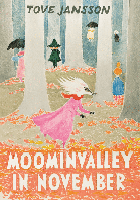

The Moomin Series #8

- Reviewed by: bikerbuddy

- Translator: Kinsley Hart

- Category:Children's Fiction

- Date Read:30 March 2020

- Pages:208

- Published:1965

It was during late primary school, around the period when our family had just moved to a new house, that I discovered Tove Jansson’s Moomin books. I fell in love with them instantly. To give an idea of how long ago that was, I can tell you that I kept in touch with a friend from my old school by writing letters. Yes, this involved putting a postage stamp on an envelope, putting it in a mail box and waiting for a reply. In one letter I told my friend about these new books I had discovered. Never much of a drawer, myself, I nevertheless had quite a good eye for detail and was able to reproduce images quite faithfully. So, I drew some of the main characters in the margins of my letter to illustrate what I was talking about. My family moved back to our old suburb about two years later and I returned to the same school. But my friend who received my letter about the Moomins never gave any signs that I had inspired him. In fact, he thought I was something of a twat for reading books, so there!

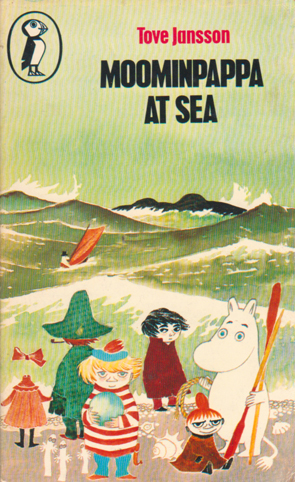

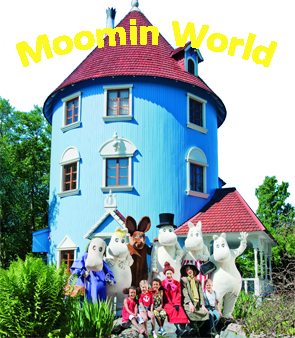

Tove Jansson first started publishing the Moomin books in 1945 with The Moomins in the Great Flood. The Moomins are described as a kind of troll, large snouted, cute and well-natured, as you might surmise from the illustration. Jansson was a Swedish speaking Finnish illustrator, and she illustrated all nine of her Moomin books along with several picture books. My first Moomin book wasn’t Moominpappa at Sea – that came later and was to be my favourite of the series – but Finn Family Moomintroll. I was first drawn in by the map of Moominvalley, Jansson’s illustrations and Moominmamma’s letter to the reader. Dear Child

, she began in her curling script. She explained what Moomins were (is it really possible you havent any Moomintrolls

) and apologised for her poor spelling (…you see moomins go to school only as long as it amuses them

). Looking back, I think it was that letter that inspired me to write my own, complete with illustrations. I remember idly copying the map later on and then becoming obsessed with drawing my own worlds. As the years wore on, I managed to keep my Moomin books in pretty good shape and they still sit on my book shelf. I re-read the same copy I read over forty years ago, which was satisfying. Of the stories themselves, what stuck in my memory most over those years was the melancholy, haunting tone of Moominpappa at Sea.

Fast forward to 2020, and one night I’m watching The Grand Tour with the family. Clarkson, Hammond and May are in Finland and on a screen there appear the heads of famous Finns. None of them are female. In fact, Clarkson says there were no famous female Finns, to his surprise, and I almost leap out of my seat like some ingenue watching theatre, thinking I might refute him, saying, What about Tove Jansson?

.

It’s what brought me back to this book. That, and I wondered whether I would find it as compelling now that I’m older.

When I was a child, I was taken in by the Moomins’ land, the strange creatures that inhabited it, their adventures and their good humour. There was magic in these books, and there was even mild terror. The Groke, a lonesome creature that freezes the ground upon which she walks, stayed with me long after many other details of the books were lost to memory.

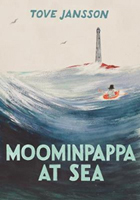

In Moominpappa at Sea, the Groke follows the Moominfamily across the sea from Moominvalley to a desolate island in the far north of the world. Upon the island’s southern headland sits a lighthouse that Moominpappa decides he will occupy. Unlike Moominvalley, where life has become easy and his family independent of him, life will be full of new challenges and Moominpappa will be purposeful once more. That’s where we’re going to live,

Moominmamma tells their son, Moomintroll, and lead a wonderful life full of troubles…

It’s an interesting insight in a children’s book. Moominpappa is aimless and fretful, because everything there was to be done had already been done or was being done by somebody else.

