In this book Zeus regains control of the battle. But he also foreshadows his real intent: to secure revenge for Thetis against the Greek forces for the snub to her son, Achilles, and then to turn the tide of the battle against the Trojans.

This book begins as Zeus awakes from his induced sleep and finds the Trojans fleeing the battle and Hector coughing up blood from the force of a rock Great Ajax has hit him with in the previous book. Zeus is angry with Hera whom he suspects is behind this rout. He reminds her of terrible punishments he has inflicted upon her in the past for interfering with his son, Heracles. Hera is frightened by Zeus’ manner, so she lies, denying any responsibility for Zeus’ induced sleep and the consequences of that for the battle, or Poseidon’s interference. In order that Hera may prove her loyalty, Zeus demands she summon Iris for him, so that Iris may deliver a message to Poseidon, and Apollo so that Apollo can aid the Trojans. At this point Zeus delivers the first foreshadowing of his intentions in this book. He says he intends that Patroclus will enter the battle and slaughter many Trojan fighters, including Zeus’ own son, Sarpedon. Once Patroclus dies, Achilles will fight again and kill Hector. At that point, Zeus intends to turn the battle in favour of the Greek forces. He is adamant that he will never relent in his punishment of the Greeks until Achilles prayer is answered and he has fulfilled his debt of gratitude to Achilles’ mother, Thetis.

Hera obeys Zeus’ will and flies back to Olympus where she is greeted by Themis, who sees there is something wrong and realises Hera has been terrified by Zeus. Hera is reluctant to speak of what has happened, but she warns the other gods not to oppose Zeus. She characterises any resistance as pointless effort which only brings suffering. She tells Ares of the death of his son, Ascalaphus, who was killed by Deiphobus with a misaimed spear thrust in Book 13. Ares is enraged and vows revenge. He calls on his henchmen, Rout and Terror, to prepare for battle, but Athena intervenes. She tears Ares helmet, shield and spear from him and angrily chides Ares for preparing for war against the warnings made by Hera. She warns that Ares will bring Zeus’ wrath upon them all if he goes down to Troy for revenge.

Hera summons Apollo and Iris. She instructs them to go to Mount Ida where Zeus resides and to follow his instructions. They go. Zeus commands Iris to relay a message to Poseidon, that he should leave the battle and go back to the sea: that he has not the strength to stand against Zeus. Iris relays this message to Poseidon. Poseidon is affronted. He speaks of his coequal power, shared with Hades, who controls the underworld, and Zeus who controls the heavens. Poseidon argues that on the earth, itself, they all are equal. He refuses to obey. Iris urges him to be more moderate. Poseidon relents and tells Iris he will back down, but warns that if Troy is not defeated there will be an eternal breach between himself and Zeus. Poseidon enters the ocean and leaves the battle.

Zeus commands Apollo to go to Hector. He wants Apollo to turn the tide of battle against the Greek forces again. He again foreshadows his plans. He intends to give the Argive forces a reprieve once they are forced back to their ships. Apollo goes to Hector who is still feeling the effects of Ajax’s rock. Apollo urges Hector to rejoin the battle. He promises Hector that he will pave the way for him in battle and force the Argives back. So, Hector rejoins the battle with Apollo’s support and the Argive’s again lose courage and try to flee. But Thaos son of Andraemon, perceives that Hector has been saved by the gods, and tells the Greek troops that Hector only bests them with the gods’ help. He tells the ordinary fighters to fall back to the ships, but encourages the best warriors to attack Hector with him. Thaos is joined by Great Ajax, King Idomeneus, Teucer, Meriones and Meges.

The Trojans, led by Apollo, press forward. The Argive champions stand their ground while ever Apollo’s eyes are behind his shield, but when he looks them eye to eye, they lose their courage. Homer describes their forces as being like herds of cattle or sheep fleeing the stampeding of wild beasts. Now the Trojans have the best of the battle. Hector kills Stichius. Aeneas kills Medon. The Greek champions flee back through the trench towards the ships and Hector urges his men to follow. Apollo leads the Trojan forces on. He kicks an enormous amount of earth into the trench, effectively making a bridge for the Trojan forces to cross, and then tears down the Argive rampart. Nestor, who sees the danger, prays to Zeus to save them. Naturally, this is not Zeus’ plan right now, so all he does is let loose a crack of thunder, which only emboldens the Trojans further. As the Trojans storm over the rampart the Greeks are forced to fight from the decks of their ships with long pikes designed for naval engagements.

