Silas Marner is set in the past, approximately fifty years prior to the book’s publication. Like George Eliot’s first two novels, it focusses upon a rural community. Raveloe is a small village where the Industrial Revolution is yet to have any significant impact. The book’s characters are mostly ordinary folk with the Cass family at their head. Squire Cass is the local patriarch. The plot centres on Silas Marner, a weaver, a somewhat reclusive man, and Squire Cass’ two wayward sons. His first son, Godfrey, is in love with a village beauty, Nancy Lammeter, but he secretly has a wife and child whom he wishes to forget. His brother Dunstan, irresponsible and foolhardy, is blackmailing him. Eliot’s novel probes the notion of what makes a community, as well as traditional notions of status and class.

‘Merry England’

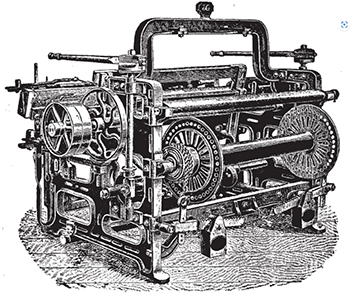

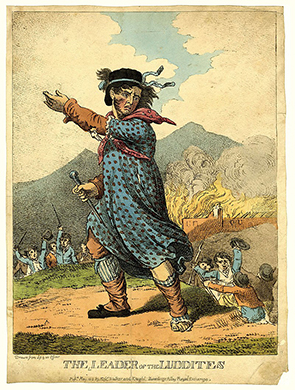

George Eliot’s setting for Silas Marner – an English village in the early 19th century – is significant. It is both a representation of social history as well as a carefully fabricated laboratory for her fiction. For instance, the word ‘Luddite’ does not appear anywhere in Silas Marner, yet it had been used in letters as early as 1811. In fact there is no allusion to this movement whatsoever in the novel, though it is set ‘in those war times’ of the Napoleonic era when the Luddites had become better organised ever since their early protests in the late 18th century. The Luddite movement was a reaction to the Industrial Revolution. Luddites threatened industrial owners and officials, and smashed machines they saw to be a threat to traditional skilled artisan work. Silas Marner is a weaver and weavers were particularly represented in the movement. In the English north, Weavers attacked steam-powered looms which allowed for the employment of unskilled labour and produced textiles at a far faster rate and greater volume.

Despite allusions to the historical context of her novel, George Eliot chooses to frame her story with a more nebulous temporal setting in her opening. The novel begins with the tone of a fairy tale, “In the days when the spinning wheels hummed …” She continues by writing of that “far-off time” when strangers were mistrusted, superstition was rampant and learning suspect. You could, on the face of this, be forgiven for assuming that this will be a tale about how much better things are now – for Eliot and her audience that was the 1860s – having overcome the benighted attitudes of parochial village life. But this isn’t so. Instead, Eliot has carved out a little piece of an older England to exist in tandem with the industrialising world around it: a place where everyone knows each other. The setting allows Eliot to explore moral issues through her narrative which she separates from traditional notions of class and religion, thereby creating a different environment in which to judge the quality of a person and the principles that guide them. Ravaloe, the village where Silas Marner lives, is a place “where many of the old echoes lingered, undrowned by new voices …” It lays on the,

outskirts of civilisation … in the rich central plain of what we are pleased to call Merry England … But it was nestled in a snug well-wooded hollow, quite an hour’s journey on horseback from any turnpike, where it was never reached by the vibrations of the coach-horn, or of public opinion.

Later, Eliot describes Ravaloe as a place,

aloof from the currents of industrial energy [where] the rich ate and drank freely, accepting gout and apoplexy as things that ran mysteriously in respectable families, and the poor thought that the rich were entirely in the right of it to lead a jolly life …

Even so, Silas Marner is a novel about change and a changing England. Late in the novel when Silas journeys to see the town he lived in thirty years before, where he was once a member of a religious community, he finds that the town is now cramped and stinking. Lantern Yard, the assembly place of his former religious community, has been replaced by a large factory.

