My mother was one of nine children. Of the nine there was only one boy and he was born with a caul on his face. A caul is a piece of membrane clinging to a baby’s head at birth. It’s a rare condition and tradition has it that a baby born with a caul will never drown. So, they’re considered a lucky thing. In David Copperfield we are told that David is born with a caul on his face. It is advertised for sale for fifteen guineas because sailors would buy them as superstitious protection. When I was young, the first time I read David Copperfield, my mother showed me my uncle’s caul which was wrapped and stored carefully in a draw at my grandmother’s house. Even in the 1950s, a hundred years after David Copperfield was published, there had been offers of money for it, I was told, when he was born.

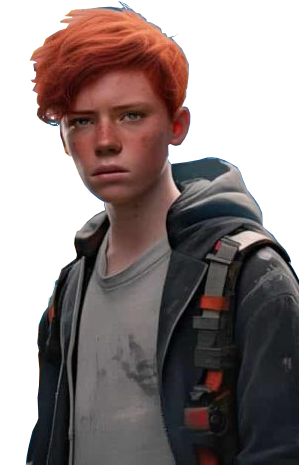

Demon Copperhead is a modern adaptation of Charles Dickens’ classic novel, and like David, Damon Field is born with a caul, although he is encased in the entire amniotic sac – a “baggie”. Born to a junkie mother, Demon cites his caul as a promise that he will he never drown, and that he “had a fighting chance”: that “the born of this world are marked from the get-out, win or lose” and his caul is the best assurance Damon has. Damon’s narrative therefore has a fatalistic promise; that no matter how bad things get for him, Damon will be all right in the end. As readers, we want to believe this because Damon is personable, intelligent, he is a talented drawer, he cares for others, and he represents a generation of people fighting the effects of opioid addiction in America. His mother dies of an overdose of OxyContin, and Damon, too, will become addicted to prescribed pain relief after a terrible sporting injury.

The plot of Damon Copperhead broadly follows the plot of David Copperfield and many of the characters in Kingsolver’s novel are adapted from Dickens’ work. Damon spends a lot of his early years growing up with the Peggot family, next door, and their son, Maggot. When his mother marries Murrell Stone (otherwise known as Stoner) Damon finds he is mistreated and beaten. When his mother dies from an overdose of OxyContin, Damon narrowly escapes becoming Stoner’s son. Stoner has lost interest in him and is already looking for his next girlfriend. Damon is institutionalised, living in a number of foster homes as he grows up. Mr Crickson prioritises the harvesting of his tobacco crop by boys under his care over their education. Damon also spends months working on a garbage site for Mr Golly, only to realise, “I was working for a meth lab.” Eventually, like Dickens’ protagonist, Damon runs away in an effort to take control of his life. The new life provided by his grandmother under the care of Coach Winfield would seem to be the opportunity Damon needs. The coach trains him to be an outstanding football player in a region where football players are community heroes. Damon seems to be on a straight path to success until he suffers an injury and succumbs to a life of addiction to prescribed opioids.

Readers familiar with Dickens’ original novel may identify some broad similarities with this basic summary, and for those reading Kingsolver’s novel for themselves, you can play spot the parallels as you read; how Kingsolver has adapted the story and its characters, as well as what she leaves out or changes. If you are interested in identifying characters and parallels in the story, I have made a short study of it which you can read by clicking here, rather than have me labour through too many comparisons in the middle of this review. Naturally, the comparisons I make are only the most obvious and necessarily limited. Cleverer readers will spot many more, no doubt.

For those unfamiliar with Dickens’ novel, do not worry. There is no need for you to read David Copperfield before reading this book. If you have read it, the story is an interesting echo behind Kingsolver’s narrative. But Damon has an entirely individual voice with a colourful turn of phrase, which is a strong feature of this novel, and a story that is his own. Kingsolver intends more than just a rewrite of Dickens. In an interview conducted with Liz McCormick for wvpublic.org, Kingsolver spoke of her inspirations for the novel:

I live in deep, deep southwest Virginia, which is the epicenter of the opioid epidemic. So we are living with this, and I wanted for several years to write about it, and I couldn’t think of a good way in that would make this story interesting and appealing to people, to readers, because it’s a hard subject. It’s dark, it’s difficult. Kids coming up in this environment. And then I sort of had a conversation with Charles Dickens, and I realized the way to tell the story is the way he told David Copperfield. Let the child tell the story.

