Note: I received a copy of The Strange Death of Paul Ruel from the author. However, my opinion expressed in this review and links to the author’s website are made at my own discretion. Michael Duffy had no input or influence in the writing of this review.

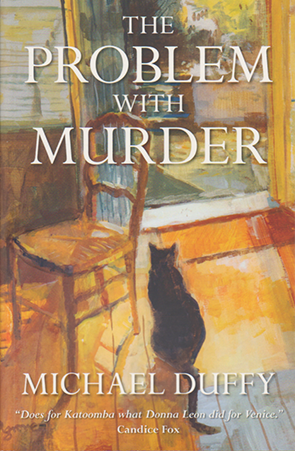

Michael Duffy’s second offering in what is now being called the Bella Greaves Series, is a worthy sequel to the original. Its story is equally as compelling, as are its characters, including the backdrop of the Upper Blue Mountains, itself. The Strange Death of Paul Ruel achieves a similar atmosphere as The Problem with Murder, with the rugged Mountains landscape and its unpredictable weather a key feature in the story.

As the novel begins, Paul Ruel remains an outsider to the culture of the Blue Mountains Police force after only seven months in his new position. There has been a social event for a sick colleague but Paul is not invited. He doesn’t fit in and his past fame is merely a source of jealousy. Having enjoyed semi-celebrity as a homicide detective in Sydney, Paul had been transferred to Katoomba Police station after a media gaff gave his superiors a reason to banish him.

So when a body is found at the base of Govett’s Leap, a 180 metre tall pencil thin waterfall disgorging into the Grose Valley out of Blackheath, Paul’s thorough investigation of the circumstances of the death is seen as a symptom of his desire to recapture his past relevance and purpose. When he subsequently rescues a young drug-affected woman, Hannah, from the top of the cliff, YouTube videos of the event raise the status of the case and once again give Paul some notoriety.

And when Paul and his family begin to suffer a series of mishaps, he turns to the only person he feels he can confide in, Bella Greaves. Bella is a former Sydney Morning Herald journalist who meets with Paul at a local café where they sometimes discuss his cases. Bella provides advice for Paul as well as investigative backup. She is a two time winner of the Walkley Award, the highest recognition of excellence for Australian journalists. Like Paul, Bella has performed at the top of her field, and her intellect and talents are underutilised working for Katoomba’s local newspaper.

As incidents continue to affect Paul and his family, Paul begins to fear for their safety. His former wife has had her car brakes fail, his father has had a fire in his home, and Paul is plagued by accidents himself. Paul thinks an inmate from Lithgow Prison is directing others against him in revenge for his incarceration. But Bella thinks Paul is becoming paranoid and his colleagues dismiss his concerns. However, when Paul Ruel disappears, feared murdered, the investigation is taken seriously and the connections Paul and Bella have been making between the circumstances of the night of Michael Rossi death at the bottom of Govett’s Leap and evidence of a clandestine development begin to coalesce.

Duffy’s narrative, as before, relies not on sensation, but the mystery of the situation he creates and the curiosity he provokes in his reader. The manner of Michael Rossi’s death seems like a fulfilment of a potential from the first novel, of the latent sense of threat that abides in Duffy’s landscape: of the fog-filled valleys and vast emptiness beneath the mountain settlements that invert the normal human relationship with nature, offering an easily accessible death.

The sense of place in The Strange Death of Paul Ruel continues the associations made in The Problem with Murder. But Duffy extends the significance of place in this novel. For instance, some seemingly incidental additions to the book feel more consequential as you read. First, is a basic map of the Upper Blue Mountains Plateau, which will be useful for readers less familiar with the area. Second, is the acknowledgement of the area’s traditional owners on the map, the Darug and Gundungurra people. The stories Aboriginal people told of their world, known as Songlines, are an articulation of a connection between culture and the land, between people and the wilderness. Bella’s Memory lane column in the local newspaper also mixes fact and fiction, annoying some readers, even though it is, in essence, a vague continuation of the tenets of traditional culture. Much of the import of this novel is concerned with that uneasy relationship between Western culture and landscape. The sense of it is peppered throughout the book. Valleys are described as vast emptiness, like a negation of the human world. And residents live adjacent to rather than with the natural world. There is a wonderful vignette of a woman – “a Katoomba phenomenon” – with her shopping and child:

Despite the weather, she was wearing just a skimpy top – almost a bikini – and shorts and thongs. She half ran, so she must have been cold, but the idea of putting on more clothes was clearly unappealing. Paul had seen it on call-outs: many locals lived in heated homes during winter and simply ignored the weather, going outside as rarely as possible. When they did, they drove everywhere in heated cars, to heated shops or pubs, and pretended the cold didn’t exist. They were in the Mountains, but not quite of them.

