[Read More]

In the summer of 1946 while hiking on the island of Jura, an island off the west coast of Scotland, I hurt my ankle and spent a week resting on a farm. As the leg got stronger I began to hobble around the surrounding countryside, which was bleak and dry owing to a drought. One day I came upon a very tall, very thin, very shabby man carrying a gun. We stopped to talk and, in his case, to smoke a home-made cigarette. He had a gaunt and lined face, with dark hair and a scrubby moustache running across his top lip, and looked to be in his late fifties. For clothes he had on a pair of brown corduroy trousers, very baggy, a black shirt, and a very old Harris tweed jacket which matched the colour of the landscape. It was George Orwell, who had become mildly famous since the publication of Animal Farm in the previous year, and he was 46. He was living in a farmhouse called Barnhill and, on discovering that I was familiar with most of his work, invited me back for high tea, later that day.

When I arrived, Orwell fussed around organising an elaborate tea, with Scottish oat cakes, kippers and toast, Gentlemen’s Relish, Cooper’s Oxford marmalade, and several jams. It was a delightful cross between cuisine and stamp-collecting. He made the tea himself, in a large earthenware pot, and told me there were eleven rules for this process.

“On perhaps two of them there would be pretty general agreement,” he told me with a self-deprecating smile that faded quickly as he became involved in the subject, “but at least four others are acutely controversial.” His voice was flat and almost toneless, a result of the damage caused by the bullet which went through his neck in Spain in 1937.

[Read More]

“The pot should be warmed beforehand,” he told me urgently. “This is better done by placing it on the hob than by the usual method of swilling it out with hot water.”

“Why – ”

“The tea should be strong. I maintain that one strong cup of tea is better than 20 weak ones. All true tea-lovers not only like their tea strong, but like it a little stronger with each year that passes. One should take teapot to the kettle and not the other way about. The water should be actually boiling at the moment of impact, which means that one should keep it on the flame while one pours.”

He set out the cups and saucers as he was talking, and then began to pour the tea. Trying to enter into the spirit of the thing, I remarked that he had not yet put in the milk.

“One should pour tea into the cup first,” he urged. “This is one of the most controversial points of all. The milk-first school can bring forward some fairly strong arguments, but I maintain that my own argument is unanswerable. This is that, by putting the tea in first and then stirring as one pours, one can exactly regulate the amount of milk, whereas one is liable to put in too much milk if one does it the other way round.”

At the end of tea, Orwell stood up suddenly and announced that he was going up to his room to do some work. He looked at me with what I thought was a fleeting expression of guilt, and invited me to come out in his boat the next day. Then he was gone.

[Read More]

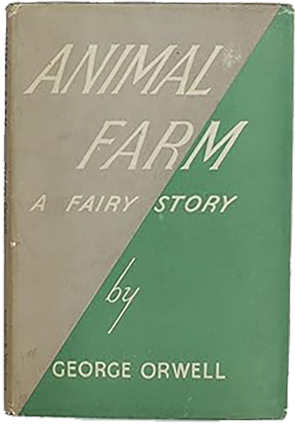

Animal Farm had been turned down by several publishers before being taken by Secker and Warburg. In at least one case the manuscript was sent to the Ministry of Information, which suggested it would not be in the national interest if a book insulting Britain’s great ally, Stalin, were to be published. T.S. Eliot at Faber and Faber wrote to its author that “we have no conviction . . . that this is the right point of view from which to criticize the political situation at the present time.” Fortunately, once it was published the book was warmly received and sold well, with a second printing soon being required. By the time I met Orwell, his reputation had extended well beyond intellectual circles.