During all this Patroclus is sitting with a friend, Eurypylus. Patroclus’ instinct is to try to persuade Achilles to fight, or at least go out and fight, himself.

Now that the battle is at the ships the odds become more even, with neither side gaining an advantage. Ajax and Hector fight each other, but their fight remains inconclusive. When Caletor, a Trojan, is killed, Hector calls for his fighters to protect his body so that his armour is not stripped. Hector throws a spear at Ajax but hits Lycophron, instead. Ajax calls for the aid of the archer, Teucer, to get revenge against Hector for Lycophron’s death. Teucer sends arrows into the Trojan ranks and kills Clitus in his chariot. But when he aims at Hector, Zeus causes the string on Teucer’s bow to snap. Ajax encourages Teucer to fight with a spear, instead. Teucer joins Ajax at his side. But Hector has seen Teucer’s bow string snap and perceives Zeus’ hand in this. Emboldened, he again calls for his men to make for the ships, saying that the gods are on their side, and that they should fight for glory. Ajax hears Hector’s rallying cry, so he calls to his own men to fight for the ships and not to allow an inferior force to defeat them.

There is a spate of deaths now. Hector kills Schedius and Polydamus kills Cyllenian Otus, Meges’ friend. Meges attacks Polydamus but Apollo protects him. Meges’ blow hits Croesmus instead . Meges begins to remove Croesmus’ armour, but the Trojan, Dolops, attacks him. Meges delivers a mighty blow to Dolops’ head, but his helmet saves him. It splits and falls to the ground. But Menelaus intervenes in this fight and spears Dolops through the shoulder and kills him. Hector calls for Melanippus, Dolops’ cousin, to protect Dolops’ body from being stripped of its armour and to strike the Greeks down.

Ajax urges the Greek forces to keep their discipline and protect the ships, while Menelaus taunts Antilochus, a young and speedy Greek soldier, to attack the Trojans, in the hope he will be slaughtered. Antilochus does attack, and kills Melanippus, but he is forced to flee when Hector and other Trojan soldiers focus their attack on him.

At this point the narrative gives us a third foreshadowing of Zeus’ intentions. We are told that he intends to allow the Trojans to set fire to the Greek ships. Once that happens, he feels he will be free of his obligation to Thetis (This, of course, differs from the scenario he first outlined concerning the death of Patroclus). Once that is done, his intention is to turn the tide of battle and to give the Argives victory.

Hector is on the attack against the ships and Zeus protects him. In yet another foreshadowing, we are told that Hector will soon die, anyway. Despite help, the Trojans have trouble breaching the Argive defences. But Hector personally attacks with great fury, like a force of nature. His fury is so great that he sets the Greek forces to panic, even though he kills only one man, Periphetes, who trips over his own shield as he attempts to retreat.

As the Argive forces fall further back among the ships, Nestor begs the fleeing Greeks to find their courage. He begs them to remember their honour and their reputations amongst their families and communities back home. This brings new courage to the men, while Athena removes the haze of battle from their eyes, a darkness sent from the gods. Ajax leaps upon the decks of the ships, wielding his pike. He moves from ship to ship with mighty leaps. Likewise, Hector presses forward with his men, with the power of Zeus behind him. By this stage the Argives are determined to stand their ground while every Trojan is bent upon torching the ships. Bloody hand-to-hand combat is focused around Protesilaus’ ship. Hector leaps up, grabs a ship’s stern and hangs from it as he battles the Greek forces. As he does so he urges his men to seize the ships. He also reflects that he feels vindicated against the Trojan elders who urged him to use caution and not to attack the ships. The situation is desperate for the Greek forces, now. Even Ajax is falling back. He fends Trojans off from the middle of a bridge set between ships. He calls to the Greeks, reminding them there is no-one to save them and no other place to fall back to. As he defends his small bridge, he kills twelve men who try to attack him, and this is how Book 15 of The Iliad ends.

Much of the plot of The Iliad depends on Zeus’ unwavering support of the Trojan forces against the will of many of the other gods, including his wife, Hera, and Poseidon, who both contrive to have Zeus put to sleep in Book 14 so that Poseidon can turn the battle in favour of the Greeks. In Book 15 of The Iliad Zeus awakes and takes measures so that all Hera and Poseidon achieved against the Trojans in the previous book can now be reversed.

