Adam Bede is George Eliot’s first novel. It was published in three volumes in 1859, following her three novellas, ‘The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton’, ‘Mr Gilfil’s Love-Story’ and ‘Janet’s Repentance’, each serialised in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine in 1857, and later published as Scenes of Clerical Life. Like Eliot’s previous work, Adam Bede is set in the past, sixty years prior to the book’s publication, and focusses upon a rural community, Hayslope, where the Industrial Revolution and Enlightenment thinking are yet to have any significant impact. Its characters are farmers, carpenters, country squires and Methodists. Hayslope represents a country idyll essentially lost to the experience of Eliot’s contemporary readers, and therefore provides Eliot with a counterpoint to her own times, an essential feature of this work.

While Adam Bede tells the story of its titular character’s progress towards love, modern readers may have more interest in the story of Arthur Donnithorne and Hetty Sorrel. Stories of forbidden love and tragedy are inherently more interesting, while Adam’s slow drift towards Dinah Morris, a Methodist preacher who has devoted her life to the service of God, may feel a little harder to get excited about these days.

In fact, criticisms I have read of this novel have focussed on its slow pace. Judging from the style of many novels today, readers may have expectations of fiction which will not be fulfilled by Adam Bede. Modern novels often begin in media res, or at least focus on the most salient aspects of the story from the start. Advice on how to begin a story often includes the direction to begin at a pivotal moment. Readers have to be ‘gripped’, ‘hooked’ or be drawn in by some equally violent metaphor to ensure their attention. With so many options for entertainment and demands on our time, a book has to justify its existence in our lives fairly quickly.

A Pastoral Melodrama

However, when George Eliot wrote Adam Bede, she clearly didn’t intend that her readers should only be interested in the plot. If Adam Bede had nothing to offer except a story, it would be little more than melodrama.

As a story, Adam Bede is basically a pastoral melodrama about a way of life and ways of thinking that will be quite beyond the experience of many readers today. Most of the novel centres on the fate of Hetty Sorrel, a milkmaid who works for Mr and Mrs Poyser at Hall Farm. She is tasked with churning the butter in the dairy and is an extremely attractive seventeen year old. Her seduction by Arthur Donnithorne, grandson and heir of the local squire who is landlord of the properties in the county, provides the narrative drive. Adam Bede, a hardworking carpenter in the employ of Jonathan Burge, a builder, has not the resources to marry Hetty yet, but he has his hopes set on her and everyone in the community believes it is only a matter of time before Adam will be financially capable of supporting a wife. Arthur, who is expected to marry within his class, is rash to pursue Hetty and acts unfairly by inflaming her hopes for a future as his wife. This is the standard stuff of melodrama, especially since the plot progresses with customary tropes: of false promises and deception; of broken friendships and conflict; of abandonment and even murder.

A Mirror Held to the Past

Yet this is not where the novel starts. Eliot allows her plot to unfurl at a leisurely place. We begin in Adam’s workshop, and then progress to a sermon by a female preacher, Dinah Morris, in the next chapter, and in the succeeding chapters we learn about Hayslope and its inhabitants as we see the first hints of Hetty’s seduction. The most dramatic event in the first quarter of the novel is the discovery of Thias Bede, Seth and Adam’s father, drowned in a brook. Yet the moment has little consequence in the plot and Adam seems somewhat relieved to be rid of his alcoholic father. The novel progresses at the pace of late eighteenth century rural community life.

And yet, a sense we sometimes feel in our modern world – that the pace of life is just a little too quick – is not alien to Adam Bede. Eliot reveals this by reflecting upon the lives and times of her characters in the context of her own milieu. Eliot talks directly to her readers whom she expects to be sophisticated, with at least a vicarious understanding of subjects of the heart gained from their reading. After all, her readers must be more sophisticated than Hetty Sorrel whom, we are told, “knew no romances, and had only a feeble share in the feelings which are the source of romance, so that well-read ladies may find it difficult to understand her state of mind.” Eliot’s readers are asked to make a comparison between the pace of their own lives and that of her characters’. Towards the end of Adam Bede Eliot’s narrator interrupts the story to lyricise upon the simple pleasures now lost to the nineteenth century:

Leisure is gone – gone where the spinning-wheels are gone, and the pack-horses, and the slow waggons, and the pedlars, who brought bargains to the door on Sunday afternoons. Ingenious philosophers tell you, perhaps, that the great work of the steam-engine is to create leisure for mankind. Do not believe them: it only creates a vacuum for eager thought to rush in.

