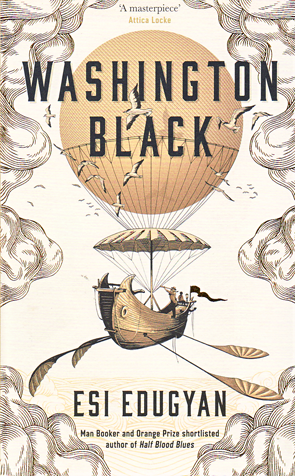

My edition of Washington Black has a beautiful cream cover with an airship, called a cloud-cutter by its creator, Christopher (Titch) Wilde. It is graceful, aloft amongst marshmallow clouds. I have to admit that I found the image arresting and it may be part of the reason I chose to read this book from the Man Booker shortlist this year. The craft, like the clouds that surround it, is static and symmetrical. The image is serene and suggests to me quiet, untrammelled scientific investigation within an eminently rational world.

Yet this is not the tone of the novel. It is neither a story about nineteenth century scientific discovery, nor are its protagonists rarefied Enlightenment thinkers. Unlike other books that draw upon niche historical facts from which to weave a story – I’m thinking of Tracey Chavelier’s Remarkable Creatures, the story of Mary Anning and Elizabeth Philpot, two female fossil hunters of the period – Washington Black is a different kind of historical novel. Esi Edugyan draws upon the history of the slave trade, but does not recount the typical fate of black slaves of the period. It draws upon the ever-growing interest in scientific investigation during the nineteenth century, but it is neither a champion of scientific rationalism, nor does it read as a searing indictment against the evils of the time. In the end, for me, the book’s power lay in its depiction of personal relationships and the weaknesses of individuals, never fully aware of the full impact and implications of their ways of thinking and their actions. You cannot know the true nature of another’s suffering,

Washington states, and he does not mean negroes exclusively.

The story begins in Barbados where George Washington Black, a negro boy about eleven years old, is forced to work on a sugar plantation as a slave for the new plantation owner, Erasmus Wilde. It is in this first section of the novel that depictions of slavery are typical of our most extreme expectations: one boy has his tongue cut out for talking back, another is burned alive for trying to run away. When the slaves begin to commit suicide, believing they will be reborn in their homeland, Wilde performs his most barbaric act: he has the head of a suicide slave cut off before his fellow slaves. No man can be reborn without his head,

he declares. Washington later reflects that it was the most dehumanising act, since Wilde’s action effectively extended ownership beyond death.

The book balances this barbarism with the appearance of Christopher Wilde, Erasmus’s brother, whom Washington is asked to call Titch, a name given to him in childhood. Titch is an abolitionist who initially asks his brother for Washington’s aid because he is the right weight to act as ballast for his flying machine. However, Washington soon proves he has unexpected talents. He is a fine drawer, useful for the recording of scientific specimens, and shows an aptitude when Titch begins to teach him to read and write. The pair seem to form a bond, and Washington experiences a more civilised life under Titch’s tutelage. However, when a cousin, Philip arrives on the plantation with bad news and then later commits suicide, Washington is in danger once again, since he witnessed the suicide and will be blamed for the death as part of Erasmus’s ongoing quarrel with Titch. Titch and Washington escape Barbados on the Cloud-Cutter, but soon crash it into a ship at sea during a storm. From this point on, Washington is on the run from the bounty hunter, John Francis Willard, and is propelled into numerous adventures spanning the globe, from Nova Scotia, where he seeks the society of the black Loyalists, to the Arctic, England and later Africa.

It is from this point in the novel that I think the story strays from the more typical depictions of slave issue, even if Washington can never escape the reality of being black. The novel is divided into four parts and is somewhat episodic. I thought this contributed to a sense that its sections lacked some depth or detail. At one point, Washington is lead underground through an open grave to a station

for the underground railway, recalling Colsen Whitehead’s eccentric depiction of that cause in his novel, The Underground Railway. However, for me, after the first part of the novel the issue of slavery informs the thematic concerns of the novel rather being central to it.

