The title of this book is somewhat ironic. While the first section of the book tells of Agamemnon’s glorious heroism against the Trojan forces, Zeus waits to turn the tide once again. By the end of this book, the Argive forces are in bad shape and Nestor feels compelled to ask Patroclus to save the situation.

As dawn arises Zeus sends the goddess Strife into the Argive camp. Her high-pitched cry only inspires the Greek forces. Agamemnon calls his men to arms and dons his armour. His breastplate is a gift from Cinyas who was once a guest of his. It is inlaid with gold, enamel and beaten tin, as is his shield, to present an impressive figure. He is so impressive, Homer tells us, that the goddesses Hera and Athena are awestruck at the sight of him. Meanwhile, Agamemnon’s forces are well ordered and prepared. Zeus releases a shower of rain upon them to try to drive them to panic. Across the plain the Hector is also donning his armour and the Trojans ready themselves for battle.

The armies clash as Strife watches the combat. In Olympus the gods are angry at Zeus and the stormy clouds he has unleashed, but they refrain from directly crossing him. As the morning wears on the battle turns in the Greeks’ favour. Agamemnon is personally instrumental in this. He kills many fighters in a variety of ways, including Priam’s sons, Isus and Antiphus. Agamemnon’s attack is so fierce that Homer likens him to a lion. He also kills Pisander and Hippolochus when their frightened horses leave their chariot exposed. They beg for mercy but Agamemnon remembers that their father, Antimachus, proved treacherous during a Trojan council. He tried to have Menelaus killed when he was in Troy as an ambassador. So Agamemnon kills the two sons as revenge. As the battle rages Agamemnon urges his men to greater and greater slaughter, until many chariots are pulled through the battlefield, driverless.

Seeing this, Zeus draws Hector out of range of the Argive weapons. The Trojans make a general retreat, trying to reach the city walls where they stop to face their enemy in front of the Scaean Gate. Agamemnon and his forces follow, cutting down stragglers. At this point Zeus descends to a ridge on Mount Ida with lightening in his hands and instructs Iris to take a message to Hector. His message is that Hector should remain out of the fight until Agamemnon is wounded and retreats to his ships. At that point, Zeus says, the tide of battle will turn in Hector’s favour.

Hector rallies his troops. Agamemnon, now in position, attacks first. Iphidamas, who left his new bride to fight for the Trojans, attempts to kill Agamemnon, but his spear fails to pierce Agamemnon’s breastplate. Agamemnon kills him. Iphidamus’ brother, Coon, sees his brother killed. He attacks Agamemnon and manages to wound him on his forearm. He then attempts to retrieve his brother’s body, but Agamemnon cuts off his head before anyone can help him. Agamemnon continues to fight, but as his wound dries the pain becomes too unbearable and he takes a chariot back to the Greek ships.

With Agamemnon gone Hector heeds the advice of Zeus and calls to his army to inspire them. They renew the fight against the Argive forces, with Hector again in the forefront of the fighting. Like Agamemnon before him, Hector now racks up a list of Greek captains who fall to him in battle. Odysseus, who sees what is happening, appeals to Diomedes to help the Argive forces stand fast against the Trojans. They fight back and this helps renew their men’s spirits. They kill several Trojans, including Agastrophus. Hector, seeing their effect, marks them out and charges at them. Diomedes flings his spear at Hector but it is deflected by Hector’s helmet. Nevertheless, Hector is stunned and falls to his knee. A second spear from Diomedes falls near Hector and Hector flees, taunted by Diomedes. Paris, who sees this, aims his arrow at Diomedes and hits him in the foot, pinning him to the ground. Diomedes rails against Paris, suggesting that he couldn’t win in a fair fight and that he is a coward. Odysseus rushes in to protect Diomedes while he removes the arrow from his foot. Diomedes also jumps into a chariot to head back to the ships, leaving Odysseus on his own. Odysseus finds himself cut off from his forces, alone, facing numbers of Trojans. He is fearful but also mindful of the reputation he would acquire if he fled. So he stands his ground and fights fiercely, killing several Trojans. One of these Trojans, Charops, is the brother of Socus, who calls Odysseus out. He stabs through Odysseus’ shield and wounds him. Odysseus, enraged, swears to kill Socus, and Socus flees. But Odysseus sends a spear into his back, which emerges from his chest. Odysseus then removes the spear from his own wound and calls for help.

Menelaus hears Odysseus’ cry and asks Ajax to help him save Odysseus. They find Odysseus surrounded but Ajax lays into the Trojans and scatters them while Menelaus leads Odysseus away. Meanwhile, Homer describes Ajax as a wave that sweeps the Trojans aside. Hector, seeing what is happening, returns to try to take control, where Nestor and Idomeneus are in the thick of the fighting. But the situation changes when Machaon, the healer, is wounded. Idomenues calls to Nestor to get Machaon away from the battle, since he is valuable as a healer.

Cebriones warns Hector that he risks losing if he focuses on the fringe of the battle while their main force is still being routed in the centre. Hector heeds the warning. While Cebriones aims his chariot into the thick of the fighting, Hector avoids engaging Ajax and also returns to the main part of the battle. Meanwhile, although Ajax is fierce, he is outnumbered, and Homer likens him to a lion being forced back by many hounds. Even so, he still kills men as he makes a stubborn retreat.

Eurypylus, who sees Ajax’s plight, tries to help him. He kills an Apisaon captain with his spear but is himself wounded in the thigh by an arrow shot by Paris as he attempts to strip armour from the captain’s body. Eurypylus staggers back to his men and tells them to help Ajax. Ajax is rescued.

Achilles sees Nestor returning from the battle with the wounded healer, Machaon. He asks Patroclus to go to Nestor to confirm that it is Machaon who is wounded. Patroclus finds Nestor and Machaon drinking a brew served to them by Hecamede, a woman given to Nestor as a prize from the city of Tenedos. Having confirmed that the wounded man was indeed Machaon, Patroclus says he will return to Achilles. But Nestor asks him to stay. He expresses contempt for Achilles and his supposed concern. He asks, “How long will he wait?” Nestor laments his own age which limits his participation in the battle. He then recounts a story of his own glory days when he first went into battle.

Nestor was the last of twelve sons, the rest killed in conflicts against Heracles. The Epeans had taken advantage of this, harassing Pylos, the town of Nestor’s father. Nestor had been rustling the Epean herds in reprisal for the wrongs done to his people, and tells how he killed Itymoneus when he was challenged for stealing cattle. Itymoneus’ workers fled and Nestor was able to take a herd of fifty cattle and many sheep back to Pylos. He returned them to his people as reparation for the wrongs done by the Epeans. But the Epeans came three days later in large numbers. They razed a frontier fort. The Pylians raised an army but Neleus would not allow Nestor to fight. He said he was too young and inexperienced. He hid Nestor’s horses, but Nestor walked to the front lines. The Epeans closed around their fortress but the Pylian forces engaged in battle at dawn. Nestor says he was the first to kill a man and took his chariot. During the course of the battle, Nestor says he took fifty chariots. The Pylian army pursued the Epean army across the plain, killing many. Nestor says this is a story that shows how he entered the first ranks of men.

It becomes clear that Nestor’s story has been told either to inspire Patroclus, or to goad him into action. Nestor recalls when he met Achilles and Patroclus during the period they were recruiting forces for this current campaign. He recalls that Patroclus’ own father had urged him to always offer Achilles good advice, since he is actually the older of the two men. Nestor acknowledges that Achilles might listen to Patroclus, but it seems he is not willing to take that risk, now. Instead, he proposes a different course of action. He urges Patroclus to lead the Myrmidon army into battle dressed in Achilles’ armour. If the forces mistake Patroclus for Achilles, they will not only benefit from the fresh troops – the Argive forces are near spent – but the sight of Achilles on the battlefield will boost morale.

Patroclus is moved by Nestor’s story and his suggestion. When he leaves, instead of returning directly to Achilles, he walks near the rest of the Argive fleet where he meets the wounded Eurypylus. He is moved by the sight of Eurypylus’ wound and the suffering he sees about him. He asks Eurypylus whether the Greek forces can prevail against Hector’s army. Eurypylus says they cannot. There are too many wounded and their forces are tired. He asks Patroclus to help him remove the spear from his thigh, since Patroclus has some experience in healing. Patroclus helps remove the spear and promises Eurypylus that he will return to Achilles, and that he will not let him down. Patroclus, at this point, is clearly persuaded by Nestor’s plan.

While Book 11 focuses on a lot of fighting, it is far more consequential to the progression of the plot than Book 10. The last section of this book leaves the fighting behind as Machaon is wounded and Achilles dispatches Patroclus to confirm his identity. Patroclus’ meeting with Nestor is fateful, since the proposal Nestor makes – that Patroclus should fight in Achilles place – is the catalyst for the tragic events that propel the second half of Homer’s poem.

Book 11 is also significant because it shows the Greek forces suffering setbacks. Two important cases are the wounding of Diomedes in the foot and the wounding of Eurypylus in the thigh. These are significant moments because they are both central to the plot and the key issues of the poem.

First, Diomedes has been a major force on the battlefield since Book 5. In Book 5, Athena has given him the ability to distinguish gods from mortal men, and his effectiveness in battle is only second to Achilles. In fact, Diomedes acts like a surrogate for the absent Achilles, who is semi-divine, for much of the story while Achilles waits out the action. In Book 5 Diomedes was the target of another archer, Pandarus. Pandarus said of Diomedes:

Pandarus, the best archer the Trojans had, could not inflict a substantial wound against Diomedes because he is protected by Athena.

