I received a copy of this book from the author. However, I have not discussed this book with the author, nor has Chris McGillion had any input into the writing of this review or the ideas and opinions expressed in it.

On the 7 May 2009 The East Timor Law and Justice Bulletin contained the following curious paragraph:

Timorese Police Deputy Commander Inspector Afonso de Jesus has called on residents in the capital Dili not to believe in rumor-mongering that there was a witch named Margareta flying around in some places.

It seems beyond belief that enough residents could have believed a witch was flying about their city that this was written. But in the last few months I have watched news reports that show some people in America think Donald Trump is a new incarnation of Jesus Christ, so there’s that.

Margareta gets a mention in Chris McGillion’s The Sand Digger’s Skull. It’s a novel that has cause to consider superstitious and rational beliefs, weighing traditional values against modern. Nevertheless, it’s still the kind of book you could take for a lazy read on a holiday. McGillion’s setting is exotic enough to give the narrative an appealing flavour, and highly readable, so that the story clips along without effort. If you’re not familiar with Timor-Leste, the small country in the east of Timor which shares the island with Indonesia, the setting may read like an exotic place conjured for the titillation and delight of the reader. This is a place of crocodiles, forests, and villages still tentatively edging towards modernity, but steeped in the old ways of sacred places, ritual and witchcraft. However, if you consider yourself a more serious reader, you may be concerned about the fetishisation of ancient cultures or of the Orient, and their exploitation for fiction. But in the case of McGillion’s writing, an author with a long association with Timor-Leste, there is a rare balance achieved between readability and interest, as well as a thoughtful and insightful treatment of the challenges faced by Timor-Leste and its people.

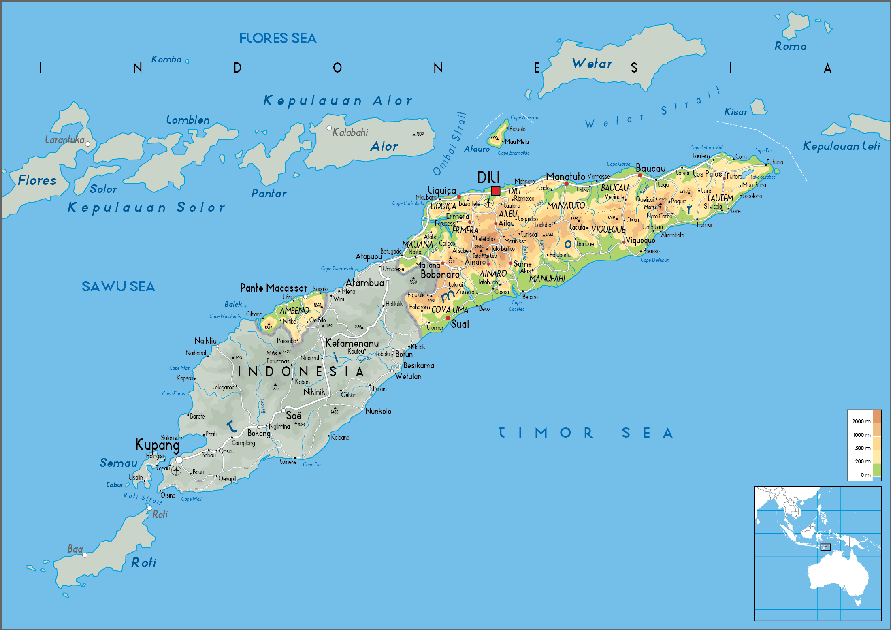

The Sand Digger’s Skull is the second in what is currently projected to be six books in the ‘East Timor Crime Series’. As I write, the third book, The Coffin Maker’s Apprentice, is being released this month and the fourth book has been submitted to the publisher. The first, The Crocodile’s Kill, was a skilful police procedural steeped in the country’s history and culture, centred around the abduction of babies from East Timorese villages. In this second book, McGillion again produces a compelling police procedural that immerses his reader in the world of the East Timorese. Timor-Leste is a young country still struggling to overcome its history of colonial occupation (by the Dutch and Indonesia, and briefly occupied by the Japanese in World War II) and fully adapt to the tenets of a modern democracy and rule of law. It is a country with poor infrastructure and isolated villages.

A sand digger – one of many people who excavate sand by hand to supply construction sites in Dili – has found a human skull buried in the sand that shows signs of violence. When Vincintino Cordero is dispatched to investigate another five skulls and partial skeletons are unearthed, as well as the skeletal remains of a foetus. There is evidence of machete marks on some of the bones, but most of them appear to be decades old: all except the bones of the first skull, which appears to be more recent. Vincentino Cordero and Estefana dos Carvalho are tasked with travelling up the Comoro River to try to locate the area from which the bones were washed away, and to investigate the more recent murder. And given that there was a history of killings by Indonesian militia during occupation, especially during the period close to the vote for Independence in 1999, Carter’s presence as a representative of INTERPOL is also required to investigate the possibility of war crimes.

The team travels along the poor roads of Timor-Leste to Fatisi. In this village they are presented with a complex network of traditional authorities, represented by the headman, the elders and the spiritual head, Sabu Bada, the lai-nain, as well the representatives of the Catholic Church, Father Roque de Franca and two nuns, Sisters Felicia and Agnes. Carter, Cordero and Estefana must try to win the confidence of the villagers, even though their world has not been substantially improved by the modernising efforts in Dili. Free State education is available to the young, although their school teacher is lazy and incompetent, and the young mostly leave for want of local opportunities. The older generation’s beliefs are shaped by thousands of years of custom, and theirs is primarily a moral world shaped by the sacred, along with the opposing forces of spirits and witches which must be held at bay by traditional justice. The laws of Dili and modern democracy have little sway in this part of the country, and the three officers find that their status as police officers is not always helpful; that they must contend with the prejudice of a population represented by elders who have little regard for modern laws which challenge their authority and beliefs.

The tension between modernity and tradition is the nexus of this story. Timor-Leste has suffered a history of occupation, war, massacres and the painful birth of its nation as a modern state, with its constitution incorporating the protection of and rights of its citizens under a democratic government. Central to an understanding of modern Timor-Leste, as Cordero and Estefana understand it as representatives of the law, is the rule of law. Against the interests of the modern state – that its laws should be preserved within the judicial system which it has created – is the interests of the village, populated by people without modern education, whose world experience is limited to within a few kilometres of where they were born, and for whom superstition is an imaginative but essentially real response to the vagaries of the world.

As such, Western values of justice and even the notion of a crime novel is measured against these traditional beliefs. If we consider ourselves to be that more ‘serious’ , perhaps more aware reader, we may already be uncomfortable at the thought of Western – we might say White – paternalism in fiction: the danger of denigrating one culture in the service of the tenets of Western empiricism and Enlightenment beliefs.

But McGillion’s narrative is more sophisticated than that. In the first instance – and this is a perspective the author would find a little offbeat, I suspect – reading the novel is like reading a kind of science fiction (not literally) which sheds a light upon Western countries like America and its pretensions to rationality and lawfulness. After all, so much of science fiction acts to displace our own world and its issues. Frank Herbert’s Dune addressed elements of the oil crisis through the drama on Arrakis. Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War was a metaphor for the issues around the Vietnam War and how it affected veterans and society, told through the story of an interstellar war. Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed pitted the tenets of Capitalism against Anarchism on the twin worlds of Anarres and Urras. How else do we look at ourselves, except from afar? In this instance, McGillion offers perspectives which challenge the assured rational hegemony of Western thinking.

Foremost among characters who question this assuredness is Father Roque de Franca. Exiled to Timor-Leste by his own church for questioning church tenets, Roque has struggled with his own theological doubts, but nevertheless recognises that Christianity has provided Western culture with a progressive framework:

Christianity, you see, represents a huge leap in human consciousness. We know it as the idea of redemption or salvation. But what are we being saved from? Answer: the assumption that we are forever condemned to live as those before us have lived.

Against this is the usual question of traditional cultures’ application of abstract thinking to an understanding of the world: the ability to identify or conceptualise what is not immediate or anticipated. But Father Roque suggests that the experience of the East Timorese is to imbue their world with a projection of their own emotions, and that what Western ideology labels ‘primitive’ is, “in fact, highly imaginative, highly intellectual but in ways different to rational thought as it developed in Europe.”

This is the nexus upon which the story reflects our own world. With all the advantages of modern America, Carter concedes, “forty percent of Americans think the world is only 10,000 years old and two percent think the earth is flat.” It is difficult to argue with that.

For Western readers, and American readers most particularly, Timor-Leste represents a part of the evolution of our own democratic social institutions. Timor-Leste is a country in its infancy, struggling to establish these institutions. There is not an all or nothing dichotomy between tradition and modernity but rather, a blend within the culture and even within individuals, of ‘rational’ tenets and more atavistic influences. As Warren L. Wright, quoting Xanana Gusmao, on the occasion of the International Conference on Traditional Conflict Resolution & Traditional Justice, states:

[T]raditional laws ... represent the stage of evolution of a society and usually correspond to societies based on feudal relationships both in the social and religious …

Having to deal with traditional beliefs and superstition is part of the problem facing the investigators. And they are not immune to its influence. Cordero ritually sacrifices a chicken before entering liluk (sacred) land, while Estefana is unwilling to enter liluk land and offers anecdotal evidence that witches are real. For her part, American FBI agent Sara Carter has become sympathetic to the beliefs of Native Americans.

But there is neither a simple assumption in this book that traditional culture is wiser or should maintain a privileged position in a modern world. Father Roque, a radical priest, suggests that it is the breaking with tradition that is liberating. Bobby Kennedy, he tells Carter, “by the time he himself was killed he’d become perhaps the most truly radical leader your country ever produced”, and asserts, “It’s when people break those bonds, like that second Kennedy, that they become free to change history.”

This is the tension that underpins the drama of this novel. The Sand Digger’s Skull is not merely a simple police procedural because it encourages its reader (if the sway of the hammock and beach sun hasn’t entirely addled the brain) to consider the implications of a history of imperialism and colonialism that now burdens Western countries with moral ambiguities. And the story represents a moment in the putative social evolution of Timor-Leste. Faced with a series of killings, Cordero, Carter and Estefana must assert the authority of the State, otherwise the fledgling State of Timor-Leste cannot exist; governments are nothing without their laws and the means by which they can be enforced. Set against this is traditional law, which exists outside the bounds of the modern state. It’s a dilemma that is local, but has international implications. Is Timor-Leste progressed by the tenets of the modern state, and how does an international community resolve its own complicity in the denigration of traditional societies and their cultures? Naturally, the narrative has to come down somewhere on these issues – after all, it’s hard to justify extra-judicial killings which primarily affect the poor and women – but McGillion’s story reveals the complexity not only of the question of law and tradition, but of the realities of a society emerging as a modern state.

If all this sounds too heavy, I promise you’ll be throwing back a tequila and following along in your hammock without a thought to the underlying ideas of this story, if that’s what you want, as though all McGillion wanted to do was to get you to the end and find out who done it and how. That’s how crime fiction is supposed to work, right? But McGillion shows it also has the potential for so much more.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter