Book 3 of The Iliad left the resolution of the fight between Menelaus and Paris somewhat unresolved. Paris was carried back to Troy by Aphrodite and Menelaus was left on the beach, looking for him and declaring victory. The title of this fourth book says it all. The truce that was negotiated in Book 3 on the understanding that Menelaus and Paris would act as champions to resolve the entire conflict, is broken.

This book begins with the gods in Mount Olympus. Zeus mocks Athena and Hera for their support of the Achaeans, and with Aphrodite’s action of plucking Paris to safety. He declares Menelaus to have been the victor against Paris. Hera responds, asking how Zeus can frustrate her efforts when she, too, is a god. She says he can do as he pleases, but he will receive no praise from the other gods for his actions. Zeus responds, saying he knows of her desire to destroy Troy. He tells her to do as she pleases, to destroy Troy if she must, but not to make the mortals’ conflict a reason for conflict between them in the future. He loves Troy beyond any other city, but in the future she is to acquiesce to his will if he decides he will act against cities she loves. Hera responds, saying that Argos, Sparta and Mycenae are the three cities she most loves, and he can destroy them if he will. Besides, she knows his strength exceeds hers and she couldn’t stop him if she wanted. Having reached this agreement, Hera asks Zeus to send Athena to make the Trojans break their truce.

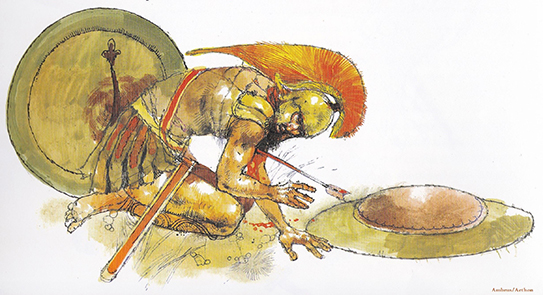

Athena descends to the plain where the armies are arrayed and takes the form of Antenor’s son, Laodocus. She searches out Pandarus. Pandarus is a famed bowman. In Book 2 we are told he holds “the bow that came from Apollo’s own hands” [line 938]. In this section of Book 4 we are told the story of the bow: that it came from the horn of a goat Pandarus killed while hunting. Disguised as Laodocus, Athena challenges Pandarus to take a shot at Menelaus. Pandarus takes up the challenge. He is shielded by other soldiers as he braces his bow against the ground to take a long shot. His shot is true, and it would have killed Menelaus, except that Athena, not wishing Menelaus dead, deflects the arrow to the most protective part of his armour. Still, the arrow wounds Menelaus in the groin and he bleeds profusely.

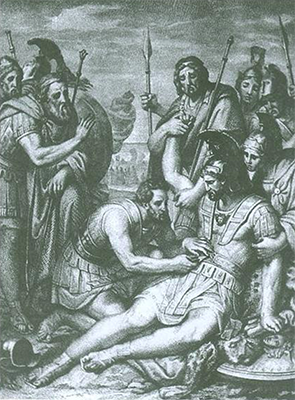

Agamemnon is incensed and swears Troy’s destruction. At the same time, we see the weakness of Agamemnon’s position. He fears that if Menelaus dies the armies will return to Greece because they cannot return Helen to him. Agamemnon understands that this will diminish him as a king, because he will have failed. Menelaus alleviates Agamemnon’s fears by confirming that his wound is not mortal. Agamemnon calls for a healer, Machaon, son of Asclepius, who removes the arrow and treats Menelaus’s wound.

Now the Greek forces prepare for battle. Agamemnon moves through the troops, rousing them with the justness of his cause and railing against any who appear to be unwilling to fight again. Idomeneus reasserts his commitment to Agamemnon’s cause, and he and Meriones help rally the troops. The armies of the two Ajax’s (‘Great’ and ‘Little’) form up behind their commanders. Agamemnon praises them, saying that if all his forces were as good as them, Troy would fall in an instant. Nestor gathers his forces and ensures any men he deems to be cowards are positioned in the centre so they cannot escape. Agamemnon praises Nestor while acknowledging his age. Nestor admits that his own physical prowess has been diminished by age. Meanwhile, Agamemnon berates Menestheus and Odysseus for being behind all the other commanders in their preparations. But it turns out they have only just heard the call to arms. Odysseus assures Agamemnon that he and his men will engage the Trojans fiercely. Agamemnon withdraws his criticism. But he finds cause to criticise Diomedes whom he finds standing behind his troops. Agamemnon recalls that Tydeus, Diomedes’s father, was renowned for bravery. He won respect in the campaign against Thebes and he is said to have fought off fifty men in an ambush. Sthenelus, who is beside Diomedes, argues that they have already proved their worth in former campaigns, and that their fathers had been reckless. Diomedes tells Sthenelus that he respects Agamemnon’s actions to rally the troops: that Agamemnon bears all the risk in the war, either to win glory or accept the grief of massive losses. Diomedes now shows himself to be ready for the battle.

