I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important in the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.

President John F Kennedy, address to Congress on 25 May 1961

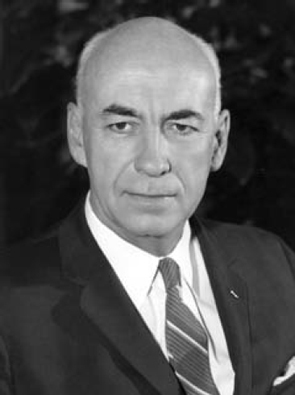

When Kennedy won the November 1960 U.S. election he was the youngest person to be elected President. He started his term in January 1961 with a confidence that he would head an administration which would achieve great things, both domestically and in foreign affairs. After all, he was young, he was charismatic and he had an optimistic vision on his side. The man he succeeded, Eisenhower, was at that time the oldest president. Kennedy was a symbol of a new era, a man who could move the country forward after years of stagnation.

But by May 1961 the gloss had started to wear off his presidency. The Bay of Pigs incident was internationally embarrassing. So to was the Soviet success in space. The Soviets were the first to orbit the Earth. They were the first to send instruments into space. And worst of all, on 12 April 1961, Yuri Gagarin became the first human to fly in space.

These embarrassments followed a much earlier embarrassment: the U.S. Vanguard rocket had failed spectacularly in a live broadcast, exploding a few seconds after launch. Eisenhower had ordered Vanguard to be launched earlier than planned in response to the Soviet success with their Sputnik satellite project. Vanguard's failure became an international joke, with the story appearing in newspapers under names such as Flopnik, Stayputnik, Kaputnik, and Dudnik. A Soviet delegate to the United Nations offered his U.S. counterpart a share in the Soviet foreign aid program which provided technical assistance to backwards nations.

Eisenhower responded by forming NASA in 1958 to control all U.S. non-military space activities. He also gave Wernher Von Braun's team approval to start work on rocket designs they had been proposing for many years.

Kennedy had made use of the 1950s Soviet successes in space in his election campaign, claiming that under Eisenhower and the Republicans, the U.S. had fallen behind the Soviet Union in the Cold War.

Now it was Kennedy's turn to be embarrassed. Despite the success of Project Mercury which launched Alan Shepherd into space on 5 May 1961, the U.S. and Kennedy had to acknowledge that the Soviets were beating them at every turn. Kennedy needed something that he could be sure that the U.S. would be able to achieve first.

Apart from Project Mercury, NASA had already started considering the possibility of a manned flight to the moon, and had formed the small Space Task Group in 1958. Headed by Robert Gilruth, this group started considering how a man could be sent to the moon, and had some initial plans for the spacecraft. Eisenhower was ambivalent to manned spaceflight, and considered terminating the project. Kennedy, first as a Senator, and then earlier in his presidency, was also opposed to the space program. Johnson however, first as Senate leader and then as Vice President, was fascinated by the idea of manned space exploration and saved the program from being disbanded.

So when Kennedy, desperate to restore some of the gloss from the start of his presidency and needing a project where he could be sure the U.S. could finally beat the Soviets, NASA had enough plans in place to offer up Project Apollo for sending a man to the moon. What had been once thought of as a prohibitively expensive project which would never be funded became something which could restore U.S. prestige. Kennedy addressed Congress on 25 May 1961 in a speech titled Special message to the Congress on urgent National needs

. Congress approved the funding, and the Space Task Group suddenly expanded significantly, and set to work to transform their nebulous plans into reality by the deadline imposed by Kennedy.

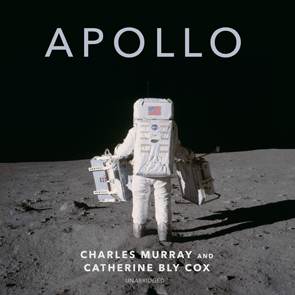

This book, Apollo, provides a detailed study on just how they did that. It looks at the entire Apollo project, and some of the prior history of the Langley Research Centre, Von Braun's team at Marshall, and the Mercury and Gemini projects. It focusses on the engineers and administrators who took a seemingly impossible task and made it happen. The astronauts are mentioned occasionally, but are always tangential to the story being told. Important yes, but not the focus of the story being told here.