Community change is not so dramatic in Ravaloe. The current story begins during Silas Marner’s fifteenth year in the village at a moment when his life is about to undergo a second great change. Fifteen years prior to the beginning, Silas was a member of Lantern Yard, working as an artisan within the religious sect. Silas was engaged to be married to a woman called Sarah, but Silas’ strange moments when he appears to be frozen or in a fit – Silas experiences catalepsy – perturb Sarah. Privately, she is no longer keen to marry Silas but she feels she has no means of legally breaking her engagement. That is, until William Dane, Silas’ friend, frames him for theft. Silas is excommunicated from the community after a peculiar ritual of drawing lots to determine his guilt or innocence, and Sarah is free to marry Dane. Silas’ reaction to this humiliation is somewhat predictable. Like his author, who rejected mainstream religion, Silas’ faith in the existence of a just God is shaken. Here we see parallels to the figure of Job, whose story can be used as a broad template for Silas’ own journey of loss and redemption.

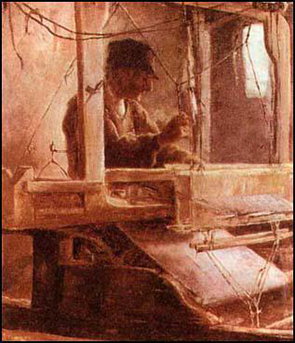

When Silas arrives in Raveloe, like many of those other “wandering men” who are mistrusted by the superstitious community, he keeps mostly to himself. Silas’ handiwork as a weaver makes him welcome for the richer housewives who come to rely on his craft, but he misses an opportunity to become a firm member of the community after he cures a woman the doctor has failed. Silas has been taught traditional medicines by his mother, but when the people of Raveloe turn to him for further help, he refuses to become involved. Instead, he spends his days at his loom in isolation, reducing his life to the “unquestioning activity of a spinning insect” in an “insect-like existence”. Through long years of labour and isolation he accumulates a large hoard of money with “no purpose beyond it.” Each day Silas spins at his loom, short-sighted and isolated, and each night he removes his coins from his hiding place in the floor to count them, like Potiphar counting his shekels.

Status and Class

The curing of Sally Oates, the woman Silas has healed through his knowledge of medicine, is one incident which, when teased apart, helps us to understand the broader function of the setting of the novel and its structure. Eliot tells us Silas, “had inherited from his mother some acquaintance with medicinal herbs and their preparation”. Silas’ skill stands in contradistinction to traditional medicine, represented by Doctor Kimble:

When Doctor Kimble gave physic, it was natural that it should have an effect; but when a weaver, who came from nobody knew where, worked wonders with a bottle of brown waters, the occult character of the process was evident.

Silas’ skill is on par with the Wise Woman at Tarley who had served the community until she died. Her treatments were akin to witchery, with muttered words and unorthodox treatments which seemed to work. “Silas Marner,” the villagers determine, “must be a person of that sort”, and they initially flock to him until he turns them away.

When compared to Doctor Kimble, we find that Silas Marner is not so different. Eliot points out that “country apothecaries in the old days enjoyed that title [of doctor] without authority of diploma.” In fact, Dr Kimble’s claim of being a learned man of medicine seems chiefly to reside in the fact that he looks and acts the part, along with village tradition: “Time out of mind the Raveloe doctor had been a Kimble; Kimble was inherently a doctor’s name”. So that, like Silas, who “inherited from his mother some acquaintance with medicinal herbs”, Dr Kimble is “welcomed everywhere as a doctor by hereditary right.” What we find here is that Eliot is subtly drawing attention to the question of status within the community and the way that orthodox social significations confer status and legitimacy. If this were the only instance, we might accept that it is a mere coincidence, but the novel is structured around parallel characters and situations which highlight the disparities of status, class and religion.

