One of the most rousing and poignant moments of the Les Miserables musical, for me, comes in the second act when Eljoras leads his small group of student revolutionaries with the line, “They will come when we call.” It expresses the idealism and naivety of revolutionaries through the ages: that firmly held beliefs can lead to resolve and action; that adherence to belief is often blind to the indifference, fear or even resistance which might stymie the call to arms upon which the revolution has pinned its hopes.

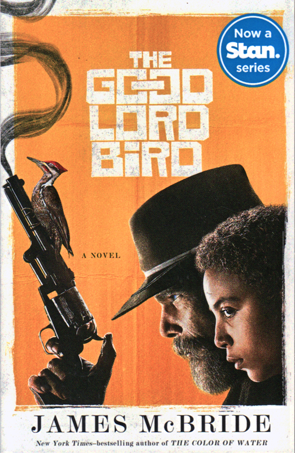

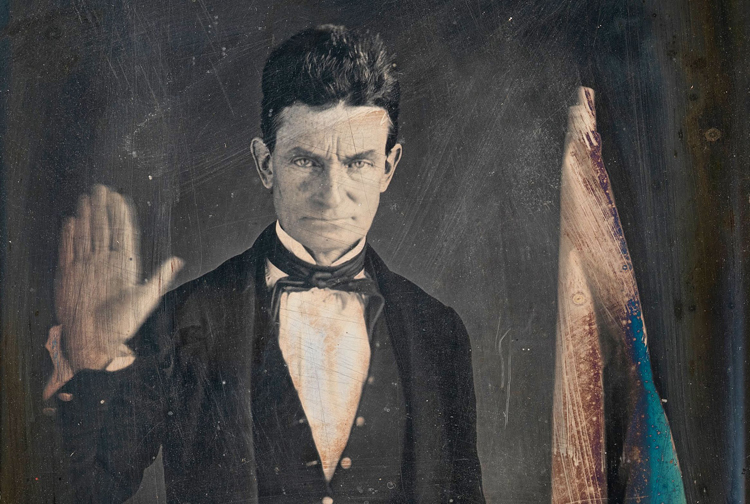

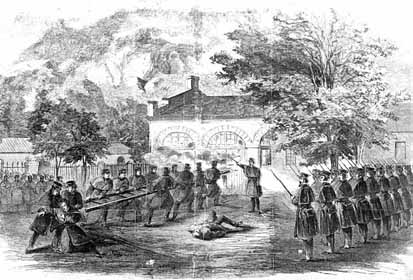

That’s basically The Good Lord Bird in a nutshell. James McBride’s novel about John Brown, the famous abolitionist who decides to fight slavery rather than just denounce it, culminates in Brown’s ill-fated attempt to take the armoury at Harper’s Ferry. Brown’s intention is that this action will be the catalyst to inspire support from the negro population - to hive the bees

as he puts it – and help arm them for a guerrilla war to end slavery. McBride tells the story of the raid and John Brown’s actions in the years leading to it through the eyes of a young negro boy, Henry Shackleton, otherwise known as ‘the Onion’ to John Brown, on account of Henry having mistakenly eaten Brown’s lucky onion when Brown shows it to him. The nickname, itself, is revealing, since Brown gives Henry this sobriquet in the belief that Henry is now imbued with John Brown’s luck: he has become John Brown’s lucky charm. Brown and his son, Frederick, also revere the feathers of the ‘Good Lord Bird’, a woodpecker.They say a feather from a Good Lord Bird’ll bring you understanding that’ll last your whole life,

Fred tells Henry, and explains they call it that because It’s so pretty that when man sees it, he says, ‘Good Lord.’

Frederick is a rather simple man without his father’s powerful intellect, but John Brown is also susceptible to superstitious belief, even self-deception. When Henry eats Brown’s good-luck onion Brown decides to divest himself of an array of other charms he has accumulated – cans, arrowheads, a pocketknife, even weevils – and give them to Henry, whom he hopes will in turn free himself of their influence as his faith in God grows. Brown also gives Henry a feather of the Good Lord Bird, a special token, but Brown warns him you ought not to believe too much in heathen things

, despite his own superstitious belief in Henry as a charm. Brown’s thinking, like most people’s, has its contradictions, except for his unwavering belief in God and the Bible, and his absolute resolution to end slavery. Past that he is likely to believe what he wants to believe. Brown takes Henry into his care after Henry’s father is accidentally killed in an altercation Brown engages in with Dutch Henry Sherman, Henry’s owner. But in a moment of confusion and misunderstanding, Brown mistakes Henry as a girl and thereafter calls him Henrietta. Henry, believing himself to be in the presence of a madman, and not wishing to stir trouble until he can effect his own escape, plays along, wearing a dress and adopting the airs of a young girl.

McBride’s narrative is witty and entertaining, as well as playful. Aspects of the narrative reminded me of George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman series: not just as a historical narrative, but for its erudition, its knowing winks to the reader and its likeable character with a secret identity. Flashman is the bully from Thomas Hughes’s Tom Brown’s School Days, now a member of the British army, always appearing at critical moments of 19th century British military and political history to play a critical role, even if he doesn’t mean to. Flashman’s secret is that he is a coward who only wants to bed women, yet somehow, he accidentally becomes the hero despite his best efforts. Henry’s secret is that he is a boy posing as a girl who wishes to escape, yet is somehow always drawn back to Brown and seen as an inspiration of loyalty and female bravery great enough to shame Brown’s men to action. Given that, along with his desire for a prostitute called Pie (and later Annie, John Brown’s own daughter) complicated by his female identity, how could we not like Henry and smile at his misfortunes?

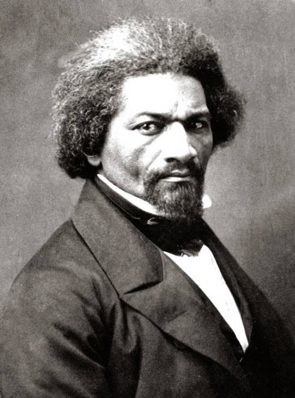

In fact, one of the funniest moments in the novel is at the expense of Frederick Douglas, king of the Negro People

, the famous negro abolitionist who declined to join Brown at the Harper’s Ferry insurrection, and who accepts Henry’s female identity. Douglas is lambasted for his living arrangements – he has two wives who each compete for attention – and is further lampooned in a scene worthy of a Carry On movie, Benny Hill, or Flashman, himself:

They know not you, Henrietta. They know you as property. They know not the spirit inside you that gives you your humanity. They care not the pounding of your silent and lustful heart, thirsting for freedom; your carnal nature, craving the wide, open spaces that they have procured for themselves. You’re but chattel to them, property, to be squeezed, used, savaged, and occupied.

Needless to say, Douglas is already squeezing and savaging

Henry as he derides the intentions of white people, forcing Henry to escape. Like Henry (like John Brown himself), Douglas is a man of contradictions and complications.

McBride plays fast and loose with the idea of identity and authenticity throughout the novel. For a start he adopts the common trope that the manuscript, told in Henry’s first-person vernacular, is a found text, a first full account of Brown and his men from a close witness. The manuscript has been found in a metal fireproof box hidden behind the pulpit of a church that has burned down. Charles Higgins, an amateur historian, wants the account given to an historical expert, but as readers we are in on the joke. The manuscript’s provenance is put into question by McBride’s wink and nod to the reader. Mr Higgins, the deacon of the church, is revealed to be despised by his wife - I’ll send your ass hooting and hollering out my damn door

- and has been given unfortunate epithets by his congregation: Mr Whopper

and Deacon Shimmy Wimmy

. How are we meant to take the manuscript’s provenance seriously after that?

Even minor characters are not always what they seem. Frederick Douglas is a philanderer. Sibonia, a slave held in the pen at Pikesville, affects madness, but is secretly planning an insurrection and is highly principled, fiercely defiant and intelligent. Hugh Forbes, paid a fortune to train Brown’s army, is nothing but a crook. And Henry, himself, feels his own incongruities: his desire to leave against his loyalty to John Brown; his desire to help against his own fear; his secret identity and his longing for authenticity.

I think that at the heart of these contradictions is the contradiction of America itself, founded upon a constitution that states all are free and equal, while a whole class of people are enslaved based upon their race. It’s the reason for Brown’s struggle and why he goes to Canada to convene a constitutional convention to address the legal issues of freedom and the problems of establishing a free state once his insurrection succeeds.

For Henry, personal contradictions are a product of the slave system, and are of nothing in comparison to it. Slavery arises from being black and race is all that matters. Personality and individuality are negated by the overarching principle of race, and elided by the needs or white society:

You just a nigger to him. A thing: like a dog or a shovel or a horse. Your needs and wants got no track, whether you is a girl or a boy, a woman or a man, or shy, or fat, or don’t eat biscuits, or can’t suffer the change of weather easily. What difference do it make? None to him, for you is living on the bottom rail.

The Good Lord Bird is a journey, from Henry’s first meeting with John Brown, to after the events at Harper’s Ferry. Much of the rhetoric against slavery comes from John Brown’s mouth, but Henry is also inspired by John Brown, and moves closer to Brown’s visionary thinking on the subject of slavery. McBride’s Henry speaks with authenticity, despite McBride’s post-modern playfulness. His narrative is engaging and entertaining, and as readers we watch the events at Harper Ferry unfold knowingly, yet we are still gripped by John Brown’s bravery and naivety and the unwitting mistakes that of Brown and his men. After John Brown’s capture, Victor Hugo, author of Les Miserables, warned of a possible civil war if Brown was executed, calling it an uncorrectable sin

and raised the paradox that one would see the assassination of Emancipation by Liberty itself

. The South, in fact, reorganised its militia system as a result of Brown’s raid, which was to form the basis of the later Confederate army. But as John Brown tells Henry, Sometimes bees don’t hive for years

, thereby allowing that something good was ultimately to come of John Brown’s actions.

The Good Lord Bird is highly readable and entertaining, and is worth a read.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!