The next evening I went with him in his small rowing boat to check the lobster pots. On the way to the beach we met a farmer and his family, and once we were on the water Orwell began to talk about the English common people. Their characteristics, he opined, were “artistic insensibility, gentleness, respect for legality, suspicion of foreigners, sentimentality about animals, hypocrisy, exaggerated class distinctions, and an obsession with sport.” I asked why they were so xenophobic. “The peculiarities of the English language make it almost impossible for anyone who has left school at fourteen to learn a foreign language,” he explained. “The English language has two outstanding characteristics to which most of its minor oddities can be finally traced. These are a very large vocabulary and simplicity of grammar. Every person in every tense of such a verb as [to kill] can be expressed in only about thirty words including the pronouns, or about forty if one includes the second person singular. The corresponding number in, for instance, French would be somewhere near two hundred.” So, he said, “the English are very poor linguists. Their own language is grammatically so simple that unless they have gone through the discipline of learning a foreign language in childhood, they are often quite unable to grasp what is meant by gender, person, and case. In the French Foreign Legion, for instance, the British and American legionaries seldom rise out of the ranks, because they cannot learn French, whereas a German learns French in a few months.”

He had a theory that the English of literary and other educated people — so-called standard English — “has grown anaemic because for long past it has not been reinvigorated from below. The people likeliest to use simple concrete language, and to think of metaphors that really call up a visual image, are those who are in contact with physical reality. A useful word like [bottleneck], for instance, would be most likely to occur to someone used to dealing with conveyor belts. The vitality of English depends on a steady supply of images of this kind. It follows that language, at any rate the English language, suffers when the educated classes lose touch with the manual workers. As things are at present, nearly every Englishman, whatever his origins, feels the working-class manner of speech, and even working-class idioms, to be inferior.”

The weather was very warm, the sea gentle. I rowed on, saying nothing, while Orwell explained aspects of the shoreline to me with the air of a geography teacher conducting a school excursion. To change the subject, I asked him about the English enthusiasm for pets.

“Britain today has a million and a half less children than in 1914 and a million and a half more dogs,” he said. “Perhaps the most horrible spectacles in England are the Dogs’ Cemeteries in Kensington Gardens, at Stoke Poges (it actually adjoins the churchyard where Gray wrote his famous ‘Elegy’) and at various other places. But there were also the Animals ARP Centres [during the Blitz], with miniature stretchers for cats . . .” Orwell shivered, paused for a moment, and went off on a tangent. “Dislike of hysteria and ‘fuss’, admiration for stubbornness, are all but universal in England, being shared by everyone except the intelligentsia. Millions of English people willingly accept as their national emblem the bulldog, an animal noted for its obstinacy, ugliness, and impenetrable stupidity.” He pulled up a pot, spilling water all over his trousers. “A profound, almost unconscious patriotism and an inability to think logically are the abiding features of the English character, traceable in English literature from Shakespeare onwards.”

The next day Orwell was going to the mainland, and I was to recommence my holiday. We shook hands on the beach and he tried to give me one of his lobsters, which I declined as gracefully as I could.

“Are you writing anything at the moment?” I asked.

“Actually I have at last started my novel about the future.”

“A novel about the future? Sounds interesting.”

“I’ve only done about fifty pages and God knows when it will be finished.”

“Well, goodbye.”

He stood on the rocks, looking at the ground, then shook his head, smiled at me and strode off, no doubt thinking about his novel about the future.

Back in London I conceived the idea of doing an article about Orwell. During the winter I wrote to him and he agreed. I sought for people who knew him and found that many of them had something in common — they had no idea of the identity of each other. Whereas most of us have a fairly cohesive circle of friends, Orwell seemed all his adult life to have had pockets of friends scattered here and there, isolated from each other geographically, politically and socially. I later came to the conclusion that this helped him maintain his independent perspective — having to listen to widely diverging views all the time perhaps forced him to work out where he himself stood.

