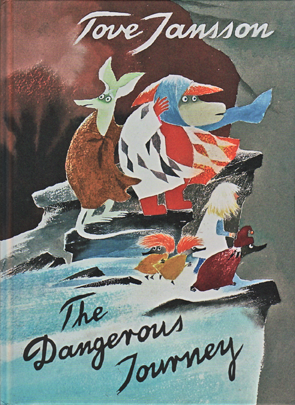

The Moomin Series #7

- Reviewed by: bikerbuddy

- Translator: Thomas Warburton

- Category:Children's Fiction

- Date Read:29 April 2022

- Pages:199

- Published:1962

Tales from Moominvalley is the sixth book in the Moomin Series. Unlike the previous books, this is a collection of nine short stories. The Sort of Books edition I own has an outline of the series at the back, and about this one it says, “Many Moomin fans love this book most of all.” I’ve read seven of the eight books from the series now, but it is not my favourite. Moominpappa at Sea retains that honour. But it would seem entirely possible that this book would be one of the most popular for many children, given the shorter form of the stories, which are varied in character and subject matter.

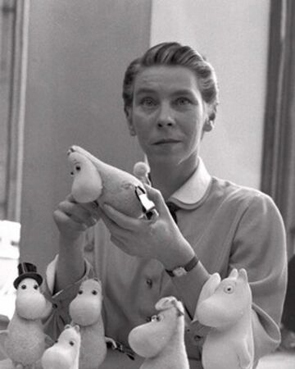

If you have stumbled upon this review and you are wondering what a Moomin is or what these books are about, all you have to know is that Tove Jansson was a Finnish writer who created her world as a place of mystery, of danger and wonder, as well as a place where the small dramas of childhood and family could exist within a mythic and magical setting. Moomins are small creatures – their size seems a little inconsistent across some of the books – who look something like upright and kindly hippopotamuses. The Moomin family are central to most of the books in the series, but in this book Jansson introduces some new and interesting characters independent of the Moomin family, as well as returning to us favourite characters like the reclusive Snufkin and the irascible Little My.

New characters like the Whomper are immediately recognisable to children. The Whomper is either themselves or other children they know as they negotiate the world or reality and fantasy. The fretful Fillyjonk seems familiar, too, because she is that overly anxious relative who lives alone. And the invisible child, Ninny, reflects the sense of withdrawal many children feel when they are treated with sarcasm and disrespect.

Favourite characters from the previous novels also have major roles in these stories. As always, the Hemulen is that fun-killer, well intentioned, but overburdened by his sense of the importance of rules and order. When he repairs a fun-park for the local children, he naturally insists that no-one make noise, not even the rides. The Hattifatteners remain mysterious, with their silent ability to work as a kind of hive, and draw upon the forces of nature – the electrical energy of storms – to feed. Snufkin is that cool, elusive loner, whose desire for solitude is sometimes eroded, despite his best efforts to remain aloof. And of course there is the Moomin family, too, with two of the most intriguing and interesting stories of the collection.

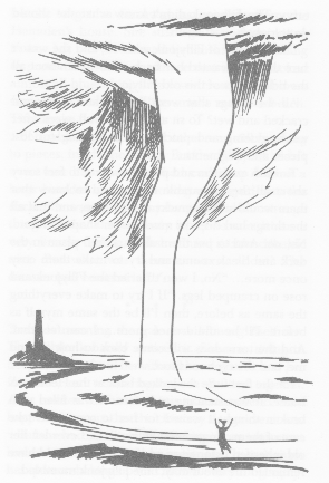

The story ‘The Secret of the Hattifatteners’ is the longest in the book. Moominpappa, whose key characteristic across the series is his restless desire for purpose, climbs into a boat with three Hattifatteners without consciously understanding why. This story feels like a prelude to Moominpappa at Sea. In that tale, Moominpappa takes his family to live on a deserted island to become a lighthouse keeper. Life has become too boring and predictable for Moominpappa, and he feels unneeded, now, by his family. Likewise, in ‘The Secret of the Hattifatteners’, it would seem that Moominpappa seeks a remedy for his ordinary life in which, “the weather was hot and boring.” Without thinking, he joins the Hattifatteners. Hattifatteners are silent creatures – tube-like without legs – who move in odd-numbered groups. Their presence is mysterious and unnerving, and they are reported to be able to read thoughts and are rumoured to live ‘wicked’ lives. Moominpappa seems drawn to the promise of something exotic. But when he witnesses their congregation and the power they draw from the thunderstorm, Moominpappa realises his desires can potentially lead him from his true nature: “What’s come over me? I’m no Hattifattener, I’m Moominpappa… What am I doing here?” It is a thought followed by a more formative insight: “[The Hattifatteners] were heavily charged but hopelessly locked up. They didn’t feel, they didn’t think – they could only seek.” The promise of something larger, perhaps more purposeful, Moominpappa realises, proves to be an illusion.

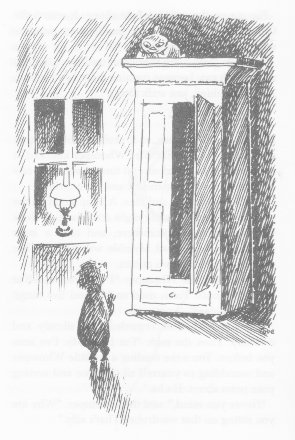

As usual with Jansson, her simple tales belie their philosophical weight. While Moominpappa’s story touches on aspects of identity, purpose and one’s place in the world, others in the collection cover a range of experiences and insights: of solitude and independence; of a sense of wonder for the world; of the determination for free-thinking; of curiosity; of restlessness and fear. The characters and their interactions with their world is of primary importance, and key to that experience is a sense that the world is wider and more dangerous than can be known. Snufkin, a little like Moominpappa, ranges beyond Moominvalley, although his determination lies with his fierce independence and desire to remain untrammelled by obligation and the burden of possession. “You can’t ever be really free if you admire somebody too much,” he advises the Creep (a small creature who does not deserve the usual pejorative associations of the word). He is uncomfortable talking about his life, even, because he fears that doing that can destroy the magic of solitude. And his refusal to be burdened by obligation or anything but the barest of possessions is the antithesis of the Fillyjonk who sits in her house full of possessions, ever fearful of the disaster that will come to take it all away. Typical for Jansson’s characters, it is only when disaster comes that she has an insight – she will give everything away – and she becomes truly free and happy. It is a sentiment also hinted at in the last story, ‘The Fir Tree’, which features the Moominfamily again. Moomins hibernate during winter, and when they are awakened by the Hemulen so that they might prepare for Christmas, they are somewhat bewildered because they have no idea what Christmas is. Nevertheless, through clues and a fearful concern that they need to placate this thing called ‘Christmas’ which is coming for them, they glean the rudiments of the season – the tree, ornaments, food and presents – and await their fate. But when the Woodies, who have never been able to afford a Christmas, explain that Christmas is what they have created, not a fearful force from outside, they immediately divest themselves of their burden so they might return to their happy world of hibernation. They give everything to the Woodies. Moomintroll, still somewhat confused by the whole thing, observes, “I believe the Hemulen and his Aunt and Gaffsie must have misunderstood the whole thing.” Ironically, the Moomins have kind of gotten it right.

All the stories in this collection have the same magic quality which imbues Jansson’s other Moomin books. And while this short form prevents the development of a more complex narrative, the stories are charming, as are the characters. The interrelationship of circumstance and theme from one story to another also provides a worthwhile and satisfying reading experience. In fact, these shorter stories may work more effectively for younger children than the novels, so they would be a great introduction to the world of the Moomins. Each is short enough to be read at bedtime, for instance, and would provide an excellent opportunity to extend that practice with children between the ages of five and ten. The stories are not only entertaining, but with an adult’s guidance, they could provide the catalyst for discussion and positive engagement. Like all Moomin books, Tales from Moominvalley comes highly recommended.

In Tove Jansson's Moomin books, the familiar everyday world can become mysterious, magical or even threatening.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!