However, while Zeus’ loyalty to the Trojans is steadfast it is also conditional. Book 15 foreshadows several plot points in the latter part of The Iliad: the death of Patroclus and Hector, as well as the ultimate victory of the Greek forces, all foreseen and intended by Zeus. Zeus’ alliance with the Trojans seems strange since he eventually intends that they will lose. The narrator in Book 15 tells us:

The narrator’s use of adjectives like “bitter” and “disastrous” are at odds with the zeal with which Zeus supports the Trojans. In this book we begin to get a real sense of how things are beginning to turn in the narrative, not through its plot, which has seen the fortunes of the Greek forces and Trojans see-saw back and forth over the course of the last few books, but through the insight we are afforded into Zeus’ mind. By the end of this book the Trojans again have the upper hand. But we also have several foreshadowings of the plot and Zeus’ intentions, which bode ill for the Trojans.

The source of this seeming ambivalence on Zeus’ part can be traced back to the first book of The Iliad, to the “bitter” and “disastrous” prayer of Thetis. Achilles, having been dishonoured by Agamemnon by the loss of Briseis, goes to his mother, Thetis, a sea nymph, and begs her to ask for Zeus’ help in paying Agamemnon back. Achilles is aware that Zeus has a moral debt to Thetis which he will want to repay:

True to her son, Thetis begs Zeus to help Achilles:

Zeus responds to Thetis’ supplication with a solemn vow to do her bidding, which, as we have seen, he feels will release him from his obligations to Thetis for her saving him. He makes his vow:

Zeus had been bound with chains by Hera, Poseiden and Athena for his infidelities and abuse of power, but Thetis had broken him free with the help of the hundred-handed giant, Briareus. This is the debt that binds Zeus to his promise, and drives the whole plot of The Iliad.

There is no doubt that in Book 15 Hector, backed by the god, Apollo, is an unstoppable force. He begins this book weakened and wounded by the boulder Ajax has struck him with in the chest. He lies incapacitated and vomiting blood. Seeing this, Zeus turns on Hera, angry at the part he knows she has played in the Trojans’ reversal of fortune. He makes her send him Iris and Apollo. He intends that Apollo will fight on the Trojans’ side but first, he tells Hera, he intends that Apollo will,

Zeus continues to tip the scales in the Trojans’ favour, and in the favour of Hector, in particular. While Hector is Achilles’ equivalent on the Trojan side in The Iliad, the favours he receives from Zeus diminishes his personal glory in our eyes and in the eyes of the Achaean who must repel him. We know, through a series of foretellings in this book, that Hector will be defeated the minute Zeus stops supporting him. He is a useful tool for Zeus to acquit himself of his debt to Thetis. This is an observation made by Thaos son of Andraemon as Hector leads an attack against the Achaeans which tests their resolve. Thaos says to his men:

Hector is portrayed as a valiant fighter, but also, implicitly, as a man who has passed the natural limit of his stamina. Thaos’ remarks shows that Hector is considered to be a man propped up by the gods, and for this the Greek forces can despise him. He is saved from Teucer’s arrow by Zeus, who breaks Teucer’s string, and there is an implicit recognition in Hector’s rallying cry that he understands the favour he is given: “I see with my own eyes / how Zeus has blocked their finest archer’s arrows” [Book 15, lines 568-569].

It’s useful to remember this when considering Homer’s portrayal of Hector later in the book as an unstoppable force of nature. First, Hector is compared to violent weather at sea: of waves bursting over a ship, gale-force winds and blinding spray [Book 15, lines 722-730], that send the Achaean forces into disarray, as though they were that ship. Following this, the imagery used to portray Hector is of a hunting animal, like a lion, harrying the Greek forces:

The end of this extract is telling. Hector’s practical effect on the battle is minimal – he kills only one man – but it is the supporting terror of Zeus that drives Hector’s foes before him. This kind of predatory imagery is repeated a little further on, as Hector’s onslaught is compared to an eagle:

While the imagery of the eagle is an impressive image for a warrior, there is also a common association between Zeus and eagles that would not have escaped Homer’s audience. Zeus turned himself into an eagle to catch Ganymede, a young man Zeus became enamoured with, and take him to Olympus. It was Zeus’ eagle, Aetos Dios, that tortured Prometheus by eating his liver each day, and along with Zeus’ thunderbolts, became a chief attribute of Zeus’ persona. While the association with the eagle again makes Hector look impressive, it also undermines him. Here, it seems apparent that Hector and the Trojans are merely puppets of Zeus’ will. It is Zeus’ mighty hand that thrusts Hector on and urges his soldiers to follow. Again, we are reminded of the power which supports Hector and without which, he would already be defeated.

