawning underling who claims to be humble, but who intends to overturn the economic and class limitations under which he exists. His twisted character is realised in his physical writhing, his cadaverous face and his clammy hands. He expresses his bitter feelings about class to David, almost as a confidence, once he feels assured that David is not sexual competition for Agnes:

We was to be umble to this person, and umble to that; and to pull off our caps here, and to make bows there; and always to know our place, and abase ourselves before our betters. And we had such a lot of betters! … ‘People like to be above you,’ says father, ‘keep yourself down.’ I am umble to the present moment, Master Copperfield, but I’ve got a little power!

Uriah intends to supplant Mr Wickfield, Agnes’ father, from his own legal practice, and eventually he intends to corner Agnes into a marriage with him that will annul the sense of social inferiority that has plagued him since birth. Agnes sees the evil of Uriah’s slow annexation of her father’s business: “He has mastered papa’s weaknesses, fostered them, and taken advantage of them, until … papa is afraid of him.” Uriah is a villain who intends to usurp and control. If you want a modern example of Uriah Heep, it is the character Wormtongue from The Lord of the Rings, whispering into King Theoden’s ear and reducing him to a puppet.

It’s a situation we have already seen earlier in the novel. Edward Murdstone courts David’s mother and marries her, and then proceeds to break her spirit until he has control of her life and finances. Later, when David meets his old family doctor, Mr Chillup, he is told that Murdstone has married again: “… her spirit has been entirely broken since her marriage,” Chillup tells David of Murdstone’s latest wife; “the brother and sister between them have nearly reduced her to a state of imbecility.”

The more successful marriages in the book are characterised by love and selflessness. Traddles long anticipates his marriage with Sophy and devotes his professional life to achieving a level of independence which will allow him to support her. David finds Traddles living in a Veterinary College at Camden Town, described as having an air of “faded gentility”. Traddles and Sophy live with Sophy’s sisters, Caroline, Sarah, Margaret, Lucy and Louisa, since Sophy’s mother is incapacitated and incapable of looking after them all the time. Traddles says he and Sophy are, “two of the happiest people”, and describes their life of limited economic means as one of simple pleasures taken at opportunity: of walks, and window shopping and happy imaginings of their future. Their pleasures, Traddles says, “are inexpensive, but they are quite wonderful.” Traddles is a selfless man who takes on the responsibility of Sophy’s sisters as a joy rather than a duty, and is sorry at the prospect of their leaving.

Dickens explores a whole series of marriages and relationships throughout the novel, like a study of the institution and its relationship with class, status and wealth. But the crowning glory is David’s final marriage with Agnes. Yet to elevate this marriage he must stand it atop a series of relationships and desires that either never come to fruition or fail. That Dickens might never have written Dora into the story is evident. But had he not, he would not have needed to dramatize the challenges faced by one of the most idealised marriages of the novel, either. Annie Markleham is the only woman in the novel who attains the same purity of character as Agnes, and it is her example that causes David to feel unhappy with Dora; that helps to reorientate his feelings towards Agnes. In this respect, the novel not only draws from the picaresque tradition, but from morality tales like Pilgrim’s Progress, in which the hero journeys towards a more perfect union with God and their own morality.

Annie Markleham marries Dr Strong, David’s old headmaster from Canterbury. There is a substantial age gap. Strong appears to be in his declining years, while it is supposed that Annie’s feelings truly lie with her young cousin, Jack Maldon, with whom she grew up. Annie’s mother, Mrs Markleham, expects that her daughter will exploit the hold she must surely have over her older husband, and implicitly suggests she might satisfy her more youthful urges with her cousin. Indeed, as readers, we are misdirected by Dickens to believe in an affair, primarily because David and Mr Wickfield believe in it, too. Uriah Heep will seek to expose Annie so that he can separate Agnes from the reputational loss he feels sure she will suffer, otherwise. Annie, having married without money, is presumed to have made a marriage of convenience. But contrary to her mother’s intentions, Annie refuses to exploit her husband. When her supposed affair is finally made public, Annie speaks of the quality of her love for her husband in a sincere speech: of how affection was first inspired by Strong’s friendship with her dead father, but that it grew into true affection. Annie rejects the notion that she might ever have been interested in Maldon as a husband. Rather, she was happy to have settled that speculation when she married Strong:

I might have come to persuade myself that I really loved him, and might have married him, and been most wretched. There can be no disparity in marriage like unsuitability of mind and purpose.

It is this last sentence that resounds in David’s thoughts: “There can be no disparity in marriage like unsuitability of mind and purpose.”

It is the first seed of doubt planted in David’s mind against his marriage with Dora, and it seems an eerie presentiment of the feelings Dickens expressed against his own wife eight years later when his marriage failed, after “years and years” of misery, according to him.

Approaching David Copperfield in this way reduces it, somewhat, to mining the text for evidence of Dickens’ thoughts about his life. I’m aware of that. But it is a response I make from honest curiosity, now I have read the novel anew. There is a fascinating parallel between David who writes his story, knowing what is in store for him and is able to control the representations of his own life through his narrative, and the author who may have well been struggling with his own feelings about his marriage as he wrote, without any idea how his dilemma might be resolved. Characters like Emily and Uriah Heep who desire more have little scope for dignity or happiness. But Dickens provides David with an elevating path that is sanctioned by a dying wife.

If you have come to this review to find out something about David Copperfield without having first read it, I recommend you read it, though it is a long novel that requires commitment. Even so, it is not a burden to read, and despite my musings, David is a sympathetic character whom we wish to see succeed. If you have come to this review as someone familiar with the book and think that the novel should be understood by some other metric or treated more generously, you are right in thinking that the novel has so much more to offer: whether it be as an insight into the working class of the 19th century; or how it gives us insight into the changing social and economic pressures that were shaping lives; or as an insight into the legal world and prisons of the 19th century (Dickens writes about visiting one in Sketches by Boz which seems to be the inspiration for the scene in which David finds Uriah Heep during a prison tour); or the social status of women during this period and the limited economic opportunities available to them; or the influence of the picaresque tradition and authors like Henry Fielding on Dickens; or simply as part of the development of the realist novel. There is so much more to say. One of my enduring memories of the novel from my reading of it as a child were the wonderful characters of Mr Micawber, and Mr Dick and his kites. Merely studying Dickens’ characters and the way he constructed them – sometimes as caricatures, sometimes as fully fleshed people – would be rewarding. Maybe you would just like to enjoy it as a good read. It is that.

But let’s return to that moment when Dora dies in her bedroom before I finish. Dora calls Agnes to her room although David does not know what she wishes to speak to Agnes about. David is downstairs with the dog. Many years after they are married, Agnes reveals that Dora had wanted Agnes to marry David after her death: “That only I would occupy this vacant place.” In fact, David has already imagined that “the spirit of my child-wife looked upon me, saying it was well”. Dora may not have had Agnes’ smarts, but she saw where things lay. Unfortunately, for Dickens, his own wife did not have the good grace to do the same. That’s harsh, I know, but the thought adds an interesting edge to reading this most beloved of Dickens’ novels, of a fairytale rags to riches story in which the ‘hero’ of the story gets the girl he deserves.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!