In Greek myth, Elektra was the daughter of Clytemnestra, who was the wife of Agamemnon, who led the Greek forces against Troy in the Trojan War. When Agamemnon returned from the war about ten years later, Clytemnestra got him all cosy in a bathtub and then dispatched him with an axe. Her reason? Agamemnon had sacrificed their first daughter, Iphigenia, to appease the goddess Artemis, so that the Greek fleet might leave Aulis where they were stranded without wind to fill their sails, and launch with favourable winds, to Troy. Now, Elektra and her brother, Orestes, feel compelled to take vengeance against their mother for the murder of their father. But first, Orestes must spend long years in exile while he grows, protected from Clytemnestra’s new lover, Aegisthus, who has ambitions to take back the throne of Mycenae which once belonged to his father. Meanwhile, Elektra enters into a humble marriage with a farmer so she cannot be married off to a foreign king and sent away from her home.

This is the subject of Jennifer Saint’s second published novel, Elektra. The story is well known, although the details may vary from other versions you might have read. There are always variations in myth. Constanza Casati, for instance, in her novel, Clytemnestra, presents a very different story, even though the bare bones of the plot are the same. Casati introduces an obscure plot variant in which Clytemnestra first marries a foreign king, and her husband and baby son are then murdered by Agamemnon so that he might have her for himself. Already, one can see, this would be a fraught relationship, even before Iphigenia gets the knife on the beach at Aulis. Jennifer Saint, on the other hand, sticks to the more conventional story in which Clytemnestra’s first husband is Agamemnon. She sees Agamemnon as glamorous, even if she is initially reticent, but when her marriage is arranged, she accepts it with equanimity.

Saint’s adaptation is a skilled and compelling read which faithfully renders different elements of the legends associated with Elektra. To do that, she tells her story from the perspective of three women: Elektra, whose story for the most part of the novel is actually the least compelling; Clytemnestra, who lives with the consequences of her revenge against Agamemnon; and Cassandra, the Trojan princess, daughter of King Priam, who foresees the destruction of her own city and is taken back to Mycenae by Agamemnon after the war. These multiple perspectives provide a more rounded version of the story than Casati, and they allow the reader’s sympathy to reside with more than one character. But in doing this Saint’s adaptation is more conservative. While her characterisations may be just as strong – stronger – the overall effect is that the novel feels less insightful. Its thesis feels weaker because the ending is hard to reconcile with the sympathy Saint has built with her reader for Clytemnestra, and because of the mean-mindedness of her titular heroine.

This does not mean that where Saint’s version remains faithful to traditional accounts, that it is weaker. Sometimes, she uses this to advantage. Take Aegisthus’ character, for example. Casati’s Aegisthus is a sympathetic character who returns to claim the throne. Casati reimagines him as an enlightened man whose character seems more aligned with modern sensibilities. When he sees the leadership Clytemnestra provides Mycenae, for instance, he is willing to support her claim rather than press his own. Of course, Aegisthus also has his own backstory, common to both Casati and Saint. His claim to the throne rests on his father’s tenure as king. Aegisthus’ father, Thyestes, had challenged Atreus, his brother, for the throne, and it went back and forth between them. Outside the scope of Saint’s story is the details of Aegisthus’ birth. Thyestes raped his own daughter, Pelopia, on the advice of an oracle who predicted the son of such a union would kill Atreus. Aegisthus was the son of this union and he did kill Atreus, helping to reinstall Thyestes on the throne. There are also some terrible details of cannibalism mixed up in all this, though not Aegisthus’ fault. But back to the point: in Casati, Aegisthus is deferential and willing to accept Clytemnestra as his ruler. He even deals with bullies who pick on a girl in a bar. He seems an all-round nice guy and a hero. But Saint’s portrayal of Aegisthus is more traditional. In the plays of Aeschylus and Euripides, for instance, Aegisthus was a loathsome usurper who was too cowardly to take action to seize the throne, himself.

