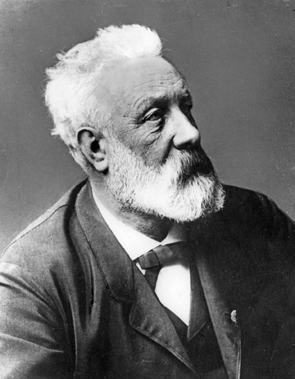

There are some books like Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days that have become a household name, even if few these days have read it. And because of that it is enough for many to acknowledge the story and leave it at that, safe in the presumption that the book is known. Often, knowledge of the story comes from film. There was the 1956 film with David Niven as Phileas Fogg which won the Academy Award for Best Picture, among other things. In that film Fogg’s journey begins in a hot air balloon. I haven’t been able to track down a copy of that yet, but its trailer suggests the film attempts to remain faithful to key scenes in the book, at least. But the association of the hot air balloon as a mode of transport seems to have been set with that film and continued in children’s animated adaptations as well as the 2004 remake starring Jackie Chan and Steve Coogan. In that version Fogg is not the calculating gentleman of the novel, but a bumbling inventor who follows a dream. Naturally, he invents his own flying machine during the course of the movie, having begun his journey in a daring escape in a hot air balloon from Chinese martial arts experts deftly disposed of by Jackie Chan’s character who – believe it or not – pretends to be a Frenchman.

Interestingly, there are no flying machines of any type in Verne’s novel, despite his reputation as a Science Fiction writer and the strong association of hot air ballooning with the story. The closest Verne comes is this sentence near the end of the novel: But the means of crossing the Atlantic in a vessel must be found, unless they went across in a balloon, which would have been very venturesome, and which, besides, was not practicable.

In fact, Fogg’s journey is mostly made by steam train or steam ship – this is 1872 we’re told at the beginning, the modern era of steam – along with a few more eccentric modes of transport, like an elephant in India or a wind-powered sledge in America.

It hardly matters how the story is adapted, whether there be balloons or not. The point is that the book may be familiar by reputation, but its tone and intention may not. Verne’s Phileas Fogg is neither an inventor or bumbling, for instance. He is a somewhat cold and calculated gentleman, a member of the Reform Club, one of the numerous Gentleman’s establishments of the period. (In Michael Palin’s Around the World in 80 Days he began and ended his journey at the Reform Club). Fogg accepts a bet from other members of the Club, who claim he cannot travel around the world in eighty days using modern means of transportation. Fogg asserts that he can, despite whatever mishaps or delays might beset his journey, and he risks £20,000 of his own money to cover the bet. The remaining £20,000 of his own fortune he takes with him to aid him in his journey.

The seeming coldness of Fogg’s character cannot be underestimated, except that he is capable of great humanity as well. Passepartout’s heart is early moved by Fogg’s generosity: he gives twenty guineas to a beggar woman. In the course of their journey, Fogg risks his schedule to save the life of Mrs Aouda, doomed to be ritually killed with her dead husband in India, and again risks his journey in America to mount an expedition to save his servant, Passepartout, after a Sioux Indian attack. But for all that the word used by Verne over and over again to describe Fogg is impassible

. Verne also describes Fogg several times as an automaton

. Fogg seems to possess an inhuman implacability, never, it seems, to be stirred to emotion by the series of delays that threaten his expedition. Like a modern accountant, Fogg keeps a ledger of his losses and gains in his schedule as a reassurance of the precision of his judgment in modernity and rationalism.

All this is enlivened somewhat by the presence of Detective Fix who follows Fogg and Passepartout around the world, hoping to receive a substantial reward for the recovery of £55,000 stolen from the Bank of England. Fix has come to believe that Fogg may have robbed the bank and now hopes to use the bet as a cover to escape England. In the 2004 movie, Fix is a hapless fool who is constantly despatched by either Chan’s Passepartout or other bad guys in a series of prat falls and slap stick endings. In the novel, Verne portrays him as a mistrustful man who ingratiates himself with Fogg and Passepartout and accompanies them on much of their journey. He hasn’t the same endearing quality of the character in the 2004 film, and despite several incidents which should make him question the veracity of his suspicions, Fix never develops empathy for Fogg and never questions his own resolve. This is somewhat contrasted with the character of Mrs Aouda who clearly grows more and more enamoured with Fogg, despite his seeming indifference to her throughout the novel. Fogg is indeed an automaton while ever his gentleman’s honour and money are at stake. He is a product of the exact sciences.

