Scenes of Clerical Life is the first book by George Eliot I have read. I had an idea that I would read Middlemarch, her most popular work, and then decided, instead, that it would be interesting to read that novel in the context of Eliot’s other work. For this reason, I decided to read her books in the order of their publication. As I read the books I may return to this review to amend or add to it.

Marian / Mary Anne / Mary Ann Evans

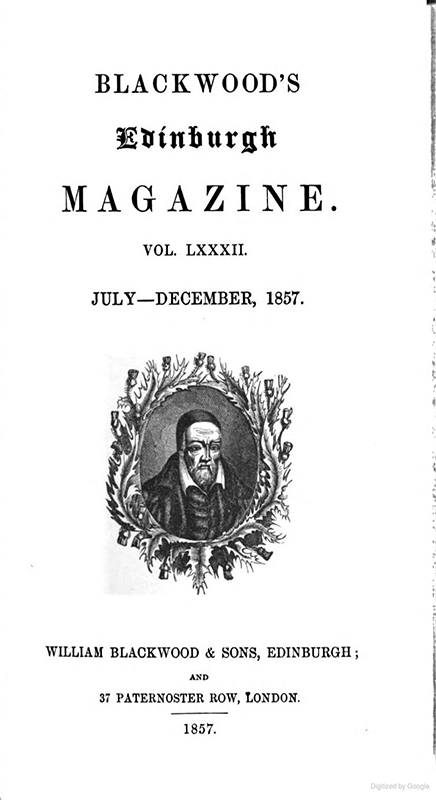

Scenes of Clerical Life was Marian Evans first published fiction. Writing under the pseudonym ‘George Eliot’, she would become one of England’s best novelists and receive praise from literary giants like Charles Dickens and William Thackeray. For the purposes of this and other reviews that follow, I will refer to Marian Evans by her literary name, hereafter.

The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton

When discussing the first story of Scenes of Clerical Life, ‘The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton’, I will not refrain from revealing aspects of the plot, although I will not discuss details of the most salient moments. For the last two stories, I will avoid spoilers when discussing their plots.

In ‘The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton’, Eliot’s narrator asks her audience to picture Shepperton Church and the improvements that have been made over the last 25 years since Amos Barton was curate: the slated roof that replaced the old tiled roof, the tall windows, the oak-grained doors, and so on. During the period of Reverend Amos Barton’s tenure, the church was smaller. It is a part of the story that Barton is undertaking a renovation of the church. The improvements, the narrator quips, “are as smooth and innutrient as the summit of the Rev. Amos Barton’s head.” The word ‘innutrient’ is a peculiar choice. It refers to the walls upon which “no lichen will ever again effect a settlement.” Barton is bald, we smile to ourselves. But the real point is that the ‘improvements’ lack character. Half a page later, when it becomes apparent that Barton’s church is a metaphor for the changing landscape of English culture. There has been “the New Police” (the Metropolitan Police Act of 1829 introduced by George Peel replaced watchmen and parish constables with a professional police force), “the Tithe Communication Act” (of 1836, which abolished payments of tithes in kind) and “the penny-post” (the Uniform Penny Post system employing postage stamps was introduced in 1840). Eliot’s narrator laments,

… that dear, old, brown, crumbling, picturesque inefficiency is everywhere giving place to spick-and-span new-painted, new-varnished efficiency, which will yield endless diagrams, plans, elevations, and sections, but alas! No picture.

The three stories that comprise Scenes of Clerical Life are set across a fifty year period. ‘The Sad Fortunes of Amos Barton’ is set “five and twenty years ago”. Internal evidence suggests it is set sometime around 1837-8: “The new Poor-law had not yet come into operation,” we are told. The Poor-law, passed in 1834, took several years to implement in some counties. We are also told that Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers has recently been completed, placing the date close to November 1837. However, that would make the ‘current’ date around 1862 (the story was published 1857), suggesting some internal inconsistency.

The second story, ‘Mr Gilfil’s Love-Story’, predates the first by five years (“When old Mr Gilfil died, thirty years ago”) to begin with, but extends as far back as 1788 in chapter 2, to tell Caterina’s origin story.

The final story, ‘Janet’s Repentance’, is set “More than a quarter of a century” before the time of the narrator (who appears occasionally in this final story and is male). The narrator stresses the social advances made since the time of his narrative: the church has been enlarged; a grammar-school has been built; there is a book club; there is gas lighting on the streets. None of these innovations are apparent in the first story, either.

