Agamemnon

The Libation Bearers

The Eumenides

- Category:Play, Mythology

- Date Read:14 February 2025

- Year Published:1975 (458 BCE)

- Pages:335 (including introduction and notes)

Aeschylus’ Oresteia is the only dramatic Greek tragic trilogy that has survived, and it is comprised of three of only seven plays by Aeschylus that remain out of the nearly ninety plays he is believed to have written: Agamemnon, which dramatizes the murder of the Argive king upon his return from the Trojan War by his wife, Clytemnestra; The Libation Bearers, the story of the return of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra’s son, Orestes, to Argos to avenge the death of his father; and The Eumenides, in which the trilogy culminates with the trial of Orestes and the permanent establishment of an Athenian trial court.

I have included a summary of each of the three plays at the end of this review. Reading them should give you a pretty good idea of what these plays are about. Click here to skip to the summaries …

The Athenian Century

The Oresteia was written during Athens’ most consequential century of the ancient period, and the plays are better appreciated with some understanding of the cultural and historical moment that produced them. The Oresteia won first prize in 458 BCE at the Dionysia, an annual Athenian festival held in honour of the god Dionysus. This was a period of cultural, economic and political growth after Athens, along with other Greek city states, had defended Greece from attacks mounted by the Persian Empire. By now, Athens was proudly immersed in its democratic political experiment. From the perspective of modern readers, the democracy may seem limited. Athens had slaves and women were largely under the authority of their family or husband. Only free male citizens could vote. But it was truly experimental in an age when kings, tyrants or some form of oligarchy was the norm. For fifth century Athenians, their recent history and the innovations they had made in government were a source of pride. Aeschylus’ own play, The Persians, (also a winner of the Dionysia in 472 BCE) neatly exemplifies this. Athens, with Sparta’s help, had overthrown its tyrant, Hippias, in 510 BCE, and had formed a democratic government after it in turn overthrew the aristocratic oligarchy that succeeded Hippias. Meanwhile, Hippias had ingratiated himself with the Persian court, and with the support of the Persian king, Darius, he hoped to be reinstated. Hippias helped lead Darius’ ill-fated expedition against mainland Greece in 490 BCE, which was famously thwarted by Athenian and Plateaen forces at the Battle of Marathon. Ten years later, Darius’ son, Xerxes, led an even greater force across the Hellespont to conquer Greece. Greek resistance comprised of almost thirty states under the leadership of Sparta and Athens. Athens’ role in the war was lauded by writers like Aeschylus. The Athenians largely abandoned their city in a strategic move, leaving only a small defence. The Persians invaded the city, taking over the Acropolis and destroying temples. The Parthenon, which is the largest temple remaining atop the Acropolis, was constructed as part of a rebuilding program after the Persian invasion.

It is apparent in Aeschylus’ play, The Persians, that he is not averse to crowd-pleasing propaganda. The play recounts the defeat of the Persian fleet at Salamis, as told to Atossa, Xerxes’ mother, who anxiously awaits news of the engagement. The straits of Salamis had been Athens’ fallback position after abandoning their city. As the Messenger feeds Atossa more and more bad news, the Greek victory is largely attributed to Athenian leadership, its democratic institutions, its superior fighting techniques and its triremes. Xerxes’ Messenger tells Atossa that despite the lack of a permanent leader, the Athenian democracy is vibrant and strong enough to resist their overwhelming force. Athens is more than just a place. It is its people. On the Persian side, a number of factors are attributed to the defeat: Xerxes had offended the gods by building a bridge of boats across the Hellespont over which he marched his army. And his whole enterprise was hubristic, a moral failing in Athenian eyes (although it is evident that the play acts as a warning, too, against Athenian expansion and national pride after the war.) However, on the whole, the play is a celebration of the victory, and a vindication of the Athenian political experiment.

This is some of the context in which Aeschylus produces The Oresteia. The Oresteia is a grim tale of murder and matricide, but in the end, it is also a celebration of Athenian justice and Athens’ cultural and economic prosperity. To end the trilogy at this juncture seems like a large leap from the beginnings of the story, the Trojan War, and even further back, to a history of murder, even cannibalism, in the Atreides family. But The Oresteia can be read as an origin story, if you will. Remember, Virgil’s poetic account of the founding of Rome, The Aeneid, begins with the final moments of the Trojan War, too: the Trojan horse, the death of Priam and the fall of the city. Like Virgil, Aeschylus’ story evolves: in this case, from the point when Agamemnon first makes a fateful decision that has dire consequences: to sacrifice Iphigenia, his daughter, to appease the gods.