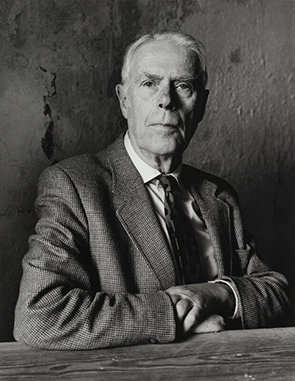

One surprising friend was Anthony Powell, admittedly an old Etonian, like Orwell, but also a conservative. Powell recalled that when Orwell and he met for the first time as adults he was wearing a fairly pretentious uniform. Aware of Orwell’s reputation as a wild socialist, he was concerned at what effect this apparel might have on him.

“Do your trousers strap under the foot?” were Orwell’s first words.

“Yes.”

“That’s really the important thing.”

“Of course.”

“You agree?”

“Naturally.”

“I used to wear ones that strapped under the boot myself.”

“In Burma?”

“You knew I was in the police there? Those straps under the foot give you a feeling like nothing else in life.”

Orwell’s wife, Eileen, had died the previous year in the course of what was expected to be a routine operation. In the next twelve months he proposed to a number of women and was turned down by all of them. During this time an American publisher was finally found for Animal Farm. As many as twelve companies were reported to have turned it down; American authorities in Munich seized 1,500 of the Ukranian edition of the book, and handed them over to the Soviets.

In 1947 I returned to Jura for my summer holidays. Earlier in the year it had been dry — there had been six weeks without rain — but the drought was now over. I found Orwell ill, with some chest problem, but cheerful. He had finished over a third of his novel about the future and cheerfully recounted several accidents that had occurred. In one, Orwell, who had obtained a motor boat, had misread the tide chart and taken it into a dangerous patch of water, with whirlpools, where it had capsized. Orwell, his young son Richard and two guests escaped drowning more by luck than anything else.

I had several long and slightly formal conversations with Orwell. I started by asking him about his early life.

[Read More]

“How old are you?”

“I was born in 1903 at Motihari, Bengal, the second child of an Anglo-Indian family. I was the middle child of three, but there was a gap of five years on either side. For this and other reasons I was somewhat lonely, and I soon developed disagreeable mannerisms which made me unpopular throughout my schooldays. I had the lonely child’s habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons. As a very small child I used to imagine that I was, say, Robin Hood, and picture myself as the hero of thrilling adventures, but quite soon my ‘story’ ceased to be narcissistic in a crude way and became more and more a mere description of what I was doing and the things I saw.”

“When did you know you wanted to be a writer?”

“From a very early age, perhaps the age of five or six. Between the ages of about seventeen and twenty-four I tried to abandon this idea, but I did so with the consciousness that I was outraging my true nature and that sooner or later I should have to settle down and write books.”

“Why do you write?”

“All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the bottom of their motives lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.”

“And yet you’ve produced a lot, haven’t you?”

“Even at the periods when I was working ten hours a day on a book, or turning out four or five articles a week, I have never been able to get away from this neurotic feeling, that I was wasting time. I can never get any sense of achievement out of the work that is actually in progress, because it always goes slower than I intend, and in any case I feel that a book or even an article does not exist until it is finished. But as soon as a book is finished, I begin, actually from the next day, worrying because the next one is not begun, and am haunted by the fear that there will never be a next one.”

“But surely you must be reassured by looking back at everything you’ve produced already?”

Orwell laughed ruefully. “It simply gives me the feeling that I once had an industriousness and a fertility which I have now lost.”

“Education?”

“I was educated at Eton as I had been lucky enough to win a scholarship, but I did no work there and learned very little. I served with the Imperial Police in Burma. I gave it up partly because the climate had ruined my health, partly because I already had vague ideas of writing books, but mainly because I could not go on any longer serving an imperialism which I had come to regard as very largely a racket.”

“Burma made you, in a sense, didn't it?”

“Anyone able to hold a pen can write a fairly good novel of the unpretentious kind, if only at some period of his life he has managed to escape from literary society. There is no lack nowadays of clever writers; the trouble is that such writers are so cut off from the life of their time as to be unable to write about ordinary people. A “distinguished” modern novel almost always has some kind of artist or near-artist as its hero.”