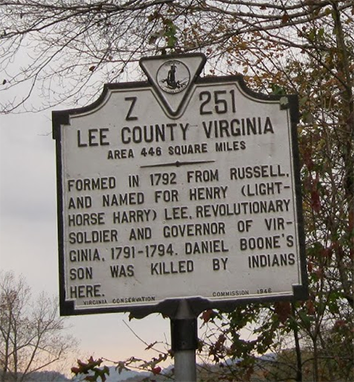

Damon grows up in Southern Appalachia, Lee County, Virginia. The northernmost tip of Virginia is nestled just south of Washington DC, but Lee County lies in the most western region of the state, on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains which form a physical barrier from the sea, hundreds of kilometres to the east. Damon longs to see the ocean from an early age, but the Appalachian Mountains and distance thwart his desires, a kind of metaphor for Damon’s struggle to achieve his aspirations as he grows. Geographically, Lee County has more in common with areas of West Virginia. Damon tells us his single-wide mobile home is situated in “Lee Country, between Ruelynn coal camp and a settlement people call Right Poor …” Lee County is broadly agrarian and mining country, populated by the working class and poor. People growing up in the region, like Damon, often suffer abuse or mockery for being ‘country folk’. Pejorative terms like ‘hillbillies’ and ‘red necks’ define them as unsophisticated, even backward. For a more personal and comprehensive discussion of the setting in relation to Kingsolver’s novel I suggest you visit Elizabeth Barlow Rogers website. Rogers is a resident of the region and offers a personal response to the setting of the novel.

Kingsolver’s decision to write about the opioid epidemic in America by appropriating the story of a nineteenth century English novel may seem counterintuitive, but it proves to be a clever strategy and it works impressively. I’m not saying that I enjoyed Demon Copperhead more than I enjoyed Dickens’ original. That was never going to happen, given that David Coperfield is one of my favourite books. And sometimes the modern adaptation is jarring if you know David Copperfield well. For instance, Kingsolver’s portrayal of the Micawber character, Mr McCobb, is jarring. Mr Micawber is a beloved character in David Copperfield, despite his hapless finances and dodgy schemes. Kingsolver’s McCobb, however, is mean-minded and grasping. He has lost the innocence and moral steadfastness that make Micawber so wonderful. But this is a minor reflection upon a book that turns out to be well written and possesses a strong sense of its own purpose. When I first picked up the novel it was with some degree of trepidation that I began to read it when I discovered that Kingsolver had written her novel with exactly the same number of chapters – sixty-four – as Dickens used for David Copperfield. I expected a chapter by chapter retelling of Dickens’ story in an American vernacular. This kind of thing has been done somewhat too often in American films and television: an almost direct translation of a foreign work for an American audience. The English Broadchurch, which starred David Tennant in both the original and the American remake, for instance: or the American Office, which paralleled the English original so closely in the first episode – virtually the same script – but which failed to be funny at all (it got better, I am told); or the remake of the Swedish The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo with Daniel Craig in the lead American role. There are many examples. But Kingsolver gives the years of Damon’s growing up a greater weight (in terms of the structure of the novel) than Dickens. When David marries Dora Spenlow he is an adult, but when Damon has a relationship with Dori he is still a teenager. He has to divide his time between her place and Coach Winfield’s to maintain the fiction that the coach is still his guardian. For Dickens, David Copperfield was a surrogate for his own life story, growing up in poverty but later becoming a famous novelist. But Damon represents a broad class of people whose stories are given context within a wider history of exploitation and prejudice, and so it is fitting that his story is predominantly of the period in his life when he is poor and vulnerable. In this sense, Damon is both Dickensian and modern.

