When Charles Dickens was growing up there was an unusual number of white Christmases in England. Dicken’s first nine Christmases were white, while there have only been seven white Christmases in London since 1900. In a little article I stumbled upon, Alastair Jamieson suggests that Dickens’s depictions of Christmas were nostalgic for his childhood, which have in turn introduced a false kind of nostalgia for snow laden trees in our culture, forever after affecting Christmas imagery. It’s an interesting thought, given that Art yearns for this kind of ‘real’ winter in Ali Smith’s novel:

What he longs for instead, as he sits at the food-strewn table, in winter, winter itself. He wants the essentiality of winter, not this half-season grey selfsameness. He wants real winter where woods are sheathed in snow, trees emphatic with its white . . .

There is an irony in longing for this false authenticity, but a lot of nationalism and attitudes engendered by the Brexit vote, Smith might argue, are no more than atavistic illusions: national identity; cultural unity.

This is the second in Ali Smith’s planned Seasonal Quartet

; four books that began with Autumn and that will presumably end with Summer. So far, they have focussed on contemporary issues in England through stories based around ordinary people struggling with the historical and moral import of Brexit and the era of post-truth. While Autumn focussed on issues of identity that the Brexit vote raised, Winter is set within the historical context of millions of displaced refugees in Europe, the moral implications of climate science, of militarism, as well as the problem of authenticity in an era of fake news and Donald Trump. Smith achieves a sense of the moment with little details readers may remember: the Grenville fire, Trump’s address to the Boy Scouts’ convention or that strange moment when Sir Nicholas Soames barked like a dog at Tasmina-Ahmed Sheikh in the British parliament.

The story is fairly basic. Arthur, or Art, plans to visit his mother, Sophia, for Christmas. However, he has just fallen out with his girlfriend, Charlotte, whom he promised his mother she would meet. Art decides to pay Lux, a girl he meets at a bus stop as she reads a menu she cannot afford to make a purchase from, £1000 to accompany him to his mother’s house for the weekend and pretend to be Charlotte. When they find his mother in an emaciated state with no food in the house, he decides to call his aunt, Iris, Sophia’s long estranged sister, for help and supplies of food to get them through Christmas. The potential for conflict and embarrassment is obvious enough, not to mention the issues of authenticity.

While all this seems rather serious, there are some genuinely funny scenes in this novel – at one point I involuntarily laughed out loud (something I normally don’t do) – and at other times I was left to admire the artistry of Smith’s narrative that blends the worlds of art, literature and politics. The issue of authenticity, for instance, which goes to the heart of this novel, is handled with a lot of humour. Art’s girlfriend, Charlotte, takes over his twitter account once he leaves for the weekend and pretends to be him by making posts to his nature blog. Art, who is mortified by the false claims and inaccuracies being posted in his name – and bothered by people after Charlotte publishes his phone number – prefers to turn off his phone rather than face the unfolding travesty. Charolotte, against reason, is gaining followers with her ludicrous announcements. This is the age of fake-news and click bait, after all. But Art cannot escape the busloads of tourists who turn up at his mother’s house, determined to spot a Canadian Warbler, a bird never-before-seen in England, purported to have survived the trans-Atlantic flight on no less an authority than his own twitter account.

For Art the issue of authenticity goes to the heart of his very identity. His job is chasing down copyright infringements on the Internet while his name suggests artifice, which is borne out by his own fictionalised approach to his nature blog; he prefers not to meddle with nature but make it up. And there is also the issue of his upbringing which he struggles to remember, as both his aunt and mother lay claim to raising him. His very parentage, the identity of his father, is something of a mystery, too. Meanwhile, Lux, the poor immigrant girl he pays to accompany him home, knows Shakespeare better than any of them, even if she doesn’t always understand the idiosyncrasies of the English language. Lux recounts Cymbeline to Art’s family, but they almost fail to recognise it, leaving Art to wonder how an immigrant can know more than him about his cultural heritage. Smith is clever in the way she suggests positions rather than states them. What makes a person English? Who is authentically English?

Lux’s story is just one route into the thorny question of national identity and issues of immigration with which the novel grapples. Iris, a long-time protester against all manner of things (plastic bags, nuclear weapons, pesticides…), comes into conflict with Sophia who lives alone in a rambling mansion but has no empathy for the millions of displaced people in Europe without a home. But for people like Lux, impoverished and desperate because of the new British immigration laws that prevent her from gaining proper employment – she does not even know whether she will be allowed to stay in the country – the issue is not an academic or moral question, but a reality of life.

Like its predecessor, Winter makes allusions to Dickens. Smith loosely bases the narrative upon Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. Sophia is ‘visited’ by ‘ghost’ in a sense. The strange incident of the floater in her eye at the beginning of the story she mistakes as a disembodied head, her sister’s reappearance or Lux’s presence all force her mind back to the past or the issues of her family and her country. We see into Sophia’s past when she first meets Art’s father, we see the characters struggle over their own relationships and their country’s place in the world in the present, and for Christmas future we see Art read A Christmas Carol to his future child. But Sophia’s is a mind determined to withdraw from the modern world, to escape the atrocities and refugees and blood that her floater forces upon her mind and live in a perfected fantasy of Dickens’s novel without the reality of Tiny Tim. Sophia’s is an amoral world that the conventional Christmas tropes, some possibly invented by Dickens, could easily elide.

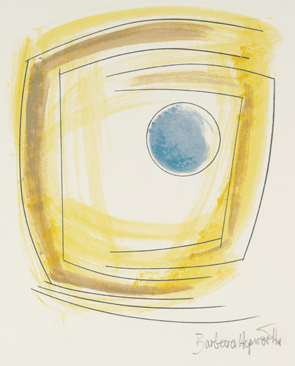

I think this is where Smith shows her craft. Both Autumn and Winter focus on an artist as a metaphor within the narrative. In this case it is Barbara Hepworth whom Sophia says lived nearby, and it is Hepworth’s presence in the narrative that allows Smith to articulate the problem of empathy in the modern world. Theresa May, as the epigraph to the novel shows, derided the idea of England as a part of Europe (“…if you believe you are a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere”) and by extension the responsibility of Britain to the plight of others. But Godfrey, Art’s father, advocates the importance of a universal language

he believes Hepworth strove for in her art. It’s the same insight Lux has through Shakespeare’s Cymbeline:

. . .it’s like the people in the play are living in the same world but separated from each other, like their worlds have somehow become disjointed or broken off each other’s worlds. But if they could just step out of themselves, or just hear and see what’s happening right next to their ears and eyes, they’d see it’s the same play their all in, the same world, that they’re all part of the same story.

The novel is deceptively short. It has many contemporary allusions, allusions to art and literature, and is layered in its narrative construction. The man Iris meets in her flat, for instance, seems analogous to the man Sophia meets on the street. Iris’s intruder is threatening, Sophia’s gentleman romantic. At any point in the story you begin to see layering, allusions and parallels. I wondered at the import of these different meetings and whether this said something about patriarchal power. One sister challenges it and is assaulted, the other is submissive and is wooed. There is so much to take in with Smith’s simple narrative that you can be some way into a scene before you realise that what was personal and domestic has become political, and visa versa. Smith is an exemplary writer, and this is a sophisticated, dramatic and sometimes funny account of our times.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!