The Moomin Series #9

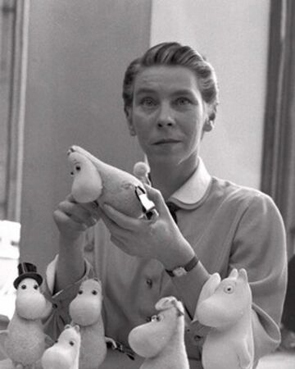

- Reviewed by: bikerbuddy

- Translator: Kingsley Hart

- Category:Children's Fiction

- Date Read:28 May 2022

- Pages:206

- Published:1971

Moominvalley in November is the last in the series of Tove Jansson’s Moomin novels. Typically of the series, it is something of a peculiar novel for children when you think about it. The story is populated by social misfits – people who would normally find comfort in their own solitude – while the nominal main characters of the series, the Moomins, are absent. It sets up an interesting dynamic for the reader. Children who long to return to Moomintroll’s adventures, or the comforting presence of Moominmamma, or the restless wanderings of Moominpappa, are denied those familiar tropes. Instead, the Moomins are still living on an island Moominpappa has taken them to in the previous book, Moominpappa at Sea, in which he becomes a lighthouse keeper. That book represents the height of Tove Jansson’s creative powers: its haunting tone, its philosophical underpinnings and the eerie world which Jansson evokes. Moominvalley in November, then, might be read as a story in parallel, and in its own way it approaches the maturity and interest of Moominpappa at Sea.

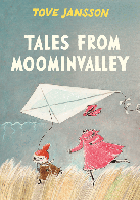

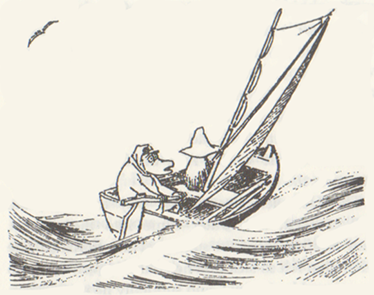

In Moominvalley in November the Moomin house lies empty as winter approaches. But other creatures in Jansson’s universe whose lives have been touched by the Moomin family feel compelled to visit them, unaware of their absence. We have already met some of them. Snufkin, who represents a kind of counter-culture wanderer, eschews company and is fiercely independent. Yet he feels the need to return to Moominvalley when he finds no inspiration for a tune he is trying to compose. The Fillyjonk, whom we have met in Tales from Moominvalley, is an obsessive cleaner who lives alone. But a near accident forces her to pause and consider her life, which leads to her decision to visit the Moomins. The Hemulin, who likes nothing better than to organise other people’s lives, is dissatisfied with his own life and frightens himself with his desire to go sailing in his boat, which he repairs every year but never uses. His fear of sailing pushes him to think of happier thoughts, and he remembers vaguely having liked the Moomin family whom he met some time ago. Mymble also ends up at the Moomin house, wishing to visit her sister, Little My. But Little My is also on the island with the Moomins.

Jansson also introduces new characters who become a part of the Moomin house menagerie. Toft, who lives in the underside of the Hemulin’s unused boat, desires to be a part of a ‘Happy Family’. For Toft, as for the others, the Moomins represent that standard. He has wandered in the Moomin garden, has looked at Moominpappa’s woodshed and at the crystal ball that adorns the garden. But most of all, he has longed for Moominmamma as a mother figure. He has only ever seen her from outside the house.

Finally, there is Grandpa-Grumble, an old man of over a hundred who, much like Jonas Jonasson’s old man who escapes his nursing home, decides to seek adventure. He is tired of being shouted at and told he is silly. He may not remember his own name – ‘Grandpa-Grumble’ is merely a name he has chosen – but he has a firm determination to see the world, and the world he sees is largely formed by his imagination.

Each of Jansson’s characters lacks something, whether it be confidence, inspiration, love or purpose. Each wants something from the Moomin family, but instead, finds only the empty family home and the company of their new companions.

As always, Jansson’s writing is deceptively simple. If Jansson’s child reader longs for the Moomins in their absence, so too is the longing of each character manifested in various ways. Even the independent and irascible Snufkin feels a sense of loss when he cannot find a note from Moomintroll in any of their hiding places. For other characters, the Moomin absence represents a deficiency in their own lives or their sense of self. The Fillyjonk has a strong need to take over the working of Moominmamma’s kitchen and play the part of Moominmamma. Grandpa-Grumble is obsessed with the idea of the Moomin ancestor, purported to be over three hundred years old, and therefore older than himself. Mymble, without ever expressing a sense of loss, nevertheless brushes Toft’s hair as she would normally do for her sister. The Hemulin is compelled to visit Moominpappa’s bedroom and meditate upon Moominpappa’s possessions. His desire to emulate Moominpappa’s adventurous exploits will prove beyond his level of comfort. And Toft, the most poignant character, longs to be mothered. His thoughts often return to Moominmamma, until her level of perfection in his imagination is beyond the bounds of reality.

