I received my copy of this book from the author. However, I have not discussed this book with the author, nor has Chris McGillion had any input into the writing of this review or the ideas and opinions expressed in it.

The Coffin Maker’s Apprentice is the third book in Chris McGillion’s East Timor Crime Series. By now, McGillion’s characters are well establish. Sara Carter is the American cop from Arizona whose own troubled past has contributed to her less-than-ethical treatment of a suspect, earning her a posting to Timor-Leste as an investigator for INTERPOL. Vincintino Cordero is the Timor-Leste investigator originally tasked with the job of hosting Carter and translating for her. And Estefana dos Carvalho has been assigned to help Carter, too. Over the course of the first two books they have solved some difficult crimes and have formed a bond. Cordero has come to respect Carter and he realises she is attractive. And Carter and Estefana have formed an increasingly close friendship, too. This book is at that stage in a series when the stories of the characters, themselves, become more a focus for story. This is the point when, if there were movies or a television series made from these books, the tagline would be ‘This time its personal!’

That’s because the titular coffin maker’s apprentice, Josinto Veddo, has been abducted, and he is the fiancé of Estefana. Josinto gets a mention three times in the previous book, The Sand Digger’s Skull, but plays no part in that story. Now, he becomes the central focus of an investigation conducted by Carter, Cordero and Estefana. Two other young men have been found dead, both with betel quids placed in their mouths. A quid is typically a mixture of areca nut, betel leaf and spices which is chewed to produce a mild narcotic effect. It leaves the teeth stained red. The placement of the betel quids in the mouths of the victims is reminiscent of other stories like Thomas Harris’ The Silence of the Lambs, in which a killer places the pupa of a Death's-head hawkmoth into the mouths of his victims. As readers (and viewers of film) we have been trained to understand the significance of a killer’s call sign. It is a communication. But what does it mean?

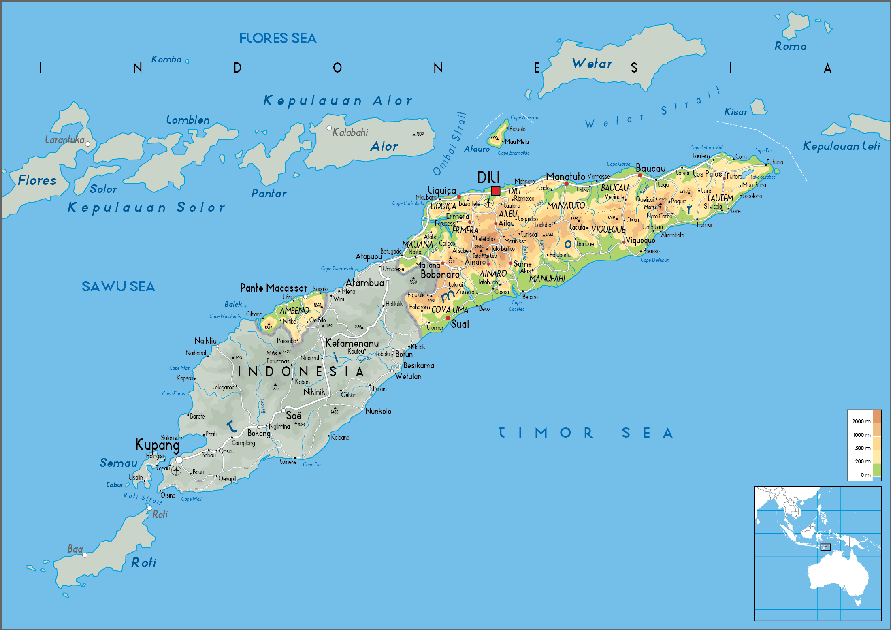

The Coffin Maker’s Apprentice is typical of books in this series. They read like light, entertaining crime fiction, but you have a sense by the end of the novel that the book is about more than just the solving of a crime. McGillion doesn’t burden his reader with long disquisitions about history or philosophy, but the history of Timor-Leste is ever-present in each narrative, and the question of the nation’s character and future is as of as much importance as its past. There is always a balance between the interests of the local story, and the presumed knowledge and experiences of the reading audience. McGillion is an Australian author but he aims to appeal to an American audience, too. So Cordero is a native Timor-Leste cop who has been raised in Australia after his family fled the country’s troubles during Indonesia’s occupation after 1975. And Carter is an American cop who has worked with Native American communities. She extrapolates this experience to try to understand the people of Timor-Leste and her role there. By extension, she represents the general reader who knows nothing or little about Timor-Leste.

Timor-Leste only gained its Independence from Indonesia in 2002 after a vote in 1999. Aspects of that vote and events leading up to it are a subject of the previous two books. The Coffin Maker’s Apprentice is set in 2014, only twelve years after Independence, and only eight years after the 2006 riots which began with protests by members of the military and resulted in gang warfare throughout Dili and the deployment of international forces to help quell the situation. Cordero’s concern is that the two killings represent gang violence and the possible return of a gang conflict in Dili.

Beyond the police procedural of McGillion’s narratives is the question around Timor-Leste’s past and future, which is skilfully interwoven with the personal preoccupations of his characters. Carter, for instance, was pressed into service in Timor-Leste, and now that her three months’ service are concluded she looks forward to returning to her home in America. But there are moves by her INTERPOL boss, Danique Jacobson, and US Ambassador Hudson Taylor to extend Carter’s secondment. Carter is torn between the relationships she has built and the good she is doing in the country, with her desire to return home and resume her life. It’s a dilemma which is subtly paralleled by Senyor Pereira’s experience. Formerly a cabinet maker, the direction of his life was changed when he was forced to make coffins after Indonesia took control of the country in 1975. He remained in the job. Now in his sixties, Pereira is too old and set in his life’s course to change.

Carter is at a pivotal moment which could potentially change her own life course. Howard Brooks, the coroner, tells Cordero that “Perhaps she needs saving from the direction her life is taking.” Cordero, he intuits, could be the man to effect that change.

For his part, Cordero is also at a pivotal moment in his life. He has a growing attraction to and admiration for Carter. He is faced not only with the question of whether he should act on his feelings, but with the problem of understanding them. Cordero, who confides in Brooks, explains the impact of Carter’s grief over the loss of her father and sister to a violent act in America. But Brooks has no tolerance with backward-looking: “Grief, remorse, regret. The lives ruined by such things.” Brooks has been married twice. Both marriages ended in divorce due to infidelity, either his own or his wife’s. Brooks has a pragmatic attitude to love: “Love grows cold.” But Cordero separates the influence of passion and love. “I think you’re talking about passion not love,” he tells Brooks.

For Cordero, passion was what he experienced as a young man at university. For love, he has his father as a model: a journalist whose newspaper was shut down for criticising the Portuguese administration of the country; who took his family to Australia to escape the Indonesian forces; who worked menial jobs to keep his family together. For Cordero, the difference between passion and love is between a short-lived desire – a judgment he makes about Brooks’ marriages – and a long-term effort to build and nurture a future; a selfless act. Later, Cordero sees ‘passion’ for Carter expressed in the lascivious comments and intentions expressed by Officer’s Lucas and Manuel. Needing them for an operation they are not obliged to do, Cordero uses their desire to persuade them to help with the promise that Carter and Estefana will be accompanying them. The question is, would ‘love’ truly be Cordero’s motive in changing Carter’s life direction?

Love, grief, fate, identity. These are issues with which the characters struggle to define themselves and find purpose. They are themes McGillion has woven skilfully into his narrative since the first book of the series. Carter describes to Cordero in The Crocodile’s Kill her memory of her father’s death when he tried to prevent the abduction of Rebecca, Carter’s half-sister; a memory that sometimes fuels her anger and violence which resulted in her posting to Timor-Leste. Cordero’s response suggests to us how to read these books. He tells Carter you can never get over grief, but he makes a distinction between grief and anger:

You have to keep the two separate. Look at this place. Think of all the killing and dying that’s gone on here. Timor-Leste is a country full of tragedy. But we memorialize it. That way, it’s contained as a grief and doesn’t consume us in anger.

The narratives of these novels resolve around a series of dichotomies. Between the modern and traditional; science and superstition; peace and violence; Western and Eastern values: between love and passion; grief and anger; self-determination and fate. Together they suggest a nation at its own pivotal moment in its history. Its people are still dominated by tradition and superstition, which remains purposeful in many villages, but which is increasingly challenged or in conflict with Western values that the country cannot escape. It is a tension between ‘backward-looking’ and the ‘future’: between living with and memorialising the past. McGillion deals with these issues thoughtfully and sympathetically.

This novel begins with a terrible moment in Timor-Leste’s history. It is 1984 and three men of the Falintil guerrilla force are weakened by extreme hunger. They are killed by Indonesian forces as they seek food. Thirty years later their bodies are being reinterred at the Heroes Cemetery in Metinaro where the tombs of the nation’s first president, Xavier do Amaral, and the first prime minister, Nicolau Lobato, are located. Lobato’s body, however, is not in his tomb. He is presumed to have been killed by the Indonesians and his body has never been found. The reburial of the three guerrilla fighters is not only a way to honour them, Eurico Guterres, an anthropologist, tells Cordero, but it is also “the state claiming to correct the horrors of the past for a bright future.” It is a ‘proper’ burial, we understand, in contrast to the two youths murdered at the beginning of the story, one of whom was unceremoniously dumped in a water trough. And on the other side of this bright thought – about a ‘bright future’ – is the rumours abounding, based on an old story, that Lobato will resurrect and lead a resurrected army. Present, past and future; the idea is central to these novels.

Which makes Estefena and her fiancé, Josinto Veddo, the coffin maker’s apprentice, of importance. Josinto may barely appear in the narrative, but his relationship with Estefana also represents a future Timor-Leste; a hope. As Cordero’s own experience has shown, love is as much about creating a future as personal desire. So, this time its personal, but the story is also about the young country in which it is set. Highly recommended.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!