The Death of Iphigenia

The thing about any account of the events of the Trojan War is where to start and where to end. The death of Iphigenia is really the backstory of The Oresteia, but the play’s context extends into the past even further than that. Because, to understand Aeschylus’ play is to also place it within a history of intergenerational revenge. Aeschylus could presume that his audience had a working familiarity with the stories upon which his play is based, forming the backstory. For one thing, Greek myth has a tradition of fathers eating their young. Tantalus (from whom we get our word ‘tantalise’) is great-grandfather to Agamemnon and Menelaus. He famously serves his own son, Pelops, as a meal to the gods, and is punished by being imprisoned in the Underworld where fine foods are forever just out of his reach, as punishment. There is another story with a similar theme in the Atreides family. Atreus, the father of Agamemnon and Menelaus, finds himself challenged by his brother, Thyestes, for the throne. (AN ASIDE: Before I tell this story, it is worth noting that there is another tradition in which Clytemnestra first marries Tantalus – this time a son of Thyestes – who is murdered by Agamemnon so that he can marry Clytemnestra. Nothing says ‘love’ so much as the murder of your spouse, and this certainly would give Clytemnestra another motive for killing Agamemnon, but in Aeschylus’ play, the reference to Tantalus is for the charmer who feeds his child to the gods.) Atreus banishes Thyestes for his attempted coup, but later allows him to return from exile. He holds a feast for him, but at the end of the feast Atreus presents his brother with the hands and feet of his sons, who have been cooked and served to their father. The significance of this for The Oresteia is that the impact of crimes rarely ends with the perpetrators, but exists like an offending stain on an old family lounge, passed down from one generation to another. Of course, Thyestes’ other son, Aegisthus, has a part to play as well. It’s all revenge, revenge, revenge. In The Libation Bearers the Chorus responds to Electra’s increasingly strident calls for revenge:

- It is the law: when the blood of slaughter

- wets the ground it wants more blood.

But in this world the duty to revenge or the culpability for a crime never rests with the principals, alone. In Agamemnon the Chorus explains that revenge breeds violence from one generation to the next. Of Agamemnon, the Chorus says,

- But now if he must pay for the blood

- his father’s shed, and die for the deaths

- he brought to pass, and bring more death

- to avenge his dying, show us one

- who boasts himself born free

- of the raging angel …

In Robert Fagles’ and W.B. Stanford’s introduction to my edition of the plays, they describe it this way:

They are cursed, their lives are an inherited disease, a miasma that threatens the health of their community and forces them, relentlessly, to commit their fathers’ crimes. It is as if the crime were contagious – and perhaps it is – the dead pursued the living for revenge, and revenge could only breed more guilt.

Hence, Atreus’ actions are the catalyst for Iphigenia’s fate, which is in turn for the reason for Agamemnon’s and Cassandra’s murders, and in turn, for the murder of Clytemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus, the surviving son of Thyestes, who wanted some revenge of his own when he conspired with Clytemnestra.

With Helen abducted (or maybe eloping?), the Greek forces are marshalled, ready to sail across the Aegean to extract her from Paris, or lay siege to Troy. But the Greek forces can’t leave Greece because contrary winds prevent them from launching. It turns out that Artemis, who is also a goddess associated with childbirth, is still incensed at the murder of Thyestes’ sons, and this wind is sent by her. This is where everything turns bitter for Agamemnon, although he won’t taste the bitterness for another ten years, after Troy has been defeated. It is determined that the only way to launch the fleet is by offering Artemis a sacrifice. The choice of Iphigenia seems unthinkable, but it answers to that need for intergenerational retribution, and it is the reason why everything that happens in The Oresteia, happens.

Modern Elements in the Play

The social and historical contexts which produced The Oresteia are long gone. It is the purview of scholars to speculate and argue about the staging of the plays and how they might have been received. But as modern readers we form an unintended and unimagined audience for these works. We may read them out of curiosity, and they can certainly be read purely for the pleasure of reading, but I think they might serve more than one purpose. I think the ending of The Eumenides tells us something about what Athenians valued about their city, for instance, which is a matter of historical interest. As Athena persuades the Furies to moderate their implacable desire to exact revenge (to become the Eumenides – the ‘kindly ones’, instead), they begin to speak more positively as their hatred dissipates, of the economic interests Athenians have and how they might make a positive contribution for Athens. They promise to limit winds that affect olive trees, as well as the extreme heat and extreme cold that affects the growth of olives; to stop blight which affects the production of fruit; they highlight the importance of sheep to Athens, which the Furies promise will increase in numbers; and they implore Hermes to reveal more seams of silver. Athens had used the wealth from the silver mines at Laurion to fund the production of its fleet that turned back the Persians. So, we get a sense of where Athens’ economic interests lie.

However, the plays may also speak to us as modern readers on our own terms. To borrow a word from Professor Tolkien, the plays have ‘applicability’. If it was Aeschylus’ purpose to moralise, to celebrate the strength and superiority of Athenian courts, its democracy or its economic position in the world to his audience, these have little relevance for us as modern readers, except in the matter of our curiosity (which is not to be disparaged!) But if we wish to find relevance in the plays in the context of our own world and set of values, we may find they are rich in relevance due to their ‘applicability’. By this, Tolkien meant how any work may be received by a reader as relevant in themes to their own situation, rather than as an allegory – a term Tolkien despised – which limits the power to transmit and control meaning to the author, alone. I believe Fagles and Stanford understand that the plays have a modern relevance, though they never make this argument so directly in their introduction. Instead, they repeatedly characterise the plays as a broad movement from the first play to the last (as T.H. White characterises it in The Once and Future King) as a world where “might is right” to a world predicated upon the idea of “might for right”: that is, a society committed to the use of its economic, military and political power to create a society which serves the rights and needs of citizens. Fagles and Stanford allude to this kind of movement four times in their introduction as a “passage from savagery to civilization”. They also use phrases like “the evolution of a culture” and a “triumph of the Mean”, by which they mean a balance between conflicting interests and needs – an in-between or compromise which negates the rule of force, thereby serving democracy and its institutions, like courts. In the end, this is where The Oresteia is heading.

For us, it is a belief enshrined in some aspects of Enlightenment thinking: a belief in the rights of the individual, like free speech, representation and right to a trial: rights enshrined within the American Bill of Rights, for example, itself an Enlightenment text. And these extend, but are not limited to, Thomas Paine’s notion of natural rights, or Rousseau’s idea of a social contract, as further examples, which define the place of an individual in society, in which they have limited freedom in exchange for the benefits and protections conferred by society. Our modern world is based upon the notion of individual rights which cannot be summarily removed by the state, and by which the state also protects us through the limitation of natural rights in order to form a society. If you are interested in this idea, you can read my review of Rousseau’s Social Contract by clicking here.

These are values which should be important to us and which many argue are being challenged by conservative governments in some countries at the moment: challenges which may limit individual rights and impose more authoritarian forms of government upon citizens. It has been happening in Hungary under Viktor Orbán, and the opening weeks of Donald Trump’s second term as president have seen moves to limit government oversight, while the power of courts and the justice system have been challenged by Trump’s appointments and the pardoning of violent offenders from January 6. In broad historical terms, it is the shift between liberal and conservative ideals which generally fluctuate over time. In The Oresteia, Aeschylus dramatizes the traumatic consequences of hateful retribution based on individual power, and moves his audience towards a vision of a society based upon the rule of law and the rights of citizens: a movement which is in tandem with the confidence and pride Athenians take in their society.

The Status of Women

Yet, however modern we might wish to believe Aeschylus is, we have to remember that he lived in a society largely alien to us two and a half thousand years ago. We might find ‘applicability’ in his notions of justice, but we cannot expect that the values of Aeschylus’ world will mesh with our own. I think this is most apparent in the matter of women.

First, women play a prominent role in these plays. Clytemnestra has been nominally in charge of Argos since her husband left for the war. Elektra allies with her returned brother, Orestes, and is instrumental in her mother’s death in the second play, even if she does not do the killing. And in the third play, Athena sits in judgment of Orestes, while the Furies, women with supernatural power to exact punishment, and who plague Orestes across Greece for the crime of matricide, demand vengeance.

A feminist reading of the plays might reveal a different journey in the trilogy that is a less positive interpretation of this “passage from savagery to civilization”, as characterized by Fagles and Stanford. At the beginning of Agamemnon, Clytemnestra is in power, but her power exists only in the absence of her husband. The Leader of the Chorus, who represents the old men of Argos in this play, states:

- We respect your power.

- Right it is to honour the warlord’s woman

- Once he leaves the throne.

But Clytemnestra now faces the return of Agamemnon, whom she secretly despises for killing their daughter. As modern readers, this is where our idea of “applicability” doesn’t serve us well. It is Clytemnestra whom the play encourages us to abhor, not Agamemnon, who is always portrayed as her victim. Clytemnestra is often portrayed as unnatural, which is always code meaning an unnatural woman: not feminine. We already know, before the Chorus Leader validates Clytemnestra’s authority while speaking to her, that the Chorus secretly fears what she will do as retribution for Iphigenia’s death:

- I beg you, healing Apollo, soothe her before

- her crosswinds hold us down and moor the ships too long,

- pressing us on to another victim …

- growing strong in the house

- with no fear of the husband

- here she waits

- the terror waging back and forth in the future

- the stealth, the law of the hearth, the mother –

- Memory womb of Fury child-avenging Fury

It’s the line “here she waits” that stands out for me. Clytemnestra is patient and unforgiving, her actions long planned. Cassandra, who is gifted by Apollo with foresight and so foresees Clytemnestra’s crime, thinks Clytemnestra monstrous: a “monster of Greece”; a “viper coiling back and forth”. Clytemnestra does not do well in representations of her in these plays. She is also a “sea-witch”; a “lioness” who “beds with the wolf [Aegisthus] when her lion king goes ranging”; and Agamemnon, who is insensible of his fate, lies in “the black-widow’s web”, which is a rather fitting image to complement Clytemnestra’s patient wait for revenge: a spider waiting to strike.

Rather than respecting the rightful power of Clytemnestra in the absence of her husband, we see that the Chorus is full of dread at the untameable power of the mother, directed by the “Memory womb” desiring vengeance for the death of her daughter. And we perceive Clytemnestra has not been a popular leader. The Leader of the Chorus tells the Herald who has brought news of the victory at Troy, “For years now, only my silence kept me free from harm.” The Herald asks, “What, with the kings gone did someone threaten you?” The Leader of the Chorus replies, “So much … ” but cannot explain further. Clytemnestra is an intimidating leader.

Clytemnestra’s rule is portrayed as unnatural, and this is further emphasised by the role Aegisthus plays. As a son of Thyestes, he has a plausible reason for seeking revenge against Agamemnon, if only that he might strike at the son of the man who killed his brothers. But it is in his boasting that we reflect further on the representation of Clytemnestra. “Link by link I clamped the fatal scheme,” Aegisthus tells the Leader of the Chorus, hoping to claim some credit for Agamemnon’s overthrow, and he further boasts, “I’ll bring you all to heal.” Aegisthus plans to rule Argos through Clytemnestra, or usurp her power, but he has not been able to do the killing, himself. He lacks the fortitude of a leader. “You rule Argos?” the Leader of the Chorus asks in disbelief, “You who schemed his death / but cringed to cut him down with your own hand?” Aegisthus looks weak and he is reduced to making impotent threats against the Leader of the Chorus as the play ends – “You tempt your fates, you insubordinate dogs.” Meanwhile, Clytemnestra dismisses the Chorus: “Let them howl – they’re impotent. You and I have power now.” She is full of masculine vigour, and she is frightening.

Clytemnestra assumes masculine power while, traditionally, women wield soft power through influence. But Clytemnestra kills Agamemnon and Cassandra herself, not Aegisthus. In The Libation Bearers, when she hears that she is under physical threat, Clytemnestra calls for her axe. She is a Spartan daughter, after all. But when she recognises Orestes, she is reduced feminine power, once again. Clytemnestra has had a dream which has unsettled her. She dreams she gives birth to a snake which bites her nipple and curdles her milk when she tries to suckle it. The birth is another example of her unnaturalness as a mother and a woman. Orestes understands the import of the dream, as it is reported to him:

- As she bred this sign, this violent prodigy

- so she dies by violence. I turn serpent,

- I kill her.

By rejecting a masculine response to threat, Clytemnestra’s desire to reconcile with Orestes leaves her somewhat exposed to reprisal. She has no justification or desire to kill her son. But when pleading with him fails, Clytemnestra resorts to a curse: “the hounds of a mother’s curse will hunt you down.”

In essence, Clytemnestra’s curse is merely an appeal to the old kind of justice. It is heard by the Furies, who plague Orestes in his journey through Greece, before he arrives at Athens in The Eumenides, where he is put on trial for his mother’s death. In The Eumenides we witness two concepts of justice in conflict: the idea of vengeance, which has resulted in intergenerational violence and can only result in more, or the institution of a formal court in which justice is dispensed by the citizens of Athens.

This innovation seems familiar; modern. But the basis of it would be anathema to modern ideals, since it rejects a political role for women in the polis. Apollo, who is in favour of the court, first offers something of a defence for Orestes. He explains he had ordered Orestes to kill Clytemnestra as revenge for the death of Agamemnon, or else face punishment from the god, himself. Clytemnestra’s unnatural female propensities are again foregrounded by Apollo as a part of that defence: “… she shackled her man in robes, in her gorgeous never-ending web she chopped him down!” But Orestes’ own testimony offers a difficulty for the court. He neither denies the murder nor is he remorseful: “Strike I did, I don’t deny it so.” And the Leader of the Chorus (the Chorus in this third play is the Furies and their Leader, who wish to exact their vengeance against Orestes) attempts to negate Apollo’s withering advocacy. She does this by reminding the court of Zeus’ own actions, which are akin to Clytemnestra’s: “He shackled his own father, Kronus proud with age.”

The argument here draws an equivalence between Zeus’ actions, which helped to bring him to power, and Clytemnestra’s, which were her undoing. In defending Clytemnestra’s revenge against Agamemnon, the Leader of the Chorus attempts to undermine the legitimacy that Apollo is attempting to establish for Orestes’ actions by arguing that Orestes had no right to seek revenge in a case of applied justice. But Apollo turns this against the Leader with a reasoned argument that we may understand in the context of modern debates about capital punishment:

- Zeus can break chains, we’ve cures for that,

- countless ingenious ways to set us free.

- But once the dust drinks down a man’s blood,

- he is gone, once for all.

Apollo reminds the court that what is at stake is not imprisonment, but Orestes’ life. The Leader of the Chorus, however, questions whether a man might kill his mother, be acquitted and then return to the life he might otherwise have lost. Modern responders might speak about the burden of proof, the presumption of innocence or of mitigating circumstances as a counterargument, but Apollo replies with an argument that would seem strange, even offensive, now:

- Here is the truth, I tell you – see how right I am.

- The woman you call the mother of the child

- is not the parent, just a nurse to the seed,

- the new-sown seed that grows and swells inside her.

- The man is the source of life – thew one who mounts.

- She, like a stranger for a stranger, keeps

- the shoot alive unless god hurts the roots.

It is a response that is bound to displease most modern readers, I would think. Women have no real stake in their child, Apollo argues. They are merely the tilled land in which the seed is grown. Ipso facto, Clytemnestra could have had no real stake in the life of Iphigenia. Agamemnon, who is the seed, could dispense with her as he needed. So, Clytemnestra’s killing of Agamemnon could not be justified by any argument as a justified revenge. Which means that, according to old notions of revenge, Orestes’ matricide was justified, since he avenged a wronged father.

At least, that seems to be the logic of it.

Here is where the idea of ‘applicability’ becomes problematic for us as modern readers. This is not a modern defence. It is not modern thinking (one hopes!) As much as we might abhor revenge as a form of justice, it is not logical to say one murder was one thing and the other, another.

But rather than dismiss the speech, and therefore the play and maybe the trilogy out of hand, let’s put aside a desire for ‘applicability’, and once more turn to curiosity. This is not a modern play, so we may wish to understand it on its own terms: to seek understanding of the past, or at least to salvage what we might accept from the play, itself; to understand there are ideas here that can still appeal.