And it is imagination that is of primary importance in this story. Imagination becomes the basis of aspiration. These characters, on the whole, are redefined by their aspirational desires. It is not only Toft’s imaginative transformation of Moominmamma which must be set against reality. Toft, upon reading one of Moominpappa’s books, is somewhat perplexed by the scientific subject – he reads about a particular kind of Nummulite which has attained an electrical affinity with storms, which recalls the Hattifatteners of previous books – and from his reading his imagination fills the void his understanding cannot span. He imagines, instead, a Creature he fears stalks through Moominvalley, particularly when a storm approaches. His Creature finds its equivalent in a swarm of insects the Fillyjonk imagines she has set loose on the valley when she opens a cupboard.

Meanwhile, Grandpa-Grumble insists that the Moomin River is not a river, but a brook: the connotations of that word suggest a quiet retreat where fish may be caught handily, rather than the reality of the brown river where fish are hard to catch at this time of year. Grandpa Grumble is the most striking example of how reality is transformed in the period these six characters inhabit the Moomin home, and imagination becomes possibility. His desire to make contact with the family ancestor leads him to accept his own reflection in a wardrobe mirror as an avatar for that missing character.

The Hemulin’s personal aspirations are based on a false sense of his own competence. So, while ever his intentions to sail are forestalled he can imagine that sailing is a part of his identity. And though he may wish to build a tree house for Moominpappa to enjoy upon his return, his vision is whittled, first by planks of wood that are sawn to the wrong length (for which he blames Toft), to the walls falling apart, and eventually the floor, itself, collapsing. There is something charming in the Hemulin’s reassessment of his goals with each setback, but we understand his limitations better than he does. Each of the characters inhabit the Moomin house as long as they play the part of Moomin surrogates and maintain the pretence of their own aspirations. They are innocents when it comes to their desires, which is both inspirational and moving: while each character’s sense of a new life withers into their old, they return to their lives with greater acceptance and tranquillity.

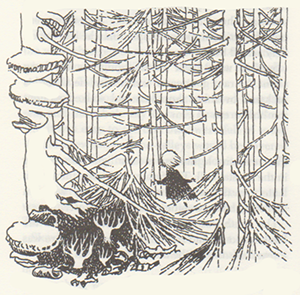

What I found striking about this book was Jansson’s willingness to dismantle her own imaginative world. The Moomin series is one of the most original and moving children’s series that I know. Yet she was willing to finish it with the main characters off-stage, their parts played by understudies. Further to that, is the dismantling of her imaginative world at the end of the story. Moominvalley is a magical place for a child. I know, because I read a number of the Moomin books when I was young. The map in Finn Family Moomintroll with its fantastical detail, encouraged exploration and speculation. The illustrations of the Moomin world throughout the series, drawn by Jansson herself, capture some of the mysterious and exciting places that Jansson is describing. But as this novel closes, the characters depart and winter is closing in. Toft enters the forest, close to the Moomin home, and instead of enchantment Toft faces a reality that is often alluded to throughout the series:

He jumped up and started running, he ran past the kitchen-garden, the rubbish-heap, straight into the forest and all of a sudden it was dark, he was in the waste ground, the ugly abandoned forest that Mymble had talked about. Inside there was perpetual dusk. The trees stood uneasily close to one another, there wasn’t enough room for their branches, and they were all quite thin […] No one had tried to make a path here and no one had ever rested under the trees. They had just walked around with sinister thoughts, this was the forest of anger.

Toft’s insight allows him to let go of his idealisations of the family, even of Moominmamma: “This is where Moominmamma had walked when she was tired and cross and disappointed and wanted to be on her own, wandering aimlessly in the endless forest lost in her dejection…” Even so, Toft awaits for the family’s return. This is what I love about Jansson. There is magic, but it is not cloying. Her world is full of compassion, but it is also touched by danger and mystery. Jansson understands what children want from a story, but she also understands what they need, too. The Moomin books are special. They deserve to be read.

“The forest began to thin out and huge grey mountains lay in front of him.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!