Adam Bede, Chapter 52: Adam and Dinah, page 583

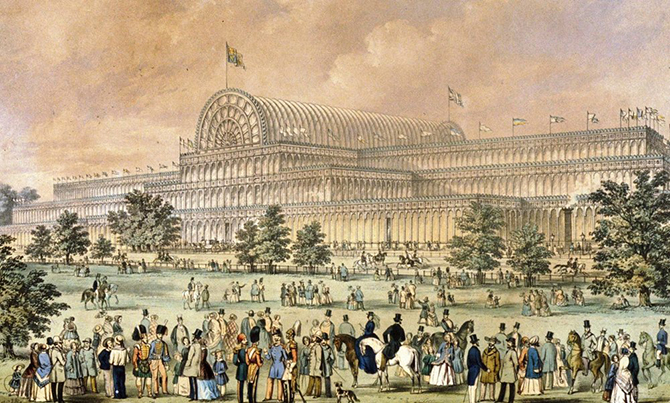

Eliot characterises the pursuits of contemporary leisure as, “prone to excursion-trains, art-museums, periodical literature, and exciting novels: prone even to scientific theorising, and cursory peeps through microscopes”. The Industrial Revolution and the Enlightenment had introduced changes in thought and public entertainment to Britain in the 1850s. The Great Exhibition held in the Crystal Palace in London in 1851 had been attended by millions of people and showcased all that was best and astonishing in the progress of industry, culture and science. It was an intellectual flexing of the country’s muscle; a showcase for the might of the British Empire, and a signal that life had changed irrevocably.

In contrast, Eliot imagines a personification of leisure at the turn of the century from the old pastoral world – ‘Old Leisure’ – who is a man content to read only one newspaper, sleep through church services, and is happy not to understand the world around him. ‘Old Leisure’, “lived chiefly in the country, among pleasant seats and homesteads.” ‘Old Leisure’ represents that atavistic yearning for nostalgia, for the safety of simplicity, and a belief in a moral world now lost. When we begin to understand this, even if we do not agree with the sentiment, we understand more clearly the pace of this novel, which insists we get to know its people and their lives before we embark on the more salient features of its plot.

So, rather than starting the story with the most pressing aspect of her drama, Eliot chooses, instead, to create a scene. This is the opening paragraph of the novel:

With a single drop of ink for a mirror, the Egyptian sorcerer undertakes to reveal to any chance comer far-reaching visions of the past. This is what I undertake to do for you, reader. With this drop of ink at the end of my pen, I will show you the roomy workshop of Mr. Jonathan Burge, carpenter and builder, in the village of Hayslope, as it appeared on the eighteenth of June, in the year of our Lord 1799.

Adam Bede, Chapter 1: The Workshop, page 1

It is a deceptively simple opening which establishes several aspects of Eliot’s purpose immediately. She gives an exact date, so her contemporary readers knew from the start that this was a tale about the past. But in performing the function of the ‘Egyptian sorcerer’, Eliot is already mythologising that past, making it exotic and desirable. Added to that, she is creating a relationship with her reader which she will maintain throughout the novel. Eliot’s narrator often interrupts the flow of the story. In chapter 17, called ‘In which the Story pauses for a little’, Eliot’s narrator discusses her approach to her subject matter. In other places, she offers comments upon her characters, remarks upon thematic aspects of the story, or simply draws us into a scene. In chapter 6, ‘The Hall Farm’, for instance, her narrator tells us that “imagination is a licensed trespasser”, and encourages us to put our face against the pane of glass of the Poyser’s household window, as though we are there with Eliot, being led on to mischievously peek into the private life of her characters. Similarly, when we are introduced to the Rev. Adolphus Irwine, Eliot offers, “Let me take you into that dining-room”, and suggests, “We will enter very softly, and stand still in the open doorway”. So, another interesting aspect of the opening is that Eliot transforms the drop of ink suspended from her pen into a mirror for the past; a conduit through which we enter the workshop and see the men as they finish their work for the day. Already we have the sense of exterior and interior: the boundaries between private and public worlds; but also, as we enter the narrative, we see it is a ‘mirror’ held to a past as a foil to Eliot’s contemporary England.

