In Book 19 Achilles and Agamemnon reconcile and Achilles arms for battle.

As dawn breaks Thetis returns to the shores of Troy with Achilles’ new armour. She finds him weeping over the body of Patroclus. She urges Achilles to leave Patroclus and accept his new armour. The armour, wrought by a god, is so beautiful and bright that Achilles’ men fear to look directly upon it. Achilles agrees he must arm for battle but he is concerned for Patroclus’ body. Thetis assures him that she will protect the body from flies and preserve it from decay. She breaths ambrosia and nectar into Patroclus’ body to preserve it.

Achilles heads out to rouse the Achaean soldiers. They begin to gather, even wounded men like Diomedes and Odysseus. Agamemnon comes in last, also wounded. Achilles calls for an end to the feud between him and Agamemnon. He says that only the Trojans have benefitted from it. Achilles is eager to return to battle and urges the troops to prepare immediately. Agamemnon stands to reply. He speaks of the criticism he has often received over the feud, but says he is not to blame. Rather, it is Zeus’ fault: that he was influenced by Zeus to act as he did, and that Zeus’ daughter, Ruin, blinded him to the consequences. To illustrate his point, he tells the story of how Zeus, himself, was blinded by Ruin when Hera tricked Zeus into empowering Eurystheus, son of Sthenelus, at birth, rather than Heracles, as Zeus had intended. For this trick Zeus had flung Ruin from the heights of Olympus. The point of Agamemnon’s story is that if a god could act against his own will in these circumstances, what hope had he? Agamemnon is eager to end the feud and offers Achilles gifts. He urges Achilles to wait while his aides fetch the gifts to display before him. But Achilles is not really interested in gifts. All he wants to do is get back to the fight immediately.

Odysseus speaks next. He says it is not wise to send the men back into battle straight away. They are hungry and they will fight better when they have had food and rest. He thinks it a good idea for Achilles to wait and to view the gifts that Agamemnon is offering. He also says Achilles should hear Agamemnon swear an oath that he has never slept with Briseis. Finally, he says that allowing Agamemnon to present Achilles with a feast will be a suitable peace offering.

Agamemnon responds by promising to swear the oath that Odysseus has proposed. He asks Odysseus to find young men to haul the gifts from his ship to display to Achilles, and commands Talthybius to prepare a boar for sacrifice to Zeus. But Achilles cannot abide delay. He says it is inappropriate to feast while the bodies of their men lay slaughtered in the field by Hector’s army, which was aided by Zeus. He proposes to battle immediately and then feast when the sun goes down. He says he will neither eat nor drink until the sun has set. Instead, he wants slaughter. Nevertheless, Odysseus continues to press for delay. He says the men cannot fight well if hungry and there will be even more dead, otherwise. When they have eaten, they will fight more fiercely. Several young men are sent to Agamemnon’s tent and they return with seven tripods, a dozen stallions, eight women, including Briseis, ten bars of gold and other gifts for Achilles. Talthybius presents Agamemnon with the boar and he cuts hair from its head to begin his rite. Agamemnon swears to the gods that he never slept with Briseis, nor did any other man while she was in his tent. He then sacrifices the boar to Zeus. Achilles completes the ritual by blaming Zeus for the influence he exerted over Agamemnon that caused the feud and demands the god take the boar as an offering, so that they might return to war.

The Myrmidons take the gifts back to Achilles tent where Briseis weeps over the body of Patroclus. She remembers his kindness; how he comforted her when Achilles killed her husband, and how he vowed to make her Achilles’ wife, which would have elevated her above the status of a slave.

The warlords now beg Achilles to eat, but he insists on fasting until the sun goes down. He grieves, still, for Patroclus. He thinks of his own father who would likely be wondering about his own fate, and characterises his own love of Patroclus as that of a father to a son. This thought takes him to thoughts of his real son, Neoptolemus (also known as Pyrrhus) whom Achilles had hoped Patroclus would take care of when he had died. His thoughts next return to his own father, waiting to hear news of his own death.

Zeus witnesses Achilles grief while the rest of the army takes its meal. He asks Athena to go to Achilles and give him nectar and ambrosia to sustain him against hunger. She does this.