Part of these thematic concerns are expressed in the protagonist’s name. Named after America’s first president of the new constitution, Washington’s life is governed both by the Enlightenment values that informed America’s Constitution and Bill of Rights, as well as the fact that George Washington was a slave owner. America encapsulates these contradictions. This duality is repeated in the novel, from the Wilde brothers – Erasmus, a man in support of a system of slavery, and his scientific brother who supports its abolition – to the twin Kinast brothers, Theo and Benedict, ship surgeon and ship captain respectively, who save Titch and Washington when their aerostat crashes into their ship. Oddly, their roles on board the ship echo the different responsibilities of the Wilde brothers on the plantation – scientist and man in charge – yet they both prove to be enlightened men, moulded by their upbringing by a doctor after they were orphaned and having learned the loyalty of orphan children they have in turn saved.

After the slave plantation in the first part, the novel takes on a picaresque character. Washington, at first having no other option but to follow Titch to the Arctic in search of his father, is later forced to live upon his wits and make a life of his own, first through menial jobs and later through his new mentor, G.M. Goff, a famous naturalist who has published books on marine life. He has a beautiful daughter, Tanna, who shares her father’s scientific enthusiasms.

But Washington, himself, encapsulates the contradictions of the age. If science and Enlightened thinking find correlation with those who find slavery anathema, science also justifies slavery. When Tanna, intending to show her admiration for Washington, says Washington Black would never be a slave, even if he was born in chains

, Washington rebukes her: …you speak of slavery as though it is a choice. Or rather, as though it were a question of temperament. Of mettle. As if there are those who are naturally slaves, and those who are not. As if it is not a senseless outrage. A savagery.

His rejection of racial essentialism finds its opposite in the words of the bounty hunter, Willard:

Is it natural to sever low beings from their true and rightful destinies? From their natural-born purpose? To give them a false sense of agency? As if some creatures are not put here in the service of others. As if cows don’t exist to be eaten . . . Nothing is accidental in the works of nature. Do you know who said that? Aristotle. He said, Nothing is accidental, everything is, absolutely, for the sake of something else.

Yet Edugyan does not allow a simple dichotomy to develop between slavers and abolitionists, whites and blacks, wrong and right. Washington is a creature of both the white science and the world of slaves. He has been raised to believe in an ancestral home after death, yet at the same time he has been exposed to scientific thinking. Titch teaches him, That is nonsense, Washington. When we die, there is nothing. Only blackness. Forever and forever.

When Washington is engaged by Goff to gather sea specimens for a London museum, it is Washington who comes up with the idea of creating an aquarium of live specimens and undertakes the difficult task of making it a reality. Yet Washington only vaguely understands that the octopus he captures – his prize exhibit – languishes in his care in much the same way that slaves languish in their captivity; that he has reduced the creature to the service of science, if not a plantation.

I found Washington Black to be a little uneven in quality. The first part of the book which recounts the conditions of the slaves in Barbados is gripping. The character of Erasmus Wilde is threatening and lacks humanity. Other sections of the book were inclined to be less realised in their detail or characterisation, tending to be, as they were, shorter scenes set to transition the focus of the story from the plantation to Washington’s later independence in his role as a marine scientist and his search for answers to his past. Some of the action is reminiscent of the novels of Jules Verne – 80 Days Around the World and 20,000 Leagues under the Sea for instance – but the focus is not so much on the wonder of the world (this is not a science fiction story as Vernes’s tended to be) as on the moral choices the characters make and the extent to which their upbringing and experiences have led them to make those choices. These are people whose characters might be described in broad terms like ‘racist’ or ‘philanthropist’, but no character seems to be wholly one thing. They are freed from moralising determinations of their actions, and the novel, instead, allows a freer exploration of the impetus that drives individuals to enlightenment or darkness.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!