Hetty Sorrel and Dinah Morris

The notion of a narrative mirror is a strategy which finds its equivalent in the character of Hetty Sorrel. Hetty is associated with mirrors and reflections throughout the novel, and Eliot structures her plot around characters who reflect each other in the manner that mirrors do: as reverse images or contrasts. Hetty is vain and acquisitive. She admires herself in mirrors constantly: she dislikes the mirror in her room because blotches on the old glass mar her reflection. Her vanity has been noticed by Mrs Poyser, who chastises her distracted nature, suggesting Hetty could spend as long as “two hours by the clock” to dress herself. And Hetty likes the good things of life. This is a part of Arthur’s attraction. He is able to provide her with trinkets she admires, like the locket he gives as a present. When Arthur’s attentions put it into her head that she may one day be his wife and a lady, Hetty is filled with thoughts of her future life. Adam may be better looking and a more impressive man, but Arthur will be able to give her a life she can never have with Adam.

Eliot creates a counterpart to Hetty in the figure of Dinah Morris. Dinah is a Methodist preacher who comes to Hayslope to preach in the second chapter. The idea of a female preacher in this period may seem far-fetched, but Eliot is on solid historical ground. Methodists practised strict religious observance (although Eliot is at pains to point out how even Methodists in her own time are not so well thought of). Mary Fletcher, who is twice alluded to in the novel, persuaded John Wesley to allow women to preach. Fletcher was one of a number of female Methodist preachers servicing working class people who may otherwise not have been ministered to: as in the scene in chapter 2 in which Dinah comes to Hayslope to preach, they often performed outdoor sermons. Dinah, we discover, like Hetty, is attractive, and while that draws interest from some of her male congregants, it is of no consequence to Dinah. Where Hetty is vain, Dinah is demure. Where Hetty is acquisitive, Dinah eschews material possessions. She even rejects the idea that she might marry because it would interfere with her calling. Hetty and Dinah are an example of the dichotomies that underlie the novel: the former vain and worldly, the latter devoted to service and God.

Adam Bede and Arthur Donnithorne

Similarly, Adam and Arthur form a contrasting pair. In the opening chapter, we see that Adam plays an authoritative role in the workshop. Adam objects to the men dropping their tools as soon as the church clock strikes six. He is a serious fellow, we find, driven by strong religious and moral convictions, whose notions of work are closely aligned to his religious beliefs. He tells the workers,

Why, it says as God put his sperrit into the workman as built the tabernacle, to make him do all the carved work and things as wanted a nice hand. And this is my way o’ looking at it: there’s the sperrit o’ God in all things and all times – week-day as well as Sunday – and i’ the great works and inventions, and i’ the figuring and the mechanics. And God helps us with our head-pieces and our hands as well as with our souls; and if a man does bits o’ jobs out o’ working ours – builds a oven for’s wife to save her from going to the bakehouse, or scrats at his bit o’ garden and makes two potatoes grow instead o’ one, he’s doing more good, and he’s just as near to God, as if he was running after some preacher and a-praying and a-groaning.

