This book focuses singularly on the battle over the corpse of Patroclus. On the Greek side, the corpse must be secured out of respect for Patroclus, as well as Greek pride. For the Trojans, acquiring the corpse might possibly give them a bargaining chip, and will be a great boost for morale.

Menelaus witnesses the death of Patroclus and forces his way through the ranks to stand above the corpse and protect it. Euphorbus, who delivered the first spear thrust against Patroclus, stands ready to defy Menelaus. He threatens to kill Menelaus if he does not leave the corpse alone. Menelaus, in turn, threatens to do the same to Euphorbus. Euphorbus becomes impatient and attacks Menelaus, whose shield repels him. Menelaus then kills Euphorbus with a spear through the neck. Homer describes Menelaus as a lion eating its kill. At this point, no Trojan has the courage to challenge Menelaus. Apollo appears before Hector as his captain, Mentes, and urges Hector to attack, and compares the challenge to chasing Achilles’ team of horses. Hector now charges Menelaus.

Menelaus is faced with a dilemma. He is out ahead of his own lines and he risks being overrun and surrounded by Trojans if he remains alone to fight. He is also aware that Zeus is supporting Hector. He feels he would have a better chance to stand against the attack if he were supported by Ajax. Menelaus gives ground and returns to his lines. He calls for Ajax to help him defend Patroclus’ corpse.

Meanwhile, Hector is removing the armour, but also trying to remove the head of Patroclus. He intends to feed the body to Trojan dogs. But Ajax charges at him. Hector falls back and flings the armour into a chariot, to be taken back to Troy. Ajax now takes a position over Patroclus’ body.

Glaucus again mocks Hector. He addresses him in feminine terms, and warns him that his own Lycian forces will withdraw from Troy’s defence if Hector cannot show that he will protect his men. Glaucus is angered that Hector has abandoned the body of Sarpedon. He tells Hector that if the Trojans can drag Patroclus’ body back to their side, they will be able to use it to bargain for the return of Sarpedon. He again implies Hector is a coward for avoiding a fight with Ajax. Hector says Glaucus is insolent and invites him to watch him battle Ajax. He calls to his men for support and declares he will wear Achilles armour. But to do this he must turn away from the battle and head a little way back to Troy to catch the chariot which bears Achilles’ armour. He stops it and changes into Achilles’ armour. Zeus, who sees this, pities Hector, who is unaware that his own death is also near. He decides to grant Hector great power in compensation, saying to himself that Hector will never again return home from battle. Zeus imbues Hector with power and makes Achilles’ armour fit him well. Hector now goes back among his troops, inspiring them. He makes a speech to his troops which seems to be a response to Glaucus’ criticisms. He says he never sought military support except to help defend Troy while he fought the war: that the Trojans could win on their own. He even suggests that the extra forces at Troy only cost him food. So now, he says, he asks something in return. That they all attack to take Patroclus’ body, and he will give half the spoils to any man who can take it.

When Ajax see Hector’s fighting force bearing down on them, he tells Menelaus to call for reinforcements. He is not confident they can withstand them. Menelaus calls for his captains to lead their troops forward. Meanwhile, Menelaus and Ajax stand in a ring with their troops around the body as the Trojan attack hits them. At this instant, Zeus spreads a deep, dense mist over the battlefield. The Trojans push the Argives back and begin to drag Patroclus’ body away. Hippothous, who is hoping to gain fame, drags the body away, but he is killed by Ajax with a spear to the head. Hector hurls a spear at Menelaus but misses and hits Schedius, instead. Ajax then attacks Phorcys who is trying to protect Hippothous’ body.

The Trojans are again demoralised. They wish to return to the city. But Apollo appears to Aeneas as Periphas, who had been his father’s herald. He upbraids Aeneas for the demoralised state of the Trojans who still have Zeus on their side. Aeneas, in turn, upbraids Hector for allowing the troops to return to Troy. He urges Hector to not allow the Argives to return to the ships with Patroclus’ body without a fight. Aeneas now makes a stand and other Trojans turn to support him. He kills Leocritus. Lycomedes, seeing the kill, strikes at Hippasus, and kills him. Menelaus rallies the troops tightly around Patroclus’ body and commands them to hold their position, without any attempts to strike out and break formation. The battle rages on.

