In this book the battle at the ships continues but the Greek forces fight back, and the limits of Hector’s skill as a leader are revealed.

This book opens directly after the moment the previous book ends, as the Trojans threaten to overcome the Greek defences at the ships. As this is achieved, Zeus’ attention is drawn to other matters in the world, and he turns his eyes from Troy, erroneously believing no other God will interfere in the conflict now. But Poseidon has witnessed Zeus’ withdrawal, and since he feels pity for the Greeks he strides down from Olympus and readies his battle-car and armour to support them. Poseidon travels from Aegea across the sea to Troy. When he arrives, he hobbles his horses in a sea cave. Poseidon emerges from the sea and speaks to the Argives in the voice of Calchas. He spurs Greater and Little Ajax to stand fast at the Greeks’ most vulnerable point in the battle. He strikes them with his staff and fills them with strength and courage. When Poseidon leaves, Little Ajax says that it was not Calchas who spoke to them, but a God. Both Greater and Little Ajax feel the courage and energy the god has imbued in them.

Poseidon continues to move through the Argive lines, spurring them on and shaming them into action. He expresses shame that the Trojans are now on the offensive at their own ships, and blames Agamemnon for his failure to end the feud with Achilles. Poseidon tells the men that they will make things worse if they hang back and do not take the offensive. The Achaeans close ranks and find their resolve. Now, the Trojan attacks are blunted against their lines. Hector’s personal attacks are likened to a boulder rolling down a hill until it hits a level plain. Because now when Hector attacks he makes no headway, but is repelled. Hector calls for his troops to rally about him to make another assault.

After this point, much of the rest of Book 13 is a recount of the battle, both in general terms as well as the specific encounters between heroes on the battle field.

First, the Trojan, Deiphobus, is encouraged by Hector’s words to step forward to take on the Greeks. The Greek, Meriones, throws a spear at him, but it breaks against Deiphobus’ shield. Meriones leaves the battle to return to the ships and retrieve his heavy lance.

Meanwhile, Teucer has the first kill at this point in the battle. He kills Imbrius. He tries to strip Imbrius of his gear, but Hector throws a spear at him. He misses Teucer but kills Amphimachus, instead. Hector now tries to strip the body of Amphimachus, but Ajax attacks and prevents him. Amphimachus’ body is retrieved and taken behind the Achaean lines. But the two Ajaxes fight fiercely and retrieve Imbrius’ body from the Trojans. They strip it of its armour, cut off the head and fling it back at Hector.

Poseidon, who has watched the battle, is enraged by the death of Amphimachus, who is his own grandson. He again surges through the Greek lines, spurring them on, and comes across Idomeneus, who has just seen to a wounded friend in the medical tents and is heading for his own tent. Poseidon talks to Idomeneus in the voice of Thoas, and asks him where the resolve to battle has gone that previous threats against the Trojans have implied. Poseidon, as Thoas, encourages Idomeneus to fight alongside him.

Poseidon leaves Idomeneus, despite his encouragement, and Idomeneus returns to his tent where he dons armour and gathers more spears. As he leaves, he bumps into Meriones, who is returning for his lance after breaking his spear against Deiphobus. Idomeneus offers Meriones any number of Trojan spears that he has retrieved from dead Trojans on the battlefield. Having been upbraided by Poseidon, himself, there is a feeling here that Idomeneus is subtly implying that Meriones is somewhat cowardly. Meriones says he also has Trojan spears, and that he has not forgotten his courage. Idomeneus changes his tone at this and says he knows Meriones is no coward; that cowards are easy to spot for their uneasy shuffling and the change in tone of the colour of their skin. He says Meriones would never receive wounds in the back. But he says they must return to the battle immediately, before someone else sees them talking and accuses them of cowardice. They stride back onto the battleground together, and consider where their presence would best serve the forces. They reason there are plenty of other great fighters in the middle line of the defensive line. The Argive left flank is the weakest point in its defence, so they decide to fight there. As they join the battle their presence raises the fierceness of the melee.

Poseidon surges from the surf again, eager for an Argive victory but again wearing a disguise because he does not wish to openly defy Zeus. The opposing intentions of each god involved in the war are merely raising the stakes for the mortals on the battlefield.

Idomeneus kills Othryoneus, who had been promised the hand of Priam’s daughter, Cassandra, in marriage. He pierces Othryoneus with his spear through the bowels, and then he mocks him as he dies, suggesting that he can marry Agamemnon’s daughter, instead, if he joins now with the Greeks. Idomeneus then tries to drag Othryoneus’ body back through the lines, but he is challenged by Asius, who tries to spear him. Asius’ charioteer, who becomes confused and frightened by Asius’ death, is also killed by Antilochus, Nestor’s son, who spears him, too. Deiphobus, upset at Asius’ death, tries to spear Idomeneus but misses and kills Hypsenor, instead. Deiphobus sees this as some level of revenge. Hypsenor’s body is retrieved and carried behind Greek lines. Idomeneus continues on his rampage. He next kills Alcathous, stabbing him in the chest. Idomeneus mocks Deophobus’ brag that he has had revenge, since he has only killed one Greek for three Trojans killed.

Idomeneus boasts his lineage from Zeus, through Minos and Deucalion, and challenges Deiphobus to fight. Deiphobus decides he would be best to have help against Idomeneus. He finds Aeneas standing idle. Aeneas is angry that Priam skimps on his honours. But Alcathous, who has been killed, was Aeneas’ brother-in-law, and Deiphobus uses this fact to persuade Aeneas to help him. Aeneas charges at Idomeneus, but Idomeneus is too experienced to be frightened. Nevertheless, he now calls for aid, saying that Aeneas has the advantage of youth over him. Aeneas now also calls for support, and as troops gather, the battle begins to concentrate around them. Idomeneus and Aeneas fight. In the course of the fight Idomeneus kills Oenomaus with his spear. He tries to strip the body of its armour, but he is forced to fight a defensive retreat. As he fights Deiphobus tries to spear him, but he misses and hits Ascalaphus, son of the god Ares. But Ares does not notice. He is in Olympus, held back by the will of Zeus.

Deiphobus strips Ascalaphus’ body of its helmet, but he is wounded by Meriones who stabs his outstretched arm. Polites, Deiphobus’ brother, rescues him and helps him get back to Troy.

Further fights and deaths ensue. Aeneas slits open the throat of Aphareus. Antilochus stabs Thoon as he tries to escape. Antilochus fights off Trojans as he tries to strip Thoon’s body of armour, and Poseidon helps him. He turns away Adamas’ spear, which lodges in Antilochus’ shield. In return, Meriones spears Adamas between the genitals and naval, leaving him to suffer a painful death.

Helenus charges at Deipyrus and cuts away part of his head. Menelaus, angered at this sight, charges at Helenus. Helenus fires an arrow but it bounces off Menelaus’ chest armour. Menelaus drives his spear right through Helenus’ fist which is holding the bow. Helenus falls back into his ranks and is saved.

Pisander now attacks Menelaus, but Menelaus’ shield saves him from Pisander’s spear. Menelaus attacks Pisander with his sword. He hits him between the eyes and both eyes drop out onto the ground. Menelaus turns to the Trojans to berate them, expressing his anger at the theft of his wife, and saying that the war will turn again and the carnage will be visited upon the Trojans. He feels the Trojans have an unnatural desire for violence and bloodshed. Menelaus strips Pisander’s armour from his body. As he does so, Harpalion, the son of King Pylaemenes, charges Menelaus with his spear, but the spear is stopped by Menelaus’ shield. As he retreats, Harpalion is speared in the bladder by Meriones. Harpalion is carried back to Troy, where he dies.

Paris, enraged by the death of Harpalion, shoots Euchenor with an arrow. Homer relates to us the story of a prophecy: Euchenor knew he would either die from plague if he stayed at home, or die fighting at Troy. He has expected this death.

Hector, for his part, continues his assault on the Greek ships. This is where the Trojans appear to be having most success and the Greeks are under pressure to hold their defences. Both Little and Greater Ajax are holding their positions here. The fighters are engaging the Trojans, hand to hand, while the skilled Locrian bowmen are beginning to have a devastating effect against the Trojans, safe behind their fighters’ line.