Adam Bede, Chapter 1: The Workshop, page 6

Adam’s morality and sense of self-worth derive from his work and the good he can do others. Ironically, his ideals align fairly closely to the Methodist principles held by Dinah, but he shows little interest in them. In chapter 17, Adam Bede, in his old age, speaks to George Eliot about the religious ideas circulating in the village in his earlier days. Adam rejects the idea of the intellectual tenets of theology, and trusts, rather, to ‘feelings’: “It’s notions sets people doing the right thing – it’s feelings”, he explains. To clarify his point he makes a comparison between mathematics, which is theoretical, and engineering, which is practical: “to make a machine or a building, he must have a will and a resolution, and love something better than his own ease.” Adam’s morality is a working-man’s understanding of doctrine, which he sees as merely, “finding names for your feelings.” Adam decides he cannot understand the religious arguments between Arminian and Calvinist Protestants, and so decides to trust in the wisdom of Rev. Irwine, instead, who, “said nothing but was good.”

Religious Tenets

These religious positions split the Protestant church, including Methodism, and Eliot’s foregrounding of them suggests they may help in understanding the broad purpose of her story. John Wesley rejected Calvinist tenets of predestination and instead supported the Arminian doctrine, which caused a rift between him and his collaborator, George Whitefield, who continued to support Calvinism. Arminianism held, like Calvinism, that people were ‘depraved’, but instead believed in the idea of ‘perfectibility’ (although improvement would be a better word, I think). While adherents of Arminianism maintained that election to salvation is conditional upon faith (as opposed to unconditional election under the Calvinist doctrine which posits an inscrutable God), the popular notion of election by perfectibility through good works has also been an aspect of popular Arminian belief. Dinah, who is a follower John Wesley – she describes having seen him as a little girl – lives a life of good works and devotion to her calling. Like Adam, she works hard, apart from her preaching. She tells her congregants in Hyslope, “I am poor, like you: I have to get my living with my hands.”

Adam, too, is characterised by this popular belief in the importance of work to a man’s worth. Eliot reinforces this repeatedly throughout her novel. Adam tells Dinah,

. . . a man must have courage to look at his life so, and think what’ll come of it after he’s dead and gone. A good solid bit o’ work lasts: if it’s only laying a floor down, somebody’s the better for it being done well, besides the man that does it.

Adam Bede, Chapter 50: In the Cottage, page 550

Adam’s work ethic eventually pays off. Though he will not marry Mary Burge, his boss’s daughter, he has become so indispensable that Burge will offer him a part in the business, anyway. In another authorial aside, Eliot tells us that men like Adam Bede, while forgotten by history, make a difference to their communities through their work: that when they die, their employer wonders “Where shall I find their like?” It is a wistful question that belies a yearning for a lost past.

Arthur Donnithorne, on the other hand, despite his desire to do good for his future tenants, and despite the fact that Adam admires him as his social superior, provides a contrast to Adam. When he jokingly suggests to Mrs Poyser that he might one day move into the farm, she tells him, somewhat alarmed, that running a farm is not as easy as he might suspect: certainly not the kind of life he imagines. Farming, to Mrs Poyser, “it’s raising victual for other folks” with risks of losing money, and not in the fun way that “the great folks i’ London play at more than anything.” Mrs Poyser’s implicit criticism is obvious. Arthur’s social position and lack of any real responsibility allows him to imagine a future and good works divorced from the realities of doing anything. While Eliot, over and over, impresses us with Adam’s good works, she constantly impresses upon us that Arthur has good intentions.

Like Adam, Arthur is not the kind of intellectual to be consumed with theoretical positions, nor is he burdened by any personal philosophy more considered than a desire to be popular. Yet Eliot neither allows him to be wholly good or bad, in keeping with her principle that, “There are few prophets in the world; few sublimely beautiful women; few heroes”. To understand Arthur’s role in the novel I think it is also important to consider Eliot’s moral purpose. Arthur may have been the villain at the hand of another writer, but Eliot represents his human frailties and weaknesses just as much as Hetty may be said to be his victim; even though she contributes to her fall and we disparage her vanity. Eliot’s position is a sophisticated balance between antithetical doctrines, characters and values, while at the same time adhering to a realistic understanding of human nature. Arthur has a strong belief in his own god intentions because they have never yet been tested while ever he is has been in his minority and his grandfather is alive. But Eliot shows through Arthur’s seduction of Hetty that there is a difference between good intentions and good actions:

There is a terrible coercion in our deeds which may first turn the honest man into a deceiver, and then reconcile him to the change; for this reason – that the second wrong presents itself to him in the guise of the only practicable right.