But for Damon’s story to have any appeal, it is important that he is not a hopeless fool with nothing better to do than ruin his own life. Dickens contextualised his poor orphans within a system of workhouses, debtors’ prisons, poor living conditions and exploitative social and employment practices. Kingsolver contextualises Damon’s story within the broader milieu of racial and class exploitation and denigration, a byproduct of an economic system which denigrates the very people it has failed. As Damon matures, he is taught the history of his area and grows to understand how race and his social class are weaponised against his people.

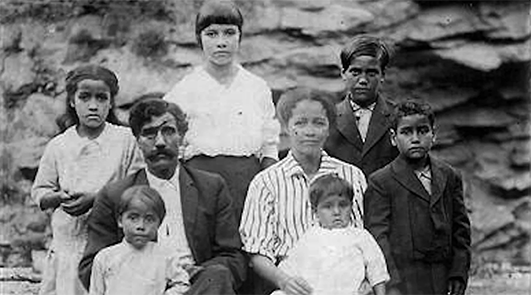

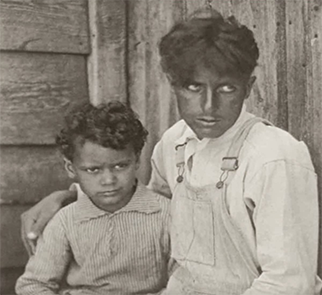

When Damon’s mother falls pregnant to Stoner, he wants her to have an abortion, concerned that the child will be “mulatto”. Damon points out that it was his father who was Melungeon, a mixed race of people common in the Appalachian region where they live. Some Melungeon’s are dark-skinned while others pass as white. There are even red-headed Melungeons like Damon. As Damon begins to find his way as a successful illustrator, he will use his skills to give voice to people of a Melungeon heritage. Mr Armstrong, a black teacher who encourages Damon to look into his family background for a class project, also faces racial prejudice, especially since he is married to Ms Annie, a white woman. U-Haul’s mother, Mrs Pyles, wonders, “What made him think he deserved that beautiful woman for his wife They’s a world a people a-wondering on that. Why she’d stoop to lowerin’ herself thataway.” Ms Annie suffers accusations of infidelity as a result of prejudice against their marriage.

But Kingsolver’s purpose isn’t to call out racial prejudice, per se. Instead, prejudice is contextualised within a wider framework of class exploitation. Black Americans are not common in Lee County anymore, since they were once cheap labour for the coal industry. There was little left for them once the coal petered out and they faced laws and customs antipathetic to them. Before, when the mining companies were moving into Lee County, the true value of the land was hidden from those who sold it. Then the mining companies created conditions which made the local population dependant on mining, alone: “Nobody needed to get all that educated for being a miner, so they let the schools go to rot.” Now, when children in the area are looking to leave school, it is “the army recruiters in shiny gold buttons come to harvest their jackpot of hopeless futures.” Being poor and white sometimes attracts similar prejudices suffered by black people. The reality of human nature is that “People want somebody to kick around”. For poor white people, the only option is to kick down again, and so the black community is ‘kicked’ by poor whites, too. Damon understands. “We’re the dog of America” he tells the innocent Tommy Waddles, and the broader American culture reflects an antipathy to people so easy to kick. Their humiliation is encoded in the language of prejudice – “rednecks”, “trailer trash”: through jokes – “I dated a Kentucky girl once, but she was always lying through her tooth”; and even in film: “Hunter’s Blood, Lunch Meat, Redneck Zombies”. Also, that scene in Deliverance.

This is the situation Damon faces as an orphan with mixed racial heritage in an area where even the white people are characterised as hopeless. In newspapers the area is portrayed as a “smudge on the map” and its people a “Blight on the Nation”. When they are called ‘hillbillies’ and ‘red necks’, they may either accept the humiliation and denigration, as is intended, or wear these appellations as badges of honour:

The world is not at all short on this type of thing, it turns out. All down the years, words have been flung like pieces of shit, only to get stuck on a truck bumper with up-yours pride. Rednecks, moonshiners, ridge runners, hicks, Deplorables.