If we are willing to make this mental adjustment, we have to remember that Athens was not a modern democracy (despite Aristophanes’ play, The Assemblywomen, a satire which actually worked because the notion of women in politics would have seemed absurd to Athenians). Athens kept slaves. It cloistered women, particularly women of wealth and high status. Political power was wielded through male citizens by means of the vote. Women could not appear in court as jurors. In essence, women had no legal status separate to a father, husband or family. It was a patriarchal society in the truest sense of the word. The Greek word, ‘pater’ (πατήρ), meaning father, is the root for the English word, ‘patriarchy’. As a patriarchal society, children belonged to the family. In addition to this, law existed as an act of patriarchal agency and intent. In the Greek world, it is Clytemnestra’s power as a female leader that is unnatural, rather than Agamemnon’s sacrifice of Iphigenia. At least, as a logical argument, this might have made some sense. Because if this sort of thing made sense in the hearts of ordinary people – sacrificing one’s own child – this story wouldn’t have its appeal. Let’s be clear about that.

But like Clytemnestra, Athena, who presides over this court, wields patriarchal power. Though she is a woman, this is what she represents. Athena is another unnatural woman in this play, it seems, but she gets away with it because she is a goddess.

- No mother gave me birth.

- I honour the male, in all things but marriage.

- Yes, with all my heart I am my Father’s child.

- I cannot see more store by the woman’s death –

- she killed her husband, guardian of their house.

According to Apollo, Athena’s existence is the literal proof of male generative powers: “The father can father forth without a mother” he tells the Leader of the Chorus (ie of the Furies), and Athena is of “such a stock no goddess could conceive!” And in her judgement, Athena reinforces this position: “Yes, with all my heart I am my Father’s child.” Athena rejects the notion of female civic power. She, herself, is a surrogate for her father’s power. This is the basis upon which the plays represent an evolution from Fagles’ and Stanford’s “savagery to civilization”. For modern readers, it may be less than satisfying, but it still represents an evolving society that is a precursor of our own.

The Mean

As for the verdict itself, it is such a close call that it allows for dissenting voices in the audience. Should Orestes be acquitted of a murder he admits to; for which he has no remorse? Perhaps the real justice lies in the process, not the outcome, which is suggested by the doctrine Athena lays down for the court in the closing sections of the play:

- Worship the Mean, I urge you,

- shore it up with reverence and never

- banish terror from the gates, not outright.

- Where is the righteous man who knows no fear?

By worshipping the “Mean” the Furies are encouraged to respect the process of the law, even if the law must reserve a measure of fear to be effective. In the end, this isn’t so far from what the Furies have themselves already argued. Athena understands she must balance the old justice of retribution with a new justice predicated upon evidence. But as zealous as their rage appears, even the Furies understand the need for this ‘Mean’. They have already articulated it, themselves:

- Is there a man who knows no fear

- in the brightness of his heart,

- or a man’s city, both are one,

- that still reveres the rights?

- Neither the life of anarchy

- nor the life enslaved by tyrants, no

- worship neither.

- Strike the balance all in all and god will give you power;

- the laws of god may veer from north to south –

- we Furies plead for Measure.

In attempting to straddle this happy ‘Mean’ (or “Measure”), Athena meets the complication, that a judgment from her may be as problematic as the unilateral justice of the Furies: “So it stands. A crisis either way.” The solution is the invention of a jury of ten men to make the decision, which becomes the standard by which the process is trusted.

Conclusion

It's a convoluted reasoning, I know, but what emerges from The Oresteia is a set of attitudes about women we might dismiss, but they are attitudes which, at the same time, help to form the basis for some of what we might appreciate in the plays, too. As The Eumenides winds down, Orestes has been acquitted and Athena is left to defend her court against the Furies who are angry. They are at first unwilling to accept the judgment. They feel humiliated and they call for destruction, or else their ancient rights will be negated. This is all bluster that will blow away. An emotional response by women, if we might return to that argument momentarily, that will be subsumed by Athena’s new, masculine court. Against their anger, Athena urges moderation and argues they bear no disgrace. She offers them a vision of a future in which they take on a new role and share in the prosperity of Athens. Rather than raw power, the goddess employs “the majesty of Persuasion” to placate the Furies and ease them towards their new role as the Eumenides. Athena’s persuasion is core to the values of the democracy. Argument, reason, persuasion and incentive are the means by which civil society moves forward, rather than violence, revenge and retribution. It is easy to imagine the chord this would have struck with the Athenian population, just as much as these broader ideals – setting aside for the moment more troublesome attitudes to women – can still strike a chord with readers, today.

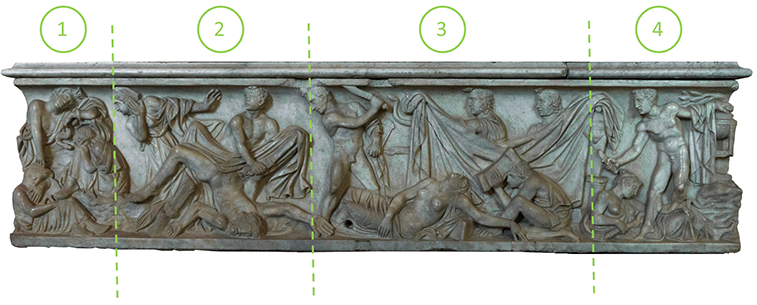

This is the complete frieze on a first century Roman Sarcophagus that depicts four key scenes from the story of The Oresteia. I have divided the image into four sections for ease.

- Agamemnon lies dead and is mourned by Orestes and the Furies.

- Orestes kills Aegisthus while holding up a cloth to hide the terrible scene. To his left a nurse holds her hands to her face, horrified by what she sees.

- Orestes kills Clytemnestra. She lies at his feet, dead. A servant holds a stool above his head to protect himself, and the Furies, who can be identified by their snake-like hair, hold a sheet to cover the murder.