The troops begin to move out, impressive in their armour. Achilles now arms for battle, too, putting on his new armour and hoisting his shield. The gleam of the shield is so bright that the light of it blazes into the sky. Achilles tests the fit of his armour, which is perfect, and then takes up his father’s spear, which is too heavy for any other fighter to wield properly.

Automedon readies Achilles’ chariot. He harnesses Roan Beauty and Charger to the chariot. Achilles chastises the horses, telling them to try harder this time and to bring their charioteer back home alive. Hera gives the horse, Roan Beauty, the ability to reply. The horse says they will save Achilles’ life but there is no preventing Achilles’ imminent death. He says that the horse team was not to blame for Patroclus’ death but Apollo, and so too will Achilles die by the will of a god.

Achilles, is angry at this prophesying by his horse. He says he knows he will die, and he drives his team out for battle.

In this book Agamemnon, anxious to have Achilles and his Myrmidons back in the fight, is willing to offer just about anything, including Briseis, as part of a larger compensation to appease Achilles. But after the death of Patroclus, it is evident that Achilles’ towering grief has made the feud over Briseis irrelevant. How do we know this? Achilles can barely tolerate any waste of time, including waiting for the presentation of the gifts:

Achilles’ change of priority should be read against the arguments made in Book 9, when Phoenix, Ajax and Odysseus visit Achilles’ tent to offer the return of Briseis with other gifts in compensation. At that point Achilles was struggling with the two fates allotted him, to either live long and die obscure, or have a short and glorious life (See my discussion titled “A Quantitative versus a Qualitative Choice” under ‘Characters and Legends’ for Book 9). Achilles rejected Agamemnon’s offer at that point because he felt that honour had already been taken from him, and so it was senseless to risk his life. Now, what is essentially the same offer is of little interest for Achilles. He will return to battle, regardless, to avenge Patroclus.

For his part, Agamemnon’s argument for reconciliation with Achilles has been based upon the following:

Even so, Achilles chooses to respond to Agamemnon’s sacrifice of the boar and the oath he swears to the gods. Agamemnon’s oath is to assure Achilles that he has not slept with Briseis, but Achilles’ response makes no mention of this: he does not care. Instead, his response is to accuse Zeus on Agamemnon’s behalf. He disrespectfully commands the god, “Go now, take your meal” – a reference to the sacrificed boar. In this manner, Achilles uses the god to side with Agamemnon so that the battle can be joined as soon as possible.

The story Agamemnon tells about how Hera and Ruin tricked Zeus is 57 lines long in Fagles’ translation. Given that book 19 is one of the shortest books of The Iliad – 503 lines – this means that this digression comprises over a tenth of the entire book. Given that it is this story that helps to sell Agamemnon’s reconciliation with Achilles, rather than the return of Briseis, it is worth considering in greater detail.

The basics of the story, as they appear in The Iliad are as follows:

‘Heracles Kills the Nemean Lion’, c.560-540 BCE

‘Heracles Fighting the Hydra of Lerna’, c.525 BCE

‘Heracles and the Stymphalian Birds’, 6th Century BCE

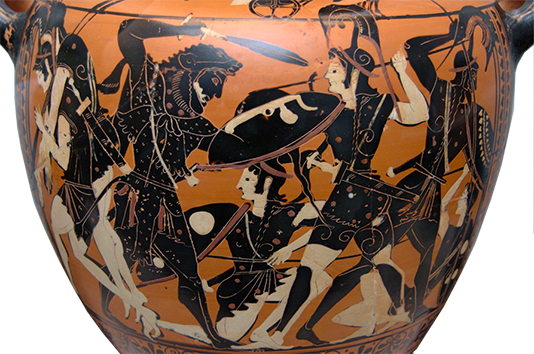

‘Heracles Battling the Amazons’, c.530 BCE

‘Heracles, Cerberus and Eurystheus’, c.525 BCE

Hera’s motivation for this lay with Zeus’ relationship with Alcmena. Zeus had disguised himself as her husband while he was away and got her pregnant with Heracles. She was also pregnant with Iphicles, who was the son of Alcmena’s husband, Amphitryon, not Zeus.