Despite all this, Antilochus and Thrasymedes have still not heard that Patroclus is dead.

The battle rages most of the day. Homer describes it as a tug-o-war, or like the stretching of a bull’s hide in a tannery, as the corpse is dragged first one way and then back the other way through the course of the fighting.

As all this happens, Achilles is also not aware of the death of his friend as he sits back at the ships, nor does he ever think it a possibility.

As the battle rages, soldiers on each side call not to allow the body to be taken, as a matter of honour and glory.

Achilles’ horses, which have remained strapped to his chariot, weep for the loss of Patroclus. The horses are so overcome with emotion, they will not move. For the second time, Zeus takes pity. He resolves that Hector will never ride behind them, and decides to give them strength and resolve to take Automedon from the battle in safety. As they feel the effects of Zeus’ support, the horses gallop off, taking Automedon with them. However, the horses charge the wrong way, at the Trojans, and Automedon tries to fight from the chariot, but the movement of the horses is too fast and haphazard. Alcimedon sees what is happening and calls to Automedon that he has gone mad. Automedon calls for Alcimedon, a better chariot driver, to leap onto the chariot so he can leap off and fight the Trojans. Hector, seeing this, asks Aeneas to help him target the chariot and horses. Meanwhile, Automedon fights the Trojans and perceives the Trojan plan to take the horses. He calls to Alcimedon to stay as close as he can. He then calls to the two Ajaxes and Menelaus to leave the defence of Patroclus’ body with other men, and to help him to defend against the attack of Aeneas and Hector. Automedon kills Aretus. Hector throws a spear at Automedon but misses. The two Ajaxes push back the Trojan forces and Automedon strips Aretus of his armour and tosses it into the chariot.

Zeus again interferes. He sends a freezing blizzard into the battle. But Athena uses this for cover, first to speak to Menelaus and then other Argive troops in the form of Phoenix. She spurs them on to fight. Menelaus says he wishes Athena would give him and his men the power to drive the Trojans back, but laments that Zeus is against them. Athena answers Menelaus’ prayer and fills him with courage. He again stands over Patroclus and flings a spear, killing Podes, a close friend of Hector’s. On his side, Apollo stands by Hector disguised as Phaenops, and urges Hector to action, asking what Achaean would now fear him, otherwise?

At this moment, Zeus sends a lightning bolt that emboldens the Trojans and sends fear into the Argive forces. They begin to break formation. Peneleos is wounded when he charges forward. Hector wounds Leitus. But Idomeneus spears Hector, but his armour deflects the blow. Hector returns a spear at Idomeneus but misses, and kills Coeranius, Meriones’ driver, instead. Meriones urges Menelaus to flee to the ships. Fear seizes Idomeneus, and he flees to the ships in his chariot.

Menelaus and Ajax see that Zeus has turned the tide of the battle again. Ajax is frustrated by this, realising that retreat might be their only option. He still hopes to retrieve Patroclus’ body and win something from the day. But he decides the best course would be to send a messenger to Achilles to report the news of Patroclus’ death. He then prays to Zeus to lift the mist to let them properly see the battlefield. Zeus again feels, pity, and he removes the mist. Ajax tells Menelaus to send Antilochus as a messenger to Achilles.

Meanwhile, Ajax fights a desperate action over the body of Patroclus. He is described as a lion being driven from its kill by the many harrying hounds who have worn it down. Wearied, he is forced to leave the body, hoping that his men will not lose heart and abandon it, too.

Menelaus discovers Antilochus is still alive and orders him to return to the ships to tell Achilles what has happened. He hopes that Achilles might be able to retrieve the body from the Trojans if he is fast. Antilochus leaves with the message, weeping freely over what has happened. He has only just found out Patroclus is dead. Menelaus is not hopeful Achilles will come. As a practical matter, he now has no armour. With this possibility, Greater Ajax tells Menelaus and Meriones to shoulder the body, and he and the other Ajax will fight a rearguard action to protect them. The Trojans attack as Patroclus’ body is lifted. They are described as dogs harrying a wounded boar, relentless in their pursuit, except when the Ajaxes turn on them directly. The Ajaxes are described as two men beating back a flood or killer tides, while Hector and Aeneas pursue relentlessly as the Argive forces make their way back to the beach.

The animal imagery used in the past few books is continued in this book by the narrative voice. Menelaus is a devouring lion, and other Greek fighters are compared to lions or powerful boars, while the Trojan forces are typically compared to hounds that work as a pack, never quite capable of taking down their noble prey, but wearying them, nevertheless. This time, one example will do to reiterate the point:

The repetition achieves a cumulative impression: The Greeks are great and noble warriors who would be winning the war, but for the intervention of Zeus, who has promised Thetis, Achilles’ mother, that they will suffer on account of the insult to Achilles (See Book 16 for a more comprehensive explanation of this point). Hector is portrayed as a straw man, propped up by Zeus for these purposes, fighting beyond his capacity or real courage. The tide of the battle turns in favour of the Trojans at the whim of Zeus, who forbids the intervention of any other god. In short, Hector does not fare well if we read The Iliad closely, but we also understand that it is easy to read The Iliad as a piece of Greek propaganda. The imagery and circumstances make the Greeks the noble underdogs (underlions?) while the Trojans, particularly Hector, is diminished.

For a start, Hector’s actions would effectively turn the imagery of noble or powerful beasts on its head if he were successful. He attempts to remove Patroclus’ head, with the intention of feeding his body to Trojan dogs. In effect, Patroclus would be lower than hounds. He would be dog food.

But in addition to this, Hector again fails to show courage, and it is Glaucus who again calls him out, with some bestial imagery turned against the Argive forces:

But how this scene plays out is interesting. He demeans Hector with feminine insults. He refers to Hector as a “prince of beauty” and that his glory is not even a runner’s glory but “a scurrying girl’s”. Glaucus threatens to withdraw his Lycian forces from the battle if Hector cannot find the courage to face Ajax and win Patroclus’ body, so that they might trade it for Sarpedon’s. This is the second time Glaucus has openly criticised Hector over the death of Sarpedon and his failure to show leadership. He criticises him in Book 16 as well.

Now, however, we get a sense of the weakness of Hector’s position and his own lack of confidence. He is compelled to answer Glaucus’ criticisms. He shows contempt for Glaucus and says he is insolent. “You tell me that I can’t stand up to the monstrous Ajax?” he asks Glaucus rhetorically. He urges Glaucus:

This is a moment of reputational danger for Hector. He has to respond to Glaucus and do what he is clearly unwilling to do. Weirdly, he chases down the chariot heading back to Troy to don Achilles’ own armour first, and then, instead of heading into battle against Ajax, he chooses to return to his troops wearing the armour. As Hector returns to make this speech, Homer tells us that he was “inspiriting every captain” and that he drives his men on with “winging orders”. And indeed, he offers a handsome reward for any man who can retrieve Patroclus’ body from the battlefield by the end of his speech. But having been threatened by Glaucus that he will withdraw troops, his first thought is not to rouse his troops to fight, but to answer Glaucus’ criticisms publicly. Hector claims he can stand alone:

Hector’s words seem to reflect a noble sentiment – to protect women and children – but he also diminishes the importance of his allies with these remarks, and in the context of what has just happened, it is reasonable to assume these remarks are directed at Glaucus, specifically. Hector relegates the role of his allies to baby sitters: needed only to stay back with women to guard them. In the parlance of this period, it is somewhat insulting, but seems designed to dismiss Glaucus’ threat, and his feminine insults aimed personally at Hector. But Hector presses further:

It is unclear to whom he directly speaks here, even though it is clear he is about to demand a quid pro quo for the cost of supporting the troops at his command (support for retrieving Patroclus). But if these remarks are again a slight against Glaucus, then he suggests Glaucus is costing him more than he is worth. Moreover, that Glaucus lacks courage.

In the end, the scene makes Hector seem a little petty. And it also distracts from the fact that Hector does not challenge Ajax directly in this book, despite what he tells Glaucus he will do.

Hector does not fare well in his representation by Homer, but we have to also understand that Homer, for the most part, seems to be on the side of the Greeks.

While artists representations of Book 16 of The Iliad mainly focus on the death of Sarpedon, by Book 17 artists address the scene of Patroclus’ body being defended or removed from the battlefield.

This wonderful etching from the 16th century is a real curiosity in relation to the actual text of Homer, since it bears little relationship with the story. We know that Patroclus set out disguised as Achilles to help drive the Trojans away from the ships. But Patroclus oversteps his remit, and pushes on towards Troy against the directions of Achilles. That is the first curious thing about this image. The battle seems to take place in a mountainous region, far from the city. Troy sits on the coast in the distance, below. This is compositionally pleasing, but entirely wrong. The other fascination is the confusing nature of the battle taking place. The men in the plumed helmets riding horses have the upper hand. Putting aside the fact that Homer has horses pulling chariots, not being ridden, the status of the man holding the body of Patroclus in the centre of the image is somewhat ambiguous. He wears the same crested helmet as those on horses, but his stance and facial expression suggests a man who is vulnerable, with something to fear. Whereas, those without plumed helmets are clearly defeated and present no credible resistance. Again, this does not mesh with the events of Book 17. By the end of the book the Greek forces manage to remove Patroclus, but they are harried the entire way as Hector’s forces pursue them.

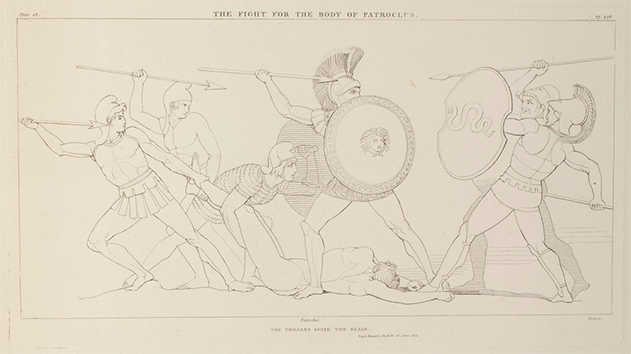

John Flaxman, a British sculptor, was commissioned to produce illustrations for The Iliad and The Odyssey with the intention that they would be engraved and published. Flaxman produced line drawings without colour that became highly popular in the 19th century. Tommaso Piroli made engravings from the drawings, and the result of one such interpretation from drawing to engraving can be seen here. Flaxman’s stylised stances are captured faithfully by Piroli, who completes the image by filling in details of the unfinished drawing and adding another figure on the right. The drawing reflects Flaxman’s influence by the formalism of Classical sculpture, but also faithfully capture the scene as the right to Patroclus’s body is contested.

This sculpture is a Roman copy of a 3rd century Greek sculpture. Its representation is uncertain because it is thought to be Menelaus carrying Patroclus, but it might also be Ajax carrying the body of Achilles, or possibly Odysseus. This sculpture is a part of a group of sculptures now known as The Pasquino Group (named after a shop where the statues were found) and there are as many as fifteen copies of it from Roman times. As a representation of Menelaus and Patroclus, it is somewhat strange. Menelaus would seem to be personally moved by Patroclus’ death, which is not what we might expect. However, this is supported in lines from the opening of Book 17:

It is difficult to know whether this relief sculpture is meant to represent a scene from Book 17 of The Iliad, or whether it represents a scene later on. The reason to doubt it comes from the static nature of the image. Patroclus is lifted onto a chariot while others watch. The moment is respectful, and is imbued with the kind of reverence only possible without a battle underway. Instead, the scene in the last lines of Book 17 is one of desperate flight and rearguard action.

That Menelaus and Meriones are the two soldiers lifting Patroclus’ body in this relief makes it somewhat likely that the scene is meant to commemorate the final moments when Patroclus is taken from the field of battle. Of course, that is if the identification is accurate. Greater Ajax instructs “Lord Menelaus. Quickly, you and Meriones shoulder up the body, carry it off the lines.” Of course, the figures in the relief sculpture have probably been identified as Menelaus and Meriones on the basis of these lines from Homer.

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!