Polydamus rushes to Hector to warn him that the battle is not going as well as he might presume. He acknowledges that Hector is a great warrior, but not necessarily a good tactician. He points out that Trojans who have broken through the Greek defences are mostly forced back again, or have to fight against overwhelming odds alone. He urges Hector to draw back his troops to plan a better strategy. Polydamus is also concerned that if Achilles feels directly threatened, he may yet join the battle.

Hector agrees to this plan, and orders Polydamus to take charge of the withdrawal while he goes to find other leaders. He discovers that Polydamus is right: key leaders, he learns, are dead or have returned to Troy, wounded. Hector berates Paris for continuing the battle when he was in a position to see what was happening. But Paris replies that not even he can be a coward all the time. He acknowledges the deaths or the wounding of important fighters, but Paris emphasises the importance of courage, and urges Hector to lead his men. Paris’ speech urges Hector on, and Hector’s leadership encourages the Trojans around him to fight fiercely against the Greeks again. Nevertheless, Hector cannot overcome the Ajaxes. Having stalled Hector’s advance, Greater Ajax rails against him. Ajax promises Hector eventual defeat and taunts him with the idea that the Trojans only have the advantage now because they have the support of Zeus. An eagle swoops by at this point, like a sign from the gods, and the Argive forces cheer. But Hector answers Ajax. He says he wishes he was the son of Zeus. But he says that the Greek defeat is assured, nevertheless. He taunts Ajax to fight.

The book ends with the Trojans launching into a frontal attack against the Greeks.

Hector is generally remembered as a great commander. Married to Andromache, father to Astyanax, he is often portrayed sympathetically against the libertine and somewhat cowardly Paris. When Paris fights Menelaus in Book 3, he is roundly beaten, but saved by the intercession of Aphrodite, who spirits him back within the walls of Troy. In Wolfgang Petersen’s 2004 movie adaptation, Paris, played by Orlando Bloom, cries and snivels in fear at Menelaus’ feet. Paris is a playboy, but not a real warrior. The fact that his chosen weapon is the bow and arrow suggests he avoids combat, choosing to kill from afar.

Eric Bana plays Hector in Peterson’s film, and Peterson portrays Hector as a level-headed warrior, faithful to his city, but also a mature husband who understands the risks he takes. That he must fight Achilles and lose is therefore tragic.

Book 13 offers us a different perspective on Hector. Hector, as ever, remains a mighty warrior, but he is a man not necessarily suited to lead, for all that. He is not a strategist, nor does he fight effectively as part of a team. He is so embroiled in his own battles, that he fails to read the circumstances of the wider battle. Added to that, he is easily persuaded. He is capable of making bad decisions on the battlefield.

Hector is not the main focus of most of this book, so this assessment is mainly supported by the scene with Polydamus and what follows. The Trojans are in danger of being pushed back to Troy under the barrage of Locrian arrows, when Polydamus rushes to Hector to urge him to pull the troops back. At this point, the narrator switches point of view and describes Hector as “headstrong” (line 838). Polydamus’ argument to withdraw begins with a critical appraisal of Hector:

Polydamus’ speech begins as a criticism of Hector’s self-involvement and overweening belief in his own talents as a fighter. Polydamus, by cataloguing the many talents afforded by the gods, draws the argument to the qualities he, himself, possesses – that of judgment – to prepare Hector to take advice from someone with less authority. Polydamus’ speechis a reminder that success relies upon the talents and efforts of many men. It also serves to puncture the illusion of the narrative that promotes a few heroes as worthy of song, against the thousands of anonymous men who fight and die unrecorded.

The implicit argument of Polydamus’ speech is that a good leader listens to wise counsel. Caught in the moment with Polydamus, Hector understands that the advice to retreat and revise tactics is good advice – “His plan won Hector over” (line 864) – but Hector is shown to be susceptible to flattery and personal challenge. That his evil angel should be Paris speaks strongly to Hector’s weakness: that he is not a tactician but a good fighter who, like Achilles, seeks personal glory, no matter what his commitment to the city and his family is. Hector leaves Polydamus to organise the retreat (it is hard to imagine the heroic Hector wishing to be in charge of that) to “meet the new assault” and give the other leaders “clear commands, rather than taking charge of an action without glory: that’s how I read it.