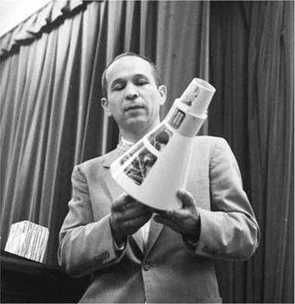

The level of detail in this book is incredible, with the authors having access to huge amounts of documentation covering the duration of the program. They also interviewed many of the people involved, and got their direct memories on the other players and on key events. Apollo covers the political background to the project, the early days at Langley and NACA (the Langley based organisation which became NASA) and the work of Von Braun's group at what became the Marshall Space Flight Centre in developing the Redstone and the Saturn rockets.

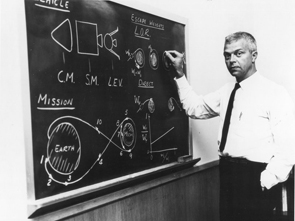

It gives a detailed coverage of the conflicting flight engineering concepts of direct ascent, Earth orbit rendezvous(EOV) and lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) (the concept which was eventually used).

The book also details the establishment of the John F Kennedy Flight Centre (originally called the Launch Operations Centre) at Merritt Island, near Cape Canaveral, Florida (the primary launch centre for human space flights) and the Lyndon B Johnson Space Centre (originally called the Manned Spacecraft Centre) in Houston, Texas (where all astronaut training, research and flight control were conducted).

The book discusses many of the problems encountered over the course of Project Apollo, from major arguments such as EOV vs LOV, and more esoteric problems such as the combustion instability in the F-1 engines used in the first stage of the Saturn V rockets.

A major section of the book concerns the Mission Control Centre and the flight controllers who worked in it. Flight control was headed by Chris Kraft, one of the original members of the small Space Task Group. He was given responsibility at that time for developing a mission plan, a seemingly simple task:

Chris, you come up with a basic mission plan. You know, the bottom-line stuff on how we fly a man from a launch pad into space and back again. It would be good if you kept him alive

- Chuck Matthews, head of Flight Operations Division

Starting completely from scratch, Kraft developed a vast plan which ultimately led to the concept of a mission control centre. He became the first Flight Director for the Mercury program, before moving up to Head of Mission Operations for the Gemini project and to Head of Flight Operations by the time Apollo 7 flew. The book provides a detailed coverage of the formation of the flight control group for Mercury, and the rigorous training each member had to undergo to be ready for any which may come up on a mission.

The actual Apollo missions in general receive far less coverage, with the focus instead being on the launches (and the many problems which could go wrong at launch), and the mission control during the flights. The horrific fire during a test of Apollo 1, the electronic problems caused by the lightning strike on Apollo 12 and the disastrous oxygen tank explosion on Apollo 13 are covered in much more detail than the successes of Apollo 8 and Apollo 11 (Apollo 9, Apollo 10 and Apollo 14 through 16 don't get a mention and Apollo 17 only gets a brief mention as the end of the Apollo missions).

Although politics do get an occasional mention, it is mainly in relation to the funding of the space program. There is scarcely a mention of any of the other major events of the 1960s, such as the civil rights movement. However, there are some reminiscences recorded from various engineers about how isolated they were from the world in general while their time was so intently focussed on the various problems with Apollo. One engineer recorded being so focussed on the launch preparations for Apollo 6 on 4 April 1968, he had no idea of an historic event which happened on the same day – nor had he been paying any attention to current affairs to understand the significance of it if he had heard – that Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated.

This was a fascinating book and one which I would absolutely recommend to anyone interested in the Apollo program and space flight in general.

Other Related Books Reviewed on this Website:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!