I mean no disrespect of George Orwell when I say that his reputation as the greatest independent political and social writer of our time demonstrates how easy it should be to be independent. He was simply a socialist who criticised the bad things in socialism, which, at least in theory, you would imagine an easy trick to pull off. That Orwell achieved the trick in practice should be unremarkable. It is not, because so few others have done it. Much of the fascination of Orwell, then, lies in wondering why he did something apparently so easy which the rest of us, no matter how intelligent and imaginative, cannot do. The reason why this is of interest, of course, is because the rest of us, despite the orthodoxies of our own lives, have some instinctual awareness that what Orwell has done is very much worth doing.

My theory is so crude that I might as well throw it in your lap right away: for an English writer, Orwell had an unusual upbringing. I am thinking of the time between his birth and his return from Burma, at the age of 24, in 1927. I don’t pretend what happened in these years explains many important things about him, such as why he became a writer in the first place, but then I don’t believe such things are capable of explanation. But his upbringing provided him with a body of unusual experience which gave him (compared with other writers) an independent imagination. The crux of the matter was his decision to join the Burmese police force instead of going to Oxford. Until that moment he had led the life of a typical member of the English lower-upper-middle class, at Eton and other schools that were also attended by future writers such as Anthony Powell, Cyril Connolly, Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh. Unlike most of these people, he was a scholarship boy, therefore something of an outsider. But what really mattered was that they all went on to Oxford and he did not.

[Read More]

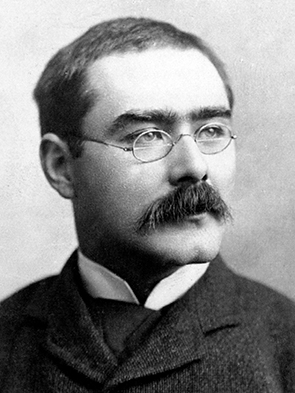

If what he did not do was important, what he did instead was perhaps even more so. The decision to join the Burmese police was an obvious one — his family could not afford to send him to university. His father had served in Burma and there were contacts there, including his maternal grandmother who still lived in Mandalay. He could not enter the Imperial Civil Service because he had not been to university, and of the other services the police was perhaps the most interesting. But however obvious it was for Eric Blair to go to Burma in 1922, the fact that George Orwell the great writer went to Burma is extraordinary. Who of all England’s leading writers in several centuries of empire had a similar experience? Only Kipling. This, almost certainly, is why Orwell can be so appreciative of Kipling. “I worshipped Kipling at thirteen,” he said, “loathed him at seventeen, enjoyed him at twenty, despised him at twenty-five, and now again rather admire him.” So much so that when Orwell speaks of Kipling he is sometimes, one suspects, speaking of himself.

“Because he identifies himself with the official class, he does possess one thing which ‘enlightened’ people seldom or never possess,” Orwell said slowly, “and that is a sense of responsibility. He identified himself with the ruling power and not with the opposition. In a gifted writer this seems to us strange and even disgusting, but it did have the advantage of giving Kipling a certain grip on reality. The ruling power is always faced with the question, ‘In such and such circumstances, what would you [do]?’ whereas the opposition is not obliged to take responsibility or make any real decisions. The nineteenth-century Anglo-Indians, to name the least sympathetic of his idols, were at any rate people who did things. It may be that all they did was evil, but they changed the face of the earth, whereas they could have achieved nothing, could not have maintained themselves in power for a single week, if the normal Anglo-Indian outlook had been that of, say, E.M. Forster.”

Now to most writers, and certainly most socialist writers, the idea that there is anything admirable in ‘doing things’ is anathema. The whole tide of modern writing is in the direction of passive experience, of a narrow sense of ‘being’, certainly not ‘doing’. I suspect that it is Orwell’s fondness for action, and the contemplation of action, which actually made him a political writer — as an imaginative writer he simply could not, in the England of the 1930s, have tackled the themes of action to which he is drawn.