But there is more to the story. To start with, Fagles’ translation states that Hera, “stopped Alcmena’s hour of birth, held back the Lady of Labor’s birthing pangs”. But she did more than this. She sent Eileithyia, her daughter, who was the goddess of childbirth, to sit outside Alcmena’s bedchamber with her legs crossed, so that Alcmena could not open her own legs and give birth. Hera intended that Heracles would be still-born. But Eileithyia was tricked into standing and thus uncrossing her legs, and so Heracles was born. There is also the story of the snakes killed by Heracles when he was only a child. These were sent by Hera to kill Heracles but Heracles demonstrated his future potential by killing them, instead. But the most famous consequences of Zeus’ infidelity and Hera’s outrage were yet to come.

Later, after Heracles had become famous for many feats and had married and had children, Hera again moved against him. She sent him momentarily mad. He believed he saw two demons in his home and a great dragon. He killed them all. After, Hera allowed Heracles to see the truth. He had, in fact, murdered his wife and children. In grief, and in order that he might expiate his crime so he might see his family in the afterlife, Heracles sought the advice of the Delphic Oracle. He was told that for ten years he must undertake any task he was told to do without question. He was advised to go to King Eurystheus in Argolis to undergo his punishment.

And this brings the story full circle to Eurystheus who was, by this time, king of Tiryns. Heracles presented himself to the king, Heracles’ cousin, who was aware of Heracles’ reputation as a Greek hero. Heracles was well aware that Eurystheus was a lesser man than he, but he had to swallow his pride. Eurystheus declared that Heracles would perform ten tasks over ten years to pay for his crime, which are now known to us as the ‘labours of Heracles’. Most of the tasks involved killing mythical creatures like the Nemean Lion, the Lernaean Hydra and the Erymanthian Boar, or capturing creatures like the fleet-footed Ceryneian Hind or the Cretan Bull (the father of the Minotaur), or driving off creatures like the man-eating Stymphalian birds or stealing the man-eating Mares of Diomedes. Other tasks required retrieving objects, like the Belt of the Amazonian Queen, Hipolyta, a task which potentially placed Heracles in conflict with the Amazons: or retrieving the Golden apples of the Hesperides, which almost saw him trapped holding up the world in Atlas’ place. He was also made to perform tasks, like cleaning out the stables of King Augeas, which had not been cleaned in decades. Heracles diverted two rivers to clean them out.

Ultimately, Heracles performed twelve, not ten labours, since Eurystheus claimed that the cleaning of the stables did not count and the killing of the hydra had been achieved with help. Eurystheus agreed to release Heracles from any further tasks when Heracles brought Cerberus, the three-headed guard dog from the Underworld.

Agamemnon’s allusion to the story of Heracles’ and Eurystheus’ births is made to give his own denial of responsibility for the feud between him and Achilles some credibility: at least some face-saving means to end it. The story highlights Hera’s vindictive desire for revenge and the fact that even Zeus, himself, stands helpless against the wiles of Hera and Ruin. The consequences of Hera’s meddling suggests the profound impact the actions of the gods can have on the lives of men. Heracles’ family are killed and he spends years trying to atone for it. Likewise, Agamemnon suggests that the feud and its dire consequences are to be attributed to the gods, alone.

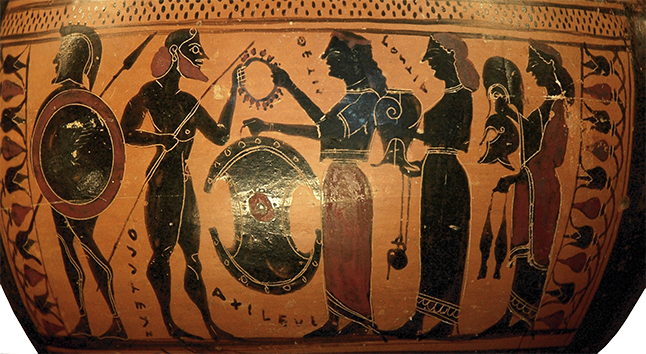

This sixth century black figure hydria portrays Thetis presenting Achilles with his new armour, made by Hephaestus the night before. Thetis has convinced Achilles to wait until his shield and new armour are forged, rather than rushing directly into battle to seek his revenge. Perhaps it is the fact that he has already waited longer than he can bear that explain his impatience with Agamemnon and the gifts her presents, as well as Odysseus’ advice that he should wait until the soldiers are fed and rested.

