The Moomin Series #3

- Reviewed by: bikerbuddy

- Translator: Elizabeth Portch

- Category:Children's Fiction

- Date Read:23 October 2020

- Pages:173

- Published:1950

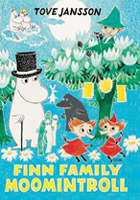

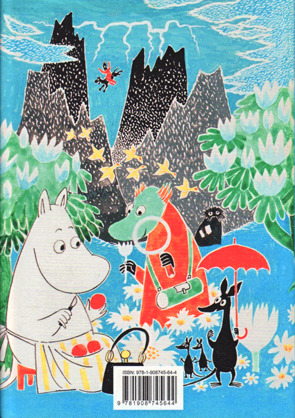

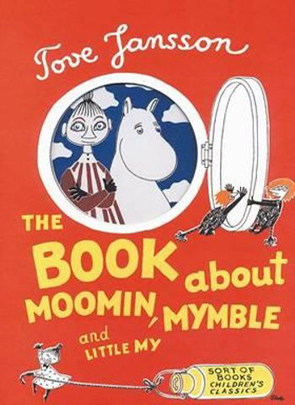

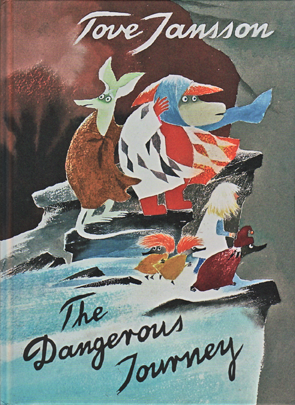

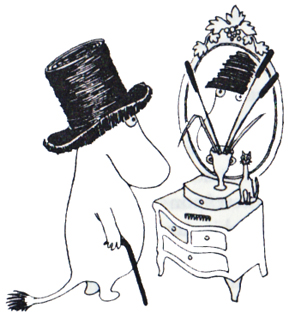

Finn Family Moomintroll is the fourth book in the Moomin series I am reviewing for this website (It’s the third in Jansson’s Moomin novels, but I’m a bit out of order). It is also the first I read as a child. I still have my original paperback and even now I can glean a little of what first drew me to this book. Naturally, there is the bright colours, joyful and otherworldly. The cover is illustrated by Jansson herself (as are all the illustrations in her books). The cover shows a cast of characters all good-naturedly inhabiting their world, along with a strong sense of mystery. On the back cover, mountains loom in the near distance, with a filigree of lightning shattering the sky and a man riding what appears to be a large dog. It is, in fact, the Hobgoblin on his panther. Apart from that, all the creatures are fantastical and friendly. There stands Moominpappa with his cane, wearing the hobgoblin’s hat, unperturbed by the Hattifatteners or the Groke, both sources of fear in the novel. There is so much going on in this cover for a child to wonder about.

However, I never made much of the title as a child. The original Finnish title, Trollkarlens Hatt, roughly translates to Hobgoblin’s Hat, Google tells me. The English title, on the other hand, seems to be a reference to Johann David Wyss’s nineteenth century novel, The Swiss Family Robinson. If that was the intention, it is a little misleading. Wyss’s story has his Swiss family shipwrecked on the way to Australia. In Finn Family Moomintroll the family sets out in a boat in an extended sequence in the middle of the novel and lands on the island of the Hattifatteners, strange tube-like creatures that neither hear nor speak, but worship a barometer and seem to draw electricity from storms. The island sequence anticipates some of the scenes from Jansson’s later book, Moominpappa at Sea, in which the family leave Moominvalley to live on a deserted island with a lighthouse. In Finn Family Moomintroll, the characters survive a storm and the creepy presence of the Hattifatteners, and when the storm passes, they find treasures washed upon the beach.

But the sequence on the Hattifatteners’ island represents only a part of the wider themes of Jansson’s novel. This is a novel about growing and discovery, along with the notion of change and the rhythms of nature. The novel begins with the Moomins and other creatures of Moominvalley settling in to hibernate for the long Finnish winter. When they awake it is Spring again, and we follow them on their adventures. The novel is fairly episodic, following the various adventures of the characters through the Summer and back into early autumn.

