In this Book Achilles, grieved to hear the news of Patroclus’ death, is determined to seek vengeance on Hector. But first, his armour and weapons must be forged anew.

Under orders from Menelaus, Antilochus makes his way back to the ships to deliver the news to Achilles that Patroclus is dead. But when he finds him, Antilochus discovers that Achilles already has a deep foreboding. Achilles recalls the prophecies that said the best of the Achaeans would fall at Troy, and he is certain Patroclus has died, disobeying his instructions by pushing on to take the city. Antilochus confirms this and Achilles bursts out in grief, pouring ash, soot and filth over himself, and tearing his own hair. Female captives join in the anguished lament by crying out. The grief is so strong that Achilles mother, the sea nymph, hears it, and all the Nereids join her in in an anguished dirge. Thetis realises that she will either never again embrace her son, or if she does see him again, he will always be racked with anguish.

Thetis leads the Nereids to the shore of Troy and finds Achilles sobbing. She asks what has upset him, since all he has hoped for has come to pass in the war, so far. Achilles explains that Patroclus is dead. In his misery he regrets that his mother ever gave him birth, or that she was made to endure the pain of a union with a mortal man. He says he has lost the will to live, except that he wishes to kill Hector. Thetis reminds him that his own death will quickly follow Hector’s. Achilles does not care. He feels like a useless weight sitting by the ships. He resolves to go meet Hector, but Thetis reminds Achilles that his armour and weapons are now in the possession of Hector. She tells Achilles to wait until she returns with new-forged armour and weapons from Hephaestus.

Meanwhile, the fight for Patroclus body has not yet stopped. The Achaeans still cannot manage to drag the body out of range of the fighting. Hector, himself, has three times seized the body by the feet to take it, and he has been beaten off three times by the Aeantes, Greater and Lesser Ajax. But just as it looks like Hector has a real chance of retrieving the body, Hera secretly sends Iris to Achilles with a message. She tells Achilles about the danger to Patroclus’ body and says he will be shamed if Hector succeeds. Achilles is conflicted. He says he has promised to wait for his mother’s return with armour and weapons. Achilles is told to go to the broad trench where the enemy will be able to see him, so that they might be struck with fear at the sight of him. Achilles obeys. Athena places a shield over his shoulder, places a cloud on his head as a crown and makes a fire spring from it. When Achilles appears before the Trojans he stands apart from the Argive ranks, to obey his mother’s command, and a flame leaps from his crown into the sky. When he cries out the Trojans are struck with fear, which gives the Argives the chance to finally pull Patroclus’ body from the battle. Achilles joins his comrades to retrieve the body.

The sun goes down. In the Trojan camp a debate begins. Polydamus argues that the Trojan forces should be pulled back to the city to defend it. The sight of Achilles has spooked him. He believes Achilles will fight to take the city and their women. If they stay where they are many more Trojan soldiers will die. Polydamus believes if they defend the city from within the Greek forces will never be able to take it.

Hector responds. He is sick of defending. He points out that many of Troy’s treasures have already been sold off to support the war. Instead, Hector urges that they should again attack the Argive ships at daybreak. The Trojans roar their assent for Hector’s plan.

In the Greek camp the atmosphere is less triumphal. Achilles is torn by his failure to keep his promise to Patroclus’ father, Menoetius, to keep his son safe. He makes a resolution to delay Patroclus’ funeral until after he has killed Hector. Patroclus’ body is bathed, anointed and his wounds closed. A white shroud is placed over the body and then all night long the Argives are led by Achilles in a dirge for the fallen Patroclus.

Zeus, seeing all this, realises that Achilles has been spurred to act, and he blames Hera. Hera responds that even a mortal man will act to help a friend, so why would she, with greater wisdom than mortals, not act against the Trojans.

Meanwhile, Thetis reaches Hephaestus’ house in Olympus and finds him working at his forge. Charis, Hephaestus’ wife, welcomes her. Hephaestus recalls the debt he owes to Thetis. She helped to save his life when he was cast from Olympus by Zeus. Thetis and Eurynome gave him a place to recover for nine years. He is eager to help her in any way he can.

But first, Thetis is overcome with emotion. She speaks of the unhappiness of her relationship with Peleus, Achilles’ father, a relationship forced upon her by Zeus, but says her grief is now worse. She speaks of the pride she took in Achilles as he grew up, only to lose him to the Trojan expedition and see him spend his final days in anguish. She tells Hephaestus the whole story of how things have come to this pass, starting with his loss of Briseis to Agamemnon. She asks Hephaestus to forge new armour for Achilles. Hephaestus promises to forge the armour. He begins first with what will be Achilles’ shield.