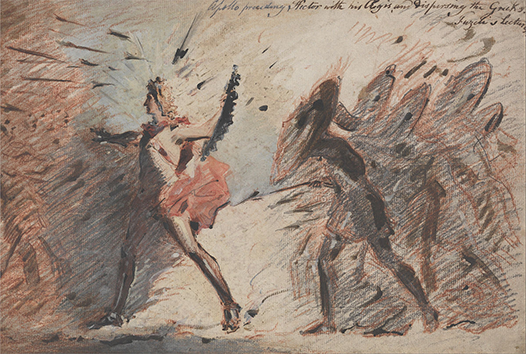

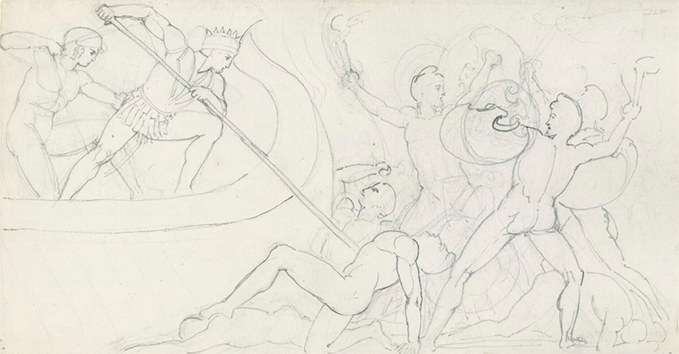

Book 15 of The Iliad continues actions that have spanned the course of several books by now – the defence of the ships – and so it is harder to find new art that is specific to this book. The two images below are from an eighteen-century artist, John Flaxman, who did a series of sketches to illustrate Homer’s work. Flaxman was commissioned to illustrate both The Iliad and The Odyssey. Flaxman began the drawing in 1792. He had a plan that the drawings would eventually be adapted into a series of bas-reliefs, although he never achieved this.

The drawings were first engraved and published in 1793, and were published two years later in London, as well. They were again published in 1805. The drawings were highly influential. If you search for Flaxman’s drawing of Ajax defending the ships, you will find many copies and imitations of his drawing.

This is a wonderful image of Apollo, arms stretched protectively outwards as the Trojans follow him into battle, hiding behind their shields. The Greek forces are to the left as well as out of frame. Apollo’s stance is fearless, regardless of arrows (it appears) which hurtle towards him, while the Trojans cower. This is an excellent image to consider in the light of my discussion about Hector and the support he and the Trojans receive from the gods. At this moment in the narrative, the Trojans maintain the upper hand, but we know from a series of foretellings that the Hector and the Trojans are doomed as soon as Zeus feels he is free of his obligation to Thetis.

There is a passage in Book 15 which is an apt accompaniment to this image:

This last image represents a specific scene of the battle as described in The Iliad. Homer describes how Ajax climbs aboard the deck of a ship as a defensive position. From here he uses a long pike normally reserved for naval engagements so that he might reach the Trojans below. In this image, Flaxman has chosen to represent Teucer beside Ajax with his bow. Teucer has played a role again in this book of The Iliad. He kills Clitus with an arrow when Ajax asks him to exact revenge for the death of Lycophron, so Teucer is associated with Ajax in Book 15. However, after Teucer kills Clitus he attempts to shoot Hector, but his bow string is broken by Zeus who is protecting Hector. Ajax encourages him to fight with a spear, instead.

This image represents a scene near the end of Book 15, after Teucer loses the use of his bow. In fact, Teucer does not appear beside Ajax’s side in this scene. Homer describes Ajax’s defence of the ships in the following passage:

However, despite the Greeks’ valiant defence of their ships the Trojans, with the help of the gods, are able to force them back further. By the end of this book even Ajax is forced to give ground:

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!