In ‘Amos Barton’, Eliot immediately creates a dichotomy between past/present that appeals to the atavistic emotions that nostalgia evokes. And a few pages later she further embellishes this dichotomy by suggesting there is even a qualitative difference between country and city life – between country and city people, who represent conservative and progressive classes, respectively – with a contemptuous aside at her reader: “Reader! did you ever taste such a cup of tea as Miss Gibbs is this moment handing to Mr Pilgrim?” she asks. Eliot's reader, she assumes, has been bred upon something inferior: “No – most likely you are a miserable town-bred reader, who think of cream as a thinnish white fluid, delivered in infinitesimal pennyworths.” Eliot’s relationship with her reader is most peculiar in this first story. At the beginning of chapter 5 – the first chapter in the second part of the story published by Blackwoods – she imagines her audience almost as a presence: “I think I hear a lady reader exclaim – Mrs Farthingdale, for example …”, and continues by provoking her readers, “if you please, decline to pursue my story farther.” Eliot is challenging her audience, not merely to stop reading – we assume that is not what she really intends – but to accept her fiction on her terms. Rather than seeking “remarkable novels, full of striking situations, thrilling incidents, and eloquent writing”, she suggests that her readers find “pathos” in the insignificance of her characters: “in our comparison of their dim and narrow existence with the glorious possibilities of that human nature which they share.”

In short, Eliot attempts to excise the modern sensibilities and assumptions of her audience – its sophisticated cynicisms and narrow interests she seems to assume – to embrace a narrative about an England now bygone or going:

I wish to stir your sympathy with commonplace troubles – to win your tears for real sorrow: sorrow such as may live next door to you – such as walks neither in rags nor in velvet, but in very ordinary decent apparel.

These tensions play out in the story about Rev. Amos Barton, his wife Milly Barton, and Countess Czerlaski, who comes to live with them after her brother marries a servant. The Bartons must try to live on 80 pounds annual stipend for Barton’s work as curate in Shepperton. They have six children with another on the way, and their financial resources are stretched to their limits. And Barton faces opposition in the town, between those who adhere to traditional Anglican practises, and those who suspect Barton is a Dissenter, possibly a Methodist: he leads in the singing of unapproved hymns and he attempts to preach without reference to the Bible, extempore, although he has no talent for it. Many of his parishioners are poor, but he seems incapable of drawing upon his own experience to appeal to them. Instead, his preaching tends to be a little too academic, and he can be tone deaf to their needs. Added to this, Barton is squeezing his parishioners – even those who disapprove of him – to contribute to the building fund for the church renovation. When Countess Caroline Czerlaski arrives in town with her brother, Mr Bridmain, the town further turns against Barton. The Countess’s husband has died three years before and she has come to Shepperton where she hopes that competition for another husband will not be as fierce. After her separation from her brother, her presence in the Barton home is the fuel of salacious gossip, further damaging Barton in the eyes of the town. Added to this, the Countess’s presence in the Barton home during Milly’s illness and pregnancy puts further financial strain upon the family, without the mitigation of financial help, which the Countess is unable to give, or practical help. The Bartons suffer reputational and economic setbacks as a result.

This first story achieves the emotional impact that Eliot signals she wishes to achieve. The Bartons’s difficulties are complex and multifaceted, exacerbated by his parishioners who face the pressures of social changes to come. However, the voice of Eliot’s narrator is not quite as intrusive in the second half of the story, and she does not continue as strongly with its themes of social change. Instead, there is more concern over the matter of the Countess and her impact on the family, particularly on Milly, who is sick. I think this signals that there is no simple correlation to be assumed between the “picturesque” and “inefficient” past, and the religious values that are the subject of conflict in the story. Eliot’s relationship with faith was already complex: she claimed to be an atheist, so it is not possible to suggest she therefore defends Anglicanism against newer dissenting church creeds. In fact, if anything, the opposite may be argued. Barton is a suspected Methodist for whom Eliot garners a great deal of sympathy, especially with the poignant death of Milly and the loss of his position at the end of the story, replaced by Mr Carpe whose sole intention seems to be to pave the way for his own brother-in-law. And we will later read about Edgar Tryan in Eliot’s final story, whose Evangelicalism is to be admired rather than reviled. Rather than advocating a religious and cultural position, we find Eliot has challenged the reader to lay down their own prejudices to begin with in this first story, and by the end, the tragedy Barton faces has caused the people of Shepperton to abandon theirs.