Another minor example, before I consider the story more broadly, is that of Squire Cass and Mr Osgood. Eliot introduces Squire Cass, perhaps somewhat ironically, as “The Greatest man in Raveloe”, yet she has already undercut him in the first chapter by suggesting that such greatness would be of no great thing: for the “practiced eye” would see,

… there was no great park and manor-house in the vicinity, but that there were several chiefs in Raveloe who could farm badly quite at their ease, drawing enough money from their bad farming, in those war times, to live in a rollicking fashion …

Of the “several chiefs”, Squire Cass’ claim to be foremost among them may be unchallenged in the minds of the villagers, but as readers we see that his elevated status is rather conditional. Eliot reiterates, “He was only one among several landed parishioners, but he was alone honoured with the title of Squire.” Mr Osgood’s family, for their part, have lived in Raveloe longer than anyone knows, and while Mr Osgood owns his farm, “Squire Cass had a tenant or two, who complained of the game to him quite as if he had been a lord.” Squire Cass’ social elevation seems arbitrary and marginal.

Already we see in these minor examples a distinction between the inherent quality of a character and the fixed types that populate the social framework of “Merry England”. Silas Marner may administer medicine as effectively as Dr Kimble – possibly more so – but he is not a doctor, while Kimble is accorded that status, though he holds no qualification, either. Likewise, Squire Cass may be no nobler than Mr Osgood or the Lammeter family, but by the traditional rules of English society he stands above them.

These dichotomies between families extends, too, into the past. Mr Lammeter, father to the pretty Nancy whom Godfrey, Squire Cass’ son, hopes to marry, is a second generation Lammeter in Raveloe. Nancy, despite Godfrey’s status as the son of the Squire, judges Godfrey harshly when she suspects his interest in her is going cold. “Did he suppose that Miss Nancy Lammeter was to be won by any man, squire or no squire, who led a bad life?” Nancy’s measure is the character of her own father, who has made a place in Raveloe despite their ‘Charity Land’, formerly held by the childless Cliff. Lammeter’s own father moved to Raveloe, like Cliff, and his industry and character have carved out a respectable reputation for their family. Meanwhile, Cliff’s story is a sad tale of thwarted social ambition. He moves to Raveloe with London pretensions, thinking he will be a gentleman, but neither he nor his son are accepted by the gentlefolk who laugh at them for aping their behaviours. Cliff refuses to acknowledge his own profession: he was a tailor. Eventually, he “died raving” after the death of his son, and his stables are subsequently thought to be haunted. There are distinctions being made here between hard work and pretension, between true character and the parvenu.

Parallels and Juxtapositions

This is Eliot’s strategy throughout, juxtaposing one character against another and running parallel plot lines within the controlled historical environment she has created in the village of Raveloe. When Silas’ hidden fortune is stolen one night we understand that this is a turning point in his life, just as was his moment in Lantern Yard when he was, himself, falsely accused of stealing. The theft, which happens early in the book, is not surprising, for it is hard to imagine the money he has accrued since he settled in Raveloe having any other purpose in the plot: Silas has no purpose for it other than to worship it. The first theft foreshadows the second. That the theft is conducted by Dunstan, the dissolute son of Squire Cass, however, is interesting: two thefts; two purported thieves. The reaction to each theft is demonstrative. Silas is accused and subsequently judged by a drawing of lots. Dunstan, on the other hand, after selling his brother’s horse to pay off a debt he has incurred, subsequently kills the horse in an accident before he can deliver it for payment, and so turns to Silas’ money in a moment of opportunity. That he disappears when the money is taken is not suspicious to anyone:

To connect the fact of Dunsey’s disappearance with that of the robbery occurring on the same day, lay quite away from the track of everyone’s thought – even Godfrey’s, who had better reason than any one else to know what his brother was capable of … his imagination constantly created an alibi for Dunstan.

Dunstan’s reputation is protected by his status in the community. Instead, the villagers fall back upon their own brand of prejudice and xenophobia. Someone thinks they saw a pedlar about. And from this one tenuous claim grows a detailed profile: “he had a swarthy foreignness of complexion”. By the time Justice Malam becomes involved (“he could draw much wider conclusions without evidence”) the pedlar is furnished in the imaginations of the villagers with curly black hair, carrying a box of cutlery or jewellery, with large rings in his ears.