- Orestes is at the Temple of Apollo where he seeks to be cleansed of his crime while a Fury sleeps at his feet.

Summaries

I have written brief summaries of each of the plays in The Oresteia. Because of their brevity the summaries necessarily leave out details and lack nuances which can only be appreciated by reading the plays, themselves.

Agamemnon

It is ten years since the Greek force left for Troy and a watchman stands sentry during the night in Argos, watching for a signal fire that will announce victory. He sees a signal fire and leaves to break the news. Some old men who haven’t seen the signal (the Chorus) enter. Their role at this point is to give exposition about the expedition to Troy. Clytemnestra enters and lights the alter fires but ignores the old men as they continue to speak about Troy. They recall the beginning of the expedition and the sign of two eagles devouring a hare – a good omen – but nothing has happened since. They recall how the Greek fleet was initially unable to launch because of strong winds sent by Artemis, and how Calchis, the seer, declared a sacrifice would need to be made. Agamemnon sacrificed Iphigenia, his daughter.

Clytemnestra announces that Troy has been defeated. She describes the signal fires that have been lit all the way from Troy to make the announcement. In front of the old men Clytemnestra speaks proudly of the defeat of Troy and of the treasures taken from the city. She expresses her hope that the victors do not now tempt fate by displeasing the gods. The Chorus praises Zeus and prays for restraint from their leaders at Troy. The Chorus recalls how Paris and Helen brought shame to their people, as well as the tragic loss of life from the war which has been fought on their behalf. The Chorus is pleased at news of the end of the war, but asks if there is any other evidence besides the signal fires to show that this is true. At this point a Herald enters, sings Agamemnon’s praises and announces that Troy is defeated. The herald speaks of the poor conditions for the soldiers at Troy, but does not speak of the cost in human life, only the spoils of victory.

Clytemnestra appears eager for Agamemnon’s return. She acknowledges that she has committed adultery with Aegisthus, but she says that her bond with Agamemnon remains strong. Menelaus, Agamemnon’s brother, is said to have been separated from the fleet by a storm, and is lost for the moment. In other words, he will be absent for the events of this play.

The Chorus is critical of Helen. In the modern translation by Robert Fagles there are associations made between Helen’s name and hell. She is described as a lion that is raised from a cub that turns on those who treated it well.

Agamemnon enters, and in his presence the Chorus now speaks of the war as a great victory, and ceases to speak of its costs. Agamemnon expresses the opinion that Troy brought about its own ruin. Now that he is back, Agamemnon intends to assess the state of his city. Clytemnestra expresses to the chorus the uncertainty she has lived with in Agamemnon’s absence, and speaks of suicide attempts she made because of the burden. She speaks to Agamemnon of their son, Orestes, who is no longer living in Argos, and of the risk Agamemnon took leaving his city unattended to go to war for so long.

On the pretext of celebration, Clytemnestra encourages Agamemnon to walk on rich tapestries, but Agamemnon is wary, believing it an act of hubris which could offend the gods. Priam, Agamemnon admits, would have done it. He is eventually persuaded to walk on the tapestries. Clytemnestra says he should glory in their wealth, but then she also compares Agamemnon to Zeus, trampling grapes for wine. All this gives the Chorus a deep sense of foreboding. The Chorus understands that even a king can suffer a sudden reversal of fortune.

Clytemnestra encourages Cassandra, Agamemnon’s lover from Troy and the daughter of Priam, to leave the chariot in which she has stood all this time. Cassandra remains standing in the chariot and Clytemnestra becomes impatient and angry with her. She declares that Cassandra is mad and leaves her to re-enter the palace. What takes place next makes Cassandra look mad. She seems to talk in riddles. She says Apollo is her destroyer and other things the Leader of the Chorus struggles to understand. But then she predicts the murder of Agamemnon by Clytemnestra. Cassandra tells how Apollo gave her the power to see the future, but because she refused to bear his child, he cursed her so that she would never be believed. Nevertheless, the circumstances of Agamemnon’s return and what Cassandra says actually makes the Chorus believe her. She portrays Clytemnestra as a monster and reiterates that Agamemnon will be killed. She also predicts her own death. But she says that Orestes will return to avenge their deaths.

Cassandra leaves and the Chorus is upset, wondering how the endless cycle of vengeance can be stopped. Suddenly, there is a cry off stage. It is Agamemnon. The Leader of the Chorus suspects he is being murdered. The Chorus opens the door to reveal the corpses of Cassandra and Agamemnon. Clytemnestra takes responsibility for the killings. She reveals her long grief for the death of her daughter, Iphigenia. She openly speaks of Aegisthus as her lover and says that Agamemnon brutalized her. She feels Agamemnon’s murder is justified because he sacrificed Iphigenia to the gods. She says that Iphigenia will greet Agamemnon in heaven. Clytemnestra, at this moment, says she will willingly accept justice for what she has done.

Aegisthus enters triumphantly. He recalls how Agamemnon’s father, Atreus, fed his brothers to his own father, Thyestes, which has fueled his own desire for revenge. He boastfully claims to have killed Agamemnon, but under questioning from the Chorus, he says he helped plan the murder but did not commit it. Aegisthus plans to rule Argos, but the Chorus is skeptical, suggesting that if Aegisthus could not kill the king, himself, he is not strong enough to lead. Aegisthus and the Chorus almost come to blows. Aegisthus and Clytemnestra are unrepentant. They believe that their act has been an act of destiny, and that their new power will allow them to right the wrongs of the past.

