The Missing Partners was written by Major Sir Henry Lancelot Aubrey-Fletcher, 6th Baronet and Lord Lieutenant of Buckinghamshire, under the pen name Henry Wade. Although a founding member of the Detection Club, Wade doesn’t seem to have made it into The Golden Age of Murder by Martin Edwards, so I have only limited information on him from Wikipedia. He seems to have been fairly prolific, with his main detective being Inspector Poole (featuring in seven books). My edition of The Missing Partners identifies it as Inspector Poole #1, but this isn’t correct: Poole is not in the book at all.

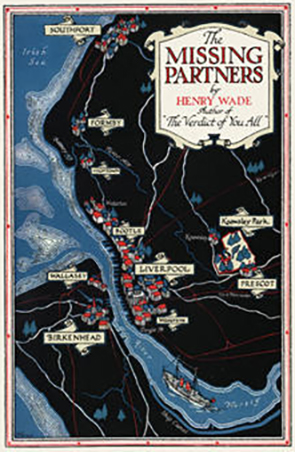

The Missing Partners has an unusual setting, at least from my (so far) limited reading of the Golden Age. Most Golden Age mysteries are set in either London or somewhere rural. The Missing Partners is set in Liverpool which makes for a nice change. The docks of Liverpool and the characters who inhabit them are quite nicely described, creating an authentic sounding setting. The titular partners are the cousins James and Charles Morden who run a shipping company. One Friday morning neither of the cousins appears at the office, a fact which disturbs Herbert Mildmay, office-manager and his daughter, Helen Mildmay, secretary to the partners. The Mildmay’s find it difficult at first to get anyone to take their concerns over the absences seriously. Not even James’s wife, Lilith, is overly worried at first. Eventually, the police are convinced enough to start a search which results in the discovery of James’s body, washed up on the banks of the Mersey. Charles appears to have left for New York which instantly focusses suspicion on him. If this was a modern book, Charles might have been able to escape, as no one is on his tail for a few days. As it is, he has to travel by steamship, so he is caught as he disembarks.

Helen is convinced Charles is not the murderer, and co-opts Tom Fairbanks (clerk at the Tax Inspector’s Office) and William Turnbull (Morden’s Solicitor) to help her work out what has really happened. In their endeavours they are up against Superintendent Dodd of Liverpool Police. Dodd is rude and condescending to them, and inclined to ignore any evidence that doesn’t support his theory that Charles is the murderer. But once he gets started on a lead, he determinedly follows it through to the end. While he seems determined at first to arrest the obvious suspect and close the case as quickly as possible, he turns out to be the one who solves it all. Our amateur detective team are the type of characters who are generally the most appealing in this type of book; the ones we follow and want to come out on top. But not these: all three are generally irritating characters who I doubt will appeal to most readers. But it is their interactions that keeps much of the plot rolling along and maintain the interest, particularly in seeing which of the two suitors Helen will settle for.

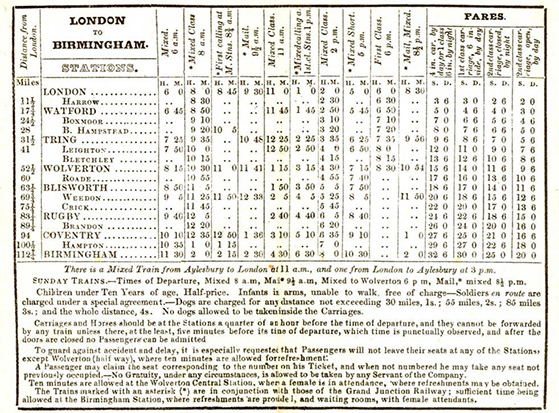

I did think at one point this was going to be similar to an Inspector French mystery, as Dodd initially devotes several pages to studying his Bradshaw and working out possible train schedules, both for the absconding Charles and for his police force in pursuit. But the story pulls back from being dependent on complicated timetables, while becoming complicated in other ways.

The plot soon moves on from being solely about the murder, and is expanded to cover tax evasion (always a favourite with me, professionally speaking), prohibition in the US and the profits to be made by smuggling whisky. There are also a few side complications such as the ownership structure of Morden’s Shipping and various infidelities amongst the characters.

I found this to be a fairly standard Golden Age mystery, with clues scattered at regular intervals, found by both the police and the amateur detective team. The plot moves quickly, and I found this a quick read. There was a sudden twist at the end which caught me by surprise. What surprised me even more was that it was Dodd who noticed the importance of an offhand remark made by one character, as he previously seemed determined to ignore every piece of evidence which did not fit his own theory. I had fallen into the trap of not believing him capable of solving the murder, and I have to credit Wade for the surprise reveal which allowed Dodd to prove himself to actually be a competent detective.

Overall, this was an enjoyable mystery and a fun read.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!