This book picks up the action from lines 457-475 of Book 15, which is a short aside in the action in which Patroclus decides he must try to persuade Achilles to join the battle to defend the ships against the Trojan onslaught.

As this book begins Patroclus reaches Achilles and cries. Achilles compares him to a little girl and taunts Patroclus. Patroclus tells Achilles that their best champions are wounded and mostly out of action. He criticises Achilles’ intractability and says his skills are of little use if he does not help defend the ships. But he thinks Achilles may be bound to other principles or prophecies he may not understand, so he suggests that he take the Myrmidons into battle, himself, in Achilles’ place. He asks to wear Achilles’ armour so that he might be mistaken for Achilles on the battlefield. Given that the Myrmidons are fresh troops, they could make all the difference. Achilles rejects the notion that he is held back by a prophecy, and reasserts that it is only the insult he suffers to his honour from Agamemnon, who took Briseis from him and stoked his anger, that keeps him from the battle. He says that even he cannot be angry forever and that his intransigence now rests on principle: that he said he wouldn’t fight unless the battle reached his own ships. But he is nevertheless attracted to the idea of the Trojans quaking in terror when they see his own helmet in the battle: how it would panic them. He imagines there is no one left capable of turning the battle like he could. So, he agrees to Patroclus’ plan, that Patroclus will lead the Myrmidons in his stead. He imagines the honour Patroclus will win for him, and that Briseis will be sent back to him as a result. But he sets a limit on Patroclus. He says that once the ships are saved Patroclus must not push on to the city of Troy, but return to him. At this point he says he is concerned lest a god then join the battle and put Patroclus in danger.

Meanwhile, out at the battle, Ajax is no longer able to continue his defence from the deck of the ships. He is being overwhelmed and is physically tiring. Hector attacks Ajax and breaks the long pike he has been using to conduct battle from the ship decks. Ajax falls back and the Trojans finally set one of the Greek ships alight. When Achilles sees this, he urges Patroclus to head to battle. Patroclus puts on Achilles armour and takes his weapons, except his spear which was a gift from his father. Automedon readies Achilles’ chariot with his four war horses, Roan Beauty, Dapple, Lightfoot and Bold Dancer. As the Myrmidons are readied for battle Homer likens them to hungry wolves. They rally around Patroclus. Homer describes Achilles’ force. They came to Troy in fifty ships, each ship carrying fifty fighters, so Achilles’ fighting force is about 2500 men. Their captains are Menesthius, Eudorus, Pisander, Phoenix and Alcimedon. When the forces are mustered Achilles reminds his men how they all resented him when he pulled them from the fighting. He points out that they now have an opportunity to prove themselves. Automedon and Patroclus lead the men out in Achilles’ chariot.

Achilles returns to his shelter where he opens a sea chest in which he has stored a “handsome, well-wrought cup”. He uses the cup to offer a libation to Zeus, and sends up a prayer, asking Zeus to fill Patroclus’ heart with courage, to allow him to repel the Trojans from the ships, and then to return safely to Achilles. Zeus hears the prayer. He is willing to allow the ships to be saved, but he will not allow Patroclus to return.

The Myrimidons join the battle and instantly begin to turn the tide against the Trojans. Patroclus urges his troops forward for Achilles’ honour. The Trojans panic, thinking that Achilles is leading the Myrimidons against them. Patroclus makes the first kill. He hurls his spear and kills Pyraechmes. Pyraechmes’ Paeonian force panics when they see their leader killed and they are driven off. Protesilaus’ ship, which was the ship Achilles saw set alight, is half burned but still upright. Zeus sends a storm to the beach and the ship’s fire is quenched and the ships are saved.

