As the title suggests, this book marks a turn in the battle as Zeus takes a more active role in the war and forbids any other god from involving themselves further.

Whereas the Achaeans were gaining confidence and the Trojans losing confidence in the previous book, this book reveals the meaning of the ominous peal of thunder heard from Zeus at the end of Book 7. Zeus calls a meeting of the Gods in which he forbids all other Gods from becoming further involved in the battle. Zeus is boastful and confident in his power, claiming he can outmatch the strength of all the other gods combined. The gods are struck silent by his boasting and threats until Athena agrees they will offer no help to the Achaeans except to suggest battle tactics. Zeus, seeing the impact his demands have had, attempts to reassure Athena that his threats weren’t serious.

But Zeus does intend to take a more active role in the outcome of the battle. He rides his battle-car to Mount Ida where he can survey what is happening. In the morning the Trojans surge out of their city, with infantry as well as cavalry and charioteers. The battle is renewed and the Trojans and Achaeans are fairly evenly matched, with large numbers killed on both sides. But at noon Zeus throws thunderbolts from Mt Ida at the Achaean forces and turns the tide of battle against them.

Paris manages to kill one of the horses that pull Nestor’s chariot with a spear, and Nestor is forced to stop to cut the horse free. This makes him vulnerable to Hector’s attack as he bears down upon the old man in his chariot. Diomedes, seeing Nestor’s danger, calls upon him to board his own chariot while Diomedes’s aides handle Nestor’s remaining team. Nestor climbs into Diomedes’s chariot and takes the reins, turning the horses against Hector. Diomedes throws a spear but misses Hector, killing his driver, Eniopeus, instead. Hector soon replaces him with another driver, Archeptolemus. Meanwhile Zeus again hurls thunderbolts to drive the Achaeans off and prevent Hector’s forces being penned inside the walls of the Achaean defences. Nestor, seeing how Zeus is set against them, calls for Diomedes to withdraw from the fight. But Diomedes is unwilling, knowing that a withdrawal will look like cowardice in front of Hector. Nestor argues that Hector will not be believed, anyway. But Hector is already taunting Diomedes’s hesitation caused by Zeus’s bolts of lightning, suggesting he is a coward by using emasculating taunts against him. But every time Diomedes tries to move, Zeus sends another thunderbolt against him. Hector, seeing that the battle has turned in the Trojans’ favour, urges his men to attack the Achaean defences and their ships. He also urges his horses on, hopeful that he will capture the shield of Nestor and kill Diomedes for his armour which was forged by Hephaestus.

Hera, seeing what is happening, vents her frustration on Poseidon, angry that they cannot turn the tide of battle back to the Achaeans’ favour. Poseidon, understanding her desire, says he has no will to battle with Zeus.

Meanwhile, Hector’s forces have breached the Achaean defences and victory seems assured. Realising the danger, Hera impels Agamemnon to rouse his men to resist Hector. But Agamemnon merely rails against his troops ineffectively. Their ships have been dragged upon the shore and lay upon their side. There is no escape. Agamemnon, in desperation, calls upon Zeus to have mercy: to at least allow the Argive forces to get away with their lives. Zeus takes pity and sends an eagle clutching a fawn as a sign and the Achaean forces rally. Diomedes first crosses into Trojan lines to kill a Trojan captain, Agelaus. Others are inspired by Diomedes and follow him. In particular is the archer Teucer who, protected by the shield of Greater Ajax, begins picking off many Trojan warriors with his arrows. Agamemnon, excited by Teucer’s success, promises him a first choice of the spoils of Troy when they finally take the city. Teucer is confident in his ability, but he is frustrated by his failure to take Hector down. He tries several times and each time he kills someone else, including Archeptolemus, Hector’s driver who replaced Eniopeus when he was killed by Diomedes’s spear. Hector, infuriated, leaves his chariot and pitches a heavy rock at Teucer. He strikes him in the neck. Teucer is wounded and has to be carried from the field of battle.

Once again, Hector’s troops have the upper hand and he forces the Argives back across their trench. The battle is becoming a rout. Hera, calls upon Athena to witness what is happening. Athena says she regrets helping Heracles, Zeus’s son, in his labours for Eurystheus. She asks Hera to harness horses to a chariot while she puts on her battle armour.

But Zeus sees Athena and Hera preparing to leave Olympus and sends Iris, his messenger, to warn them he will destroy their horses and will wound them so badly with lightning bolts that their wounds will take years to heal. Zeus’s threat works. Hera tells Athena to abandon their plan.