The Religious Sphere

Eliot's chosen title suggests religion is the primary concern in these stories, and it does form their realistic backdrop. But by the end of ‘Amos Barton’ it seems clear that Eliot is most interested in the impact of religious and social changes on people's lives. The three stories work effectively together to progress these themes. The three narratives of Scenes of Clerical Life are often referred to as short stories, although I think by modern standards we might call them novellas. The longest, ‘Janet’s Repentance’, is 153 pages long in the Penguin edition, the shortest, ‘Amos Barton’, 69 pages. All three stories feature a church curate, but despite Eliot’s title, the book ostensibly focuses on the lives of four women: Countess Czerlaski and Milly Barton in ‘Amos Barton’; Caterina Sarti in ‘Mr Gilfil’s Love-Story’; and Janet Dempster in ‘Janet’s Repentance’. The stories feature some religious conflict, mainly around the issue of dissenting creeds like Methodism and Evangelism, but the “poetry and the pathos, the tragedy and the comedy” rests primarily with the experiences and fates of each of the women.

The tension between the public religious sphere – ostensibly patriarchal – and the private, represented by the fortunes of women, drives some of the conflict within the stories, which are at their most interesting when they focus upon the impact on the lives of Eliot’s female protagonists. Particularly in the third story, but also apparent in the first, the religious conflicts may be somewhat alienating for some modern readers. If, like me, you have no religious background, you may find yourself conducting searches on Google to pin down the history of some Christian sects, and the theological differences that brought groups of people with essentially the same beliefs, into conflict. This was even a problem in Eliot’s period. Her publisher, Blackwood, thought the opening chapters of ‘Janet’s Repentance’ too overburdened with description, along with the introduction of so many characters who form the factions within the town. Added to that are arguments over the origin of Presbyterianism at the beginning of the story, with references to Baptists, Methodists and Independents, not to mention the Tryanites and anti-Tryanites, whom the reader learns are factions either supporting or opposing a new Evangelical curate, Edgar Tryan, and the practices he has attempted to introduce to Milby. In ‘Amos Barton’, the conflict is not as fierce. There are disagreements about the choir and the Barton’s preaching extempore, not to mention the fact that he simply is not good at appealing to the ordinary folk of the town. But in ‘Mr Gilfil’s Love-Story’ the source of conflict does not reside with Gilfil, the curate, but Anthony Wybrow, a young cad who has wooed and won the heart of Caterina, only to cast her aside when the opportunity for a more socially acceptable (and profitable) marriage with Miss Assher presents itself.

Mr Gilfil’s Love-Story

What is unusual about ‘Mr Gilfil’s Love-Story’ is that it is hardly a love story at all. Eliot once again forces the action into the past, this time five years before Barton’s story. At the start, Gilfil has already died and is being mourned by his parishioners. His sermons were simple, often repeated and liked, yet he also appealed to the more well-to-do of his flock. And for the reader, Eliot’s narrator is once again intrusive, this time to speculate upon the nature of Gilfil’s romance:

But in the first place, dear ladies, allow me to plead that gin-and-water, like obesity, or baldness, or the gout, does not exclude a vast amount of antecedent romance, any more than the neatly executed ‘fronts’ [false curls] which you may some day wear, will exclude your present possession of less expensive braids. Alas, alas! We poor mortals are often little better than wood-ashes – there is small sign of the sap, and the leafy freshness, and the bursting buds that were once there; but wherever we see wood-ashes, we know that all that early fullness of life must have been.

It is a sentiment that echoes themes of ‘Amos Barton’. In that first story, Eliot argues for the pathos of ordinary lives as a proper subject for her fiction, in a line that extends right back to Wordsworth’s defence of ordinary themes in his Preface to the Lyrical Ballads. Now, Eliot enlarges her scope to include the romantic lives of ordinary people, even old people past our ordinary speculation about romantic pasts. Like the burned ashes of a tree which are evidence of a tree once bursting with life, the withered trunks of the old, perhaps now pruned and misshapen, are evidence of the lives which shaped them:

But it is with men as with trees: if you lop off their finest branches, into which they were pouring their young life-juice, the wounds will be healed over with some rough boss, some odd excrescence; and what might have been a grand tree expanding into liberal shade, is but a whimsical misshapen trunk.