As the forces mobilise, Homer contrasts the discipline in the Achaean army and the lack of discipline in the Trojan army. The Achaeans move quietly so they can hear their commanders’ orders. The Trojans move without discipline and have no way of hearing commands.

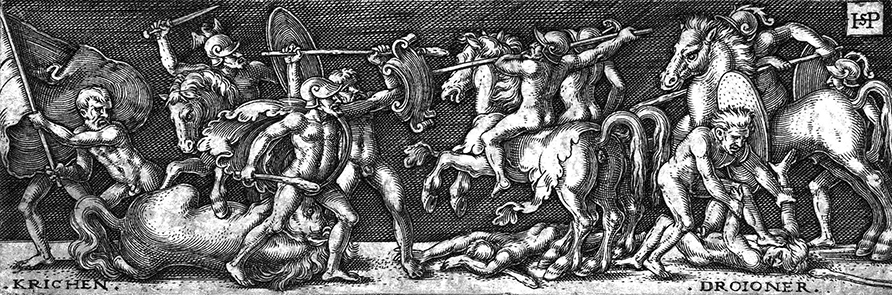

Now, the two armies clash.

Homer tells the story of individual fighters. Antilochus is the first to kill a Trojan commander, Echepolus. Elephenor is killed by Agenor as he attempts to strip the gear from Echepolus. Telamonian Ajax [the ‘Great’] kills Simoisus of Troy, so young he has not wed. Leucas, Odysseus’s comrade, is killed by Antiphus, who has missed Ajax with his spear. In retaliation, Odysseus kills Priam’s bastard son, Democoon.

The Trojan forces begin to fall back under the Achaean attack. But the god Apollo urges them to fight back, pointing out to them that Achilles and his men are not even in the battle. Athena, in turn, spurs the Greek forces on.

Meanwhile, Diores, a Trojan leader, suffers a gruesome death after his leg is shattered by a rock, thrown by Pirous, who then spears him in the navel. Pirous is then killed by Thoas, who pierces him in the chest with a spear. But Thaos cannot strip the armour from Pirous because his comrades protect his body.

This Book ends with huge numbers of Trojan and Achaean dead on the battlefield, together.

The actions of the gods are revealed to be detached and self-serving in this book, despite their professed love of certain people or peoples. The truce between the Trojans and the Greeks is broken when Athena is sent to break it. She persuades Pandarus to wound Menelaus with his bow. The decision to do this comes after an exchange between Zeus and Hera. Zeus claims to love the Trojans better than any other people (“I honor sacred Ilium most within my immortal heart” - Book 4, line 54) yet he is willing to sacrifice the Trojans to maintain peace with Hera. But he also tries to persuade her not to act by threatening cities she loves. The mortals are shown to be used like pawns in a game of chess between the gods.

The following are the lines devoted to this pact in Fagles’s translation:

In Fagles’s translation Zeus reasons with Hera, first to suggest that the proportions of her rage are overblown, and to portray himself as the one attempting conciliation. His threat to destroy cities loved by Hera comes as a warning of the possible consequence of Hera’s actions. Zeus tells Hera to “do as you please” and says “I gave you this”. The potential violence he describes is moderated by qualifiers, “if” and “might”, that place the burden of responsibility of Hera if she acts. Here, Zeus speculates what might satisfy Hera’s desire for vengeance, rather than using imperative language. The meaning is clear enough, but Fagles’s translation characterises Zeus’s bargaining as a strange blend of conciliation and demand (“don’t let this quarrel breed some towering clash” / “never attempt to thwart my fury”).

