Last year I bought a hammock. Despite my generally overwhelming desire to persist in a state of constant relaxation, I'd somehow never used one before; but, after discovering a portable hammock stand that required next to no effort to set up anywhere, I bit the bullet. It arrived in late fall — far too close to winter, when even the sunniest days were unfailingly cold, making my sofa my preferred lounging apparatus.

Recently, we had the first day of spring which could unanimously be considered “nice”, and I knew just what I wanted to do . . . what I’d longed to do many times throughout the winter. As advertised, setting up the hammock took mere minutes; and as I lay there, swinging gently in the soft breeze and finishing the last few chapters of The Wager, a fleeting thought unironically crossed my mind: this is the same comfort that the seamen aboard the titular ship would have enjoyed to recuperate after a hard, fulfilling day sailing the ocean blue.

I then reminded myself what an idiot I am, because I’d just read this book, and I now knew the hells a life at sea inflicted upon these unwitting men . . . men who were clearly and utterly doomed, even before the damn shipwreck. To compare any aspect of my life to theirs would be insulting at best.

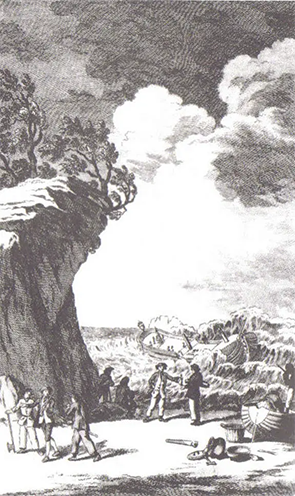

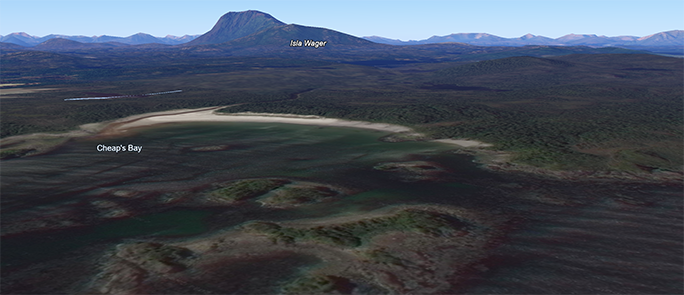

The Wager, authored by David Grann, pieces together the largely-forgotten events that befell the crew of the HMS Wager, a British man-of-war that was sunk after striking rock off the coast of southern Chile in 1741. Those that survived the wreck — a group that included, I would be remiss to point out, the grandfather of the English poet Lord Byron — found themselves stranded on a harsh, inhospitable island which offered little food. As they often do, tensions split the crew into factions, pitting the ship’s fledgling but determined captain against the seasoned, charismatic gunner.

I won’t go into too many details in this review, suffice to say that individuals from both factions made separate, desperate escapes, eventually returning to England where they once again started pointing fingers at one another (this isn’t a spoiler; it’s called out on the book jacket). If you’re curious about what transpired, you could go check out the Wikipedia entry right now if you wanted to—it’s titled “Wager Mutiny” — but I’d highly advise against doing so if you have any inclination of reading this book. What Grann has done here weaves these events into a compelling narrative, providing a dramatic but faithful account of the abject miseries experienced by these men, both as sailors and castaways.

You may have scoffed a bit when I described this work as “dramatic but faithful”, and you would be justified for doing so. We encounter plenty of examples in media of facts being skewed for the sake of entertainment. Nobody sees the words “based on a true story” and expects a historical account. And yet The Wager lists over 200 reference sources, making for a sizeable count of pages, all hiding in the back of a book that you’d never expect to find a bibliography in. In his notes, Grann recalls opening a “dusty, mouldering manuscript” and deciphering smudged entries written in text he describes as “small and squirrelly”. In addition, he also spent three weeks exploring the island where the sailors were held captive, as well as the surrounding lands and seas. You can’t claim the man didn’t do his homework.

And that’s what makes The Wager an astounding piece of work. Grann presents the facts as they are, provides the accounts straight from those who wrote them. He believes you’re smart enough to render your own judgement on these men, and refuses to mince words or pick sides, or even claim that they said something if there was no record of them doing so. But what else you get from Grann — what you’ll never get from Wikipedia — is context. All that research went in to filling in the cracks, as it were; painting a picture of the daily struggles, the insurmountable odds, and all the little details in between as accurately as possible so that you have a complete understanding of what these people were experiencing when they made the decisions that they did.

I could complain that the epilogue to the Wager saga is a little anticlimactic, although this is something Grann can’t be penalized for; and indeed, he makes it clear why it ended the way it did. Again, he was never trying to show these people as anything more than they were, never presenting them as heroes or victims, but simply as humans who made very human decisions, and ultimately, led very human lives. Perhaps that is the downside of relaying a truthful narrative; it lacks the grandiose appeal of an epic showdown, a battle between good and evil, or a happily-ever-after. But life is rarely any of these things. Some days, life is contentedly swinging on a hammock in your backyard on the first sunny day of spring; other days, life is slowly decaying in the bowels of a ship with your peers as you all succumb to scurvy, or foraging for seaweed on a windy, bitterly cold island, just to stave off starvation for one more night. There is no greater meaning to it; it is just what it is, and trying to wrap it up in some neat little bow to make some sense of it is ultimately a futile effort.

That said, I realize that trying to imbue meaning into something is exactly what I’m trying to do to end this review right now, so I’m going to take my own advice and just let it be. It’s a good book. Bye!

Other Books by David Grann

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!