It is a small nod to the problems that have seeded Trump’s America in working class regions: poorer people who feel abandoned by an economy and denigrated nationally. I am no Trump supporter, but it is important to find empathy where possible and Kingsolver’s narrative offers some insight into that. The danger of triumphal superiority lies in entrenching opinions which exacerbate problems.

This thought is borne by the dichotomies of city and country in the novel. Aunt June lives in an apartment block full of strangers which Damon finds alienating. There is no cohesive community that Damon understands and in the city being poor means living on the streets. He also understands through Mr Armstrong that city interests can be antipathetic to country society: the exploitation of mining companies, for instance. But the dichotomy conflates economic concerns with identity, too. Those pejorative slurs against country people also represent a different American mindset: about different notions of wealth and nation. It is the difference between a capitalist moneyed economy and more traditional forms of economy based on land, nature and interpersonal connections: growing and hunting food and bartering. In the city the poor have few options. They have no gardens, and without the ability to hunt food they shoot liquor store cashiers, instead, Damon is told.

Pharmaceutical companies are a part of the capitalist system which has exploited the poor. On a personal level, they are represented by Aunt June’s short-term boyfriend, Kent, who is encouraged to promote drugs to doctors through a reward system that includes greater personal benefits, even overseas holidays. Aunt June characterises this practise in the language of mining – of “prospecting” – to suggest that this is an ongoing exploitation of poor communities which has historical antecedents:

Coming here prospecting. She said Purdue looked at data and everything with their computers, and hand-picked targets like Lee County that were gold mines. They actually looked up which doctors had the most pain patients on disability, and sent out their drug reps for the full offensive.

In Kingsolver’s story the drug problem facing many American communities is not merely a personal failing or an issue of specific to poorer classes, but the result of systemic exploitation which relies upon the demonisation of its victims.

But Demon Copperhead is not just an issues book. Like its predecessor, its characters come to life and their problems are real. Fast Forward, who is adapted from Dickens’ Steerforth, is just as charismatic and uncaring, and Emma just as tragic. We see not only Damon falling into a whole cycle of poverty and addiction, but other minor characters facing problems, too, like the Department of Social Services (DSS) worker, Miss Barks, who studies at night to qualify for a teaching job that Damon knows will improve her economic circumstances only marginally. Aunt June, who has no clear correlation with any of Dickens’ characters, but who might be likened to the caring Mrs Peggotty, is the real hero of this story. As a straight shooting, clear-minded medical practitioner, she works not only to save characters like Emmy and Damon from their addictions, but she resists the efforts of corporations to exploit her community. But her resistance is not just a trope. Her connection to Emmy – she adopts her – and her determined rescue of her from a drug house (thereby undertaking the role of Mr Peggoty from David Copperfield) instils a greater human dimension to a character who might otherwise have felt emotionally removed for the reader from the issues she champions.

Towards the end of David Copperfield David describes a scene in which a ship founders against rocks near the shore during a violent storm. Several men are washed to their deaths as they try to cut a broken mast away from the ship. Dickens was one of the most brilliant writers when it came to dramatic scenes like this. Ham, who has been slighted by Emily when she elopes with Steerforth, ties a rope about himself to try to press through the waves to help the people on the ship. David, who watches from the beach, sees both Ham and his rival, Steerforth, who had been on the ship, washed ashore, drowned.

Damon, who watches the equivalent scene in Demon Copperhead, is later tormented by the thought that it should have been him who took the risks taken by Hammer. After all, he was the one born with a caul. He was the one immune to drowning. Damon dreams of seeing the ocean throughout this book: “Still waiting to meet the one big thing I know is not going to swallow me alive.” By implication, everything else has the potential to drown Damon. Damon lives far from the ocean, but it is in Lee County that he almost drowns, not in water, but by means of a system that has abandoned young people like him: “Like every boy in Lee County I was raised to be a proud mule in a world that has scant use for mules.” Like David Copperfield’s story before him, Damon’s is one of climbing out of a hole that society has made for the poor. It is a story of falling into despair, but it is also a story of hope that avoids naivety and acknowledges institutional realities for people like Damon in rural America. This was an excellent book and I would recommend it, either read in conjunction with David Copperfield or on its own, just as you like.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!