Sir Francis Cromarty, who accompanies Fogg in India, questions whether Fogg had a soul alive to the beauties of nature and moral aspirations.

One may well wonder, since Fogg never willingly slows to enjoy the wonders he passes, choosing instead to leap from one mode of transport to another to fulfil his quest. Cromarty judges Fogg’s journey as an eccentricity without a useful aim.

But to understand Fogg we must also put him in the context of his time and place. Fogg’s iron reserve reflects a national British character in the latter part of the 19th Century that the powerful affected. While most of the public bet against Fogg’s success, Lord Albemarle bets £5000 on him, reasoning If the thing is feasible, it is well that an Englishman should be the first to do it.

Verne, despite being French, seems to admire British culture. It is interesting that he makes a French man subservient to Fogg and reliant upon his rescue in several scenes. The ascendance of British civilisation is also reflected in the route taken. In the 2004 film Fogg and Passepartout, along with their newly acquired companion, Monique La Roche (who replaces Mrs Aouda from the book) travel on the Orient Express to Turkey where there is an amusing scene with Arnold Schwarzenegger as Prince Hapi. But Verne’s route largely encompasses the British Empire of the latter 19th century. Fogg and Passepartout first stop in Paris, but this is only mentioned in an itinerary note early in the novel. Until Fogg reaches America, itself a former British colony, Fogg’s route takes in the Suez Canal in Egypt, a crossing of British India from Bombay to Calcutta, Hong Kong and Singapore. The most substantial scene outside British or former British colonies is in Yokohama, Japan. But even Yokohama was open to international trade at this time, predominantly British trade, and the British had a garrison there to protect its interests. The British started the first daily newspaper in Yokohama, also in English, suggesting its cultural dominance in the city. So, the route Verne chooses for his characters seems designed to highlight and celebrate the cultural dominance of the British Empire. As Verne’s narrator says, There is thus a track of English towns all around the world.

The superiority of the British race is even suggested through the character of Mrs Aouda who, while Indian, has benefitted from an absolutely English education, and from her manners and cultivation she would have been though a European.

In fact, Asian races tend to be treated with a degree of contempt in the novel. Papuans are described as the lowest grade of humanity.

On the whole, though, the book is meant to be read as an adventure story. Like most of Verne’s writing, it involves an incredible journey. Verne’s narrative marvels at the power and efficiency of modern transportation; an instrument of progress and civilisation.

Fogg’s assertion that the world has grown smaller is coupled with a belief that the world in knowable. Knowledge is therefore another factor in the civilising power of the modern machine, reflected in various narratorial asides which inform the reader of the history of key places in the novel, usually in the context of their relationship with Britain. Britain, in the novel, is therefore the alpha and omega of the civilised world. Its trade, its wealth, its character, customs and morality are its touchstone.

Inevitably, Verne’s novel is not just an adventure story or a story about technology and progress. It is political. Yet for its 19th Century English audience its ideological assumptions may well have been assumed; transparent in their apparent conventionality. I found this aspect of the novel to be an interesting window into 19th Century thinking. The adventure is still remarkable too, given the conditions under which it is taken, which no doubt is why it still captures the imagination and encourages modern emulators like Palin. But what is left behind, for those who like this sort of thing, is characterisation. Verne’s characters are somewhat one dimensional. Phileas Fogg has of a transformation at the end of the novel when he faces disaster, but his impassible English spirit makes that change hard to detect, if it is ever really there, in course of the novel. Maybe that shouldn’t be a consideration in a book like this. It’s meant to be light; an entertainment. And the book does that well enough, even though the narrative is fairly simple – entirely linear - and the style matter-of-fact.

Related Book Reviewd on this Website

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter