The Moomin Series #6

- Reviewed by: bikerbuddy

- Translator: Thomas Warburton

- Category:Children's Fiction

- Date Read:28 July 2021

- Pages:168

- Published:1957

Tove Jansson’s fifth book in the Moomin series is the first set in the world of Finland’s winter. Moomins, like many creatures in cold climates, hibernate during the winter months. But this time, Moomintroll wakes in the middle of winter and is unable to fall asleep again. Try as he might he cannot wake his family to keep him company and so, for the first time, he finds himself entirely alone and in a strange environment. Moomintroll has only ever before experienced snow as a remnant during spring. Now, during winter, he sees that snow piles against the Moomin House to its roof, and it is impossible to get outside by the doors or windows. Instead, he is forced to leave the house through the chimney sweep’s hatch in the attic. Outside, he finds a dormant landscape, bewitched and dreamlike, cold beyond his imagining, with a frozen river and creatures he has never met before: the creatures of winter.

Moominland Midwinter ably evokes the sense of wonder and magic that Jansson’s previous novels in this series achieve, but it is a different tone and mood to her previous book, Moominsummer Madness. As the title suggests, that book is chaotic and carnivalesque, as the Moomins adjust to life in a floating theatre, while at the same time attempting to entertain the creatures who live in the flooded Moominvalley. Nevertheless, Moominland Midwinter has common themes with that book, as with other books in the series: the sense of displacement; of a wider and more mysterious world than our own limited experiences allow, as well as the possibility that we might grow with new experiences. But in Moominland Midwinter, Jansson reorientates Moomintroll’s perspective, making his familiar world unfamiliar, and forcing him to reassess his assumptions about new people – he does not like the winter Hemulin, for instance, but he develops sympathy for his good nature – and his understanding of his own place in the world.

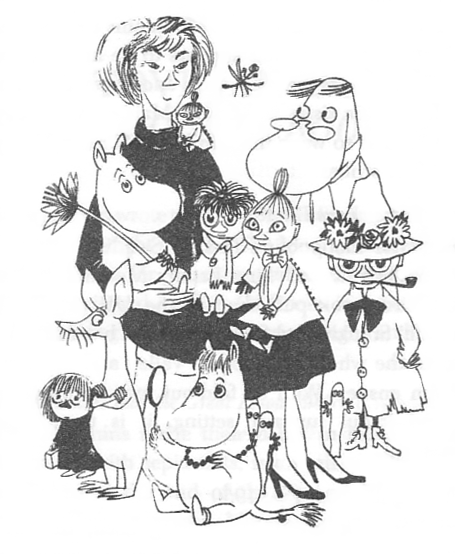

Jansson rarely sugar coats her world for her readers. It is both beautiful and dangerous; an opportunity for fun as well as a challenge. And her most philosophical characters never see the world in absolutes. In Midsummer Madness, it is Snufkin, a kind of sixties beatnik who rails against authority, who tears down signs that forbid any kind of fun. Snufkin is not tied to possessions and heads south each winter and returns each spring, giving him a wider perspective of the world. In Moominland Midwinter, Snufkin is absent; gone south. All that he leaves is a note for the Moomin family wishing them well. Yet Snufkin’s philosophical bent is necessary to Jansson’s narrative, and she provides an able substitute for Snufkin with Too-Ticky in this novel. There is no veracity in my thinking, I know – at least none I know of – but I came to think of Too-Ticky as a version of Jansson, herself, inside the narrative. I knew that if I was a child reading this book – a child who had some exposure to Jansson’s life, at least – I would have thought this. Too-Ticky’s distinctive look, with her red-striped top (Too-Ticky appears on the cover of older versions of Moominpappa at Sea even though she does not feature in that book) is tantalisingly similar to several dresses and tops Jansson wears as a child in her memoir, Sculptor’s Daughter. Putting that aside, it is Too-Ticky’s pronouncements to Moomintroll that make her most like a winter version of Snufkin. When she first meets Moomintroll she reflects upon the Aurora Borealis, a motif in this novel: “You can’t tell if it really does exist or if it just looks like existing. All things are so very uncertain, and that’s exactly what makes me feel reassured.” Too-Ticky is awake to the paradoxes of snow, and hence of life: “You believe it’s cold, but if you build yourself a snowhouse it’s warm. You think it’s white, but at times it looks pink, and another time it’s blue. It can be softer than anything, and then again harder than stone. Nothing is certain.” Too-Ticky’s insights are personified by Moomintroll’s dilemma. He has entered a world he doesn’t understand, where he can hardly know his own reality: “I don’t belong here anymore,” he thinks. “I don’t know what’s waking and what’s a dream.”

Faced with this new, uncertain world, Moomintroll has no choice but to find his own place in it. And like Moomintroll, the reader is opened to new possibilities for friendship and family. When Moomintroll comes across the cupboard troll, an irascible character that wants to be left alone, Too-Ticky tells Moomintroll that the troll is an earlier version of Moomins, “…how you looked a thousand years ago”. He must also learn the limits to his new world. Moomintroll represents the childhood struggle to fit in and understand the world. When he first walks into a blizzard he becomes angry. He shouts at the gale, strikes the snow and whimpers with fright. But as he becomes accustomed to this environment, he feels an affinity with his new reality: “I’m nothing but air and wind, I’m part of the blizzard,” he thinks. “It’s almost like last summer. You first fight the waves, then you turn around and ride the surf…”

But there are always limitations. Sorry-Soo, another new character (a dog in a hat) hears the wolves howl across the winter snow, and like Moomintroll drawn to his ancestor, is drawn by atavistic longings to know his wolf pack. But Sorry-Soo, encounters ferocious wolves, not family.

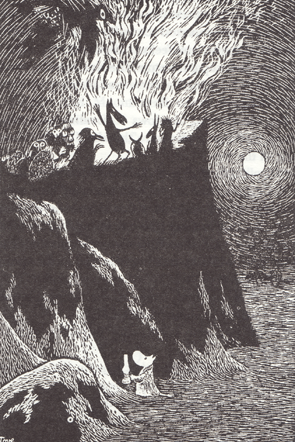

There is an ever-present sense of beauty and danger, of antipathy and sympathy, just as Too-Ticky’s philosophy suggests. The Lady of Cold, a woman of mystical power who can freeze creatures with a look, is immensely beautiful. The Groke, a creature who appears in several Moomin books, is a figure of terror for the Moomins. Wherever she moves, the ground freezes. Whatever fire she sits upon is extinguished. But we also sense the lamentable misery of the Groke, forever alone, seeking warmth and companionship.

Moomintroll becomes the first Moomin to have been awake during winter, although with the novel’s dreamlike quality, it is hard to know for certain. What is certain is that Moomintroll has had an insight into his world, one way or another. His perspective, like Snufkin’s, is less parochial. If I can pretend, against any critically accepted practice that Too-Ticky speaks for Jansson, then Moomintroll, I can allow, is a surrogate for the child who reads this book and senses a wider universe beyond their own experience. Moomintroll’s self-assurance and resilience is stronger. It is like Too-Ticky says: “One has to discover everything for oneself […] and get over it all alone.” As always, I recommend these books because they are magical and insightful.

In Tove Jansson's Moomin books, the familiar everyday world can become mysterious, magical or even threatening.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!