Despite Eliot's title for this story, Gilfil is not our primary interest. Apart from his grief at the death of his wife, Caterina, only six months after their marriage – the fact is revealed in the opening chapter – Gilfil is not a complex character demanding our attention. He loves Caterina, which is in contrast to Wybrow’s ill-usage of her. It is Caterina’s “marble tablet, with a Latin inscription in memory of her”, and represented by the vague memories of the oldest town residents, which is the ‘wood-ash’ we are to sift. The story of Caterina is fairly straight forward. Delving into the past as far back as 1788, Eliot’s narrator tells us of Caterina’s childhood in Italy and how Sir Christopher Cheveral and his wife took her into their care after the death of her father. Raised in a privileged English setting, she is loved and cared for. Nevertheless, she is not treated as a full member of the family, but as a ‘protegée’, intended as a help in the family home and business. As an Italian, there is the merest hint that her race will be a barrier to her happiness, not to mention the imposition of Protestantism by the Cheverals to replace her Catholic identity: “to graft as much English fruit as possible onto the Italian stem.” Caterina’s ambiguous position in the family is also reflected in Sir Christopher’s ambitions towards posterity. Without children of his own, he begins a building project – much like Amos Barton – to renovate Cheverell Manor in the Gothic style. Mrs Bellamy, the housekeeper, laments they will be poisoned with lime and plaster, and points out that the presence of workmen in the house will be a temptation to the maids, and therefore a danger to morality. But of greater import, is Caterina’s romantic attachment to Captain Anthony Wybrow. Wybrow has wooed and won Caterina’s heart, but now Miss Assher is a prospect for marriage, and he reasons that he should follow Miss Assher and her mother to Bath to “win a handsome, well-born, and sufficiently wealthy bride”. The emotional anguish and torment that accompanies Wybrow’s decision, and Caterina’s assertion that he has led her on, are somewhat commonplace tropes of the romantic genre. But Eliot’s handling of Caterina’s fate, her furious desire for revenge, the circumstances that bring her to her decision to marry Gilfil, and her subsequent death, are handled with great skill by Eliot. Eliot raises the story above the conventions of romance through her use of the contextual backstory, as well as contextualising the story within the framework of Scenes of Clerical Life, as an expression of the dignity and importance of ordinary people.

Janet’s Repentance

The final story in Scenes of Clerical Life is the only one to name its female protagonist in its title. However, Charles Dickens had read only the first two stories when he wrote a letter to Eliot expressing his admiration and admitting that he thought ‘George Eliot’ was the pseudonym for a female writer. It is hard to imagine, now, that more contemporary readers did not guess that Eliot was a woman. Some suggested she might be a cleric. She didn’t make her authorship known until Joseph Liggins, a Cambridge-educated son of a baker, began to be credited with her work. Dickens had already expressed his suspicion in his letter to Eliot in January 1858: “I have observed what seem to me to be such womanly touches”.

Of course, from the perspective of a modern reader, some might argue that the gender and identity of the author is irrelevant. But Eliot did not readily conform to Victorian expectations of female behaviour or thought. She was interested in theories about evolution and she had come to question her religious faith. She stopped going to church and she lived openly with George Lewes who was already married with several children. This, coupled with her approach to her subject matter – ostensibly the private lives of people in a small English town, and the intersection of religion in their thought – colours her treatment of her fiction.

With Janet Dempster Eliot approaches her most problematic female protagonist. Janet is the wife of a local lawyer, Richard Dempster. Dempster is lauded among the men of the town for his ability to carry his liquor. In private, however, he is abusive. He beats Janet and belittles her. Janet, in turn, has begun to drink to numb the pain she feels in her marriage. The difficulties of the opening chapters have already been discussed, above, so I won’t mention them here. Reverend Edgar Tryan, the subject of religious division in the town of Milby, and the other man who is to become an influencing force in Janet’s life, has recently been appointed to his position. He is young, only thirty-three years old, and in poor health. Tryan’s age seems significant, since popular belief holds that Jesus was crucified at that age. And Eliot has him suffering with the slowly debilitating disease of tuberculosis, often associated with people of a higher moral or spiritual sensibility in the nineteenth century. In her book on the subject, Illness as a Metaphor, Susan Sontag writes:

For over a hundred years TB remained the preferred way of giving death a meaning – an edifying refined disease. Nineteenth-century literature is stocked with descriptions of almost symptomless, unfrightened, beautific deaths from TB, particularly of young people, such as Little Eva in Uncle Tom’s Canin and Dombey’s son Paul in Dombey and Son and Smike in Nicholas Nichleby, where Dickens described TB as the ‘dread disease’ which ‘refines’ death.