So how did Kipling come to have his experience in the east? Said Orwell: “Much in his development is traceable to his having been born in India and having left school early. With a slightly different background he might have been a good novelist or a superlative writer of music-hall songs.” (Ah, George!) “He travelled very widely while he was still a young man, and some streak in him that may have been partly neurotic led him to prefer the active man to the sensitive man. Civilized men do not readily move away from the centres of civilization. It took a very improbable combination of circumstances to produce Kipling’s [work].”

It is, I think, impossible not to see Orwell himself in this description of Kipling. For over five years in Burma he sided with the ruling power and had to make decisions on what he would [do], decisions sometimes of life and death. “In Moulmein in Lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people,” Orwell said, “the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me.” This, when he returned to England and began the struggle to become a writer, gave him a body of experience unique among his contemporary men of letters, and unusual enough among writers in general. It gave him a centre, perhaps, a sense of common sense that never deserted him. And also, perhaps, a taste for being reviled.

It appears that in Burma, Orwell was viewed by other English people as a book-reading eccentric but no worse. Only gradually did he turn against his fellows.

“In Burma I listened to racial theories which were less brutal than Hitler’s theories about the Jews,” he said, “but certainly not less idiotic. I often heard it asserted, for instance, that no white man can sit on his heels in the same attitude as an oriental — the attitude, incidentally, in which coal miners sit when they eat their dinners at the pit.” Whether such opinions worried Orwell at the time is uncertain; as the last example shows, his memories seem usually to be selected because of their relevance to subsequent experience and ideas.

What is clear is that for a sensitive young man the whole thing must have been an ordeal. He was mixing with English people who were simply not like himself — they were those he has called, when talking of Kipling, ‘active’ rather than ‘sensitive’ men. He further recalls that “most of the white men in Burma were not the type who in England would be called ‘gentlemen’.” He did not forge any close relationship with the native Burmese, who in fact contributed to his sense of uneasiness. “In the end the sneering yellow faces of young men that met me everywhere, the insults hooted after me when I was at a safe distance, got badly on my nerves,” he says of his time at Moulmein.

Many people have quit the East for reasons of temperament. The fact that Orwell transformed this into a political rejection is of course a vital part of his development, and memories of his Eastern experience continued to be important to him throughout his life. “All left-wing parties in the highly industrialized countries are at bottom a sham,” he told me, “because they make it their business to fight against something which they do not really wish to destroy. They have internationalist aims, and at the same time they struggle to keep up a standard of life with which those aims are incompatible. We all live by robbing Asiatic coolies, and those of us who are ‘enlightened’ all maintain that those coolies ought to be set free; but our standard of living, and hence our ‘enlightenment’, demands that the robbery shall continue.”

As a structural criticism of socialism this is perceptive, but as a criticism of socialists it is merely bilious. It is also confusing: how then could Orwell justify his own years as a socialist? There is no apparent answer. What the words do suggest is that Orwell’s Eastern experience was still gnawing at him, some of its implications still unresolved decades later. Writers need this sort of confusion deep within them. Usually it is provided by their family, but Orwell came from a family which was both short on passion and long on stability and loyalty. For Orwell the writer, perhaps Burma provided that unhappy youthful experience that neither his family nor (despite his claims to the contrary) his schools had been able to give him.

[Read More]

Soon after returning to England, Orwell began his bizarre period of tramping, during which he donned fancy dress and slept in doss houses for periods of between one night and several weeks. He has acknowledged the ridiculousness of this as a method of getting closer to the working class: “I knew nothing about working class conditions, I did not know the essential fact that ‘respectable’ poverty is always the worse. My mind turned immediately towards the extreme cases, the social outcasts: tramps, beggars, criminals, prostitutes. These were ‘the lowest of the low’, and these were the people with whom I wanted to get into contact. What I profoundly wanted, at that time, was to find some way of getting out of the respectable world altogether.” This tendency towards the picturesque was to colour all Orwell’s social reporting, and to affect the accuracy of the picture of working class life given in The Road To Wigan Pier when it was published ten years later.