What follows is another sequence of killings, typical of Homeric battles. Patroclus kills Areilycus, Meges turns the tables of Amphiclus, and Nestor’s son, Antilochus, kills Atymnius. Maris attacks Antilochus, wishing to protect the corpse of Atymnius, his brother, but Thrasymedes kills him too before Antilochus has a chance to respond to the attack. Oilean Ajax kills Cleobus, Peneleos fights Lycon and beheads him. Meriones runs Acamus runs down Acamus with his chariot, Idomeseus skewers Erymas through the mouth with his spear. Great Ajax targets Hector, but Hector knows the tide of battle has turned. Hector stands helping to defend his men, but the fighting becomes too intense and he speeds away in his chariot. Many other Trojan chariots become trapped in the Greek defensive trench and chaos ensues. Patroclus calls on the Greek forces to slaughter them. As the Trojan chariots begin to break for Troy, Patroclus places himself in their way. He tries to stop Hector but Hector dodges him. But he kills others. He kills Pronous and then he attacks Threstor who is cowering in his chariot. He stabs Threstor beneath the jaw with his spear and flips him over his chariot, like an angler tossing a fish ashore. Homer lists a number of men Patroclus kills next and describes them as “a blur of kills.”

Sarpedon, the son of Zeus who leads the Lycian forces, rallies his troops. He then leads by example. He leaps from his chariot to confront Patroclus. Patroclus leaves his chariot, too, to confront him. Zeus watches on, in grief over the fate he knows his son now faces and wishing to save him. But Hera warns Zeus that if he interferes, he will be setting a dangerous precedent that will encourage all the gods to interfere in human affairs for the sake of their offspring. She advises him to allow Sarpedon to die, then have him taken from the battlefield, his body prepared and returned to Lycia for burial. Zeus concedes the wisdom of Hera’s advice and agrees not to interfere.

Back on the field of battle Patroclus targets Sarpedon’s chariot drive, Thrasymelus, and kills him. Sarpedon throws his spear but misses Patroclus and kills the horse, Bold Dancer, instead. Automedon cuts the dead horse free of the harness. Sarpedon throws another spear but misses entirely. Patroclus throws another spear and this time hits Sarpedon in the heart. Sarpedon, dying, calls to his comrade, Glaucus, asking him to rally the Lycian captains and protect his body from being plundered. He dies. Patroclus pulls out the spear, along with part of his midriff. Glaucus, wishing to honour Sarpedon, is hampered by his own wounds. He has been shot by one of Teucer’s arrows. He prays to the god, Apollo, to heal his wound so he can rally the Lycian troops and protect Sarpedon. Apollo grants his request. Glaucus then urges the captains on. When he finds Hector and Aeneus he criticises Hector. He accuses him of abandoning his allies and demands he help defend Sarpedon. Sarpedon is well loved in Troy, even though he is not Trojan, and his death inspires grief among the men. The Trojans now renew their attack against the Greek force, and the Greeks, in turn, rally around Patroclus. Patroclus expresses a desire to Ajax to seize Sarpedon’s body and mutilate it. The two armies clash around Sarpedon’s body, but Zeus intervenes and brings about an unnatural night. Hector now kills one of the Myrmidons, Epigeus, over the body of Sarpedon, smashing his skull with a rock. Angered by this, Patroclus surges through the battle, killing Sthenelaus with a rock on his way, and the Trojans give ground. But Glaucus kills Bathycles while Meriones kills the Trojan captain, Laogonus. Aenaes hurls a spear at Meriones but misses. Aenaes taunts him for his luck and Meriones taunts him back, saying what he could do to him with a lance. Patroclus upbraids Meriones for taunting the enemy when he could be fighting, instead The fighting continues and the field is a mass of weapons and confusion. Zeus encourages the fighting to continue as he considers what he might do with Patroclus: to have Hector kill him, or to allow him to continue with his onslaught, for now. He decides on the latter, so he inspires fear in Hector, who leaps on his chariot and calls for a retreat. The Trojans lose courage as Hector retreats, so the Achaeans have an opportunity to finally take Sarpedon’s armour as a prize.

Zeus orders Apollo to retrieve Sarpedon and carry out the plan to return Sarpedon to Lycia as Hera suggested.

Meanwhile, Patroclus begins to overstep himself. He forgets Achilles’ orders, and continues to slaughter Trojans after the ships have been saved. Having already done his part for Sarpedon, Apollo has returned and takes a stand to defend the walls of Troy. Patroclus attacks three times and is repelled three times. On his fourth attempt Apollo tells him to go back; that it is not his fate to take the city. As this is happening, Hector is at the Scaean Gate, wondering if he should return to the battle or move his troops into the city. Apollo appears before Hector as an old fighter, Asius, and encourages him to rejoin the battle, adding that he might kill all the Greeks if he does. Hector orders his driver, Cebriones, to ready the horses to return to battle. As he drives back into the battle, he ignores all the Greek forces. His target is Patroclus. Patroclus sees the attack and throws a rock. He misses Hector but hits Cebriones between the eyes. It crushes his skull. Cebriones falls from the chariot. Patroclus mocks his corpse and then leaps down to it, recklessly putting himself in danger. Hector leaps from his chariot and the two men tussle over Cebriones corpse, Hector with the head, Patroclus with the feet, like a weird tug-o-war. The battle now gathers around Cebriones’ corpse. The battle continues into the late afternoon until the Greeks mount a fiercer attack and manage to drag Cebriones’ body free of the melee and strip its armour. Patroclus continues his attacks and kills another nine men.

But Apollo looms up behind Patroclus and knocks the helmet from his head. Hector gets the helmet. Patroclus’ spear is shattered in his hand and the shield is stripped from his shoulders by the god, along with his breastplate. A Dardan soldier, Euphorbus, spears Patroclus, removes the spear and disappears into the ranks, not willing to fight him, as defenceless and wounded as he is. Hector, seeing the situation, rushes at Patroclus and stabs him through with his own spear. Hector mocks Patroclus as he dies for his presumption that he might have stormed the city, and wrongly supposes that Achilles orders were not to return until Patroclus had killed him. Patroclus answers Hector by diminishing his victory. Patroclus tells him that twenty Hectors could not have beaten him without the aid of Apollo, and he only delivered the killing blow after Apollo and Euphorbus had first attacked him. He predicts Hector will soon die, too, claiming he sees death and fate looming like ghosts beside him. Patroclus dies but Hector has to have the last word, suggesting it might be him who kills Achilles. He pulls the spear from Patroclus and attempts to attack Automedon with it, but Automedon is taken to safety by Achilles’ fast horses.

In Book 15 Hector was propped up by Zeus after he was badly injured by a large rock thrown by Ajax. In that book we get the impression that Hector’s ‘greatness’ is a result of Zeus’ support, and that given Zeus’ support is predicated merely on a promise he made Thetis, Achilles mother, this does not bode well for Hector.

In this book this impression of Hector remains. He may be remembered in popular culture as an iconic hero or warrior, but his deeds seem even less heroic now, especially his killing of Patroclus. In Book 16 Homer continues the use of bestial imagery and imagery connected with natural events like storms, wind and floods to describe the actions of fighters and the curse of the battle. However, until the scene in which Hector kills Patroclus, this imagery is used to convey a sense of power to Patroclus or the Myrmidons he leads almost exclusively. Homer is using it to convey the sense of their power and their significance to the battle. Here, the Myrmidons are compared to hungry wolves as they anticipate battle:

The ferociousness of their attack is compared to a swarm of wasps, in contrast to the Trojans who are merely foolish young boys who have been foolish enough to poke the nest:

The Myrmidons are often compared to hunting animals like lions or wolves, while the Trojan forces are likened to herd animals, like cattle or sheep, defenceless against their attackers. The following example illustrate this:

Patroclus is also portrayed as a wild animal of one sort or another. When Epigeus is killed, Patroclus is incensed, and Homer’s imagery of Patroclus as a hawk serves to convey the ferocious speed with which he moves:

When Homer describes the clash between Patroclus and Sarpedon he applies bestial imagery to them equally. Each fighter is a vulture, fighting viciously with hooked-claws:

Homer returns to the imagery of the lion to apply it to Patroclus specifically when he describes Sarpedon’s death scene:

And Homer associates both Patroclus and Hector as lions fighting over a kill as they each try to physically wrest the corpse from each other:

But the power conveyed by Homer’s use of animal imagery has mostly favoured Patroclus and the Myrmidons throughout this book. That changes during Patroclus’ death scene. Now, it is Hector who is exclusively the lion, while Patroclus is the wild boar who will inevitably be defeated:

As in Book 16, Homer uses imagery from nature, and like his use of bestial imagery, it is mainly used to convey the power of the Greek forces, or the weak position of the Trojans. In this example the Greek forces are a storm cloud that sweep the Trojan forces before them:

In describing the desperate retreat of Hector and the Trojans, Homer imagines them as a flash flood created by the rains of Zeus, implacably rushing downhill to the sea, with nothing to stop it.

The continued associations of powerful imagery with Patroclus, the Myrmidons and other Greek forces in this book creates a sense that the tide of battle has turned, and we are told several times that Hector believes this to be the case, too. However, Patroclus seems not only fated to die, as does Sarpedon – Zeus anticipates or foreshadows both their deaths – but we see him contribute to the circumstances of his own death by pushing on to the walls of Troy, trying to breach them. His actions anger Apollo, and it is this, not Hector, who is instrumental in Patroclus’ death. As he lays dying, Patroclus diminishes Hector’s victory: “deadly fate in league with Apollo killed me” [line 993] he says. It is true. Apollo has surprised Patroclus from behind, removing his armour, shield and weapons, and leaving him helpless. Even then, it is another man, Euphorbus, who strikes the first blow at an already helpless Patroclus, then flees back into the Trojan ranks, afraid to face Patroclus even in his diminished state. It is an act of cowardice that serves to reflect on Hector’s delivery of the coup de grace:

In numerous instances in this book we are given a sense of Hector’s cowardice. Glaucus criticises him for not supporting allies. Zeus instils fear in him and his men lose hope when they see Hector flee the battle. Hector loses hope quickly when the battle becomes difficult and he is often in retreat. Now we see him take glory for himself by killing an unarmed man who is already wounded, and then gloating over his victory:

Hector waits and watches until the matter of Patroclus fate is settled before swooping in to take the glory of it. It doesn’t feel heroic. For example, in Wolfgang Petersen’s 2004 film, Troy, starring Brad Pitt as Achilles and Eric Bana as Hector, Hector and Patroclus square up to each other with their armies surrounding them to watch. It is a straight one on one fight. Hector is the greater warrior in the film and Patroclus dies. But that’s not how it happens in Homer. Like other heroes in Homer – Achilles, for instance, is like a petulant child sometimes in his stalwart refusal to fight even when the ships are under threat – Hector does not feel as grand or heroic as we popularly remember him in our culture.

Patroclus’ death is the climatic moment of Book 16, yet the actual moment of his death is not represented in art so much as the fight for his body which takes place in the next book, when Menelaus, Ajax and the Greek forces defend it from the Trojan attempts to remove to Troy.

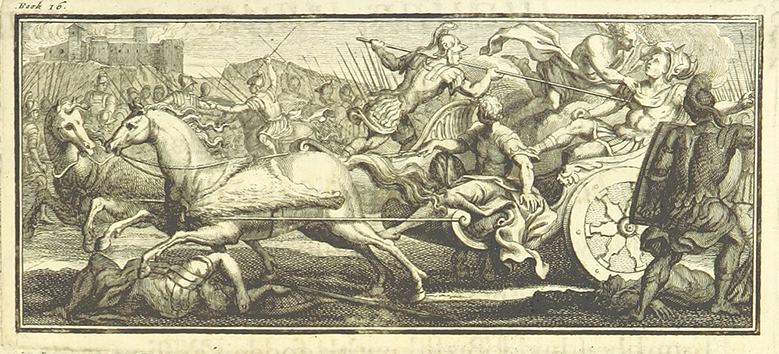

Art for Book 16 seems to mainly represent the death of Sarpedon, Zeus’ son, who is defeated by Patroclus. However, this first image is an engraving produced for the famous translation made by Alexander Pope in 1715 which is meant to represent the moment Patroclus is killed by Hector:

This is a curious image, given the detail from Homer. Hector and Patroclus are in their chariots, here, although in Homer, they have abandoned them by this stage. Hector’s chariot is mostly hidden in this image, so he appears to loom over the battle with superhuman will to spear Patroclus, who seems stunned and helpless. Apollo floats above Patroclus, removing his helmet at the same moment that Hector strikes. So there is no sense in this image that Patroclus has been progressively disabled by Apollo and Euphorbus before Hector comes in for the kill.