Susan Sontag, Illness as a Metaphor, Middelsex, England, page 20

Of particular relevance to Tryan, is Sontag’s observation:

As much as TB was celebrated as a disease of passion, it was also regarded as a disease of repression. The high-minded hero of Gide’s The Immoralist contracts TB … because he has repressed his true sexual nature; when Michel accepts Life, he recovers.

Illness as a Metaphor, page 26

In Tryan, we again perceive how Eliot interweaves themes throughout her three stories. Just as Amos Barton takes on a building project, so too does Sir Christopher. Further to that, Tryan is a version of Anthony Wybrow, if Wybrow had been tormented by his conscience. Tryan tells his personal story to Janet so as to break down the division between them that his position as a religious functionary may suggest to her. By doing this he is able to relate on a personal level that Amos Barton cannot. Tryan tells Janet that he had callously wooed and won the heart of a young lady, Lucy, and then cast her aside. He later learned that she fell into prostitution and eventually, death. Her death has brought about a change in him. He seems, now, sexless, and lives only to serve others as penance. As such, Tryan’s sickness is not moral, but an expression of the refinement of his soul.

And despite her alcoholism, Janet undergoes a similar refinement. A picture she drew years before of Christ’s suffering on the cross, seated over her mantelpiece, associates her lot with the suffering Christ. And while Tryan’s Evangelical ethos may reject the notion of ‘good works’ – that salvation might be earned – in favour of justification by faith alone, his own attempts to atone for sin, and the impression made upon him by his discovery, that Janet undertakes to help the poor without its generally being known, must impress upon us as readers that Janet’s redemption transcends the doctrinal divisions within the town, just as the death of Milly helps Barton overcome criticisms he has faced. Mrs Raynor, Janet’s mother, reads the story of the lost sheep, which is another representation of Janet: “the sinner that repenteth.” Her decision to trust Tryan and seek his help, despite her husband’s leading opposition of Tryan, is a healing moment both for the town and for her.

Modern readers may take issue with some aspects of Janet’s story. After all, this is a story about domestic violence, among other things. Richard Dempster is a truly horrible man, and modern thought would be that Janet would be best rid of him. So Janet’s thought, “Better this misery than the blank that lay for her outside her married home”, might be a moment for pause for many readers, as well as Janet’s heartfelt desire to forgive her husband. But we have to remember the economic reliance of women on men at this period of time, not to mention the vastly different attitudes to the social position of women, raised with a different mindset about their place in the world and their prospects. In addition to this, it is important for the purposes of the story that Janet does not appear opportunistic when she has a chance to rid herself of her husband. And more important than that, Janet’s redemption must be wholly complete, and the earnestness of her forgiveness cannot be in doubt, according to the Christian ethos she adopts. Naturally, different readers will make their own judgements about ‘Janet’s Repentance’.

By setting her dramatic representation of social divisions in the past, Eliot questions the ongoing social and religious divisions of society. It is an extremely subtle form of satire, which draws us in through the short form of her narratives, yet achieves depth and insight through her layered themes and motifs. In her first story, Eliot seeks to break down reader’s social prejudices against her narrative subject. In her last story, she tackles a problem not uncommon in Victorian England – that of abused women turned to alcohol – and shows that the ordinary story of an ordinary woman can reflect weighty religious themes on a human scale. This is why these stories remain interesting. Eliot progresses from the simple dichotomies and judgmental narrative voice of ‘Amos Barton’ to a more morally complex position over the course of her stories. As a woman who had lost her own faith, it is easier for modern readers to understand the Evangelical faith that raises Janet from alcoholism and despair, as a secular response to suffering. Tryan represents Evangelism within the town, but his ministering to Janet is on a human level that transcends doctrine.

Having decided to read all of Eliot’s novels, I thought I should begin with this collection of Eliot’s earliest writing first. My reading was undertaken with a sense of duty – something in the vein of background reading, I suppose – rather than enjoyment. But my experience of reading Scenes of Clerical Life was a pleasant surprise. I found that these stories were moving, entertaining, well written, and still very accessible.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!