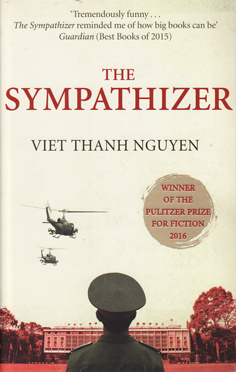

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen was a great read. It chronicles events at the end of the Vietnam War, which I only vaguely remember from television news of the time. I was only nine years old when Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese. It was years later that I saw images of the evacuation by helicopter off the top of the embassy building. In the past I have remembered these images somewhat inaccurately, as though they showed an orderly movement of people, instead of what I see now when I return to them, of the ant-like ladder of humanity stretching precariously up to a helicopter on the embassy roof, and another image showing an overloaded helicopter virtually escaping as the panicked human ladder plunges under the force of its own gravity.

The Sympathizer is essentially a spy story, although it also eventually chronicles a class of people often derided in the late seventies: the boat-people

. Asian faces were a rare sight for me growing up in the western suburbs of Sydney, so I tended to think of anyone Asian as having likely escaped by boat from a situation of which I had little understanding. Nguyen uses this epithet in his novel, but he does not embrace it. There was always something derogatory about it, and his protagonist, the Captain, is aware of this:

Collectively we will be called the boat people, a name we heard once more earlier tonight, when we surreptitiously listened to the Voice of America on the navigator’s radio. Now that we are to be counted among these boat people, their name disturbs us. It smacks of anthropological condescension, evoking some forgotten branch of the human family, some lost tribe of amphibians emerging from ocean mist, crowned with sea weed. But we are not primitives, and we are not to be pitied. If and when we reach safe harbour, it will hardly be a surprise if we, in turn, turn our backs on the unwanted, human nature being what we know of it.

Anyone reading the novel – in fact I looked up a few reviews on Amazon before beginning my own and they tended to focus in the same way – will likely describe the book in terms of the protagonist’s flight from Saigon and his return to Asia, but may not consider the problem the Captain sees here: one of representation. How you are perceived, in the media, within the culture and ultimately as a human being, rests upon this.

The story, itself, is told by the Captain as a confession. The captain is a double agent, a North Vietnamese, or Viet Cong, who has planted himself deep undercover to spy on the South Vietnamese and American forces. When his South Vietnamese general and his family need to make preparations to flee the city, the Captain is entrusted with the organisation. The Captain flees with the general and his family to America, along with his long-term friend Bon, who is unaware of the Captain’s traitorous sympathies, while leaving behind their best friend, Man, also a North Vietnamese sympathiser. The Captain speaks perfect English, long a student of Western culture. He is also a bastard, being the off-spring of a liaison between a French priest and his underage mother. In so many ways, the captain is a man of divided sympathies, divided identity and divided priorities.

Nguyen relates this story in crisp prose. His writing is dramatic and reflective. The story, related in prison as a kind of confession, contains the doubts, justifications and needy honesty of a man in his position. However, it also has its light, humorous moments, too. I had to reread a laugh-out-loud incident he relates concerning his early teenage years in which he has an amorous encounter with a squid, soon to be on the table for dinner. At the back of my mind I had a thought, that you just can’t make this kind of thing up!

But beyond the surface of the story I felt there was something else at stake: the issue of identity and who gets to define you: the problem of representation. The Captain is a man of torn loyalties and mixed race. Where does he belong? He tells us in the opening page of the novel that his talent is always to see at least two sides of any situation: I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces. Perhaps not surprisingly, I am also a man of two minds.

Ensconced as he is in the house of his enemy, his curse is his sympathy for individuals, his understanding of the point of view of his enemy and his general interest in American culture.

One of the most interesting sections of the novel for me was his trip to The Philippines as an advisor to a movie auteur intent on making a film about the Vietnam conflict. It is not hard to see, and Nguyen admits in his acknowledgements, that Coppola’s Apocalypse Now was the inspiration for this section of the novel. The Captain’s motivation for cooperating in this little bit of Western fantasy is to affect a more positive representation of Vietnamese people in the film. But he feels he fails:

They owned the means of production, and therefore the means of representation, and the best that we could ever hope for was to get a word in edgewise before our anonymous death. (234)

The Captain addresses the problem of representation in other aspects of the narrative too. The English scholar, laughingly called Richard Hedd, portrays the Vietnamese population as little more than animals who need to be subjected to conditioning via American firepower to make them politically pliable:

The Vietnamese peasant will not object to the use of airpower, for he is apolitical, interested only in feeding himself and his family … airpower will persuade him that he is on the wrong side if he chooses communism . . . (186)

Interestingly, it is Hedd’s Englishness that places him at the pinnacle of an imagined cultural hierarchy, which allows him to criticise the ideologies of America – the idea of the pursuit of happiness is dissected by him as a goal denied to most Americans in reality:

Refugees such as ourselves could never dare question the Disneyland ideology followed by most Americans, that theirs was the happiest place on earth. But Dr.Hedd was beyond reproach, for he was an English immigrant. His very existence as such validated the legitimacy of the former colonies, while his heritage and accent triggered the latent Anglophilia and inferiority complex found in many Americans.

Dr Hedd, along with the Captain’s conception of his people as boat people

, reminded me of a term in G.E.M. de Ste Croix’s The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World: labour aristocracy

. He argues that easily exploited immigrant labour stabilises class conflict in capitalist economies by allowing the large sections of the indigenous classes to engage in labour aristocracy by acquiescing to the exploitation of immigrant members of the working class. That these exploited sections of the community may be disliked, even reviled for a time (in Australia think of European immigrants in the fifties, Asian immigrants in the seventies and eighties (and the stir the historian Geoffrey Blainey created on the back of these prejudices), or the present debate over Muslim immigration) is like a social release valve. J.D.Vance’s book, Hillbilly Elegy (also reviewed on this site) suggests the social and political implications for a nation when this kind of paternalistic superiority is denied poorer social classes as society progresses beyond the stage of the easily exploited immigrant; when there is no one further down the ladder to look down upon.

Edward Said, in his study of Orientalism, had a different term for this kind of thing. He suggested the idea of othering

in which a sense of self identity is created and maintained by the representation of a class or race of people who are not us. In achieving this, thought is divided by binary opposition, simplifying the world into a set of dichotomies that are potentially harmful to those on the negative side of this two-sided conception.

Never is this simple conception better illutsrated than when the Captain secures a job in the Department of Oriental Studies at a university. The department chair, an old fossil of seventy or eighty, believes in Kipling's dictum, that East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.

To demonstrate this, the chair gives the Captain a homework assignment, to divide a page in two, titled ORIENT and OCCIDENT, and to characterise these opposing worlds in a series of lists. Naturally, what is achieved is a list of cliches that serves to do little more than confirm the chair's prejudices.

This is what struck me as I read the Captain’s account. Neither fully French nor Vietnamese, a North Vietnamese soldier sympathetic to Southern Vietnamese people, a communist enthralled by American culture, the Captain does not easily belong to any one side of the defined dualities. He is sympathetic in the emotional sense of the word and a sympathizer in the pejorative sense. When he is asked to write a confession, he is incapable of writing anything deemed acceptable because his personal insight is greater than ideology, race or nationality.

It’s hard to talk any more about this without giving away some great scenes and revelations in the novel. But my point is that while you can take it for granted that this is a great espionage novel, I think it is more than that. This is perhaps the first novel I have read by an author of the surname Nguyen. That Viet Thanh Nguyen has told this story from the perspective of a North Vietnamese goes some small way to address the problems of representation.

Naturally there are many more incidents and insights the novel has to offer beyond this review, which has necessarily narrowed its discussion to a limited range of issues. Apart from some great action pieces, as well as intriguing and entertaining scenes, the novel works because it portrays a wide cross section of humanity, which is part of the point I have tried to make about representation. The Captain, alone, is a complex, flawed and likeable individual and the moral choices he is forced to make in the novel are compelling. This is a book I would highly recommend.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!