So Diomedes’ wound in Book 11 is significant, first, because he is forced from the battlefield because of it. The effectiveness of Zeus’ anger against the other Gods is apparent in Diomedes’ case: “The other gods kept clear, at their royal ease.” (Book 11 line 87) The gods have been warned not to interfere and Diomedes no longer enjoys the protection he formerly had. While Pandarus could not strike a significant blow, Paris, who has been portrayed as a coward in Book 3 when he fought Menelaus, can. Helen stated:

Diomedes expresses similar sentiments about Paris:

So, while Paris remains a figure of contempt, we understand that Diomedes’ wounding is a sign that fate has turned against the Greek forces and the gods are absent.

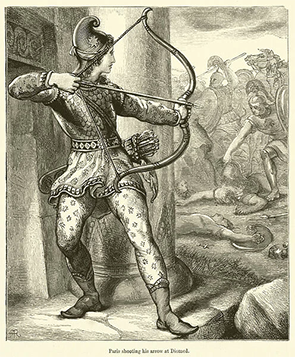

The second significant aspect of Diomedes’ wounding lies in the nature of the wound. This 19th Century engraving by Jean-Michel Moreau gives a sense of it:

Homer describes the moment Paris shoots Diomedes:

As a surrogate for Achilles, Diomedes’ wound foreshadows Achilles eventual death, famously wounded in the heel, also from an arrow by Paris. Given that Achilles’ death is not described in The Iliad, the wounding of Diomedes is probably as close as we come to the event.

Paris is barely present in this book, but he also inflicts a wound on Eurypylus too as he tries to defend Ajax. While Diomedes wound foreshadows the wound to be suffered by Achilles, Eurypylus’ wound is the focus of the last lines of this book as Patroclus removes the shaft from his thigh. Patroclus has already been moved by Nestor’s appeal to join the fight. But it is this last thing – Eurypylus’ assurance that the Greeks cannot win and his wound and many other wounds that Patroclus sees, that helps him determine what he will do.

Many others are wounded in this book. Also of significance is the wound suffered by the healer, Machaon. The need to prioritise his safety speaks to the desperate position of the Greeks. Idomeneus justifies his removal from the battle to Nestor:

I have found very little art that represents the events of Book 11 of The Iliad. Part of the problem, I think, is that much of the book involves heated battle which would look like other battles, and therefore would appear generic. There are key moments in the battle, but they don’t supply the same opportunities as those in other books. The wounding of Diomedes is important, given that it foreshadows Achilles own wounding, but artists tend to therefore focus on Achilles’ death and Diomedes is overshadowed.

As for the latter part of the book in which Patroclus visits Nestor, we have a pivotal moment in the story, but art around Patroclus tends to focus either on his later fight with Hector or his death.

The following are engravings which depict the moment Paris targets Diomedes and Patroclus’ tending to the wound of Eurypylus.

This rather unexceptional drawing foregrounds and emphasises Paris through the use of a heavier pencil. There are clues in the picture to suggest the artist is unsympathetic to Paris. First, is that the artist takes such pains to establish that Paris is separate from the battle. The large round column he hides behind dominates the scene and a door to the left suggests a means of escape.

Paris’ clothing is also peculiar. It is dissimilar to all other figures in the image. Paris’ clothes appear courtly (almost like a court jester?) and his hat is effete. It is difficult to credit him as a serious warrior. His stance is also extreme, with his body twisted to allow a shot, but also ensuring his back remains facing the danger.

This image from the 17th century is remarkable for its inaccuracy, presuming it really is a representation of Patroclus and Eurypylus. Crispijn van de Passe produced a series of engravings for Homer’s epic, so we might presume it is associated with the poem. In this case, it is meant to represent the scene in which Patroclus attends Eurypylus’ wound.

In Homer’s telling of it, Patroclus meets Eurypylus at the ships after he has spoken to Nestor. Eurypylus has left the battle, just as other major Greek heroes are forced to do in this book, because he has been wounded in the leg by Paris.

So, the first thing is that the artist’s depiction of Eurypylus and Patroclus so close to the battle is inaccurate. So, too, are their costumes and the background buildings which probably represent the artist’s contemporary society.

The presence of the dog is curious. The dog looks well fed and well cared for in this war zone, and does not looked perturbed by the events on the field of battle.

Another curios detail is that Eurypylus knees in front of the Patroclus in a manner more in keeping with a show of respect, rather than as a man seeking medical help. Patroclus seems to hold something at Eurypylus’ chest, rather than be removing an arrow. The arrow, in fact, should be drawn from his leg.

Given these inaccuracies, I think there is some chance that the engraving has been misidentified.

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!