Having said that, it must be stressed that Orwell’s attempts to get to know his subject were noble, and possibly unique for a writer of his generation. Most English writers, including most socialist writers, are sensitive and middle class, and the discomfit of moving out of their own class is too much to contemplate. Orwell could do it because, after his recent experiences in Burma, he was used to being alone and to physical discomfit. And of course he had the motivation, the need to get out of ‘the respectable world’ which so few others of his class seem to have felt. He saw his need to get down among the lost as a form of penance. “Once I had been among them and accepted by them,” he has written, “I should have touched bottom, and — this is what I felt: I was aware even then that it was irrational — part of my guilt would drop from me.”

It is difficult to see how else he could have done this in a society where class counts for so much — had he tried to live among the working class, his accent would have isolated him. But, as he has pointed out, with tramps this was no problem.

[Read More]

[Read More]

[Read More]

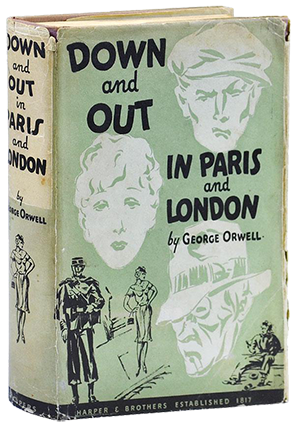

There was also a literary model. In 1902 Jack London had slept in the slums of the East End to write The People Of The Abyss, a book Orwell read at school. In 1928-29 Orwell lived in Paris, writing and working, and failed to publish any of his literary productions. It was perhaps the example of London’s book that encouraged him to turn his experiences into Down and Out In Paris And London, his first book, published in 1933. It was a strange sort of book for an old Etonian to write — in 1931 Anthony Powell had published his clever novel, Afternoon Men, and Graham Greene entered the same general field with Stamboul Train. These were the sorts of books English writers wrote, and for many years Orwell was to struggle to produce just such novels, even though the results were not much good. The decision to write what are basically documentaries was therefore highly unusual, and is central to Orwell’s achievement, as books like The Road to Wigan Pier and Homage To Catalonia are (by general consent) superior to his conventional novels. Why he made the decision we may never know, and yet, given the sort of life he was leading at the time, and the example of Jack London, it may have seemed to him simply the ‘natural’ next step in his career, given his lack of success with more conventional literary efforts.

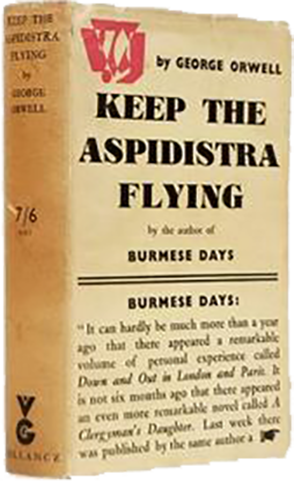

After Down and Out was published to modest success, Orwell laboured for several years, working by day as a schoolteacher or bookshop assistant, and in his spare time writing the unsuccessful novels: Burmese Days (1934), A Clergyman's Daughter (1935), and Keep The Aspidistra Flying (1936). These, together with Coming Up for Air (1939) might be considered a waste of his time, but had he not kept his hand in as a writer of fiction, it is unlikely we would ever have seen his best and most famous book, Animal Farm, such an unusual mixture of fiction and politics.

* * *

Orwell is a bully. His habit of claiming to speak for the people (“Take for instance the fact that all sensitive people are revolted by industrialism and its products”) reminds one of the worst sort of socialist ranter. His extremism should be absurd (“People know that in some way or another ‘progress’ is a swindle”) but it is strangely refreshing. The only reason I can think of to explain this is that we all tire of real life at times — and particularly those parts of it about which we are sick of hearing verbose nonsense — and are vulnerable to the charms of the straight talker. Hence, dare I say it, the appeal of fascism. Orwell is more attractive when he makes an absurd statement which nevertheless contains a half-truth never spoken before. When we were out in the boat he said: “Who has not felt when talking to a Czech, a Pole — to any central European, but above all to a German or a German Jew — ‘How superior their minds are to ours, after all!’ And who has not followed this up a few minutes later with the complementary thought: ‘But unfortunately they are all mad?’”

As one would expect from someone with extremist tendencies, Orwell’s predictions have not always been right. In June 1940 he wrote a letter to Time and Tide which began with the declaration ‘It is almost certain that England will be invaded within the next few days or weeks’ and went on to urge that the population be armed immediately with hand grenades and shotguns, and urged that the brewers’ names on the front of pubs be painted over as ‘Most of these are confined to a fairly small area, and the Germans are probably methodical enough to know this.’ Fortunately England was not invaded. Of more interest is his complete turnaround on the subject of pacifism. Not long before the war he wrote: ‘If one collaborates with a capitalist-imperialist government in a struggle ‘against Fascism,’ ie, against a rival imperialism, one is simply letting Fascism in by the back door’. Yet by 1940 he was writing that the ‘soft-boiled intellectuals’ who were ‘pointing out that democracy and fascism are the same thing etc depress me horribly’.

On my last day on Jura, our interviews finished, I dropped in to say goodbye. Of course Orwell made tea, and then we went for a walk, taking in his vegetable garden and the tent he had erected near the house, where he slept at night to get as much fresh air as he could. His lungs were in poor shape. Our talk was mainly idle, but there was one thing he said which puzzled me, a rare acknowledgement of the spiritual dimension of life, which was so chilling — and yet spoken in an offhand way — that it is worth ending on.

“Which writers do you enjoy?”

“Shakespeare, Swift, Fielding, Dickens, Charles Reade, Samuel Butler, Zola, Flaubert and, among modern writers, James Joyce, T.S. Eliot and D.H. Lawrence.”

I asked what it was he admired in a writer, and he talked a little of the horrors of capitalism and the waning of Christianity in the nineteenth century. “Consequently there was a long period during which nearly every thinking man was a rebel,” he said. “Literature was largely the literature of revolt or of disintegration. Gibbon, Voltaire, Rousseau, Shelley, Byron, Dickens, Stendhal, Samuel Butler, Ibsen, Zola, Flaubert, Shaw, Joyce — in one way or another they are all of them destroyers, wreckers, saboteurs. For two hundred years we sawed and sawed and sawed at the branch we were sitting on. And in the end, much more suddenly than anyone had foreseen, our efforts were rewarded, and down we came. But unfortunately there had been a little mistake. The thing at the bottom was not a bed of roses at all, it was a cesspool full of barbed wire.”

“You’re thinking particularly of Germany and the USSR in the 1930s?”

“It is as though in the space of ten years we slid back into the Stone Age. Human types supposedly extinct for centuries, the dancing dervish, the robber chieftan, the Grand Inquisitor, have suddenly reappeared, not as inmates of lunatic asylums, but as the masters of the world.”

“Would it have helped had we not lost religion?”

Orwell answered almost absentmindedly, looking at a hawk flying high above us. “It was absolutely necessary that the soul should be cut away. By the nineteenth century it was already in essence a lie, a semi-conscious device for keeping the rich rich and the poor poor . . .”

“And yet?”

“It appears that amputation of the soul [isn't] just a simple surgical job, like having your appendix out,” he concluded. “The wound has a tendency to go septic.”

[Read More]

[Read More]

Comments

No one has commented yet. Be the first!