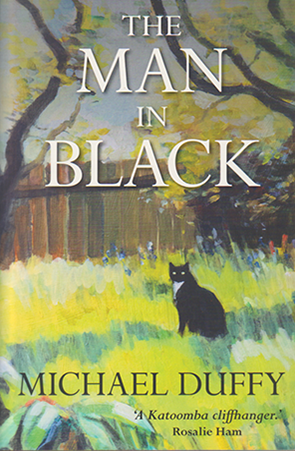

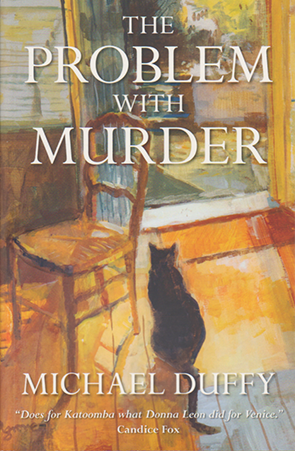

The Man in Black is Michael Duffy’s third instalment in the Bella Greaves Series set in the area we live, the Blue Mountains west of Sydney. Bella Greaves is a late fifty-something newspaper editor for a local Mountains paper based in Katoomba, one of the largest and most famous suburbs in the upper-Blue Mountains, overlooking the Jamison Valley. In the first book of the series, The Trouble with Murder, Bella forms a friendship with a recently-arrived Sydney detective and minor celebrity, Paul Ruel, after he is forced into the relative obscurity of a Mountains posting. By this third book Paul and Bella have history. In the second book of the series, for instance, The Strange Death of Paul Ruel, they conspire to fabricate details of Paul’s disappearance in order to get the bad guy. In this third novel, that history creates some tension in their private lives. Paul hasn’t told Siobhan, his partner (and Bella’s daughter) of their subterfuge: the need to protect a witness before that case goes to trial and to keep their secret will place a strain on their relationship.

This third outing for Bella Greaves and Paul Ruel extends now-familiar themes in the series. Katoomba, a township sitting atop the Jamison valley in the upper-Blue Mountains, is the primary setting for this novel. It is a place steeped in fog and rain, and home to many who come to the Mountains to connect with its wild landscape; some, even, to end it all with a despairing leap from Katoomba’s cliffs. While Duffy’s stories are primarily crime fiction, they are imbued with a sense of place, community, and the encroaching pressures of modernity: touching on the climate crisis; on the role of media in the modern world; on the struggle for personal fulfilment. Each book also touches upon the hidden physical and even sexual violence that can shape and unmake lives in a community.

This third novel begins with accidental violence. Melisse Chen, fleeing a women’s refuge in Cowra with her children to escape her domineering husband, collides with Liam Tarrant’s truck just outside the Hydro Majestic. Liam is also the victim of domestic violence at the hands of his father growing up, as well as sexual abuse by an uncle. His life has been a mess, involving drugs and petty crime. He was once Paul Ruel’s informant, but he was deemed too unreliable. Now, Melisse Chen claims Liam Tarrant crossed the line in his truck. Her three-year-old child is dead. Liam contradicts Melisse’s version of events. To everyone’s surprise, the facts seem to back Liam’s version of the accident.

The direction of the novel seems set.

But Duffy’s narratives are never mono-linear. The terrible tragedy of the highway accident is the merely the catalyst for Liam Tarrant’s branching story. Liam Tarrant, with the threat of a manslaughter charge over him, suddenly accuses a local priest, Father Brian Kelly, of sexually abusing him as a child. On the surface, his motive seems transparent: to deflect attention and gain sympathy. Father Kelly has only returned from Africa a year before after a long absence. He’s been haunting the lookouts over the Jamison Valley at night since then, occasionally talking jumpers down. Now, Liam claims to have recognised him while contemplating suicide at one of the lookouts. Kelly is about to gain unwelcome notoriety.

Bella, for her part, is facing a crisis of her own. A tree has collapsed in her yard, damaging a window of her house. Her funds are meagre and her plans for her retirement uncertain. Added to this, Jenny Perkins, the climate activist and incessant letter-to-the-editor writer of the first two books, has started her own newspaper, The Independent, as a result of a comment made by Bella. Jenny’s newspaper is expensive and has a small circulation, but it is drawing vital advertising dollars from Bella’s paper, and Bella’s new boss, Amber (the circulation boss’s granddaughter), is pressuring Bella to run climate stories, too, even though they’re not typical fodder for local news. When the story of Liam’s accusation begins to emerge, Bella is placed under further pressure to print details of Liam’s claim, as well as name Kelly. Bella is in a fix. It would be against Bella’s journalistic standards, since doing so could prejudice the case. Her job is on the line.

