Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible is initially set in 1959, the period just before the Republic of the Congo’s independence from Belgium in June 1960, and following that, the rapid breakdown of the republic due to foreign pressures. The book is not only an astute dramatization of that political period from the perspective of a Baptist missionary family, Nathan and Orleanna Price and their four daughters, Rachel (fifteen years old), twins Leah and Adah (fourteen), and Ruth May (five), living in the village of Kilanga, but is also a dramatic recount of the fracturing of the family and the challenges to their faith.

Nathan Price, although warned not to travel to the Congo, takes his wife and four daughters to live a new life in Africa, with ambitions of spreading God’s word and converting the local population to Christianity. Like other emissaries of colonial culture, his faith in Christianity makes him arrogant. He believes he has something to impart to Africans, but sees no value in the local culture. Until he achieves his purpose, Africa remains unformed, where only darkness moved on the face of the waters.

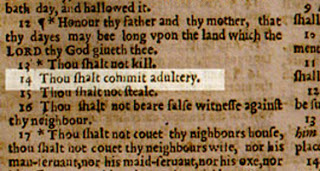

Ironically, it is Price’s conception of Africa as a blank slate that is the core of his failure. In his desire to baptise his potential followers he fails to understand the fear his intentions instil. Instead of celebrating redemption, the villagers fear baptism in the Congo where a young girl was eaten by a crocodile less than a year before. Does this preacher want to feed our children to the crocodiles? But for Nathan Price, God’s word is something monolithic, unchanging and unquestionable. In his first speech to the Congolese villagers he warns of the Lord’s wrath against the sinners of Gomorrah, heedless in their nakedness

, despite the bare-breasted women in his audience. He does not see, as his predecessor Brother Fowles did, that God’s word must be adapted to the circumstances and experiences of the Congolese people. Further, in attempting to bypass his translator, Anatole, in his desire to speak more directly to his flock, Price’s meaning is marred because of his ignorance of the subtleties of the Congolese language.

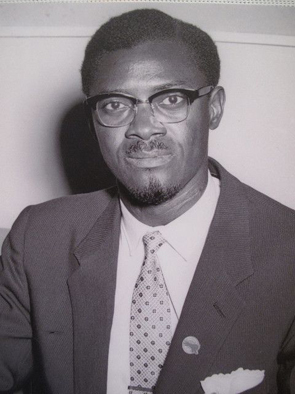

Despite his education and solid faith, Nathan Price never attains a true insight into the motivations that drive him, or the part he plays in the wider enculturation of African nations, undertaken by western nations like Belgium and America, to exploit the riches of Africa. The Congolese, existing at a historical nexus between traditional and western belief, between traditional ways and the imposed ideology of capitalism and democracy, must decide what kind of future they will embrace. Under the leadership of men like Patrice Lumumba, the Congo is moving toward independence under a democratic model, yet their future is uncertain. The Congo’s former colonial rulers are set to withdraw, leaving the new Republic of Congo with little infrastructure other than that which was needed by its former rulers to rip diamonds and other minerals from the earth and export them.

Central to the story is Nathan and Orleanna’s four girls who narrate from their initially limited perspectives. The novel is engaging and well written, although Kingsolver necessarily avoids a realistic narrative voice for the children. Ruth May at the age of five is far more sophisticated and articulate than her years would realistically permit, but Kingsolver allows her young characters moments of misapprehension and even some amusing malapropisms which serve to further not only characterisation, but also the thematic concerns of the novel. When her sister, Rachel, is promised as a bride to a village elder, Ruth May talks about female circumcision, a subject she has heard her parents discuss but clearly does not understand; all she knows is that it shocks and angers her parents. With typical childish naivety, she explains that Rachel would have to have the circus mission

. Even Rachel, the eldest daughter, misunderstands her father’s Biblical teaching when she hears the story of Moses tromping down off Mount Syanide with ten fresh ways to wreck your life.

Later we learn that the villagers have little more to eat than Manioc, a tuber which has the nutritional value of brown paper bag, with the added bonus of trace elements of cyanide.

The homophone links the diet of questionable nutritional value and religion.

However, it is not Kingsolver’s task to undermine religion, per se, even though each of the women, Orleanna and her daughters, have their faith challenged by the extremes of Nathan – his violence and his unwavering devotion to his mission – and the Congo. Kingsolver foregrounds language throughout the novel as part of the deconstruction of western ideologies that support the foundations of colonialism. Kingsolver portrays ideologies such as capitalism, democracy and socialism as static constructs, while Africa – its nature, its people and their language – have a natural fluidity not comfortably contained by rigid ideological systems. Democracy, usually touted as a political jewel in western culture, becomes a divisive instrument in village life. The Congolese, who work through negotiation to achieve a consensus in village decisions, find democracy confronting, with its notion that the wishes of almost half of those with an interest in an issue can have their concerns and opinions swept aside by a vote in a winners-take-all situation. Tata Nda, a village leader, demonstrates the destructive power of democracy when he turns it against Nathan Price in his own church to stage a vote against the influence of Christianity in the village.

Nathan’s own attempts to communicate directly with the Congolese villagers are also undermined by the slipperiness of the Congolese language. To an outsider, the subtleties that form the language are not apparent. Words that might mean one thing in one context or with one vocal inflection take on entirely different meanings with others. The situation is demonstrated practically, with Nathan’s attempts to cultivate a garden and his attempts to sermonise. He does not realise that a plant he is attempting to work with is poisonwood. It gives him a rash against his skin. Likewise, Orleanna almost stokes a fire with poisonwood branches which would have killed her family. Yet the Congolese name for the poisonwood tree, ‘bängala’, also means something precious and dear

, so Nathan Price likes to declare in his sermons, Tata Jesus is bangala!

, which translates in the villagers’ minds as Jesus will make you itch like nobody’s business!

The issue of language is central to the novel, because at its heart the autonomy of a people resides in representations they make on their own behalf. Connected to this idea is the perceptions of Adah, who is sympathetic with the issues of the Congolese and who eventually marries Anatole, her father’s former interpreter and a political activist. At first, Adah is obsessed with the notion of backward speech as a child. This arises from her hemiplegic condition – seemingly paralysed on one side – which she believes affects the way one side of her brain is forced to interpret words, both backward and forward. As a result, Adah is preoccupied with palindromes which have a subversive tincture, with their frequent themes of ‘evil / live’ (Evil, all its sin is still alive!

) and forbidden words like ‘damn’ worked into the sentences she creates. Added to this, Adah is aware of the vagaries of language representing the disjunction between western ideologies and the realities of the Congolese: Many Kikongo words resemble English words backward and have antithetical meanings: Syebo is a horrible, destructive rain, that just exactly does not do what it says backward.

Adah’s way of thinking gives her insight into the potential damage of colonial intrusions like the Christian doctrine. Her mind turns the coloniser’s doctrines against themselves. If African children can be sent to hell for being born too far from a Baptist church, might not American babies also be sent for being born too far from the jungle or having not tasted palm nuts, like a sacrament? When she learns that the American President Eisenhower want Patrice Lumumba, the Republic of Congo’s new Prime Minister, dead, she wonders whether it might be as justifiable for Eisenhower to be killed with a poison arrow.

Language, doctrine and ideology, not guns and armies, are the primary weapons of the coloniser. The representation made of a nation and of that nation’s relationship with dominant ideologies through language is critical. Christianity, like democracy and capitalism, are centrist concepts that reside within the purview of Western nations, shaping and characterising the Republic of Congo, later to become Zaire, and its relationship with its colonisers. Kingsolver tellingly uses the language of marriage to foreground the exploitative relationship between coloniser and colonised. Of her own marriage, Orleanna says she encountered my own spirit less and less […] Nathan was in full possession of the country once known a Orleanna Wharton.

With reference to Joseph Conrad’s novel about the exploitation of the Congo, Orleanna states, I was lodged in the heart of darkness, so thoroughly bent to the shape of marriage I could hardly see any other way to stand.

Orleanna pictures herself Like the Congo, barefoot bride of men who took her jewels and promised the kingdom.

Orleanna links the idea of marriage with dominance and exploitation. It is no accident that the exploitation of Africa’s mineral wealth is characterised as an exploitative marriage, describing profiteers leaving Africa with its wealth, as a husband quits a wife, leaving her with her naked body curled around the emptied-out mine of her womb.

Later, as Zaire falls into corruption due to the exploitation of President Mobutu and America, Anatole tells Adah:

Like a princess in a story, Congo was born too rich for her own good, and attracted attention far and wide from men who desire to rob her blind. The United States has now become the husband of Zaire’s economy, and not a very nice one.

Traditional economies are replaced by concepts of production, of trade, capitalism and the political systems that support them. The notion that food might be consumed at the place where it is gathered – the village – is ironically challenged by the notion of abundance, of specialisation and wealth that exist in the countries that exploit Africa.

What makes The Poisonwood Bible such a good book is that the Congo/Zaire’s struggle for independence is a compelling story told from a critical viewpoint sympathetic to western sensibilities. The struggle of Orleanna to escape her obsessive and domineering husband is also the story of Africa. The struggle of the Price women to come to terms with their own faith, with Africa and the country of their birth, America, is a journey that characterises the many facets of the problems of colonialism and what comes after it for the reader. It is a story not only about family and country, but about the struggle for identity and a search for one’s own inner morality. Kingsolver’s narrative works on many levels, all of which work in tandem. It’s a broad and satisfying novel with compelling characters and large themes. Highly recommended.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!