It is easy to draw conclusions about prejudice and racism from this, but this would be missing the point, somewhat. We learn from the first page that pedlars, itinerant artisans and wandering men of all types are viewed suspiciously during this period in which the outside world is farther away and more mysterious. Contraposed to this is the notion of ‘neighbourliness’ which runs throughout the novel. When Silas comes to Raveloe he is a stranger, little understood by the community. He misses his opportunity to enter the life of Raveloe when he refuses to use his healing skills, and consequently spends fifteen years amassing a pointless fortune. It is clear to us that Silas is on a life journey with religious tones of redemption. I’ve alrady mentioned Job, but Eliot was also rereading Pilgrim’s Progress during this period of her life, and her character’s journey feels similarly imbued with a purpose approaching Christian’s, though his destination is somewhat different. For a start, Silas is moving away from traditional religion, even though he attends church in Raveloe for the sake of his adopted daughter, Eppie. Church and religion in Raveloe are somewhat more nebulous in their doctrines, which are imbued with the local character. Nancy has little formal education though “she had the essential attributes of a lady.” Dolly Winthrop, who encourages Silas to attend church, has no understanding of the letters she copies onto the cakes she bakes for Silas, except a belief that they must be good since she saw them on the pulpit cloth in church. And she practices a “simple Raveloe theology” of her own, in which Them above know better. Religion in Raveloe may be infused with superstition and flavoured by old local gods and beliefs, but it is a vibrant creed which brings the community together. That, after all, is the real point of encouraging Silas’ attendance at church on Sundays: that he be a part of the community.

Against this is the practices of Lantern Yard, Silas’ old sect, where a dissenting kind of Calvinism is practised which separates its adherents from the moral tenets of a community. They deem any effort to properly investigate the theft Silas has been accused of as “contrary to the principles of the church in Lantern Yard, according to which prosecution was forbidden to Christians.” This results in an erroneous judgment through a chance drawing of lots which is meant to represent the will of God. But it only calls into question God’s justice in Silas’ mind.

Transformations

The journey that Silas is set upon, however, is ultimately a secular journey. At Lantern Yard he lives in a community serving its own understanding of the divine. In the isolated “insect-life” he leads for fifteen years in Raveloe he engages in the hollow worship of mammon. His story, however, is still one of redemption and acceptance. Long hoping to have his gold returned to him, he enters his cabin one night to find a child there. It seems miraculous. With his short-sightedness, due to his years of close work at the loom, he first mistakes the child for his gold, returned: “to his blurred vision, it seemed as if there were gold on the floor in front of the hearth” but when he reaches down “his fingers encountered soft warm curls.” This is the real miracle at the heart of this novel, for the transubstantiation of the gold into the child is the catalyst for Silas’ transformation:

Thought and feeling were so confused within him, that if he had tried to give them utterance, he could only have said that the child was come instead of the gold – that the gold had turned into the child.

The child, Eppie, makes Silas sympathetic to the community for his willing sacrifice, and in time he finds his place as a neighbour. Against this are characters who fail their children – like Cliff – or fail to acknowledge their responsibilities as parents. The climactic confrontational scene between Silas and Eppie’s biological parent underscores a consistent theme within the novel: that class and status are not all, and that love and community are everything.

This may seem a trite summation of a complex and accomplished novel, but it is not a misrepresentation. The parallel journeys of Silas and Godfrey exemplify this, while the distance Eliot places between the “honest folk” of the village and their ‘betters’ deconstructs the significations of privilege and class. Silas Marner is a novel that implicitly asks us what we value. Raveloe is Eliot’s laboratory for experimenting with a hypothesis, like a science experiment that eliminates the variables that will taint its result. But the novel remains realistic. We are alive to the prejudices and failings of the “honest folk” who help redeem Silas, just as much as we understand that the historical moment is not really absent. When the Napoleonic wars threaten to end, the landed gentry panic that their easy earnings will wither. Even the Industrial Revolution is not entirely absent, for Silas’ earnings dwindle, too, over the years as less and less flax is spun by hand. Silas Marner is a novel about transformation and change, after all. But it is a novel about personal change just as much as it documents the changes in society for Eliot’s audience.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!