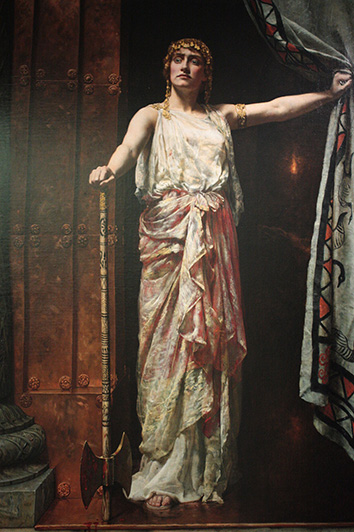

Clytemnestra’s story is told by Aeschylus in his plays Agamemnon and The Libation Bearers. She receives a pretty harsh assessment. She kills Agamemnon, her husband, in a bath upon his return from the Trojan War, making her guilty of mariticide and regicide all with one swift chop of her axe. Her son, Orestes, returns in The Libation Bearers to avenge his father, thereby adding parricide to the growing list of crimes in the plays. Clytemnestra is shown to be an unnatural mother and wife. She dreams she gives birth to a snake which then sours her milk when it bites her nipple. It’s prophetic. Clytemnestra is generally dehumanised in imagery used to describe her: she is a snake, a black widow spider weaving her web of deceit and, oddly enough, a moray eel. The anti-female rhetoric culminates in The Eumenides, the third play in the trilogy, when Apollo argues that Clytemnestra’s death was a justified killing because, as a woman, she had no legal rights regarding her daughter. The sacrifice of Iphigenia by Agamemnon was Clytemnestra’s motive for murdering her husband, but that is not good enough, even though Orestes will be acquitted for his mother’s murder. No one seems to blink at this argument in the play. Different times! For a more nuanced explanation of all this, you can check out my review of The Oresteia.

Given the recent spate of retellings of Greek myths, it was always likely that Clytemnestra’s story and her character would receive a modern reassessment. Costanza Casati offers us this reimagined Clytemnestra. Casati traces Clytemnestra’s story, not from the moment that she is ready to kill her husband, as we find in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, but from her teenage years growing up under her father, Tyndareus, in Sparta, alongside her siblings, Helen, Timandra, Castor and Polydeuces. We follow Clytemnestra through the harsh environment of Spartan education. Like boys, girls are meant to learn to fight and to use weapons, and sometimes this leads to injuries, sometimes, even, to death. Clytemnestra is a good fighter, easily the equal of many men, and she approaches life with an unsentimental strength that her beautiful sister, Helen, lacks. But she is not immune to life’s vicissitudes. We witness Clytemnestra’s marriage to Tantalus, and then Agamemnon’s brutal murder of her husband and child to force her into an unwanted marriage with him. What is worse, her own father is complicit in this plan. Despite her fortitude of character, the death of her husband and child is too much, and further to this, the later death of her beloved daughter, Iphigenia. Clytemnestra is tricked into taking Iphigenia to Aulis in Boeotia where Agamemnon awaits. Iphigenia, Clytemnestra, is told, has been promised as a bride to Achilles in the hope that the marriage will raise morale among the troops who are stranded on the shore without a wind to take them to Troy. Instead, Iphigenia is forcibly taken from Clytemnestra when they arrive and sacrificed to Artemis to appease the god and restore the wind.

Casati’s prose is serviceable, as is her approach, though its attempt to evoke an ancient society feels decidedly modern on occasion. This is a modern retelling, after all, for a modern audience. But there are awkward moments in the writing which might reflect the effort of a first novel. When Casati uses the image of an ice bucket tipped over the face to describe the jarring effect of a word, I found the image just as jarring. I was reminded immediately of the ice bucket challenges being widely undertaken on social media a few years ago, and the illusion of the fiction was momentarily broken. There were also two instances where sex scenes were marred by Casati’s technique. Her image of two knives slicing each other, cutting at the bone, was an odd metaphor for sexual pleasure, even if it was more apt to the purpose than the bucket of ice. Then there is a scene in which Clytemnestra and Leon ‘comfort’ each other. It is almost laughable after the drama of Iphigenia’s death. Her hands and knees are scraped and bloody. He is bruised and battered. She stumbles. He helps her up. He leaves to find a wet cloth to wipe her face, her hair and legs. She gazes, “into his umber eyes, strong and comforting, like tree bark.” (What an odd image!) Then he starts sobbing, so it’s her turn to comfort him. Now we are in the realm of comfort eroticism! They kiss and tremble and she grasps him hard, “knowing the pain would give him pleasure.” Next, “they tore the clothes away from each other’s bodies and flinched as they touched each other’s wounds.” The scene is lifted from a thousand Hollywood movies where comfort, not sex, is on the menu, but really, we all know where this ship is heading.

Mostly, Casati’s prose doesn’t trip up the narrative. Like I said, it is serviceable prose without pretension, getting one bit of the story told and moving on to the next bit, like building a wall in a linear-narrative kind of way. We all know where the story is headed, or readers could if they choose to read around the subject, first. From scene to scene, we see the wrongs done against Clytemnestra, and we understand her outrage.

Although, Casati has chosen to tilt the scale somewhat further on the outrage meter, just to be sure we understand. If you have read around this subject, one thing that might stand out is Clytemnestra’s marriage to Tantalus. Clytemnestra’s first marriage is to Agamemnon in most versions of this story. However, Casati seems to take a cue from Euripides who has Clytemnestra marry Tantalus first in his play Iphigenia at Aulis. In Casati’s version, Tantalus is introduced as the King of Maeonia, in Lydia, and his outrageous and pitiable murder and the murder of their infant son means he is not to be confused with the Tantalus who ate with the gods and incurred their wrath when he fed them his son, Pelops. That Tantalus is supposed to be the great grandfather of Agamemnon and Menelaus, a fact which is recorded in a family tree at the beginning of Casati’s book. This can be a confusing detail, especially since it is currently confused in some AI responses online which have Clytemnestra’s first husband identified both as the Lydian king and the great grandfather of Agamemnon and Menelaus. If we can separate that ambiguity from our minds, what we understand is that Casati’s version of events makes Clytemnestra that much more justified in her eventual revenge, since her forced marriage to Agamemnon after the murders is truly horrific. After that, Iphigenia’s death is awful, too, but it feels excessive. On the subject of Clytemnestra’s justification for revenge, to paraphrase Jerry Maguire, “You had me at Tantalus.”

Casati also works hard to redeem the character of Aegisthus. Aegisthus is the son of Thyestes, who is, himself, the son of the ill-fated Pelops who was turned into god pâté. So Aegisthus is the grandson of Tantalus: not the murdered Tantalus who is the first husband of Clytemnestra, but the bad boy who is sent to the Underworld by the gods as punishment for his trick with the menu. Aegisthus’ own brothers were murdered by Atreus, too, the father of Agamemnon and Menelaus, and served for dinner to their father, Thyestes. Greek myth has a lot of child consumption, it seems. In Casati, Aegisthus goes on the run when Agamemnon and Menelaus take Mycenae back from Thyestes, and he later turns up there again during the Trojan War while Clytemnestra is the sole monarch in Agamemnon’s absence. In Aeschylus, Aegisthus is a fairly unlikeable character. He exaggerates his role in the killing of the king, and he anticipates taking power from Clytemnestra.

Casati gives us a different Aegisthus. It is Polydamus, one of Clytemnestra’s elder advisers, who predicts Aegisthus will seize the throne, but we see no evidence for it. Aegisthus respects Clytemnestra, unlike Menelaus who sees women on par with other possessions: “Cows, women, goats, princesses, call them as you wish. They are all the same to me.” Aegisthus fights Clytemnestra, sparring as he would another man: a sign of their equality in this culture. When he first returns to Mycenae, Aegisthus comes with the intention of killing Clytemnestra to serve his purposes of revenge, but stays his hand because he hears of her reputation as a leader, running Mycenae, “far better and more efficiently than Agamemnon”. In fact, Aegisthus admits, “You make a far better ruler than I ever would”, and is willing to undertake a subservient role as her adviser. He proves more enlightened than the elders of the city who feel Clytemnestra is no longer an appropriate leader when they discover she has taken a lover, as opposed to Agamemnon who sleeps with young girls without consequence.

Highlighting this double standard, of course, is core to this novel’s purpose. Women in Sparta are raised with more freedoms than women in other city states, but they are not equal. Helen, Timandra and Clytemnestra are defined by a prophecy which characterises them as unfaithful women long before they are, foretold by a hateful priestess who has been sleeping with Tyndareus, anyway. Women are defined by the culture and their characters circumscribed by the expectations of marriage, childbirth and, if they are of a high status, the political connections they bring. To possess or take women is indicative of power, and so attitudes like Menelaus’ merely reflect these attitudes. So the possession of women is an issue that often arises without thought to the desires of women. Theseus kidnaps and rapes Helen. Castor and Polydeuces are falsely accused of kidnapping their cousins, Phoebe and Hilaeira, whose willingness is no bar to the violence that will follow a demand to return them. That women should exercise sexual autonomy goes against the grain of the culture and the representation of power achieved in having them. Men, like Theseus, can commit crimes but still be thought heroes: “Heroes like him are made of greed and cruelty: they take and take until the world around them is stripped of beauty.” But Timandra, Clytemnestra’s younger sister is forced to fight almost to the death for her lesbian desires. When Tyndareus has to officiate over the matter of a Spartan warrior taking another’s wife, it is Castor and Polydeuces, long before they are falsely accused of kidnap, themselves, who advise a strong punishment or hefty fine for the man who took her. Only Clytemnestra sees it as a matter in which the woman’s desires must first be determined.

This is a man’s world. Tyndareus supports Agamemnon and Menelaus over the matter of killing Tantalus because he identifies with their situation – the emasculating situation of exile – and he is uncertain of his own power in their presence. Tantalus, however, isn’t strong and Leda, Clytemnestra’s mother, doubts his suitability as a husband. Clytemnestra sees in him a different strength. “He is clever and curious.” But this isn’t enough. Raw power is the force that shapes society, and Tantalus is murdered.

So, Casati reforms Clytemnestra and Aegisthus while highlighting the violence, cruelty and hypocrisy of their patriarchal world. Aegisthus is not the man who shrilly boasts and threatens the Chorus in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon: rather, he is a man of dignity and compassion. When Clytemnestra follows him and spies on his movements, she sees him, one night, remain composed when he is recognised by merchants in a tavern, even though they abuse him and call him a coward. Yet on another night he takes action in the same tavern against a man who abuses a young girl. It is simple and formulaic character building, but we get the point: both Clytemnestra and Aegisthus are better than they have formerly been portrayed.

What is missing from Casati’s version of this story is the gods, themselves. They appear in speech and are used to justify all manner of actions, including Iphigenia’s death. But Clytemnestra will have none of them, and we see them as little more than a convenience for patriarchal power and its narrative. After all, this is a modern retelling and Clytemnestra represents modern ideals about women, their place in society and their relationship with power. While Iphigenia death is justified by this narrative of divine need, Helen’s paternity is shielded with a neat myth that has inspired some great poetry, but remains ludicrous. Instead of the foreign visitor being attributed as Helen’s father, her pregnancy is attributed to a visitation by Zeus in the form of a swan. It’s ridiculous, but this is how face is saved. For Tyndareus, Helen’s father, a man who must keep face, this is a far more acceptable story. As modern readers, we see the machinations of the gods writ in the smaller exigencies of power and its preservation.

Casati’s tale is well researched, displaying a deep and personal connection to these characters. It is not hard to see Clytemnestra as a wronged woman when reading Aeschylus, but Casati has put flesh on the proposition and the story is told with a convincing progression towards its denouement.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!