Meanwhile, Zeus returns to Olympus, where he mocks Athena and Hera for their presumption to defy him. He says that had they gone ahead with their plan he would have banished them from Olympus. Athena gives no response while Hera repeats their original promise that they will offer no help to the Achaeans except to suggest battle tactics. Zeus says he will return to the battle the following day, but makes a prophetic statement, that Hector will never quit fighting until Achilles re-enters the fight, battling for the body of Patroclus.

Night descends and the battle ends for that day. Hector, now full of confidence, addresses his troops. He expects the Argives to attempt to flee from the beach in their ships under cover of night. He instructs that fires be lit all over Troy and throughout their camp and field of battle. He hopes to catch the Argives as they try to leave and inflict more casualties upon them. At the same time, he wants fires throughout Troy to prevent any raids by small bands. He anticipates a climactic personal battle with Diomedes in which either he or Diomedes must die. He does not seem to consider Achilles as a potential rival.

That night, the fires blaze on the plain beneath Troy and throughout the city.

In Book 7 the Greeks were ascendant while the Trojans desired peace. By the end of Book 8, the Greeks have almost suffered complete defeat. Zeus’s intervention in the battle and his injunction against other gods helping the Achaean forces has changes everything.

Zeus is a capricious and changeable character. In previous books he has expressed a desire to avoid conflict with his wife, Hera. Now, he openly opposes Hera, Athena and all the other gods with the justification that “. . . all the more quickly / I can bring this violent business to an end.” (Book 8, lines 9-10). However, Zeus’s purpose is not always consistent, nor are his moods. While the Greek ships are under threat in this book and a great deal happens in the world of the mortals, it is Zeus’s character that directs much of the action in this book. The following are extracts that illustrate these various moods and purposes:

Zeus’s boast seems hyperbolic except that he is the head of the Olympian gods. His image of the golden cable hanging from Olympus to earth is, upon which all the gods of Olympus as well as the weight of the earth itself would fail against Zeus’s, is nothing less than a celestial tug-o-war, the image intended to convey one thing – strength – and achieve one goal, the compliance of all the Olympian gods. The fact that we are meant to take this boast literally is hinted at later in the book when Hera encourages Poseidon to rise against Zeus. Poseidon replies, “The King is far too srong – he’ll crush us all.”

Zeus’s reassurance to Athena seems indicative of two things. First, is his changeable nature. His reassurance comes directly after he has made threats against the gods if they do not bend to his will. Second, we see Zeus both as a ‘statesman’ when he deals with the gods together, and as a ‘Father’, a title used several times in Book 8 by the gods when the speak of Zeus. Athena is Zeus’s daughter, and his more compassionate tone is meant to reassert his relationship with his daughter, who, as a god, has also received his warning. Even so, later, when Athena and Hera choose to defy Zeus, it is Athena who is specifically threatened again:

while he merely accepts Hera’s defiance:

In Book 8 Zeus deploys his thunderbolts and thunder to terrify the Achaeans and change the course of the battle. Instead of descending into the battle as we have seen other Gods like Ares and Athena do previously, he stands atop Mt Ida and throws his lightning bolts into the melee. The lightning bolts symbolise Zeus’s strength and divine power.

Despite Zeus’s claim that he intends to end the war swiftly, his capriciousness is again on display when he decides to spare the Achaean army, right at the point when the Trojans could destroy it and end the war. Agamemnon weeps and prays for mercy from the god, and Zeus grants it by sending an eagle holding a fawn. The eagle drops the fawn at a shrine where the Achaeans have worshipped, thereby sending a propitious sign which inspires them to rally and fight. It is at this moment when Diomedes rushes into the Trojan lines, followed by nine others, including Greater Ajax and the archer, Teucer, who help rescue the Achaeans from certain defeat.

Zeus sends his messenger, Iris, to deliver a warning to Athena and Hera not to leave Olympus and join the battle again on the Achaean’s side. The goddesses comply immediately. Nevertheless, it is in Zues’s nature to mock, and he returns to Mount Olympus immediately to do this. Despite his overwhelming power, scenes like this seem to belittle the god, who employs the tactics of a man or child who has less power than he does.