This image represents this important moment in the story, with Thetis aided by women who each bear a part of the armour. Greek pottery painters of this period considered themselves artisan, not artists, which may explain the representation of plot here without an attempt to capture the emotional significance of the moment. The following two paintings by Benjamin West attempt to capture the emotional weight of this moment in the story.

.png)

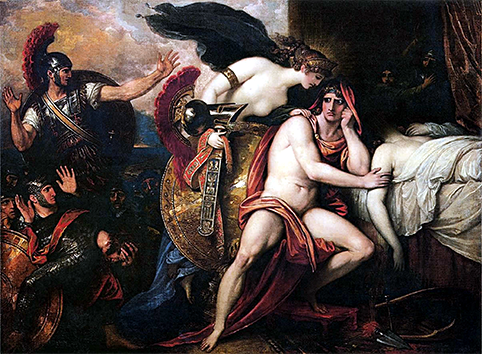

Benjamin West painted six versions of the scene of Thetis presenting Achilles with his armour, of which five now remain. Setting aside the strange habit of neoclassical art to present its figures naked, this painting is strange, to me, in its interpretation of the scene as well. Achilles’ hand is raised, seemingly to ward off his mother, as though he does not wish her to interrupt him in his grieving for his friend, Patroclus, who lies dead beneath him. The expression on Achilles’ face looks hostile, even though Homer’s story would suggest he should have been waiting anxiously for his mother’s return. The armour appears weighty, since Thetis has cast it at Achilles feet, except for the helmet. She appears to almost hover above Achilles, which suggests her divine nature. The helmet she presents Achilles is held close to his face, as though it is a mirror or a version of himself, he has forgotten. The presentation of the helmet and the reception given by Achilles does not capture the sense that he is already resolved to fight again.

This is another of the five versions of this scene painted by Benjamin West that still exist. This version is interesting not only for the composition of the figures, but also for the elements it has added to the scene. First, Thetis tries to engage Achilles personally rather than force the helmet upon him. Achilles, instead of looking aggressive, now looks like he is in grief or grumpy. His body, leaned in towards Patroclus’ corpse, shows him still steeped in grief, which again suggests he has not yet reached a resolution to fight. In this version West has added the figures of other soldiers who look upon the scene in anticipation. Their raised hands and arms are meant to be dramatic and suggest the import of this moment, but they may also appear comical to some who view this image.

In this painting Peter Paul Rubens’ baroque style achieves a scene that is reminiscent of a stage. This is particularly suggested by the architectural features that border the painting. In the background lies Patroclus’ body, mourned by two women. But in the foreground is a scene that is celebratory. Nestor presents Briseis to Achilles, and Achilles seems to be running or lunging towards her, as though to reignite a passion. Between them Agamemnon stands with a finger raised to the sky, perhaps alluding to the gods whom he heavily references in this book of The Iliad. Two men place gifts before Achilles and other gifts, including horses and women, are arrayed behind Briseis. While the elements of the painting are essentially correct, I think the painting fails to capture Achilles’ psychological state. In The Iliad, Achilles can think of nothing except to return to battle so that he might avenge Patroclus. Patroclus is not in the background but the foreground of his thoughts. Achilles’ attitude to Agamemnon’s gifts, including Briseis, appears dismissive. The gifts which Agamemnon may have once used to appease Achilles no longer have any bearing on his desire for revenge, which overrides Agamemnon’s insult. This is a wonderful painting, but it emphasises, to my mind, a romantic reunion, which has more visual appeal, than the darker place inhabited by Achilles’ thoughts at this moment.

Achilles’ horses were Xanthus and Balius, although some translators, including Robert Fagles, translate Xanthus as ‘Roan Beauty’. Given that I am using his translation, that is the name I use in the summary. These two horses are meant to be immortal. Automedon, Achilles’ charioteer, is tasked with readying the horses and harnessing them to the chariot towards the end of this book. While this image does not portray any specific incident in the book other than that, it does suggest the power of the animals and Automedon’s relationship with them.

At the end of book 19 Hera gives Xanthus the power of speech. Xanthus uses this power to warn Achilles of his fate and to deny responsibility for Patroclus’ death.

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!