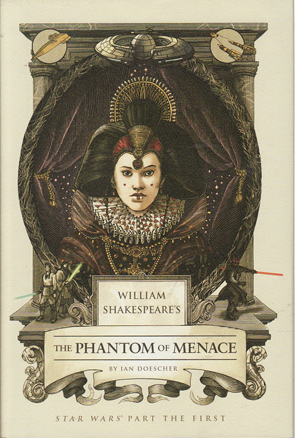

Ian Doescher is the author of William Shakespeare’s The Phantom of Menace, but he does not hold copyright over the work. Copyright belongs to Lucasfilm Ltd which is now owned by the Disney Corporation. That’s probably not news to anyone about to read this review, but the significance lies in the fact that there can be no authorised productions of Doescher’s versions of Star Wars or audio book productions while ever Lucasfilm maintains its present position. Upon finishing my reading of the play, it seemed to me the obvious thing to do: to look to see whether there had been productions of any of the books. There hasn’t, at least nothing authorised. This is in contrast to Stephen Briggs’s play adaptations of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series, which I know have often been produced by schools and amateur theatre companies. In fact, I saw an amateur theatre production of The Truth a couple of years ago. The original novel was better.

My interest in this lies in the fact that Doescher was authorised to write these plays which are meant only to be read. Shakespeare’s plays are performed frequently all over the world, but for many, their connection with the plays comes via state-imposed school curriculums that alienate many students just as much as they inspire others; read in classrooms to be examined rather than viewed live in a theatre to be enjoyed. With Doescher’s adaptations, however, it seems to me that Disney’s Lucasfilm is balancing its interests between a desire to extend Star Wars merchandising and its brand into another market, but at the same time maintain control over the representation of their intellectual property.

I can make two points to illustrate what I mean. First, Doescher’s text is gently satirical and relies heavily on fans’ knowledge of the film to understand and appreciate its humour. A knowledge of Shakespeare would add to the appreciation of the text but it is not essential. Everyone knows, Shakespeare, right? Even if it’s just an uncomfortable memory of those awkward pronouns (that actually make more sense than modern pronouns, once you are used to them). But an intimacy with the film brings rewards. For instance, Jar Jar Binks, whom Doescher acknowledges as perhaps the most hotly debated character in cinematic history

(read hated

by those not beholden to the Disney corporation) is given a new dimension by Doescher. Instead of the irritating fool whom George Lucas meant to be funny and ingratiating, Doescher suggests Jar Jar is a sophisticated Machiavellian with benign intentions to unite the Gungans with Queen Armidala’s Nubians. To achieve his aims, he adopts the demeanour of a fool so as to slip under the prejudicial radar of the Jedi knights and Nubians. Given that the text had to be approved by Lucasfilm, this reimagining makes the best out of an unloved character in one of the most unloved Star Wars films. In other words, Lucasfilm approved of this new Jar Jar, reimagined in the stone edifice of unchanging text.

My second thought was that if Lucasfilm approved productions of the plays it would cede, to some extent, the control that unchanging text gives them over the representation of its intellectual property. It is not enough to say that the text is the text, now, as though its representation on stage is an unproblematic given, since Shakespeare has been reinterpreted and reimagined for four hundred years. I doubt that deliberately malicious representations of the plays would be allowed – re-interpretations dedicated to deprecating the Star Wars brand – but to some extent, it would be unavoidable, even in well-intentioned productions. My mind wandered to this while reading the pod race scene. Doescher, himself, mentions this scene at the end of this book, since its fast-paced action over a vast landscape is impossible to represent on stage. Of course, the solution was obvious: do as Shakespeare did. In scenes involving the outcomes of battles, such as the battle against Cyprus at the beginning of Othello, or Mark Antony’s sea battle in Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare resorted to having the battle narrated by witnesses who return to the stage for the sake of the waiting protagonists. Doescher employs this same technique, with Padmé and Jar Jar running backwards and forwards to report what they see, along with the two-headed Fode who commentates the race and appears to see all. But added to all this is the detail of the pod racers zooming across the stage occasionally as they complete their laps, like dramatic punctuations for the audience. This is what got me thinking about intellectual property. I remember reading an article about the strict requirements the Apple corporation has about how its brand is positioned: where its stores can be located, where is billboards can be seen and the amount of light required to light the products and its signage. Big businesses care about their image, and I wondered at the image cast by a would-be local production as they ferried their Anakins and Sebulbas across the stage in what might turn out to be the equivalent of wheel-less billy carts to represent the pod racers. For any who don’t know, a wheel-less billy cart is usually a cardboard box decorated and held around the waste by small children in primary schools as they race about the oval. At least, that is what it is where I come from. And if you think there would be an element of farce connected to this staging, imagine the irony of that for a set of films that were often on the cutting edge of special effects development, and thereby the unintended diminishment of the brand.