The Libation Bearers

Several years have passed since Agamemnon’s death. Orestes, the son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, finally returns home from exile with his companion, Pylades. Orestes is already thinking of revenge against his mother. We learn later that he has been ordered by Apollo to seek his revenge. Orestes and Pylades see a group of women headed by Orestes’ sister, Electra. They seem to be a part of a religious procession, possibly to bear libations for Agamemnon at his grave. Orestes and Pylades decide to withdraw to see what they are doing. They learn that Clytemnestra has been haunted by a dream and has sent her libation bearers to offer libation, hoping to ward off retaliation from the dead or the gods for her crimes. As time goes on, Clytemnestra is aware that retribution for her act is drawing closer. In this play the Chorus is a group of slave women from other cities who accompany Electra. As they offer libations on her mother’s behalf, Electra finds it difficult to find appropriate wording for the offering, since it would normally be made on behalf of a loving wife. Electra encourages the Chorus to be open and honest with her. She says she holds a hatred in common with the Chorus, Aegisthus, her mother’s lover. The Leader of the Chorus suggests Electra pray for her brother’s return and for revenge. Electra is reluctant to be corrupted by revenge. But as she makes her libations, she remembers how her mother and Aegisthus enjoy the riches of her father’s house together, and she increasingly works herself up to the idea of revenge, and she prays for an avenger. When she is finished, she notices a lock of hair on her father’s grave, which she identifies as very much like her own, and then sees Orestes’ footprints, which she believes are Orestes’.

Finally, Orestes reveals himself to her. She almost cannot believe he is back. He shows her the clothing he wears, made by her hand, as proof. Electra expresses her love for her brother and her hatred of her mother. Orestes offers a prayer to Zeus for their protection. He explains that he has been tasked by Apollo to avenge his father’s death, or else suffer punishment himself. The Chorus calls for vengeance. Orestes speaks to his father’s grave, and as he speaks Electra’s desire for revenge becomes even stronger. They call on the spirit of their father to give them strength for their undertaking, and they sing a dirge to stir Agamemnon to support them supernaturally.

As the dirge ends the Leader of the Chorus reports the details of Clytemnestra’s nightmare. She has dreamed that she gave birth to a snake which bit her nipple when she tried to suckle it, and it has curdled her milk. Orestes interprets the dream as a portent of his mother’s death at his own hands. They make a plan. Electra will return to the city as though nothing has happened. Orestes and Pylades will arrive at the city disguised as foreigners seeking hospitality. Once they have been given admission, Orestes will first kill Aegisthus.

They arrive at Argos and the plan goes smoothly. They are given admission. Orestes pretends he has a message. He says that Orestes is dead. Clytemnestra is moved by this news. Despite the bad news, Clytemnestra offers the ‘strangers’ her hospitality. Meanwhile, Orestes’ old nurse, Cilissa, has heard the news of Orestes’ death and is upset. She recalls him as a child. She decides to fetch Aegisthus to tell him the news. She despises him. The Leader of the Chorus tells Cilissa to ask Aegisthus to come without his body guard, and then prays to Zeus for Orestes’ success. Aegisthus enters. He is concerned about the impact the news of Orestes’ death will have on the house. Aegisthus leaves the stage. The Chorus is also aware of the danger the news presents, but also sees that it might be a new beginning.

There is a scream off stage and then a wounded servant of Aegisthus enters and announces that he has been killed. The Chorus now anticipates Clytemnestra’s death.

Clytemnestra hears the commotion and is told by a servant that there has been a murder. She asks for her axe, resolved to fight. The main doors open revealing Orestes standing over the body of Aegisthus. Clytemnestra now recognizes her son. She begs for her life and says they can grow old together. Orestes accuses her of casting him aside as a child. She tries to spin the situation by saying he was merely placed in a comrade’s house. But she perceives that Orestes is determined to kill her. She warns him that if he does, he will be cursed by the hounds of a mother’s hate. In a moment of insight, Clytemnestra realizes that Orestes is the snake of her dream. Orestes forces her over the threshold of the main door.

The Chorus wonders whether this act will be the “summit of bloodshed”, suggesting a hopeful anticipation that this killing will end the intergenerational cycle of revenge. The murder, after all, is sanctioned by Apollo, and it is a long-waited justice. When the doors open again Orestes and Pylades are standing over the bodies of Clytemnestra and Aegisthus, a sight which recalls the murder of Agamemnon and Cassandra in the first play. Now Orestes unwinds the bodies from the robes that were once used to trap Agamemnon in his bath and declares that he has pursued a just retribution. He says he once loved his mother, but now loathes her.

As the Chorus congratulates Orestes on his accomplishment he suddenly screams in terror. He sees shrouded women stalking him, and he realizes the curse his mother called upon him is now taking effect. He will be haunted and pursued by the Furies. He cannot stay in Argos. He feels driven on by these forces, unseen by others.

The Eumenides

The Furies have pursued Orestes to the temple of Apollo. The Priestess, Pythia, collapses in shock when she discovers him at the Navelstone, his sword drawn and blood on his hands, with the Furies sleeping beside him. Apollo appears and pledges to protect Orestes. He is disgusted by the Furies who have pursued Orestes, and he promises to bring him to a trial that will exonerate and free him. Apollo summons Hermes to protect Orestes and lead him back into the world. Orestes leaves with Hermes as the Furies continue to sleep.