Duffy’s allusions to landscape is not new in Australian film and writing: Western culture continues to have a problematic relationship with its environment, a fact reflected in references to climate change in the novel. But the writing is not echoing current calls to climate activism, which is really the purview of Jenny Perkins, a local Letters to the Editor contributor who plagues Bella Greaves. Instead, it speaks to issues of identity and a relationship to our world.

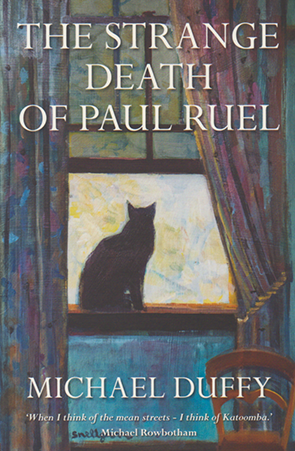

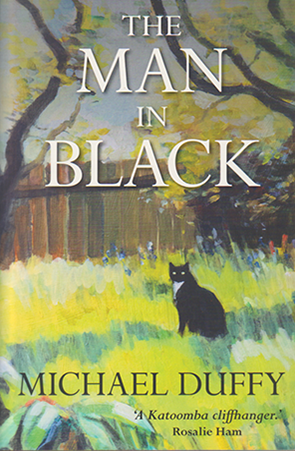

So, while the crime story cracks along and becomes more and more intriguing, with clues unfolding of corrupt dealings extending to State politics, and the action increases and so do the stakes for the protagonists – in short, this reads like a crime story a fan of crime fiction will want to read for the crime fiction, itself – there is a sense behind the story that there is more to appreciate here. It’s possible to start joining dots and wondering about what initially seems like minor details. To start with, there’s a little bit of blatant marketing at one point. Bella tells her daughter about a series of cards by a local artist called Alex Snellgrove. The artist in real life is Duffy’s wife and the cards mentioned are available at the time of writing from the Hydro Majestic in Medlow Bath and online at michaelduffy.com.au. Her art is also used for the covers of The Problem with Murder and this book. But then Siobhan, Bella’s daughter, is a trained artist too, and her commission to paint a mural for Editions of You, Hannah’s clothing store, is significant, as is the place of art and artists in the novel. Duffy is keenly aware of the importance of creative people, be they musicians or other artists, who inform our sense of our world. And like the Aboriginal Songlines, art is a potential nexus between humans and the natural world they inhabit.

Key to this, I think, is a sense of a Mountains identity. While not mentioned in Duffy’s story, places like Everglades in Leura, (featuring beautiful gardens and used as an artists’ retreat), Norman Lindsay’s Gallery in Faulconbridge (and featured in the film Sirens starring Hugh Grant and Sam Neill), or Reg Livermore, an actor and artist who used his mountains property as an artistic retreat, have helped to forge a community identity separate to Sydney. In opposition to this is the threat of unsympathetic developments, like the Crown Casino built by James Packer in Sydney, dubbed ‘Packer’s Penis’ for its hubristic domination of its local environment. Apart from telling us a good crime story filled with the moral ambiguity of modern crime fiction, Duffy is also doing this: he is considering a Mountains identity and how we form a sense of self through our connection to a place. Duffy has Bella say, “For a place to be truly meaningful, it needs a history as well as landscape. I’m trying to give the Mountains a little human depth.” Like the allusion to his wife’s work, Duffy may well have been saying the same of his own writing.

The Strange Death of Paul Ruel, like The Problem with Murder, is only available from Blue Mountains bookstores. However, it can be purchased online from michaelduffy.com.au Follow this link to check it out.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!