That, at least, is what I suspect would be part of the reasoning behind a ban on the production of Doescher’s versions.

I also suspect it is a limiting factor in the range of humour Doescher could attempt. Quirk Publishers has also published other popular books like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, which was not restricted by intellectual property considerations, given the age of the original source material. I felt there was a freer hand at work when reading that book. Doescher’s adaptation seems more respectful of its source material. There are slight changes, like those to Jar Jar’s character, but on the whole the story moves along the same lines as the movie, even down to little details, like Jar Jar accidentally taking out Federation robots on the battle field as he trips around a mangled robot with its blaster still active. Doescher turns this around, with Jar Jar quite knowingly doing what he does, as this version of Jar Jar would. But a lot of the text merely trundles out the plot with few surprises in a more formalised English reminiscent of Shakespeare.

At times, this is leavened by little asides or references to Shakespeare’s own texts. R2-D2 charmingly breaks out of character to talk to the audience in English, and Anakin, when he first meets Padme, breaks into an impassioned aside – “O, she doth teach the torches to burn bright!” - in a Romeo-like moment that makes comparison not with Padmé and stars but with the brightness of his own home planet, Tatooine. Darth Maul is also given an appropriate soliloquy which echoes the bastard Edmund’s speech from King Lear:

- Deprive me for that I am some twelve deeds

- Lag of some honor? Why Sith? Wherefore base?

- The path of shadows is my chosen way,

- And who shall call me

villain

for the choice?

And I admit, it is kind of funny to have well-known characters speaking so formally in the middle of heated battles, like the final battle between Qui-Gon and Darth Maul. Most entertaining, I thought, is Doescher’s treatment of Yoda’s speech. Yoda, famous for his inverted syntax in the films, would not stand out so well in this Shakespearean version, given that it is a common characteristic of Shakespeare’s writing. Doescher solves the problem. Instead of speaking in iambic pentameter, Yoda speaks in haiku!

However, I still felt this book should have been funnier and less respectful. I have a memory of reading Bored of the Rings when I was at school, when Lord of the Rings was probably the best book I had ever read, and loving it: even though National Lampoon’s take on the fantasy classic was rude and disrespectful. If there is anything to be said about this book is that Lucasfilm maintained too much creative oversight.

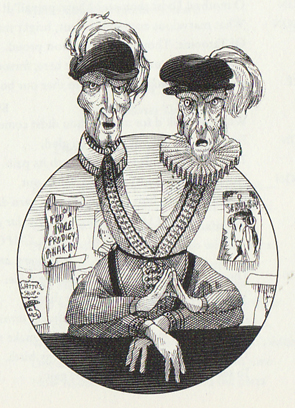

But I think there is also another consideration here. There are many Star Wars fans and these books still have a quirky gimmick that will prove irresistible for many. The current publications are quality productions. They are hardback with dust jackets and have great line illustrations throughout, often melding the Star Wars universe with that of the Bard’s. So far, I admit, I have bought the first seven books, and I discovered this afternoon as I checked Ian Doescher’s website that the eighth, William Shakespeare’s Jedi the Last, has been published. Despite whatever misgivings I had about this one, I will still buy it. I’m a completionist, so there will eventually be nine reviews of Doescher’s books on this website, no doubt. I think this book could have been better, but it will probably please a lot of fans. I’m hoping for a little more, however, as I get to the other books.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!