Hephaestus forces a massive shield which is described in detail. Upon its surface it bears numerous scenes that reflect aspects of the lives of people during this time. Homer describes each scene in turn:

Hephaestus also forges a breastplate, a helmet and greaves for Achilles, and lays the armour at Thetis’ feet. She leaves with the armour, heading back to Troy.

The final section of Book 18 of The Iliad is a detailed description of the shield Hephaestus creates for Achilles. First, Homer describes the construction of the shield. It has five layers of metal. Stephen Fry in Troy claims that two layers were bronze, two of tin with a central core of solid gold. However, Homer is not so precise. He tells us that Hephaestus throws “durable bronze and tin and priceless gold and silver” into the blaze of his furnace as he prepares his forge.

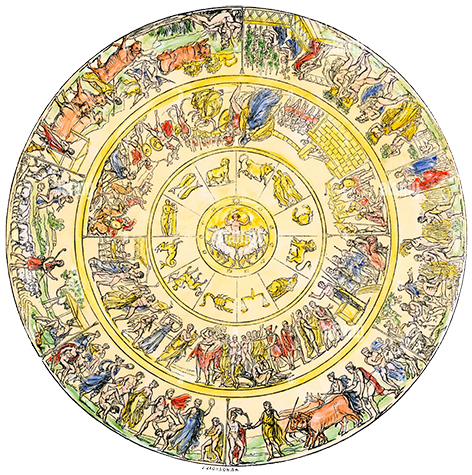

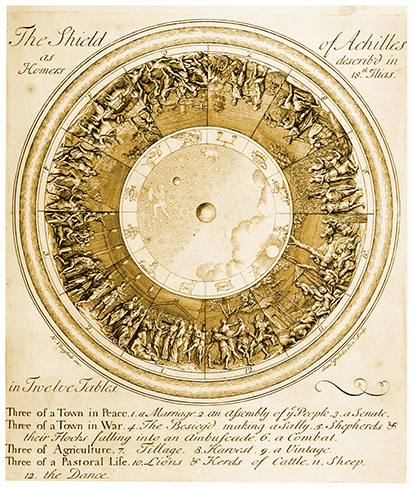

Since the early eighteenth century there have been attempts to create versions of Achilles shield based upon Homer’s description. Homer describes various scenes that depicted experiences of life as his audience would have known it, set within a cosmological universe. Homer’s description of the shield is the first known example of ekphrasis, a rhetorical device in which the poet describes a work of art in detail so that the reader can imagine it visually. A drawn version of the shield appeared in Alexander Pope’s 1715 edition of The Iliad, which can be seen under “Representations in Art”. It divided the scenes in the shield around the outer rim. However, Angelo Monticelli’s 1820 design, which has been copied extensively, displayed the scenes in sectioned concentric circles.

This coloured version of the shield is a nice representation of what Homer describes. There are other more elaborate interpretations, including actual shields that have been produced with beautiful details. But Monticello’s version provides a visual mnemonic of the poem. Starting at the centre is a representation of the universe. The next circle represents cities. In one, weddings and a court case are taking place, and a second city is under siege. The outer circle represents scenes of more bucolic life, wherein the activities of the year – ploughing, harvesting, herding and celebrating – are depicted. The final element of Achilles’ shield, the River Ocean, which is the outer border of the shield, is not depicted well in the image, and so I have not included a visual detail of it below.

Monticelli’s representation of the cosmos seems somewhat simplified compared to the description Homer gives. Fagles’ translation of Homer identifies the sun, the moon, constellations, the Pleiades and the Hyades, Orion, and the Great Bear. In this panel the signs of the twelve zodiac form the outer ring, while the sun is represented by Helios in his chariot, being drawn by his four steeds at the centre. The myth was that Helios dragged the sun behind his chariot across the sky each day, which accounted for its apparent movement.

Homer describes images from two cities on Achilles’ shield. The following two images represent those two cities and together they form the panels that encircle the heavens in Monticello’s version of the shield. In the first image I have applied a very pale yellow to the right of the image to delineate between the wedding scene on the left, and the trial scene on the right:

The left side of this panel represents the weddings that Homer speaks of in the Shield of Achilles. In this scene young women are led by their lovers to their wedding with raised torches, to the sound of music on a lyre. The scene is faithful to the spirit of Homer’s description:

Homer also describes a dispute between two men. This is the scene on the right side of this panel. A kinsman has been murdered and his relation refuses the blood-price for the murder. The disputants employ judges to decide the matter and their cases are made while others look on. The men seated at the right of the image are the city elders who “sat on polished stone benches, forming the sacred circle, grasping in hand the staffs of clear-voiced heralds”.

The second city described by Homer is besieged. Homer’s description of the situation sometimes exceeds what one might assume to be possible to represent visually. For instance, the besieging army is said to be in dispute over whether the spoils of the city should be kept by the army or shared with the people of the city. The people of the city send out their own army. Two of their scouts manage to attack shepherds and their flocks, which rouses the ire of the besieging army. The two armies clash next to a river.