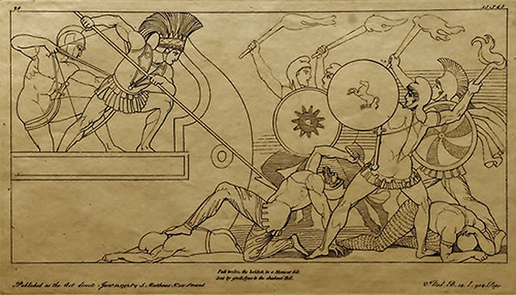

A central aspect of this book is Zeus’s decision to assert his power over the other Olympian gods and the battle. The book begins with his forbidding further involvement of other gods in the battle. Nevertheless, Hera and Athena feel compelled to help the Achaeans in what has become a slaughter of their forces. This image by Crispijn van de Passe illustrates the moment from Homer’s poem when Zeus sends Iris forbidding Hera and Athena from leaving Olympus to help the Achaean forces. His representation of the various aspects of the story at this point – the mortal conflict at Troy, Zeus’s use of his thunderbolts and stopping the two goddesses – feels clumsy. The arched rock and the sweeping cloud upon which the gods sit are distracting and dominate the scene too much. They are meant to illustrate different moments in the story rather than a scene, per se. But apart from the weird management of the space in the image and the military uniforms of the seventeenth century worn by the mortal forces, de Passe’s representation is also narratively inaccurate. The upper half of the image depicts two moments in the story: Zeus’s use of his thunderbolts in the battle and then the two goddesses being stopped. But we see by Zeus’ representation in the first instance that de Passe has Zeus stopping the goddesses himself, rather than Iris, his messenger, who is female. It is difficult to determine what point in the battle the lower images represent, except that the left lower panel seems to show Achaean forces being harried by Zeus’s thunderbolts, which gives some connection to the left upper images which depicts Zeus wielding them.

The following quote is an extract from Iris’s speech to Athena and Hera, repeating Zeus’s warning.

Book 8 is a low point for the Achaean forces as Zeus turns his might against them. But they are given a brief ray of hope when Diomedes charges into the Trojan forces and others are also inspired. One of their most decisive moments is the partnering of Greater Ajax and Teucer, an archer. Ajax uses his shield to protect Teucer as he reloads his bow, and then Teucer emerges, killing Trojans with every shaft. Their partnership is described by Homer in the following lines:

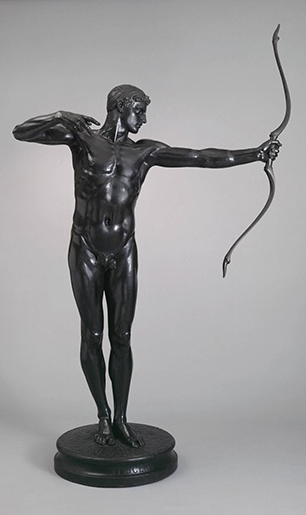

Thornycroft produced several works based on Teucer, including drawings, engravings and statues. This bronze statue is fairly typical of Thornycroft’s representation of Teucer. Teucer gains minor heroic status for his brief partnership with Ajax. However, Thornycroft’s statue is not an accurate representation of Teucer based on Homer’s story. While Teucer’s hiding behind Ajax’s shield is strategically sensible, it does not have the same heroic quality we have seen in previous fights, where warriors stand unguarded as spears are thrown, or stand toe to toe with their opponents. This impression isn’t helped by Homer’s description of Teucer hiding behind Ajax’s shield, likened to a child hiding under its mother’s skirts. Instead, Thornycroft’s representation captures some of the heroic quality Teucer is evidently meant to have, if we consider Agamemnon’s enthusiastic praise and his desire to reward Teucer. Thornycroft has Teucer stand tall, posed in the style of classical Greek models, at the point where his arrow has just been released.

This second image from Flaxman’s Iliad shows the defence of the ships, with two figures, purportedly Greater Ajax and Teucer, working in unison. Here, Ajax uses his spear to fend off attackers from the ships and his archer. But the image is a reasonable representation since the ships are the Greeks’s last line of defence, and it is Agamemnon’s cry to defend the ships which causes Diomedes to lead the charge.

Nikolaos Loukanis produced a translation of The Iliad into modern Greek in 1526. This illustration of chariot warfare is from Loukanis’s edition. Some of the most gripping moments in the battle happen in or around chariots. For instance, In Book 8, Nestor falls into danger when one of his horses is killed and he must stop to free it from his chariot. Hero’s often fight from chariots in the general fighting and leave their chariots to fight other named heroes.

Unfortunately, this older representation of chariot warfare is quite primitive in its skill. Its figures feel like cardboard cut-outs and the effect is somewhat comical. The second horse, for example, with its head bowed to the ground, seems to appear from nowhere from behind the first horse. Where is the rest of its body. Nevertheless, the image is charming, and the style is still capable of conveying story elements, if not the grandeur of its theme.

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!