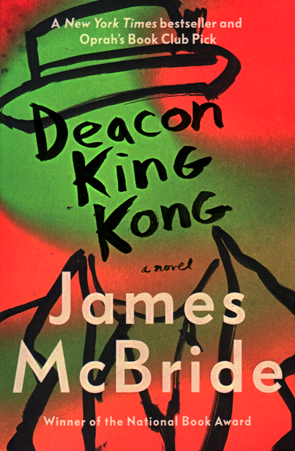

In the course of preparing to write this review I engaged in several forms of procrastination. I wrote an email, played solitaire, washed up, went for a walk and finally, I cut myself some cheese. It was this last, performed without thought when I had intended to walk to my study where my computer was already humming, that made me pause. Admittedly, I had had many thoughts about James McBride’s latest offering, but my dithering had been the result of my uncertainty as to how to begin to talk about the book. Deacon King Kong follows McBride’s historical drama, The Good Lord Bird, which is a postmodern tongue-in-cheek account of John Brown’s attempts to begin an uprising at Harper’s Ferry in 1859 which would lead to the abolition of slavery. Despite some quirky aspects to the novel, it had a serious point to make about race and America’s history. Deacon King Kong is something a bit different. I guess it is also historical fiction – it is set in the months after the first Lunar landing in 1969 – but its story is not specific to an historical event. Instead, McBride’s latest novel steers close to the farcical in some key moments, as it tells the story about the fallout of a shooting in the Causeway Housing Projects (otherwise known as ‘the Cause’), a fictionalised version of the area in which McBride, himself, grew up, in New York.

Deacon Cuffy Lambkin, known to everyone as Sportcoat, has just shot Deems Clemens, a young man he has previously mentored in baseball. Clemens has betrayed his substantial abilities as a pitcher and has taken to selling drugs, instead. Luckily for Clemens, Jethro ‘Jet’ Hartman, a young undercover cop, warns him just before Sportcoat gets his shot off, and instead of losing his life, Clemens only loses an ear. The strange thing is, that after the shooting Sportcoat seems to have no memory of having tried to take Clemens’s life, yet it was done openly in front of witnesses. Also strange is that Sportcoat is not arrested, nor does his community seem to fear him, even if his action remains mysterious. Bunch Moon, Clemens’s criminal boss, wants Sportcoat punished for the shooting – “Cut him a little. But not too hard” – and Sergent Kevin ‘Potts’ Mullen, only months away from retirement, wants to find Sportcoat, ostensibly because he knows he may be in danger. But Sister Gee and others associated with the Five Ends Baptist Church are vague about Sportcoat’s whereabouts, and Potts finds himself falling for Sister Gee, instead (not really a religious sister but a ‘sister’, as in someone in the community) as he tries to unravel the complications about Sportcoat’s identity and where he may be hidden.

There are elements to Deacon King Kong that make the tone of the book unusual. First, it has several disparate plot lines which we understand will somehow be shown to relate as we read. Second, the story is about the past and the ways the past affects the present moment. It’s about community and the uncertain possibilities, for good or bad. But it wavers between being a serious drama and moments that can only be described as farcical and hilarious, even if somewhat improbable.

Sportcoat has shot Clemens. Bunch Moon wants him punished. Meanwhile, Sportcoat is worried about the Christmas Club money that has gone missing since his wife, Hettie, died. Hettie’s body was retrieved from the harbour by Tommy Elefante, an old fashioned criminal from the original Italian immigrants of the area. Sportcoat now does gardening work for Elefante’s mother. And Elefante, feared for his propensity for violence but secretly desiring love, is approached by Driscoll Sturgess, otherwise known as the ‘Governor’, to help him find and ship a treasure worth a fortune to Europe. Sturgess knew Elefante’s father, a man of high principles, and is willing to let Elefante take the money for the item; enough money that he will never need to work again. Driving this story is a series of mysteries: why did Sportcoat shoot Clemens?; what is the mysterious connection between Elefante and Sturgess, as well as Elefante and the people of the Cause?; and where does all the cheese come from each month – presumably stolen – that Hot Sausage, Sportcoat’s friend, distributes to the people of the Cause from the basement of his building.

In short, McBride’s narrative is actually intriguing, as is his approach. A good part of one chapter is narrated from the perspective on an army of hormigas rojas asesinas, red ants accidentally imported from Columbia, that swarm into the buildings of the Cause annually in search of the cheese. The march of the ants is implacable and rapacious, a metaphor for the oppressive world that holds back black people from achieving their potential. Sister Gee reflects:

You worked, slaved, fought off the rats, the mice, the roaches, the ants, the Housing Authority, the cops, the muggers, and now the drug dealers […] all living the New York dream in the Cause Houses, within sight of the Statue of Liberty, a gigantic copper reminder that this city was a grinding factory that diced poor man’s dreams worse than any cotton gin or sugarcane field from the old country.

McBride’s narrative deconstructs the American Dream. The lives of black Americans are elided from the national discourse while the lives of white Americans contribute to the ‘American Myth’: “the white man’s reality lumping together like a giant, lopsided snowball”.

This seems like a realistic assessment of black history in America; at least it reflects many narratives told about African-American experience of life.

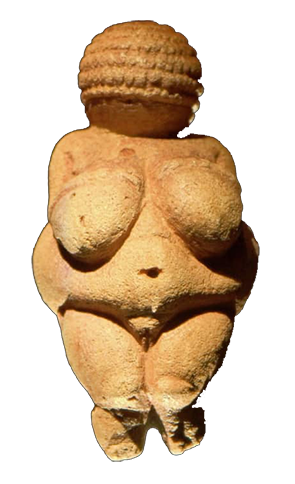

But this insight seems almost anomalous in McBride’s narrative. Because, instead of historical fiction, McBride seems to offer us an alternate history, as much as that appellation does not seem to fit the book. His use of the Venus of Willendorf in the story, for instance, assumes an entirely fictional provenance for the figure. And McBride’s New York may reflect some of the realities of the changing social and racial mix of areas like the Cause, but it does not entirely reflect the social realities of this period in the late 1960s, or even the experience of African-Americans, since. Call it what you will, an alternate history, or even a fairy tale if you like, there is a strange dissonance between Sister Gee’s social insight and the narrative direction McBride takes.

The story of Sportcoat, alone, is a good example. Sportcoat is a drunk. He ‘speaks’ to his dead wife daily, either in dreams or intoxicated delusions. His nickname – ‘Deacon King Kong’ – derives from the home brew called ‘King Kong’ made by his friend, Rufus Harley. Sportcoat is dependent on alcohol and his brain is mostly addled. That’s why he has difficulty remembering the shooting. As such we may regard him as an ingénue, since he appears to understand little about the implications of what he has done, and instead obsesses over the lost Christmas Club money, which has more immediate and understandable ramifications for him. McBride employs the well-known trope of the innocent who escapes retribution or circumstance when he tells us Sportcoat’s story. Like Forrest Gump who succeeds despite his limitations, the old woman from A Fish Called Wanda, who somehow avoids all Ken’s attempts to assassinate her, or the Road Runner avoiding the machinations of Wiley Coyote, Sportcoat’s ability to not only avoid Earl the hitman’s attempts to harm him, but to have those attempts turned back upon Earl, are hysterically funny, contrived and somewhat unbelievable. A scene in which Earl is accidentally electrocuted as he attempts to carry out his contract on Sportcoat, is so long-winded in the setup, that one can only imagine McBride took deliberate pleasure in the scene and Earl’s ineptitude: that he wanted us to see his sleight of hand.

These changes in tone, from realistic social commentary to high farce, suggest more than a wide tonal range. McBride dedicates the novel to ‘God’s People’, and his acknowledgement at the back of the book is a thanks to “the humble Redeemer who gives us rain, the snow, and all things in between.” By the end of the novel, we might have a pretty good notion about where the cheese comes from that is distributed each month to the people of the Cause, but despite evidence of any human agency Hettie insists to Sportcoat that “it was from Jesus” . The main characters are from the Five Ends Church, and most of them were instrumental in the establishment of the church, years before. This is a novel about people steeped in the hope of religious belief, set at a moment when heroin is taking over neighbourhoods. If we again look at it as an alternate history, just for a moment, we see it encourages us to not only ask questions about the progress of the plot as we read, but our reading raises other questions, implicitly. They seem to involve ‘what ifs’. What if prejudice could be overcome? What if we could understand our past and overcome personal animosity? What if, by a miracle, the social limitations placed on the black community was negated? By drawing together the various elements of his plot, through the unearthing of the interrelations of characters’ pasts, and by overcoming problems with a sense of decency and principle, McBride’s characters offer us a fairy tale that stands in juxtaposition to the social realities that undermine the American Dream for many poor and black communities: to that extent, it is a tale of hope. It results in a sometimes peculiar story, shifting between one set of values and circumstances and another, but it is highly entertaining and worth a read.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!