In this scene Homer describes a soldier “hauling a dead man through the slaughter by the heels”, which recalls Hector’s attempts only 450 lines before, to drag aware the corpse of Patroclus: “[he] seized his feet from behind, wild to drag him off”. The similarity makes it difficult to ignore the parallels between this besieged city and the city of Troy whose soldiers have left the protection of the city to face the Greek forces in the field.

The scene described by Homer is the most complex in this ecphrasis, and therefore the scene on the shield is more complex, although it is difficult to identify specific details in the drawing. The different elements of the drawing should be understood to represent different elements of the city’s story rather than a representation of a moment. Therefore, we see soldiers both behind the city walls as well as marching forth. The scene on the far right may represent the attack made against the herd of oxen and sheep. Dominating the centre of the panel is a male and female figure. Their representation is unambiguously from the following lines:

So the two figures are Ares, the god of war, and Pallas Athene.

The outer ring of panels represents scenes more bucolic in nature – scenes of ploughing, harvest and celebration. There has been a progression from the inner ring of the cosmos, the middle ring of the cities, to the outer ring of the agrarian world.

Homer describes a fallow field that is being tilled for the third time in preparation for planting. As each man finishes a length of the field up and then back, they are given a cup of wine to drink, as represented at the left side of the panel.

Homer describes the harvesting of a crop as a king watches his workers. They cut the crop with scythes and others sheaf the grain with rope. At the right of the panel can be seen the king, sceptre in hand. To his left we see a worker with a hand scythe. Left again, we see the crops being bound, and left of that we see “a great ox they had slaughtered” being prepared for the harvest feast. This is a fairly accurate representation of the scene Homer describes.

Homer describes a luscious vineyard surrounded by a ditch and “a fence in tin”. The scene is joyous, with the hint of nascent sexual potential associated with the fecundity of the vine as well as the “girls and boys, their hearts leaping in innocence”. Homer tells us that “among them a young boy plucked his lyre”. This is another sketch that is very faithful to Homer’s description.

Homer describes a scene in which drovers take their cattle out to pasture, attended by their dogs. However, the lead bull is attacked by a pair of lions. The herdsmen try to fend off the lions and are helped by their dogs, but,

The lions can be scene devouring the bull in the top left of the panel while the herdsmen and dogs try to fend them off. As before, the drawing represents more than one moment from the scene. At the right of the scene we see the herdsmen when they first lead their cattle out to pasture.

Homer says little about this scene. This is everything he says about grazing sheep:

Apart from the Ocean River, which girdles the shield but is not represented in this drawing, the dancing scene is the final scene. This is a joyous occasion. Young boys and girls dance and flirt, exchange gifts and wear fine clothes, while a crowd watches them. We are also told that a pair of tumblers moved among them: they “dashed and sprang, whirling in leaping handsprings, leading on the dance”.

Homer takes at least a hundred and fifty lines to describe the magnificent shield created by Hephaestus for Achilles. That Hephaestus makes the effort and Homer gives us such detail imbues the shield with significance.

What it tells us about Hephaestus

First, we understand that the shield represents the gratitude of Hephaestus for Thetis saving him when he was thrown from Olympus by Zeus: “So I must do all I can to pay her back, the price for the life she saved…” But the level of detail in Homer’s description is also a tribute to the level of skill that Hephaestus displays. In his description of the fields which are ploughed, Homer describes the earth that is churned by the plough:

Hephaestus’ skill is such that despite the precious metals with which he works, he is able to achieve that most realistic of effects, even when it is the earth of a ploughed field. Such verisimilitude is a testament to his skill. We are also told that Hephaestus “brought all his art to bear” in his representation of the dancing circle. When we look at the detail we begin to understand why. Though he works with metal Hephaestus must render the look of the beautiful young girls and boys, their luscious flowing hair, the texture of their finespun tunics, the daggers that hang on the boys’ belts, the oxen they exchange as gifts, and capture the movement of the figures as well.

What it tells us about Achilles

Achilles is the foremost fighter of the age, but he has lost his armour when it was teken from Patroclus’ body. Hector has assumed the mantle of Achilles by wearing his armour. At present he is the foremost warrior on the field of battle. But the magnificence of Achilles’ new shield and armour foreshadows the renewed role he is about to take on the battlefield, and his defeat of Hector.

The World of the Trojan War

The shield represents the known world of this time, cosmologically, strategically, socially and economically. The scenes of the city represent moments when people come together – weddings and trials – as well as the strategic advantage of congregating within cities, for defence. Nevertheless, the reality is that the economy of this period is heavily dependent on agrarian activities like farming and animal husbandry, and we sense that humans have not conquered the natural world in the way it has been sidelined in our modern world. Lions may still attack cattle. The shield, bordered by the River Ocean, represents the known world and seeks to encompass human experience.

It seems to me that Homer is playing with the idea of the capacity of art to represent that experience. As Hephaestus has captured a world in his shield, Homer seeks to capture the great events of a war and the scope of human emotions, strengths and weakness in the wide sweep of his epic. At least, that is how it seems. It is hard to imagine the composer of this poem not admiring the theoretical apogee of creative achievement that the shield represents.

Reflections upon the War

Given the details about the second city under siege, it is difficult not to make a comparison with the situation at Troy. The besieged city represents a relatively common experience during this age. The details are similar to Troy. The city has riches. The temptation is to hide behind its walls, but many wish to confront the enemy. The battle that takes place is also similar. Corpses are fought over, and one warrior, as has been noted above, tries to drag off a corpse by the feet, much like Hector attempting to drag away the body of Patroclus.

Another writer I read suggested that the scenes in the shield were somehow prophetic. Despite the similarities with Troy in the city panel, there I nothing I see that seems to foreshadow the outcome of the Trojan war. Instead, I see the images described by Homer as representations in the shield of the wider world and its cosmos. After all, the poem, itself, acknowledges a wider world in which the gods and nature can play their part in human affairs.

The following two paintings represent the same scene. Thetis, concerned that Achilles should not head into battle without his armour, enters Olympus and requests Hephaestus forge new armour for her son. Both paintings represent Thetis receiving the newly-forged armour.

Both these paintings, above, are wonderful for their outlandishly gaudy classical details and their rather ridiculous scenarios. In the first image Thetis gratefully clutches Achilles’ new breastplate. About her young cherubs play with the armour, suggesting how unaffected the gods are from the serious affairs of humans in which they meddle. Her robes flow back into a Mannerist sky, suggesting the high feelings of the scene. Above Thetis a cupid hovers with his arrow. It’s a detail that makes little sense, but that is nothing compared to the next painting.

The second painting by an unknown hand represents similar elements. Here we see another cupid, this time accompanied by a cherub who seems to represents war, given the flaming torch he bears. Hephaestus appears to be emerging from a cave to present Thetis with her son’s new armour. Weirdly, Thetis is reclined naked (a common classical trope, but still strange) upon a shell which seems to bear her up on the tide (even though the background shows the scene taking place in the mountains of Greece), or pushed by the male figure in the surf. Her robe is even less realistic than that portrayed in the van Dyck painting. Here, Thetis’ rob billows behind her, forming an arch to frame her, possibility suggesting her divinity.

Alexander Pope translated The Iliad and The Odyssey into heroic couplets, which may be a little alien for modern readers. However, his Iliad was long considered one of the greatest translations of the poem and it made Pope his fortune. It was published in two parts in 1715 and 1720. The above diagram is taken from Pope’s edition. I’ve displayed it here to show the different interpretation of layout to the Monticello shield I have detailed. The zodiac remains but it is far more subordinated to a more realistic representation of the cosmos. The scenes from Homer are arranged around this like a clock and are labelled below the image. The details are not easily discernible on this page, but higher resolution copies are easily found online.

This is an extract from Auden’s poem. The complete poem can be found by clicking here.

Auden attended the screening of a Nazi propaganda film shortly after the beginning of World War II. When Polish people appeared on the screen some German audience members screamed out that they should be killed. The experience left a deep impression on Auden. Years later, during the Korean War, Auden wrote ‘The Shield of Achilles’. However, he gave it a modern interpretation. If Achilles’ shield, as described by Homer, represented the world that Homer and his contemporaries knew, then Auden’s modern shield would reflect a different reality: a world that post-dated two world wars, the death camps of Germany and two atomic bombs.

The stanzas of Auden’s poem alternate between the perspective of the anxious Thetis, watching as Hephaestus works, and Auden’s description of the barren, heartless, violent world depicted on the shield. The three stanzas extracted here appear at the end of the poem and begin with Thetis’ point of view. Thetis’ expectations seem drawn from the world of Homer, particularly the dance scene that appears near the end of Homer’s description of the shield. But instead of joy and hope that many of Homer’s scenes allow – that Thetis hopes to see - Thetis instead sees “a weed-choked field.”

The world imagined by Hephaestus in this shield is nothing like Homer’s. The ragged urchin who flings a stone at the bird is morally bankrupt and emotionally hollow. Girls are raped. Other boys are knifed. This is the world inhabited by the “Iron-hearted man-slaying Achilles”; a world that pleases him. This is a world of dictators and warmongers who care little for humanity. In Auden’s hands, Achilles’ skills as a warrior are not to be admired, but deplored for the misery they cause, and the efficiency they bring to war.

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!