What unites the sequences is the discovery of the Hobgoblin’s hat on the first morning of their exploration in Spring, high on top of a hill, which is why a direct translation of the original title might have been better. The Hobgoblin’s hat is magical. It transforms any object or creature that happens to be put into it, at least temporarily. When Moomintroll plays hide and seek with his friends, he hides in the hat, only to be transformed beyond recognition. It provides one of the most touching scenes in this or any children’s book, the proof of a mother’s love. When he cannot convince his friends he is Moomintroll, he turns to his mother: Look carefully at me, mother.

Moominmamma looks carefully and agrees he is Moomintroll. He immediately begins to change back. You see

his mother says, I shall always know you whatever happens.

The hat provides opportunity for fun, too. When the family begins to use it for waste, some eggs thrown into the hat transform into clouds which can be ridden like floating go-carts. Throughout the story, Moomintroll, his family and friends either are delighted by the hat, or afraid of its potential. They are both carefree and careful with it. They hide it in a cave by the beach, but of course the muskrat, an-all-too-serious creature concerned too much with his own dignity, decides he must be alone, and retreats to the cave. When he puts his false teeth in the hat, we can only imagine what is the outcome: ask your mamma

Jansson advises in a footnote.

Common to the Moomin stories is a dual sense of security and homeliness, tempered by a sense of threat from without. Whether it be the harsh Finnish winter, the Groke who freezes the ground upon which she moves, the Hattifatteners or the Hobgoblin himself, we sense that the Moomins live in a small Utopia bordered by a wider world. When the Snork Maiden finds a ship’s figurehead floating on the tide of the Hattifattener’s Island, she falls in love with it and is proud that it offers her the opportunity to do something independent by bringing it back to her friends. But as readers, we are also aware of the wider world from which it came and the disaster that probably brought it into the story. And there are malevolent presences in the story, too. Searching for his King’s Ruby in the craters of the moon, the Hobgoblin is nevertheless is spotted as in a vision by the Hemulin during the storm on the Hattifattener’s Island, a seeming harbinger of danger riding his panther upon the cloud bank. Snufkin, the worldliest of the creatures, because he neither treasures possessions nor is tied to a place, tells the Hemulin who is frightened by the Hattifatteners, Life is not peaceful

. It is the hard reality at the centre of the stories that prevent them being facile or overly sweet. When Moomintroll and his friends are offered wishes by the Hobgoblin, they represent a range of thoughtful and foolish choices, all with the potential to create unhappiness as not. The characters make mistakes and they must learn from them. But even so, at the end of everything, this is a magical world in which grand concerns can turn upon the finding of Moominmamma’s handbag.

Finally, Finn Family Moomintroll comes with its own map, drawn by the author, showing Moominvalley, the Hattifattener’s Island, as well as plans of the Moomin house. The hardback Sort of Books edition, which I have used for this review, is beautifully presented, but unfortunately does not include a letter from Moominmamma to the reader (Dear Child

) written by hand with a cursive style with curling ends, complete with bad spelling (because Moomins go to school only as long as it amuses them

: how wonderful!) The writing is actually a little difficult to read for a child, but it looks wonderful, even Moominmamma’s attempt to explain what a Moomin is and her somewhat simplistic drawing, which is charming.

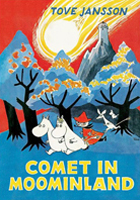

Finn Family Moomintroll is a more loosely structured story than its predecessor, Comet in Moominland, but it has all the same magic and quality. These books are highly recommended.

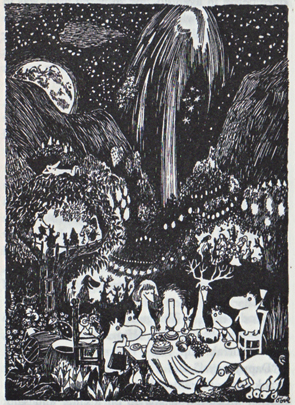

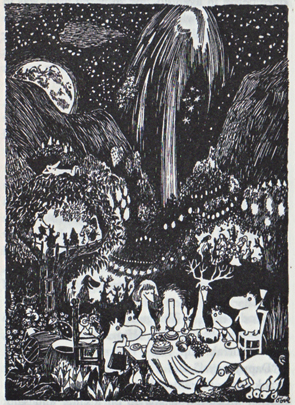

Jansson's illustrations suggest a Utopian world bordered by a wider world of mystery, even danger.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!