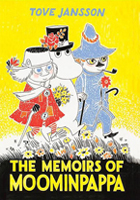

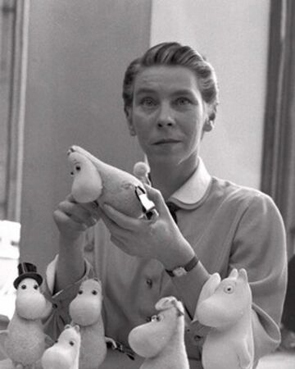

The Moomin Series #4

- Reviewed by: bikerbuddy

- Translator: Thomas Warburton

- Category:Children's Fiction

- Date Read:15 April 2021

- Pages:208

- Published:1994 (Revised English Edition)

This is the first Moomin novel (excluding The Moomins and the Great Flood, a shorter story) I am reviewing that I never read as a child. It was always out of stock, but a friend whom I introduced to the Moomins had it and I was always mildly envious. Back then, the English edition of the book was called The Exploits of Moominpappa, and my friend would have been reading the original version of this story which I don’t have access to. Jansson revised the book extensively in 1968, adding a prologue and new episodes. But the English translation of the new version, now known as The Memoirs of Moominpappa was not published until 1994. By that stage childhood was well in the past.

Moominpappa’s memoirs are a new approach to the world of the Moomins. It’s a generational change, in which Moominpappa, for the first time, takes centre stage in the story – he has always been a somewhat marginal character until now – and tells of his growing up and his adventurous spirit. In telling his story he also introduces us to Hodgkins, a ship owner and inventor, as well as the Muddler and his button collection, and the Joxter with his anti-establishment mindset and disinterest in owning or doing anything. The Muddler and the Joxter are fathers to Sniff and Snufkin, respectively. Moominpappa also introduces us to one of the most hilarious characters in the Moomin world so far, Edward the Booble, a creature so large that he is able to dam a river if he sits in it. Edward the Booble has a tendency to accidently squash people, but we feel he is well meaning, since he pays for the funerals. Unfortunately, Edward the Booble has run out of money, and is getting a little agitated about the prospect of squashing anyone else.

Jansson’s 1968 prologue wonderfully anticipates Moominpappa’s character and gives a humorous context for his memoirs. Moominpappa has been laid low by a cold and sore throat. He asks Moominmama to fetch Moomintroll, Sniff and Snufkin to his bed. He then tells them never to forget that they had had the privilege of spending their early lives in the company of a genuine adventurer

. This vignette tells us almost all we need to know about Moominpappa: he is vain, self-important and insecure. His incapacity and his domestic security seem to belie his pretensions of an adventurous spirit. And he is handled by Moominmamma like a troubled child. When no-one seems to understand the import of the meerschaum tram, a drawing room decoration (Moominmamma dismisses it as a lottery prize) he quails at the thought that he might die and no one would know his story or understand the significance of his life. Moominmamma hands him an exercise book and encourages him to write his memoirs. He does, and his reading the story to his family, interspersed with their reactions to it, are the basis of this book.

This book is charming and funny, and much of that comes from Moominpappa’s first person narration. He cannot help revealing more about himself than he should, and humanises the foibles of fathers for his readers:

You, innocent little child, who thinks your father is a dignified and serious person, when you read this story of three fathers’ adventures you should bear in mind that one pappa is very like another (at least when young).

His strong sense of self-worth and self-importance is cumulative: I’ve achieved quite a lot of good things

he tells us; That must have been because of my inherited ability but also because of talent, sound judgment and self-criticism

he reasons; This special talent must be inborn

; and I wouldn’t be surprised if my swaddling clothes had been embroidered with a royal crown

. When asked by Sniff and Snufkin to hear more about their own fathers, Moominpappa tells them, Your old fathers are simply so much background

. But Moominpappa is also creature fighting self-doubt. When he first looks into a mirror, he discovers that his paws are too small, helpless and childish. And his own sense of self does not find its equal in the world: Alas, there was no one besides myself who found me interesting

q> he laments. He is also not beyond self-pity: Oh, how sorry I felt for myself!