Adam Bede, Chapter 29: The Next Morning, page 354

Intertextual References

Eliot further suggests these inconsistencies through her intertextual references which serve no purpose unless they tell us something about character. When Arthur is sent “a parcel” containing a copy of Lyrical Ballads – it was only published the year before in the timeframe of the story – Arthur calls it “twaddling stuff”. Of course, in Wordsworth’s Preface to the Lyrical Ballads he outlines the principles upon which the poems are written:

The principal object, then, which I proposed to myself in these poems was to choose incidents and situations from common life and to relate or describe them, throughout, as far as was possible, in a selection of language really used by men . . .

Preface to Lyrical Ballads, William Wordsworth

Arthur does not relate to Wordsworth’s poetry, even though it dignifies the poor whom Arthur has promised to serve, but he is drawn to Coleridge’s ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. “It’s a strange striking thing,” he tells Rev. Irwine, even though he, “can hardly make head or tail of it as a story”. As readers, even if we don’t understand at a first reading, we understand it by the end of the novel, that like the mariner shooting the albatross, Arthur will be set to wander the world for a wrongdoing.

Typical of some passages in Eliot’s writing, she is achieving several things in a paragraph. She is characterising Arthur here, but she is again telling us about the principles by which she writes. After all, an extract from Wordsworth’s poem, ‘The Excursion’, provides the epigraph for the novel, and when she writes about her intentions for her fiction in chapter 17, her principles for writing seem closely aligned with Wordsworth’s:

. . . do not impose on us any aesthetic rules which shall banish from the region of Art those old women scraping carrots with their work-worn hands, those heavy clowns taking holiday in a dingy pot-house, those rounded backs and weather-beaten faces that have bent over the spade and done the rough work of the world – those homes with their tin pans, their brown pitchers, their rough curs, and their clusters of onions. In this world there are so many of these common coarse people, who have no picturesque sentimental wretchedness! It is so needful we should remember their existence, else we may happen to leave them quite out of our religion and philosophy, and frame lofty theories which only fit a world of extremes.

Adam Bede, Chapter 17: In Which the Story Pauses a Little, pages 200 - 201

This speaks to Eliot’s desire, as an artist, to produce social realism; a desire she has already addressed in ‘Mr Gilfil’s Love-Story’. In chapter 17 of Adam Bede she characterises this rustic life through the example of Dutch paintings. John Ruskin, an art critic and famous intellectual of Eliot’s period, had characterised Dutch paintings as lacking poetry. They were not held in high regard during the 1850s. Their subject matter was common people in ordinary moments of their lives. But Eliot had seen a collection of Dutch paintings in Munich in 1857, which is where she actually wrote chapter 17. Eliot wrote:

I delight in many Dutch paintings, which lofty-minded people despise. I find a source of delicious sympathy in these faithful pictures of a monotonous homely existence, which has been the fate of so many more among my fellow-mortals than a life of pomp or of absolute indigence, of tragic suffering or of world-stirring actions.

Adam Bede, Chapter 17: In Which the Story Pauses a Little, page 199

So many scenes in Adam Bede resemble the aesthetic style of Dutch painting. The opening scene in the workshop is described in the manner of a Dutch painting, with the dramatic entry of the sunbeams through the window that shine “through the transparent shavings that flew before the plane.” Not only did Eliot like Dutch paintings, but they provided her with the rural aesthetic which would dignify her working class characters.

Arthur’s Moral Failure

Eliot’s desire to present people in the full reality is also why Arthur cannot wholly be a villain in her melodrama. These rustics she speaks of are the kinds of people Arthur is determined to help when he becomes squire of the county, and the anticipation of this future situation which will make Arthur popular among the villagers. But Arthur’s motivations are not of the kind that drive Adam to do good works. Rather, he fantasises over his own his popularity in a way that is similar to Hetty’s enamoured gaze at her own beauty:

I shall be the ‘old squire’ to those little lads and lasses some day, and they’ll tell their children what a much finer fellow I was than my own son.

