Remarkable Creatures is the story of the friendship between Mary Anning and Elizabeth Philpot, two women from very different backgrounds who both became known as fossil hunters in the early nineteenth century.

Elizabeth Philpot is a middle class spinster who, together with two sisters, has to move to Lyme Regis on her brother’s marriage, as they can live more cheaply there than in London. This small plot detail is similar to the start of Jane Austen’s Sense & Sensibility, a fact I mention only because Jane Austen herself was a visitor to Lyme Regis, and possibly bought fossils while there. Elizabeth becomes fascinated by the fossils she finds on the beach in Lyme Regis, and begins to collect them. She meets Mary Anning, the best fossil hunter in the town, and slowly forms a close friendship with her. Elizabeth’s main interest is in fossil fish, and she becomes a specialist in them. A source of pride for her is the exhibition of one of her finds in the British Museum, with her name listed as the finder - well, her surname at least – as being female, she cannot be fully acknowledged by the Museum.

Mary Anning is an uneducated, working class girl who hunts for curies (the local term for fossils) to sell to tourists, to make money to help support her family. Mary’s father is a drunk and a failing cabinet maker who is obsessed with fossils, and who introduces his daughter to them. When he dies, Mary’s fossil hunting becomes the main source of income for the family.

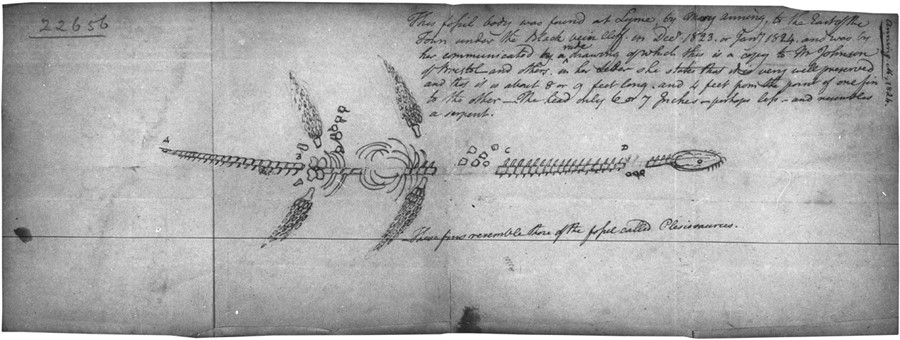

Mary has an eye for fossils, and is quick at spotting unusual items. When she is about 12, she and her brother find the head of a ‘crocodile’ in the rocks. While searching for a body she is sure must also be there, Mary is almost killed by a landslide. It takes two years of storms and further rock movements before that part of the cliff is uncovered again, but eventually Mary finds the rest of the ‘crocodile’. Although most people call the fossil a crocodile skeleton, Elizabeth has seen sketches of crocodiles and cannot accept that Mary’s fossil is the same creature. Gradually Mary and others come to share this belief, and eventually the creature is identified as an ichthyosaur, a creature which lived between 250 million and 90 million years ago. Mary later also discovers the first complete skeleton of plesiosaur.

Later in life (beyond the period covered by this book), Mary finds the first British pterodactyl fossil, and is the first to identify the round rocks known locally as bezoar stones as being fossilised dinosaur faeces (or coprolites).

Despite the huge number of finds Mary makes, her working class background and being female led to her being largely unacknowledged for her discoveries. Most of her finds were identified in collections as being made by the (male) person she sold them to. It is an early source of anger for Elizabeth when she finds Mary’s first ichthyosaur displayed in a London museum, the local landowner is listed as the discoverer of this amazing find. When Elizabeth confronts about this, he defends himself with …Mary Anning is a female. She is a spare part

. Despite the lack of formal acknowledgment, Mary’s reputation grows, and many geologists and other scientists seek her out to assist them in making the finds they need to add to the growing evidence that perhaps the Bible is not to be taken literally, and that perhaps the Earth is slightly older than the 6,000 years that was accepted at the time (according to Bishop Ussher, God created Heaven and Earth on the night preceding 23 October 4004 BC). But females are not permitted to write for scientific journals, nor are they allowed to attend sessions of the Geological Society. Not even when discoveries made by them are being discussed.

It is clear from the book that both Mary and Elizabeth are passionate about fossils and that their knowledge far exceeds that of most of the males who seek Mary’s help in finding their own fossils. Mary was largely self-taught, after being encouraged by Elizabeth to learn to read at Sunday School. But she is observant, and through her years of patient searching for fossils, became an extremely knowledgeable scientist. The book provides an interesting insight into the life of a woman who made an extraordinary contribution to science and who was largely unacknowledged for her contributions. But apart from that, the main appeal of this book for me was the discussion of religion and the gradual dawning on Elizabeth and Mary of the impact of their discoveries on the generally held view of the literal truth of the Bible.

I had discovered from conversations I’d had about fossils with the people of Lyme that few wanted to delve into unknown territory, preferring to hold on to their superstitions and leave unanswerable questions to God’s will rather than find a reasonable explanation that might challenge previous thinking. Hence they would rather call this animal a crocodile than consider the alternative: that it was the body of a creature that no longer existed in the world. This idea was too radical for most to contemplate. Even I, who considered myself open-minded, was a little shocked to be thinking it, for it implied that God did not plan out what He would do with all of the animals He created. If He was willing to sit back and let creatures die out, what did that mean for us? Were we going to die out too?

I enjoyed this book. I thought Tracy Chevalier recreated the feeling of the age perfectly, especially with the scene where Elizabeth impulsively leaves the London house to attend an auction alone and realises that society’s conventions will not allow her to walk from Soho to Piccadilly alone. It’s hard for me as a modern female to fully understand what it would have been like to live in that age as a female, especially for an intelligent woman like Elizabeth, but Chevalier describes that world so perfectly I felt like I could feel it. I liked how the book switched between Elizabeth’s and Mary’s points of view in telling their stories, and I liked the description of the growing conflict between established religious beliefs that were being challenged by scientific discoveries. But I didn’t love this book. I guess I wanted it to be more about the science and less about the friendship. I thought it got a little overly sentimental at times and lost track of the main message (at least to me) to focus on a possible romantic side story that didn’t really interest me and that I felt was unnecessary to book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!