And he must overcome his desire for a sedentary, safe life to fulfil his self-conception as an adventurer: Is it possible for a house owner to be an adventurer?

he asks. When Moominpappa and his friends colonise an island (they hardly understand what a colony is) he becomes morose and bored: I began to feel almost contented. I felt such a colossal pity for myself.

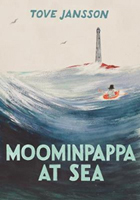

In Moominpappa’s memoirs we see a youthful character, full of hope, determination and drive. But his writing also anticipates the older Moominpappa of Moominpappa at Sea, who once more retires to an island with a lighthouse, except this time it is because he lacks purpose and joy in his life as his family grows. The two books capture him at these two different junctures in his life.

Jansson’s writing is skilful and subtle, as always, even if Moominpappa’s pronouncements of his own talents sometimes border on the braggadocios. Yet he is balanced nicely by the even-keeled Moominmamma who is sensible enough to support his writing but tell him the truth. When Moominpappa expresses doubts about the more sombre aspects of his memoir – the ‘Crisis of my Youth’ – Moominmamma understands the importance of Moominpappa recording his doubts, suggesting that it reveals a more rounded and interesting character: Everything’ll be much more vivid if you have some passages where you aren’t bragging

, she tell him.

But Moominpappa’s character is also defined by the characters who surround him. Far from being an individual talent and extraordinary adventurer, Moominpappa’s conflicted character can be seen in the ineptitude of the Muddler, as well as the grim Hattifatteners, a race of silent creatures who draw energy from storms, who constantly roam the earth seeking its horizon, whom Moominpappa pointedly refuses to write about. But it is the Joxter who unsettles Moominpappa, unconcerned as he is with doing or having. Hodgkin’s suggests, despite Moominpappa’s doubts, that the Joxter does take an interest in his world, but his relationship with it is not the same as theirs: For ourselves there is always one single interest,

he tells Moominpappa. You want to become. I want to do. My nephew wants to have. But the Joxster just lives.

The Joxster represents a philosophical tranquility that eludes Moominpappa, and for which he will continue to search in Moominpappa at Sea.

In The Memoirs of Moominpappa we are given an insight into Moominpappa’s later insecurities and dissatisfactions. It is also an entertaining and funny backstory, not only for Moominpappa, but Sniff and Snufkin, whose father’s share in Moominpappa’s adventures, and the first meeting of Moominpappa and Moominmamma, a thrilling adventure in itself. The book offers an interesting perspective for young readers: that their own parents were once young and facing the uncertainties of life they must also come to grapple with, too; that their parents aren’t perfect. In that sense it is a humanising book and a fine addition to the Moomin stories which are, after all, if anything, about family.

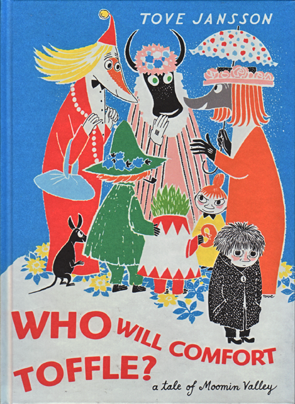

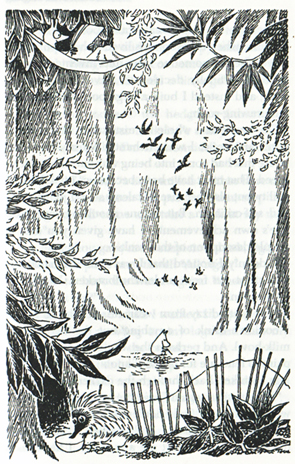

Jansson's illustration of the wild and unsettling party of the one hundred year autocrat. Like all her illustrations, it evokes a world of magic and wonder.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!