Moominmamma understands her husband’s problem, observing, Strange that people can be sad, and even angry because life is too easy.

In their new home she understands that it will be Moominpappa’s role to provide for and protect the family.

There is certainly much that could be discussed about the gender roles within the book that children – from the period the book was first published – would not have noticed. I think it’s unlikely young children today will question them, either, but adult readers will twig that something is happening here. Moominmamma feels like a traditional acquiescent wife, willing to defer to her husband over this life-changing decision. Her decision is that the move is proper

and she prepares for the journey with equanimity. Yet to focus entirely on this aspect of the novel would be to misrepresent its wider appeal. Partly, this is because the gender roles become somewhat fluid once the family reach Moominpappa’s island (his by right of desire, if nothing else). Tove Jansson’s Moomin family are traditionally structured, but on the island Moominpappa is shown to be mostly ineffectual. He can’t start the lighthouse, his attempt to build a breakwater is thwarted by a storm, his pretence at knowledge is quickly eroded and he dithers, spending his time on projects that have little practical purpose. Even when he captures fish, his efforts become so obsessive that Moominmamma risks hurting his feelings to hint that he should stop. Meanwhile, Moominmamma sets about turning the dingy lighthouse into a home. She cuts wood for the fire. She indulges herself in a wall mural of her garden from Moominvalley. At times, she is even capable of entering the painting while ever it soothes her aching homesickness, disappearing from her family, even before their eyes. In these ways, Moominmamma is both useful and independent.

Moominpappa, meanwhile, spends his time in scientific investigations of the island. He represents the patriarchal tradition of cataloguing and taming nature. He wishes to borrow Moominmamma’s paint to paint lines on the rocks to understand the behaviour of the tides. He trawls a bottomless

tidal pool at the end of the island, first in hope of finding treasure, and later in his desire to understand the sea. He has an old calendar upon which he attempts to keep time. He has an exercise book in which he writes his observations. But his conclusions are charming yet ill-informed, at least from a scientific point of view.

Moomintroll, meanwhile, sets about discovering the island on his own terms. He finds a tiny horseshoe which he reasons must belong to a seahorse; an entirely reasonable conclusion in Jansson’s fantasy. Moomintroll meets the seahorses and then subsequently waits night after night for each new encounter when they come to frolic in the waves and dance along the beach. He proposes moving into a glade hidden by a thicket, and his mother and father, progressive and trusting parents, allow him. Each night he also awaits the Groke who draws closer and closer to his hurricane lamp, crying a mournful dirge from her lonely, cold world. In his own way, Moomintroll grows in knowledge and experience on the island, and begins to understand the limitations of his father.

Moominpappa at Sea is not a typical children’s book; not the sort of thing one might expect to be published now, I think. At the heart of Moominpappa’s dissatisfaction is an existential crisis about life and meaning. His dissatisfaction arises from a need for purpose, but Moominpappa cannot find purpose in quotidian routine. He deliberately casts his family away from the life they have led and the valley Jansson’s readers may be familiar with. Instead, his new theatre is the island and the sea, neither of which he fully understands, both of which become surrogates for a search for meaning and an understanding of life. As he trawls the depth of the rockpool he thinks that if he could only get everything up he would understand the sea, everything would fall into place. He would fit in, too.

He says of the sea, as he might of life itself, I want to know if the sea is really obstinate, or whether it obeys.

Later, he laments, There’s just no rhyme or reason to it. And if there is, it’s more than I can understand.

It’s these themes that made the book so enthralling and haunting for me as a child reader. Jansson’s work suggests a larger world, not necessarily made for children. There is danger. There is mystery. There is beauty. There is solitude, quiet and time for contemplation and growth. And unlike many children’s books, Jansson’s protagonist is a father, even though Moomintroll is there for the younger audience. His concerns are adult concerns and their presence in Jansson’s oeuvre suggests a more troubling and complex world than many of her young readers might previously have experienced. Reading this book left me open to wonder. It is a book that is potentially formative, not just entertaining.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter