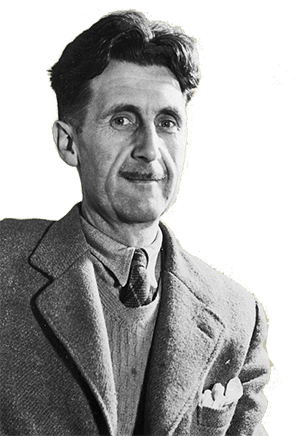

Coming Up for Air was George Orwell’s fourth novel, the last he had published before he wrote his final two most famous novels, Animal Farm and Nineteen-Eighty Four. Orwell had conceived of the idea for the novel at the end of 1937, after he had published Homage to Catalonia, which was an account of his experiences in the Spanish Civil War where he had been wounded by a sniper’s bullet in the neck. In December 1937, roughly seven months after he had received the wound, Orwell wrote about his new idea in a letter: “. . . it will be a novel, it will not be about politics, and it will be about a man who is having a holiday and trying to make a temporary escape from responsibility, public and private. The title I thought of is ‘Coming Up for Air’.”

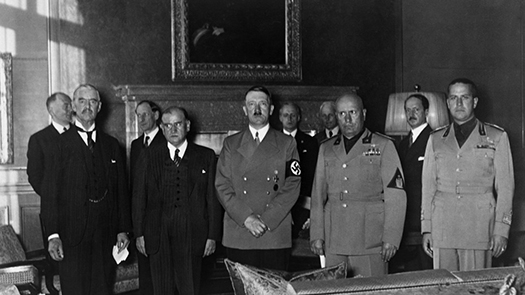

But before he could begin writing, Orwell faced another life threatening danger. He began coughing up blood and during March 1938 he was admitted to Preston Hall Sanatorium where it was suspected he was suffering from tuberculosis. Orwell only began writing the novel after he travelled with his wife, Eileen, to Morocco in September 1938 on the advice of his doctors – a warmer, drier climate – to aid his recovery. One can only speculate how the delay in writing may have affected the final novel. As it was written, it is more ambitious than Orwell’s initial description would suppose. During the period he wrote Coming Up for Air, war in Europe seemed more and more inevitable. Tensions had mounted in Europe during the beginning of Orwell’s period of recuperation in Morocco. The Munich crisis, named for the agreement signed by Germany, Great Britain and France, which ceded Czechoslovakia’s border regions and defences (the so-called Sudeten region) to Nazi Germany, occurred as Orwell began to write. Orwell’s biographer, Michael Sheldon, writes, “At times he felt almost as if he were in a race to finish the book before the war started. He knew that it could break out at any moment.”

It is these circumstances which seem to shape the novel, even though much of it is a reverie about the past, the period before the First World War, after which, Orwell’s protagonist feels, everything changed. This “man who is having a holiday”, George Bowling, returns to his old town of Lower Binfield where he used to fish as a boy, and discovers that the population has exploded: there has been housing developments everywhere; most of the businesses he knew have either disappeared or are now owned by someone else; a cemetery has been established on the outskirts of town; Binfield House, which was once surrounded by woodland, has become a mental home while its surrounds have become an enclave for the richer, more eccentric, members of the community; and the secret pool George had long dreamed of returning to, to catch its enormous fish, has been drained and turned into a rubbish pit.

It’s this hope, that George might return to Lower Binfield and secretly recapture his past, which holds the meaning of the title. The modern world has changed people. Now, there is style over substance, with American culture exemplifying the worst of the superficial popular culture George dislikes. George feels that life had contained, “a kind of vital juice that we’ve squirted away”, with “Nerves worn down to bits”. Modern life is a “dustbin”, but returning to Lower Binfield is a means by which George can return to the top and surmount life’s iniquities: that feeling of “Coming up for air!”

For want of a better word, the novel has a peculiar ‘feel’. I am talking about both structure and style. It begins as a conventional novel. George Bowling is forty-five years old, has become overweight and is receiving his first set of false teeth. Clearly, George’s best days are behind him. When he later meets Elsie, a girlfriend whom he lived with for a short time in Lower Binfield, he remarks upon the terrible changes time has wrought upon her appearance: “It’s frightening, the things that twenty-four years can do to a woman”. He describes her as a, “kind of soft lumpy cylinder, like a bag of meal.” Nevertheless, George reflects little upon the fact that Elsie fails to recognise him at all.

So, George is middle-aged and feeling the burden of married life and children. He fought in the first war and has returned to a life in which he is nothing special. But his job as an insurance salesman allows him to travel, and it is this, along with a secret windfall he has received from a bet on a horse race, which enables him to undertake his trip to Lower Binfield alone.

The peculiar ‘feel’ of this novel may be due to several aspects. First, we expect a contemporary tale of fiction as the novel opens, describing George’s home life and his new false teeth. But Coming Up for Air transforms quite early. George’s mind is suddenly returned to Lower Binfield thirty eight years ago after he sees a newspaper poster bearing the name of King Zog. It reminds him of a psalm sung in his church when he was a boy. It’s a very Proustian moment – like that moment in Swann’s Way when Marcel eats the Madeleine and his memories begin to suddenly unpack. Now, Coming Up for Air likewise becomes a semi-autobiographical reverie that reads more like a memoir.

But George’s reflections are not limited to his nostalgia and its terrible disappointment. It becomes evident that George is also a mouthpiece for the author, and at times he reflects upon issues that seem unusual for his character. He describes a lecture he and Hilda attend about Fascism. George’s feelings against the speaker, who seems to advocate hatred, are remarkably attuned to Orwell’s own stated positions. George’s fixation upon the coming war is also evidently Orwell speaking through his character, although some of the best parts of the novel are these pieces, when the narrative is raised above domestic mundanities or the musings upon how things used to be, and addresses the contemporary threat of Hitler and what war will mean. Of note is the insight George has in the middle of the lecture against fascism, that the speaker’s vision of defeating fascism is no less a fascist fantasy, itself, in which the speaker pictures himself, “smashing people’s faces in with a hammer. Fascist faces, of course.” It seems to anticipate one of Orwell’s most famous sentences from Nineteen-Eighty Four: “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – for ever.” And George’s estimations of the impact that the war will have and the ability of the British public to understand its implications feel more like the words of an essayist than an insurance salesman.

So, the novel feels more like a hybrid between fiction, memoir and essay. The circumstances around the period in which it is being written seem to have reshaped the story, too. George’s story, “not about politics”, is indeed political. The narrative first draws George imaginatively back to his past, then shows that that past no longer exists. Lower Binfield has not only been transformed socially, but it has become a part of the gearing up for war which is driving England. The Truefitt Stockings factory has been transformed into a munitions factory, and when one of its bombs is accidently dropped upon Lower Binfield during practice manoeuvres, it is ominous that the devastation caused by the bomb is deemed to be only “disappointing”.

Like the two wars, there is an implicit parallelism in the structure of the novel. The return to Lower Binfield reveals the past to be gone, but the constant anticipation of a future war implies that the present will be just as ephemeral:

I’ve enough sense to see that the old life we’re used to is being sawn off at the roots. I can feel it happening. I can see the war that’s coming and I can see the after-war, the food-queues and the secret police and the loudspeakers telling you what to think.

The novel indulges in terrifying vignettes, of children in gas masks, of machine guns rattling out of windows and even the dismemberment of war. George tells us,

We’re all on the burning deck and nobody knows it except me. I look at the dumb-bell faces streaming past. Like turkeys in November, I thought. Not a notion of what’s coming to them.

George is channelling Orwell directly, it seems. A similar sentiment is expressed by Orwell in a letter to essayist and novelist, Jack Common, in January 1939, five months before the book was published:

It’s getting harder and harder for the English public. I suppose 50 percent of them knew whereabouts Austria was and about 20 percent knew where Czechoslovakia was, but where is the Ukraine? . . . The only people who can really keep up with affairs nowadays are philatelists.

The whole novel is a strange mixed bag. On the one hand we understand that George’s attempt to capture his past is doomed to fail. It’s foreshadowed by the developments he complains about in the suburb he and Hilda currently live. George’s attitudes to progress are ambivalent, both accepting its need and railing against its reality, because, in essence, it is a mirror to his own aging body he finds difficult to accept. He still wants to think there are “plenty of good times ahead, and the notion of myself as a kind of tame dairy-cow for a lot of women and kids to chase up and down doesn’t appeal to me.” Modern readers would identify a certain level of misogyny in George’s statements, born from his dissatisfaction with his life. In this present time he is older and unattractive, and he lives with a wife he finds controlling and unlovable and with two children whose sole connection he feels is to have been brought into the world as his children.

There is enough material in that scenario to have potentially made Coming Up for Air a subtle character study in nostalgia and home life. Then there is this other aspect of the novel, its meditation on the coming war and the implications of that, which does not always smoothly dovetail into the plot Orwell initially conceived. Each aspect of the novel is compelling, but I had the feeling that Orwell might have written more convincingly had he abandoned the pretence of George Fowling. But his character is a decade older than Orwell. There is still purpose here. The age difference allows Orwell to place George as a combatant in the First World War, and with a life prior to that. That’s the uneasy marriage Orwell is trying to make, which requires a fictionalising of the self. I guess what I’m trying to say is that Coming Up for Air has a peculiar feel. But knowing that before reading would probably have made the novel less jarring. Because its separate elements are still engrossing. I loved the nostalgic elegy for Lower Binfield, and I was fascinated by the glimpses of later Orwellian novels too. This makes Coming Up for Air a book still very much worth reading, and easy to enjoy, despite that it fails to successfully integrate its parts.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!