The following are representations of the death of Sarpedon and the treatment of his body:

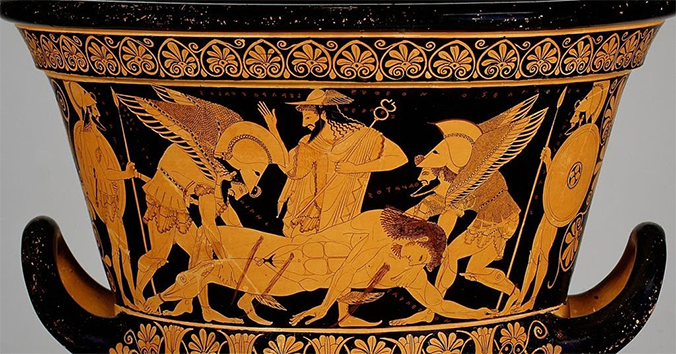

This Krator, also known as the Euphronius Krator, after its artist, depicts the removal of Sarpedon’s body from the field of battle by Thanatos (Death) and Hypnos (Sleep). Hermes stands behind them, supervising. All three figures are identified in writing on the krator, itself. Sarpedon’s wounds still bleed.

This slightly later amphora jar depicts the same scene as the Sarpedon Krator. However, the figures are achieved using the black-figure technique, in which material from the surface, fired to a black finish, was removed to reveal the natural colour of the clay beneath, leaving black figures on a light background. This is the opposite of the Sarpedon Krator which uses the red figure technique, where the background is painted black, leaving the figures in the scene in the colour of the natural clay. I personally think the Sarpedon Krator is more elegant with its fine lines and details. The effect here is a simpler composition of almost the same scene.

Details of the scene, however, are different. Sarpedon bleeds from his wounds, as in the Sarpedon Krator, but his body is carried flat, rather than at an angle, so the details of his body are not as apparent and some of the pathos of the scene is lost. His face is almost hidden from us.

While the figures carrying Sarpedon’s body are usually identified as Thanatos and Hypnos, they are not represented as divine beings, here. Significant differences lie in the appearance. The figures have no wings, unlike Thanatos and Hypnos in the Sarpedon Krator, and their helmets are not as ornamental. Instead, they are represented as ordinary soldiers. They wear chiton, corselet, greaves, and bear spears.

Another difference lies in the figure in the middle of the scene. In the Sarpedon Krator the figure is Hermes, as identified on the piece, itself. Here, the figure represents Sarpedon’s soul, or psyche, leaving his body after death. In essence, they appear to be ordinary soldiers and Sarpedon’s death is like many soldiers who die in the battle. The Diosphos Painter has portrayed the same moment as Euphonius, but the supernatural elements of the scene, apart from the escaping soul, have been replaced by a more realistic but less elegant representation of Sarpedon’s death

This Etruscan piece portrays a similar scene to the previous two works of art. Given that it is much later, it is quite possible it was influenced by the Euphronius Krator, since the pose of the figures and even the way Sarpedon’s body is carried, side-on, seem identical. What is missing is the central figure, Hermes, which makes sense because this piece is a cista handle, meant as a practical ornament to a box, a cistae, which was used to store cosmetics or other precious items.

The following two paintings are extremely different in their colour pallet, but their subject is treated in a very similar manner. Sarpedon is removed from the battle, ready to ascend towards heaven.

In this first painting Apollo directs Hypnos and Thanatos to remove the body of Sarpedon. The coours are vibrant and there is a strange eroticism that is suggested. Neither Hypnos nor Thanatos were women, but one of them, presumably Hypnos, is represented as a woman here. She is beneath the corpse of Sarpedon with flowers in her hair, while Sarpedon lays, a wound in his side and his arms spread, recalling the wound of Christ and his posture in many paintings that depict him being removed from the cross.

Henri-Léopold Lévy’s image is more sombre, both in its colour pallet and its representation. The colours are muted and the scene more ethereal. Sarpedon’s body is lifted by Thanatos and Hypnos and is suspended midair, just before he is taken up by his father, Zeus.

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!