This impression is bolstered by the fact that Hector sees evidence that Polydamus has read the situation correctly. He finds many leaders dead or seriously wounded. The situation is so dire that he becomes angry with Paris who has been on hand to judge the situation and act as the leader that Hector, himself, has failed to be:

Appalled at the battle losses as he is, it does not take Paris long to undo Polydamus’ influence and persuade Hector to launch a headlong assault against the Greeks once again. Paris acknowledges the losses openly, but without reflection upon this he urges Hector to lead his contingent of men:

Against Polydamus’ tactics, Paris offers the more attractive “fighting spirit”, and seems to understand that Hector craves to be the leader of men in glory. What he offers Hector is more appealing to Hector’s character – glory – against what Polydamus offers, which is good council to retreat and make a better plan. That Hector is ultimately swayed by Paris’ flattering suggestion – so quickly his mind changes – rather than Polydamus’ criticism and good advice suggests that Hector is a good fighter but not the best leader. That he went looking for other commanders the moment he accepted Polydamus’ advice suggests his heart was never into the idea of a tactical retreat.

The book ends with Ajax taunting Hector and Hector taunting him back, spurred like two schoolboys to further conflict. That’s exactly what happens:

The cumulative effect of the repeated “and” suggests an army once again united in its resolve for slaughter.

Book 13 has little in the way of plot advancement, and the major characters are not involved in a lot of the action. It appears there is less artwork inspired by this book of The Iliad as a result.

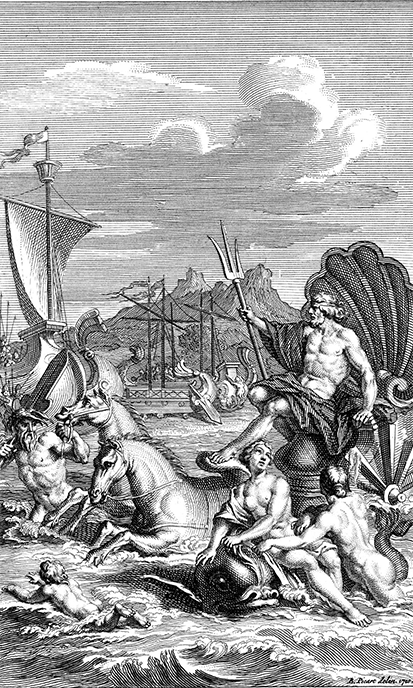

The two images below are representations of Poseidon (or the Roman equivalent, Neptune, to be accurate, in the case of the mosaic). Poseidon is the key god in this book of The Iliad. He favours a Greek win and he takes action in secret to thwart Zeus’ plans.

Bernard Picart’s illustrations for The Iliad are stately and static. Picart was a French engraver who mostly illustrated books like The Bible and Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In this image we see Poseidon arriving at the shores of Troy. His battle chariot seems to be reinterpreted as a throne, backed by a scallop shell, making him appear more stately, perhaps more aligning to notions of a Christian god dispensing justice. The trident stands in place of a sceptre.

The female figures adorning the base of the chariot are masculine, apart from breasts, recalling the treatment of the female form by Michaelangelo. The child in the surf and the figure who leads the horses to shore are not realistic figures in this environment, but appear to enhance Poseidon’s divinity. The child seems to lay on the waves rather than swim in the water. The figure leading the horses bears a strangely shaped sword we assume can be wielded by Poseidon.

Apart from that, the representation of the Greek ships seems more realistic than Crispijn van de Passe’s, as illustrated for the previous page that covers Book 12. The ships resemble triremes, and only one ship seems to be at full sail at the shore.

Habib Mhenni / Wikimedia Commons

To be fair, this image is of the Roman God, Neptune, the Romans’ equivalent of Poseidon, and it is not necessarily representing a scene from The Iliad. But it is interesting to compare Homer’s description of Poseidon preparing his chariot to this image, which highlights the majestic appearance of Poseidon’s war machine which is otherwise but aside the moment Poseidon reaches the shores of Troy:

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!