What is unusual about reading this series of novels, is that Duffy is often focused more on his characters’ lives and their community, rather than advancing a standard crime story. Duffy allows a story to emerge from a set of circumstances rather than predicate it upon a spectacular opening or obvious crime. The terrible accident on the highway begets the accusation against Kelly, which results in a physical assault against him; circumstances which complicate the personal and professional lives of Paul and Bella. For Bella’s part, she must not only navigate the seemingly inevitable end to her career if she makes a stand against the pressure to name Kelly, but also the complexity of remaining friends with Paul as his relationship with her daughter teeters and threatens to collapse. Paul must deal with the potential for violence against Kelly in response to reports of Liam’s abuse, as well as an obvious but elusive suspect for Kelly’s own assault. Then there are the dark undertones of Kelly’s case which seem mired in what has unfortunately become a cliché – the physical abuse of children by priests – but may belie something even darker. The obvious crime is not always the story. Beneath the narrative surface lies secrets, like the underbelly of a beast.

Since the seemingly-omniscient detectives of the Golden Age of Crime, we have become used to more fallible, even somewhat broken detectives like Sam Spade, Cormoran Strike or Rebus. Their humanity serves to ground them in a more believable reality for the reader; to draw the narrative away from the stylised puzzle-narratives associated with the Golden Age and Cosy detective fiction. Duffy’s novel has all the hallmarks of traditional crime fiction, but it has a tone and purpose of its own. It is modern, it is a thriller, but it progresses at a pace more in keeping with the character of its setting. Like many modern crime novels, it is more Sam Spade than Miss Marple, but that doesn’t really capture the essence of the book at all. Ruel is closer to Todorov’s “vulnerable detective” than Poirot, but Duffy mostly avoids the salacious and thrilling cliché in favour of the thoughtful and inner worlds of his protagonists.

But Duffy has taken the idea of the vulnerable detective and expanded it beyond the context of a setting and its attendant dangers, to make his world, itself, a character within his novels. Like the crimes that Paul investigates – their purpose and origins sometimes initially unclear – the Mountains setting remains mysterious and imbued with potential danger. We are aware of nature on the doorstep of civilisation, barely restrained. Bella writes of Katoomba’s persistent fog, “It builds in the huge valleys until they can no longer contain it, then rises to enclose our towns, to look for points of entry into our homes and hearts.” The landscape is both separate and within: both an alien presence in the lives of its inhabitants, and a representation of the dark underbelly of civilisation, itself; of repressed natures which sometimes rise to the light.

In the first two novels this was primarily achieved through landscape and the communities of the Blue Mountains as mis en scene: an emphasis on the meaning of place and the relationship between place and culture. However, Duffy’s perspective seems slightly re-aligned in this third novel. The emphasis shifts to Paul’s deepening relationship with his adopted environment: “Some sort of offer was being made by the country, surprisingly welcome, although its terms were still indistinct.” This awakening sense within Paul is attributed to the landscape and enormous valleys beneath the towns, their canyons described poetically as “oceans of air”. Katoomba’s mist and fog, the landscape and its alien natural fringes, along with its associated ancient culture, remain foreign to many Western inhabitants of the Mountains. “They were in the Mountains, but not quite of them”. But when Paul takes up rock climbing with a local park ranger, Nicci Connors, he is introduced to an experience of the landscape and an understanding of it formerly unknown to him. Naturally, Nicci has a degree, but some of her talk borders on the mystical: “The valley is a creature, Paul, like the whole Mountains,” she tells him. Nicci maintains an emotional fidelity with the landscape, describing the act of climbing the cliffs as “a kind of love” which “brings us [herself and nature] closer.” Paul doesn’t fully understand this connection, but he realises there is an opportunity for growth and change:

. . . surely this landscape required a different kind of person. Maybe Nicci was normal here, adapted to the Mountains, in ways he could not yet fully understand. For a moment he felt the weight of his own ignorance, and wanted simply to escape, to move out from beneath it. But there was something on offer here, a transformation; he must be strong.

This potential for change is presumably available to anyone who can perceive its possibility. But the quotidian realities of life make actualisation difficult. Sib doesn’t see she is being exploited in her new job and in turn is neglecting her relationship with Paul. Paul has a numinous insight into the possibilities of change but may only reach for it if he can, like Sib, understand his own desires. Bella is mired in the pressures of finance and the challenges to her professional ethics. And Alan Tarrant, father to Liam, builds an enormous and spectacularly accurate representation of the Mountain’s landscape and a model of the Zig-Zag railway, but his project is a distraction against his own inner-turmoil. “I realised,” observes Bella, “all this had been a strategy to keep himself away from other human beings and the violence he inflicted upon them.” Alan Tarrant’s connection to the landscape is limited to the minutiae of his own creation, rather than offering the possibility for transcendence. Men like the Tarrants are burdened by their past and their own natures.

Once again, like its predecessors, The Man in Black is a slow burner. It takes longer to really take off than The Strange Death of Paul Ruel, but the characters’ problems are real and compelling, and Duffy’s world is complex and its issues contemporary. Meanwhile, the tension mounts and the payoff is rewarding.

The Bella Greaves Series is only sold in bookstores in the Blue Mountains, or it can be purchased online from michaelduffy.com.au.

The Bella Greaves Series

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!