Adam Bede, Chapter 22: Going to the Birthday Feast, page 288

Arthur’s benevolence is self-serving and vain. After the death of his grandfather his mind is filled only with the good works that he might now perform, which will provide him with the opportunity of being at the centre of community life to be loved by all: “a jolly fellow that everybody must like, - happy faces greeting him everywhere on his own estate, and the neighbouring families on the best terms with him.”

Arthur is not essentially a bad man, but Eliot has the means to turn our thoughts to the construction of her argument through her characterisations. For instance, in that parcel Arthur received in London was also included, “pamphlets about Antinomianism and Evangelicalism”. Again we have conflicting religious doctrines, like Calvinism and Arminianism. Again, it would be an odd detail to slip into the story for no purpose, given Eliot’s intrusions into the narrative to discuss religious and moral ideas at other moments. Antinomianism asserts that those who have faith are not bound by earthly rules and laws, since their election to salvation is through faith alone. Methodism was an Evangelical movement. John Wesley called antinomianism the “worst of all heresies” and insisted on following the moral law of the Ten Commandments. Arthur, like Adam, rejects doctrines which are merely “finding names for your feelings”. “I’ve written to him to desire that from henceforth he will send me no book or pamphlet on anything that ends in ism,”he tells Rev. Irwine.

Nevertheless, while Adam’s principles of work can be likened to Arminian theosophy, which is further reinforced by his slow drift towards Dinah, Arthur’s faith lies in his own goodness. Yet Eliot warns us of Arthur’s moral weakness:

Whether he would have self-mastery enough to be always as harmless and purely beneficent as his good-nature led him to desire, was a question that no one had yet decided against him; he was but twenty-one, you remember, and we don’t inquire too closely into character in the case of a handsome generous young fellow, who will have property enough to support numerous peccadilloes—who, if he should unfortunately break a man’s legs in his rash driving, will be able to pension him handsomely; or if he should happen to spoil a woman’s existence for her, will make it up to her with expensive bon-bons, packed up and directed by his own hand.

Adam Bede, Chapter 12: In the Wood, pages 139 - 140

He can convince himself that he remains good even when his actions must be hidden from society because he would cause a scandal if they were exposed. This is a kind of secular antinomianism, because Arthur’s belief in himself, and the privilege that his social position and wealth afford, have cut him loose from ordinary moral precepts when he fails to resist the temptation that Hetty provides.

Concluding Remarks

Eliot’s novel, on the face of it, would seem primarily to be a melodrama about seduction, deception and a terrible crime. But she balances this story with the far milder tale of the slow movement towards love between Adam and Dinah, as well as the values these characters represent in the context of Eliot’s modern world: of old-fashioned Christian virtues; a belief that suffering eventually makes joy more intense; that work and service dignify an individual and their community. There is a sense of a slower world in which individuals who take the slower way are rewarded for their patience. In contrast, we see that beauty is not necessarily a sign of a moral soul, and while remaining faithful to moral principles can be difficult, there is a danger in accepting moral failure.

Some will find they don’t like the slow unfolding of this story, but I did. For me, a simple melodrama would have merely been salacious and obvious. But Eliot’s novel is sophisticated and thoughtful, even if it is possible to criticise its awkward ending, which is too subtly suggested through Dinah’s blushes earlier in the novel, and a little contrived: or that too little is made of Hetty’s fate: or that some aspects of the story, like the death of Adam and Seth’s father, Thias, remain underdeveloped. This is a novel about characters and ideas. And, I must admit, I also enjoyed the pastoral world of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century England as Eliot imagined it. It’s a simpler world that some of Eliot’s contemporary readers, at least, must have longed for. As twenty-first century readers, it’s still a world we may find escapist comfort in, too, if we are patient.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!