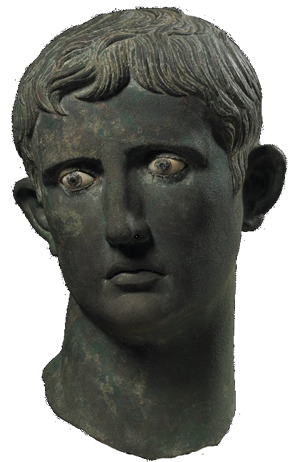

By the end of his life in CE 14, Augustus had ruled Rome for over forty years as its first emperor. He had met no military challenge from a Roman army since he defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra in the sea battle at Actium in 31 BCE. Augustus’s achievements were wide reaching, having reformed the government, economy, laws and brought stability to the empire after the murder of his adoptive father, Julius Caesar, in 44 BCE. Given the turmoil of the Civil War decades, as well as the excesses of emperors like Tiberius and Caligula who followed him, it is easy to accept Augustus’s reign as an enlightened historical interlude: the Pax Romana. He took charge of the greatest empire the world had ever known as a young man and imposed his will upon it. In his later life, Augustus’s attempts to secure a smooth transition of power after his death indicates the responsibility he still felt for the future prosperity of Rome. Yet John Williams’s novel, Augustus, suggests that while Augustus may have been deified, we must assume he was wracked by the same doubts and personal pain as anyone else, and this forms the subject of his fictional account of Augustus’s life.

Shakespeare’s representation of Octavius – Augustus’s name in earlier life – does not sit so well with this image of the divine and benevolent ruler of the empire. Particularly in Antony and Cleopatra, Octavius’s ambition and military power stands in contrast with what has been accepted in popular culture as a transcendent love between the eponymous characters. Antony and Cleopatra are a middle-aged Romeo and Juliet, killing themselves at the moment of their political downfall, seeming victims of Octavius’s rapacious ambition. At least, that’s how Octavius is read by some critics of Shakespeare, and Shakespeare drew upon the characterisation of Tudor historians who were able to mark a distinct delineation between the younger, ambitious Octavius and the older benevolent Augustus.

Williams dramatizes Octavius’s rise to power after the murder of Caesar, his period as emperor and eventual death through a series of imagined letters, journals and other records, with a minimal use of actual historical texts. The use of the epistolary mode allows Williams to characterise the complexities of the period and its people by avoiding a single narrative perspective, as well as giving insight into the inner life of his main characters, Octavius/Augustus and his daughter Julia, his only biological child. Furthermore, the novel is divided into three books. The first is dominated by the political and military manoeuvring that eventually sees the downfall of Marcus Antonius – Mark Antony – and Octavius’s rise to power along with his friends, particularly Marcus Agrippa, to whom he would later marry his daughter, Julia. Of the three parts, I found this first the least engaging, despite it being well written and as accomplished as the latter two. This is not really said as a criticism of the book but to put Williams’s real achievement into context. This first book marks a period of action, and while it gives real psychological insight into Octavius’s character, his plans and even his fears, it mostly feels like a prelude to the second part and is not as stylistically differentiated from historical sources as the second part feels.

The second part of the novel focusses more on Octavius relationship with his daughter and her marriages to Marcellus, Agrippa and later to Tiberius. As daughter of the emperor, Julia has little control of her life. She is told who to marry and is expected to produce heirs. Julia’s life is a political expedience, and since her father has only her, she is burdened with marriage to a man who is too old for her (Agrippa) and another whom she despises (Tiberius). The extent to which Julia has power is circumscribed through her relationships with men: the innocent girl and her father; the virtuous wife and her husband). Even for powerful women like Livia, Augustus’s wife and mother to Tiberius, this was the life of women in Rome. Tiberius, for the sake of political expedience, is likewise forced to divorce his wife, Vipsania, whom he loves, to marry Julia, whom he does not. This is where Williams’s novel succeeds, not as a kind of literary gossip magazine or as a piece of military adventurism, but as a study in the sacrifice of one’s personal life and humanity to power.

But the success of this study lies partly in its epistolary style, allowing for multiple voices and perspectives, and thereby making the grief of the protagonists real. Julia was famously exiled by her father to the island of Pandateria for five years and was never allowed to return to Rome. Augustus exiled others in his family as well. His granddaughter, Julia – Julia the Younger, daughter to his own Julia – was also exiled to an island for an affair, as well as Agrippa Postumus, Julia’s son. Yet, while these may receive some mention in Augustus, it is Augustus and Julia – Julia the Elder – who are the focus of this story; their grief and sense of emptiness at the course of their lives. Seutonius, the chronicler of Julius Caesar and Rome’s first eleven emperors, suggests Augustus acted out of anger and honour in exiling Julia:

He wrote a letter about her case to the Senate, staying at home while a quaestor read it to them. He even considered her execution; at any rate, hearing that one Phoebe, a freedwoman in Julia’s confidence, had hanged herself, he cried: ‘I should have preferred to be Phoebe’s father!’’… nothing would persuade him to forgive his daughter; and when the Roman people interceded several times on her behalf, earnestly pleading for her recall, he stormed at a popular assembly: ‘If you ever bring up this matter again, may the gods curse you with daughters and wives like mine!’

Seutonius, 'Life of Augustus'. (The extract from Seutonius is from the Penguin edition, The Twelve Caesars, translated by Robert Graves (1957) and introduced by Michael Grant, Section 65

Seutonius’s portrayal of Augustus’s anger is set within the political sphere: the letter is read in the senate; his angry response is given in the popular assembly. His feelings are expressed as a politician reacting to public opprobrium, separating himself from scandal, as did his adoptive father, Julius Caesar, who divorced his wife, Pompeia, even though no scandal was proved against her, because Caesar’s wife must be above suspicion.

Williams imaginatively reads into the scandal of Julia and the psychological burden her exile placed upon her and her father. Julia was exiled under the adultery laws that Augustus, himself, introduced to address a perceived moral decline in Rome. Williams’s characterisation is compelling because it goes beyond the moralistic politician presented to us by Seutonius, and considers more complex and heart-breaking motivations for Julia’s exile beyond Caesar’s self-serving defence of power. The point is made in the third section of the novel as Augustus takes a voyage to Capri just before his death. Augustus mood is philosophical as he considers his life and his legacy. He has just produced Rae Gestae, the account of his empire as he leaves it for his successor. Now he contemplates the bronze tablets which will adorn the entrance of his mausoleum, bearing the story of his reign and achievements. He calculates that the account of his life’s work will necessarily be limited to just eighteen thousand characters. Augustus reflects that:

. . . just as my words must be accompanied to such a public necessity, so has my life been. And just as the acts of my life have done, so these words must conceal at least as much truth as they display; the truth will lie somewhere beneath these graven words, in the dense stone in which they encircle. And this too is appropriate; for much of my life has been lived in such secrecy. It has never been politic for me to let another know my heart.

It is this tension between the public and private self – between power and love – that Williams captures so well. This is why I felt the beginning of the novel was necessary – it is, after all the first act of the young Octavius who strides upon the world’s stage. Augustus in his philosophical older musings thinks of life much like that of roles played on a stage, echoing Shakespeare’s Jacques. It is this counterpoint between the more private life of Julia and Augustus in the latter part of the novel, played against the political stage of the first part, which is of interest. Augustus’s bronze engraved tablets are an excellent metaphor for that. Augustus is an accomplished novel which offers excellent insights about the human heart and the costs of power.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!