And this is the characterisation we get with Saint, too. Even from the most sympathetic perspective, Clytemnestra first describes Aegisthus as “awkward-looking” and “nervous”. Elektra is less complimentary. She describes him variously as “mean and scrawny-looking”; a “craven, hesitant, rat-faced wraith”; a “mangy dog”; a “diseased branch of the family”; and with a nod to Shakespeare – Richard III – Saint has Elektra describe Aegisthus as “stunted and misshapen, an insult to our blood.” As if this isn’t enough, Saint has Aegisthus kick a dog (rather than save a girl from bullies), and the dog then dutifully dies of old age to emphasise Aegisthus’ villainy. Further to this, we see that Aegisthus is not suitable to rule. Clytemnestra describes that Aegisthus’ “narrow shoulders did not fill the broad back of his monstrously gilded and towering chair.” Failing to fill this chair, the throne, is the royal equivalent of failing to fill a pair of metaphorical boots. On so many levels, Aegisthus is a villain not up to the task.

The advantage in this for Saint’s novel is that her Clytemnestra is a more complicated and nuanced character by her association with this Aegisthus. It is easy to hate a man who has killed your first husband (Casati) and to love another who proves to be worthy of trust, but Saint portrays Clytemnestra’s weaknesses and missteps and still makes her a sympathetic to us. Clytemnestra is willing to marry Agamemnon to begin with, and she is later quickly taken in by Aegisthus on the strength of his hatred of Agamemnon, alone. When Agamemnon is killed, she finds she has little in common with Aegisthus, whom she realises she cannot trust because he now has reason to murder her children, especially Orestes, to consolidate his own power. Ironically, she has placed her living children in danger to avenge the murder of her dead daughter, Iphigenia. Her distress does not need explanation.

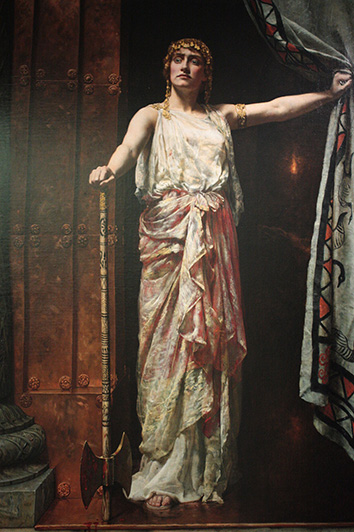

Saint’s treatment of Clytemnestra is arguably better than Casati’s, who devotes her whole novel to her reformation and redemption, reviled as she was in ancient times. After all, modern retellings of these myths are implicitly about giving a voice to the voiceless women of history and myth. Cassandra is a particularly apt example in Saint’s novel. In all stories about her she is a woman who is ignored or disbelieved. Joining the Temple of Apollo at a young age rather than marry, she hopes to receive the kind of visions her mother, Hecate (also known as Hecuba), receives. When the god Apollo appears to her in the temple he gives her this gift, but spits in her mouth and curses her when she rejects his advances. Her curse is to see visions of the future without anyone ever believing her. Cassandra may receive visions that foretell the death of loved ones or the fall of Troy, but she is powerless to take actions that might prevent their fulfilment. When she arrives in Mycenae, her life destroyed and now a concubine to Agamemnon, her story, told from her perspective, reminds us of the powerlessness of women throughout history, especially in times of war. At the same time, Saint’s Clytemnestra reacts differently to Casati’s, showing sympathy towards Cassandra, and thereby humanising Clytemnestra further.

In doing this, Saint makes Clytemnestra even more, not less, sympathetic. Elektra’s name may be on the cover, but her story is secondary to these two women. Clytemnestra is destined to kill Cassandra, but Saint ingeniously engenders a simple but powerful sympathy in Clytemnestra for Agamemnon’s concubine. When Clytemnestra first sees Cassandra, her attention is drawn to the girl’s tangled hair, her downcast eyes and a bruise on her temple: “I feel something touch me, pressing right into the raw wound of my soul. All at once, I have to blink back tears.” This “raw wound” is her sense of loss for Iphigenia, and Clytemnestra immediately perceives the tragedy of a daughter, not the public humiliation of a lover in her house. Clytemnestra orders that Cassandra be treated kindly. “No kindness,” she reflects, “can ever make up for what we have done to her …” Cassandra is another daughter torn from another family, and somewhere is another grieving mother. That Clytemnestra kills Cassandra is immaterial to this. Even in the murder scene Saint skilfully evokes the sense of connection and empathy Clytemnestra has for her victim, knowing that she is committing a welcome mercy, not vengeful violence.

Elektra’s suffering, on the other hand, is dwarfed by her mother’s compassion and Cassandra’s suffering. It is hard to feel for her what we feel for the other two women. Elektra may be driven by the same desire for revenge as her mother, but her towering anger is not tempered by compassion or self-awareness. When Elektra hears of Cassandra’s death, she implicitly perceives her as rival lover:

No one has told me how she died. I wish that I could have talked to her: perhaps she could have told me stories about my father. The slaves say she was a princess of Troy. She was so lucky to be chosen by a king, the greatest king in Greece, to be brought here to a palace that must be as fine as the one she left. Finer, I’m sure. Whatever wealth Troy possessed, Mycenae had Agamemnon. And she did too, for a little while.

Elektra’s obtuseness is staggering. While Clytemnestra could pity the girl who has lost her family and home, Elektra perceives Cassandra to be a girl lucky to have come to Mycenae with her father, despite its leading to her death; despite the loss of family and home which she had not “left” willingly. Cassandra’s one advantage, from the perspective of Elektra, is the presence of Agamemnon which she craves with the fierceness of a lover. Elektra’s capacity for empathy is negated by the yearning for her lost father, transformed into a type of sexual desire. When she lays in bed at night thinking of her father on the beach of Troy, she thinks of his suffering, which evokes a restless sexual energy in her: her “lungs about to burst”, her hair clinging “damply to my slick temples”, Elektra feels a frustrated energy that elides any understanding of the suffering of the slave girl she imagines lying next to her faraway father. Instead,

… every fibre of my being ached with longing – every part of my wretched body yearned to be amidst the smoke of campfires, beneath the rough canvas of a tent; to change places with a slave who had nothing except the thing I wanted most of all in the world. My father’s arms around her.

Even Briseis, the slave woman taken from Achilles as part of a dispute with Agamemnon (causing Achilles’ withdrawal from the fighting) is a subject of sexualised fantasy. Elektra imagines Briseis taken to Agamemnon’s tent. Her imagination is so vivid that she almost supplants Briseis in this fantasy: “I could almost feel the sand of the Trojan beach trickling between my toes.” In Elektra’s mind Briseis’ misery is a source of erotic potential:

The soldiers’ hands would hold her upper arms firmly as they led her towards the tent. She would look down as they approached, her unbound hair falling across her face until she stood before him.

It is not a great step to take, with such strong evidence as this throughout the novel of Elektra’s desire, to make a case that her revenge is that of a jealous lover against her mother. If this assessment seems extreme, it certainly didn’t to Freud who perceived the same energy (despite whatever you think of psychoanalysis). The story of Elektra is one of two Greek myths that Freud drew upon as he developed his theories of psychoanalysis. Oedipus, who unwittingly married his mother and killed his father lends his name to the psychoanalytic term, the Oedipal Complex. The Oedipal complex describes a child who strongly identifies with a parent of the opposite sex and feels themselves in competition with the same-sex parent for attention. That’s a broad and simple definition, but it will do for our purposes. When applied specifically to boys, the Oedipal Complex is similar to the Elektra Complex, applied specifically to girls. In Jennifer Saint’s Elektra, we meet an Elektra so enamoured of her father, she is unforgiving of her mother’s crime and can find no pity or develop any insight into her mother’s suffering.

Elektra’s seething desire for revenge is what drives the novel once Agamemnon is dead. And following Elektra’s reasoning there would seem to be a moral equivalence in revenge for a revenge. But this is not so. Clytemnestra commits murder, but her motivations are stronger and her internal struggle more nuanced than Elektra’s. She knows instinctively from the start that the cycle of vengeance in the family must end. She is merely naïve enough to believe it ends with her. She fully understands the terrible train of events begun by Tantalus, Agamemnon’s great grandfather, when he first tried to humble the gods, and their subsequent effect on generations of the family. It is for this reason that she asks Agamemnon to spare Aegisthus when he overthrows Thyestes. And when she is driven to kill Agamemnon, she realises the terrible role she has played in perpetuating the Curse.

Saint’s portrayal of Elecktra, on the other hand, feels on par with Euripides’. Saint’s Elektra is harsh, single-minded, inflexible and unsympathetic. She sees the mercy shown to Aegisthus as nothing other than a mistake: a weakness. As for her sister, Iphigenia, sacrificed by her father at the age of fourteen, Elektra finds no sympathy in her heart for her sibling or for her mother’s grief. She says to Clytemnestra,

Iphigenia was a sacrifice. The gods demand a heavy price sometimes, and it is an honour to pay it. I wonder what they will ask of you, to atone for what you have done. If that could even be possible.

Elektra’s anger is unrelenting and she refuses any compassion for the situation her mother faced. Georgios, the simple farmer Elektra marries, is far more insightful. He understands revenge to be like the cycle of the crops: revenge is always planting hatred to be harvested in the future for an immediate retribution that brings no remedy. Elektra, however, affirms that, “The gods can’t forgive us until we put it right. We have to make the murderers pay.” But through Cassandra we have seen the gods directly. Apollo is inscrutable, demanding, uncaring and torturous. It is Apollo who finally commands Orestes to take revenge.

The resolution of this story is on Elektra’s terms, and that is where Saint’s approach is difficult to evaluate. As a modern writer, Casati’s strength lies in her willingness to reinterpret her source material; to make it relevant to a modern audience. But it is never certain that Saint is doing quite the same. For all her skill in writing and characterisation, it sometimes feels Saint is immersed in her source material. For instance, on the subject of Iphigenia’s death, Saint has Clytemnestra digress to tell a version of the sacrifice which does not accord with what she has just witnessed: a version told to her “A long time later” that has Iphigenia replaced by a deer for the killing blow. The purpose of the digression is for Clytemnestra to dismiss this euphemised version and make her audience (and herself) bitterly embrace the reality. But it also feels a little like Saint is unwilling to set aside the role of the scholar here. Instead, she chooses to remind us of a variant version, as she occasionally does, when she might remain with the truth of the story she is telling. This variant is from Euripides’ play, Iphigenia as Aulis which wasn’t produced until the late fifth century BCE, long after the events that take place. As such, the reference is a tiny chink in the fourth wall, and a hint that Saint is tied closely to her sources.

This approach made me wonder about the ending of the novel. Saint brings her story to a conclusion, as is warranted by the source material, but there is little reflection upon the crime Orestes and Elektra have committed, or any personal insight. Clytemnestra’s murder feels less like justice than Agamemnon’s. Elektra’s suffering has not been on the same scale as the suffering of Cassandra or Clytemnestra. She loses her father to her mother’s murderous revenge but she was young when he left for Troy, and in the moments that she has to spot him as he re-enters Mycenae, she has trouble identifying him. Instead, he seems to reside in Elektra’s imagination as a sexualised absence. Though she marries Georgios, she explicitly tells him that their marriage is a convenience, not a real marriage. Only Pylades, who returns to Mycenae to help Orestes take revenge, is a suitable replacement for her father. For his part, Orestes’ desire for revenge is merely an extension of his sisters’, who has indoctrinated him to hate on behalf of a man he never knew. Elektra’s revenge, it seems, is not driven by a moral precept, but an intense sexual retaliation against her mother. It's a more traditional approach that plays into psychoanalytic theory, but that is how Saint paints the situation. As the only first-person narrator left to speak at the end of the novel, Elektra has little to offer by way of insight. Instead, the scene slips into cliché: “The sun is a bright gold disc, climbing into the blue sky.” We have already been apprised of the meaning of Elektra’s name at the very start of the novel: “When I was born, it was our father who named me. He named me for the sun: fiery and incandescent.” Now, Elektra, Orestes and Pylades, arm in arm, “walk away together, into its light” and the meaning of the scene is no greater than the meaning of a fond memory of a father.

Elektra never rises to the level of self-awareness of her mother and Cassandra. But in the last pages of the novel her hopeful vision of the future, predicated on little more than a metaphorical ending that plays with her name, is not a lot to offer, even if the epilogue provides us with a vision of their happier future lives as a coda to the devastation caused by the Curse. Cassandra and Clytemnestra’s narratives have dominated the novel, and in this last section, when Elektra’s voice could shine (excuse the pun), she has little more to say. I’m still wondering how I feel about it. After all, Saint has produced an excellent novel which is well-paced and insightful. But the ending, for me, felt lost to a writing process that has produced an excellent book that, in its final ascent, was not capable of rising above its source material. Of course, that applies if you believe Saint has missed an opportunity. I said I wasn’t sure. It could easily be that Saint intended that her novel should end in moral ambiguity and we, as readers, should see the terrible irony of Elektra’s certainties, which destroy her mother and the humanity she brings to the story. Either way, Elektra is a novel worth the read, especially if Greek mythology is your thing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!