The Ghost of Clytemnestra appears. She describes how she is an outcast in the Underworld for the murders she committed, despite the libations she made. She is bitter that there appears to be no consequences for Orestes. She urges the Furies to awake and pursue Orestes. They awake, but Orestes has slipped away from them. Apollo drives the Furies from his temple, saying they are monstrous and lawless. The Leader of the Chorus/Furies confirms with Apollo that he commanded Orestes to kill his mother. She argues that matricide is worse than killing one’s spouse, since it is murdering one’s own blood. Apollo says their pursuit of Orestes is unjust, and he will have Athena preside over a trial for Orestes. The Leader of the Furies is adamant that they will continue to pursue Orestes.

In a change of scene, Orestes enters the temple of Athena on the Athenian Acropolis and hugs the idol, intending to remain there to await his trial. The Furies enter the temple and do not see Orestes clutching the statue’s knees at first. When they see him at the idol, they tell Orestes they do not want him to receive a trial. Rather, they want to drain his blood. Orestes has been purified in Apollo’s temple and he feels a distance between his present self and the crime for which he is pursued. He calls on Athena’s support and promises her his fealty and the fealty of his people if she helps him. The Furies do a dance and sing a song, like they are performing a spell, to try to bind Orestes while he awaits Athena’s reply. The Furies assert their independence from the gods.

Athena enters the temple, armed with her shield and spear. She says she has just returned from Troy where the land has been dedicated to her. She demands to know who is in her temple. The Furies reveal themselves as “Curses.” They tell her that Orestes murdered his mother, but Athena perceives there is more to the story, understanding that Orestes was urged into action. She believes the Furies’ concept of justice is maligned. The Furies show respect for Athena and agree to turn Orestes over to her if she is to be the judge. Athena urges Orestes to speak. He explains that he has already performed rituals to purge himself of his crime. He explains how Apollo urged him to do it. Athena says if he is innocent she will adopt him for Athens. But she understands that the Furies will be enraged if Orestes is acquitted, and she realises that either way, she faces a crisis. She decides to appoint ten Athenian men to pass the judgment after the trial is conducted.

The Furies admit that they believe an acquittal for Orestes will set a dangerous precedent, and they are concerned that their involvement in the trial is already weakening their power by allowing men, rather than them, to pass judgment. In the future, people will call in vain for vengeance. The Furies ask that a balance is reached in the judgment between anarchy and a court that will become tyrannical. Just men should never be judged harshly, while those who are reckless should face the consequences of their actions.

The action moves to the Areopagus where the trial begins. Apollo takes responsibility for urging Orestes to kill his mother. Orestes admits that he killed her and describes the deed. He has no remorse. She not only killed her husband, but also his father he explains. The Leader of the Furies dismisses Clytemnestra’s own crimes since Agamemnon was not related to her by blood. Orestes says he acted at the urging of Apollo who was following the will of Zeus. Apollo recounts the killing of Agamemnon in detail, with great sympathy for him, while he portrays Clytemnestra as monstrous.

The Leader of the Furies is dismissive of Zeus’ name, presented during the trial as an authority for Apollo’s instructions and Orestes’ action, since he, himself, shackled his father Cronus. Apollo points out that shackles can be removed, but once a man is put to death, not even the gods can bring him back to life. The Leader of the Furies asks if a son can be acquitted after shedding his mother’s blood. Apollo responds with an argument that women are not the true parents of their children, which is meant to free Orestes from the obligation of blood they say he owed his mother.

The judges are told to make their decision. As they deliberate, Athena declares that this new court will remain a permanent feature of Athenian justice. She believes it is an ideal expression of the law, removed from the desires of men and their quest for power. The judges cast their lots, but before the decision is known the Leader of the Furies becomes angry, threatening that she and her Furies will meddle in Apollo’s oracles and crush the land of the Athenians if Orestes is acquitted. Athena declares that if the vote is even, she will break the tie and vote to acquit Orestes. When the votes are counted they are, indeed, evenly split. Athena declares that Orestes will go free. Orestes swears an oath of fealty to Athena, as he promised he would, and that he will enforce the oath for his people. Orestes leaves.

The Furies are incensed. They accuse the gods of degrading the ancient laws. Athena responds, saying that their power has not been overturned by this decision. But the Furies feel they have been humiliated by the judgment and call for widespread destruction. Athena calls for moderation and peace, but the Furies continue to see the verdict as a personal affront. Athena offers the Furies a vision of the future in which they have a productive role to play in the life of the city where civil strife is no more. She speaks of her determination to speak well of the Furies, and insists she wishes to persuade them rather than rule over them. But she cannot accept the vengeful destruction of Athens when she is offering them a role in Athenian prosperity. The Furies are somewhat placated and begin to allow themselves to be persuaded. Athena continues to mollify them with talk of the place they will hold in the city and the future greatness of Athens. Finally, the Furies embrace Athena’s offer and promise that they will help to ensure Athens’ economic success through favourable winds, fertile animals and mineral rich soil. Athena declares that she loves Persuasion, which is an instrument of democracy, while the Furies renounce vengeance in exchange for the opportunity to share mutually in Athens’ joyful future. At this point the Furies have been transformed into the ‘kindly’ women suggested by the word ‘Eumenides’ in Greek.

Scenes from The Oresteia

No one has commented yet. Be the first!