Yet if we look at Alexander Pope’s earlier translation (1715), the terms of the bargain have a different tone:

Pope’s Zeus speaks in imperatives – “leave the skies”, “Burst all her gates”. His intention is less that he might remain at peace with Hera in the future, as characterised by Fagles, but that he should rather have peace, free of Hera’s demands. He treats her like a petulant child whose actions are inevitable. He is less conciliatory and more threatening. Pope characterises Hera’s unfettered violence and Zeus’s possible retaliation. Fagles’s Zeus is bargaining with Hera. He is suggesting what Hera might do, but also warning her of consequences. The correctness of this seems apparent when we consider Hera’s response: she accepts that Zeus will raze cities she loves, so long as she can be free to destroy Troy:

Pandarus is the bowman who is persuaded by Athena to shoot at Menelaus and thereby break the truce between the Achaeans and Trojans. Athena chooses Pandarus because of his famed skill with the bow, which Homer tells us in Book 2, was gifted to him by Apollo. But in this book we are told that Pandarus made his bow from the long horn of a wild goat he killed while hunting. It is hard to reconcile the discrepancy, but it might be explained in two ways. First, among other things, Apollo was the god of archery. He was also a patron god of Lycia, the town from which Pandarus came.

Apart from the fact that he is tricked by Athena and that his archery skills are great, there is not much more to say about Pandarus here. Except that his character underwent a strange transformation in later ages. In Giovanni Boccaccio and his Il Filostrato (1338) Pandarus is essentially a good character who brings Troilus and Cressida, two lovers, together. Chaucer, who used Boccaccio as a source, transforms Pandarus into a manipulating villain. By the time Shakespeare wrote his Troilus and Cressida, Pandarus was established as a middle-aged man who brings the two lovers together, but he is manipulating and creepy, and tries to pressure them into bed. When Troilus says he is speechless at the sight of Cressida, a typical lover’s reaction to beauty, Pandarus tells Troilus, “Words pay no debts, give her deeds.” (III.2.53) His meaning is clearly bawdy. When he returns to the room where he has left the lovers he remarks, “What, blushing still? Have you not done talking yet?” (III.2.99) Further on, he becomes more explicit: “I will show you a chamber with a bed; which bed, because it shall not speak of your pretty encounters, press it to death.” (III.2.203)

This is a strange transformation from Homer, but there still is a dim suggestion of Homer’s Pandarus in Shakespeare’s representation. He offers to sing a song to Helen and Paris:

The reference to the bow recalls Homer’s Pandarus, but it is obviously a reference to the role Pandarus now plays, as a kind of cupid bringing lovers together. Pandarus, himself, draws a more explicit link between himself and cupid at the end of Act 3 Scene 2:

As a result, the modern word “panderer” usually refers to someone who tries to arrange unions or sexual liaisons between others, and “to pander” means to give someone what they want, even if it is not in their best interests.

This image, featuring Zeus holding his sceptre in one hand and lightning bolts in the other, portrays the exchange with Hera that results in their pact to allow for the fighting between Trojans and Greeks to be resumed. De Passe’s representation of the gods and the conflict in one frame is quite odd. The cloud formation the gods sit upon seems like a solid feature of the landscape itself.

Francesco Nenci’s illustration shows the moment when Machaon removes the arrow from Menelaus’s wound. Fagles’s translation of Homer implies the wound is to his genitals, suggesting an erotic wound that matches his emasculation by Helen’s infidelity:

Menelaus’s emasculation is further suggested by Homer’s following image: “the fresh blood went staining down your sturdy thighs, your shins and well-turned ankles”. Menelaus’s wound not only has erotic implications, but suggests menstruation. Menelaus has not only been wounded, but Achaean honour and masculinity have been challenged.

The battle featured in the last section of Book 4 is clearly of an enormous scale, leaving masses of dead on both sides of the conflict. This engraving by Beham attempts to convey the violence of the battle, but it is curious because it follows the convention of many classical representations in that its figures are nude. One of the things that is striking when reading Homer’s battle scenes is the importance placed upon stripping enemies of their armour. Elephenor is killed by Agenor as he attempts to strip the armour from Echepolus. Thaos fails to strip the armour from Pirous’s corpse because his body is protected by his comrades. Obviously, stripping armour from the vanquished served to humiliate the defeated and provide a trophy for the victor. I imagine, given the difficulty to find the resources needed and the skill to produce armour, armour would have been a valuable commodity, too.

Later in The Iliad, armour plays a critical role in the plot.

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!